China and the Korean Peninsula Gordon G. Chang Forbes.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Activities

faculty activities Bruce Ackerman • “Development lawyering, Between Equality and publications Subordination: The Politics of legal Knowledge in • Goodbye Montesquieu, in S. Rose-Ackerman & Global North-South Academic Exchange,” Yale law P. Lindseth eds., Comparative Administrative Law 128 School, Mar. 24, 2012 (2011) publications • Nixon In Iran?, Huffington Post, Mar. 19, 2012 • Developing Citizenship, 9 Issues in Legal Scholarship • The Legal Case Against Attacking Iran, L.A. Times, 1 (oct. 2011) (online) Mar. 5, 2012 Bruce Ackerman • Reconstructing Citizenship for the Twenty First Century, Ian Ayres an Interview with Bruce Ackerman, La Vie des Idees, lectures and addresses Mar. 5, 2012 • “The Rise of Data Driven Decision Making,” IBM Tokyo, • How Congress Can Overrule Citizens United Nov. 8 (with I. Ayres), Huffington Post, Feb. 9, 2012 • “how to Regulate opt out: An Economic Theory of • Recess Appointments: Release the Legal Advice, Altering Rules” (NYU, Yale, University of Connecticut Wall St. J., Jan. 11, 2012 law Schools) • Washington Standoff, L.A. Times, Jan. 6, 2012 • Information Escrows, Berkeley and Yale • A Christmas Present for the Pentagon, Slate, Dec. 28 • 9 Randomized Tests to Improve Tax Compliance, hMRC Muneer I. Ahmad 2011 Debt Management, london • A United States of Europe?, L.A. Times, Dec. 14, 2011 publications • The Law School Experience [letter], N.Y. Times, Dec. 5, • Anti-Incentives: The Power of Resisted Temptation, Eur. 2011 Fin. Rev. 40 (Feb.-Mar. 2012) • Supreme Court’s Obamacare Ruling Will Politicize • Randomizing Law, 159 U. Pa. L. Rev. 929 (2011) (with Judicial Process, Daily Beast, Nov. 15, 2011 M. Abramowicz & Y. listokin) • Don’t Tax the Rich. -

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: the Chibok Girls (60

TV NATIONAL HONOREES 60 Minutes: The Chibok Girls (60 Minutes) Clarissa Ward (CNN International) CBS News CNN International News Magazine Reporter/Correspondent Abby McEnany (Work in Progress) Danai Gurira (The Walking Dead) SHOWTIME AMC Actress in a Breakthrough Role Actress in a Leading Role - Drama Alex Duda (The Kelly Clarkson Show) Fiona Shaw (Killing Eve) NBCUniversal BBC AMERICA Showrunner – Talk Show Actress in a Supporting Role - Drama Am I Next? Trans and Targeted Francesca Gregorini (Killing Eve) ABC NEWS Nightline BBC AMERICA Hard News Feature Director - Scripted Angela Kang (The Walking Dead) Gender Discrimination in the FBI AMC NBC News Investigative Unit Showrunner- Scripted Interview Feature Better Things Grey's Anatomy FX Networks ABC Studios Comedy Drama- Grand Award BookTube Izzie Pick Ibarra (THE MASKED SINGER) YouTube Originals FOX Broadcasting Company Non-Fiction Entertainment Showrunner - Unscripted Caroline Waterlow (Qualified) Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) ESPN Films FX Networks Producer- Documentary /Unscripted / Non- Actress in a Leading Role - Made for TV Movie Fiction or Limited Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) Mission Unstoppable Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) Produced by Litton Entertainment Actress in a Leading Role - Comedy or Musical Family Series Catherine Reitman (Workin' Moms) MSNBC 2019 Democratic Debate (Atlanta) Wolf + Rabbit Entertainment (CBC/Netflix) MSNBC Director - Comedy Special or Variety - Breakthrough Naomi Watts (The Loudest Voice) Sharyn Alfonsi (60 Minutes) SHOWTIME -

CURRICULUM VITAE Bruce E

CURRICULUM VITAE Bruce E. Bechtol Jr. Ph.D. Angelo State University ASU Station #10896 San Angelo, Texas 76909-0896 Cell Phone (540) 538-4273 Work Phone (325) 486-6792 Home Email Address: [email protected] Work Email Address: [email protected] Academic Background: Ph.D., National Security Studies, The Union Institute, Cincinnati, Ohio, 2000. Master of Arts in International Affairs, Catholic University, Washington DC, 1996. Master of Military Studies (Distinguished Graduate), U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Quantico, Virginia, 2001. Bachelor of Science in Liberal Studies, Excelsior College, Albany, NY, 1994. Current Position: 2015-Present Professor of Political Science, Angelo State University, San Angelo, TX. Previous Teaching Experience: 2010-2015 Associate Professor of Political Science, Angelo State University, San Angelo, TX. 2007-2010 Professor of International Relations, Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA. 2006-2007 Visiting Adjunct Professor (Non-Resident), Graduate School of International Studies, Korea University, Seoul, Korea. 2005-2007 Associate Professor of International Relations Marine Corps Command and Staff College, Marine Corps University, Quantico, VA. 2005-2009 Adjunct Professor of Diplomacy (Online), Norwich University, Northfield, VT. 2003-2005 Assistant Professor of National Security Studies, Air Command and Staff College, United States Air University, Montgomery, AL. 2002-2009 Adjunct Professor of Liberal Studies (Online), Excelsior College, Albany, NY. 2001-2003 Adjunct Professor of National Security Studies and International Relations, American Military University, Manassas, VA. 1998-2003 Thesis Advisor, Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence Program, Joint Military Intelligence College, Washington DC. 1994-1997 Senior Instructor, Intelligence Systems, Marine Corps Systems Command, Quantico, VA. -

Assumed Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases1

Assumed Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases1 CONTRACT DESCRIPTION COUNTERPARTY DEBTOR CURE AMOUNT RADIO NETWORKS, PROGRAMMING CONTRACT 12 STOPS INC $0.00 LLC CITADEL COMMUNICATIONS 1VELOCITY, INC. BROADCASTING $0.00 CONTRACT COMPANY OTHER CITADEL 201 ST CHARLES PLACE CONTRACT START DATE: BROADCASTING $48.89 LLC 08/01/2006 COMPANY REAL PROPERTY LEASE CITADEL 201 ST CHARLES PLACE CONTRACT START DATE: BROADCASTING SEE ABOVE LLC 09/01/2003 COMPANY REAL PROPERTY LEASE CITADEL 201 ST CHARLES PLACE CONTRACT START DATE: BROADCASTING SEE ABOVE LLC 08/01/2006 COMPANY TOWER/TRANSMITTER CITADEL LEASE 201 ST CHARLES PLACE BROADCASTING SEE ABOVE CONTRACT START DATE: LLC COMPANY 01/01/2003 TOWER/TRANSMITTER LEASE ALPHABET 233 BROADCAST LLC $0.00 CONTRACT START DATE: ACQUISITION CORP. 10/01/2003 REAL PROPERTY LEASE / 260-261 MADISON AVENUE RADIO NETWORKS, SUBLEASE DATED 11/7/2008 $0.00 LLC LLC AS AMENDED 4/16/2010 CITADEL REAL PROPERTY LEASE / 2-L BROADCASTING $0.00 SUBLEASE COMPANY REAL PROPERTY LEASE CITADEL CONTRACT START DATE: 59 61 COURT ST LLC BROADCASTING $0.00 07/01/2007 COMPANY REAL PROPERTY LEASE CITADEL CONTRACT START DATE: 60 MONROE CENTER LLC BROADCASTING $21,767.21 08/01/2004 COMPANY 1 Neither the exclusion nor inclusion of any contract or lease on this list of assumed Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases, nor anything contained in the Plan, shall constitute an admission by the Debtors that any such contract or lease is in fact an Executory Contract or Unexpired Lease capable of assumption or that any Reorganized Debtor(s) has any liability thereunder. Further, the Debtors expressly reserve the right to (i) remove any Executory Contract or Unexpired Lease from this list before the Effective Date; (ii) remove any Executory Contract or Unexpired Lease from this list and reject such Executory Contract or Unexpired Lease before entry of the Confirmation Order; or (iii) contest any claim (or claim amount) asserted in connection with assumption of any Executory Contract or Unexpired Lease. -

How to Switch Programs on the XDS Pro Using Serial Commands Every

How to switch programs on the XDS Pro using Serial Commands Every Program transmitted via the XDS satellite system is associated with a Program ID that identifies the program to the receiver. Individual programs may be selected to the receiver’s output ports by issuing serial ID commands via the M&C (Console) Port on the back of the receiver, thereby changing the program that the receiver is decoding. If a program is selected for decoding using this method that is NOT part of the station’s list of authorized programming, it will NOT be decoded. Only programs authorized for the station that the receiver is assigned to can be decoded. Whenever possible, always use the XDS Port Scheduler as your main method of taking a program to ensure you receive the proper content. You can command the receiver as follows: 1) Start a terminal session (using HyperTerminal or equivalent) by connecting to the receiver’s M&C (Console) Port. The default settings for this Port are 115200, 8, None, 1. 2) Hit Enter. You should see a “Hudson” prompt. 3) Log in by by typing LOGIN(space)TECH(space)(PASSWORD) (Use your Affiliate NMS (myxdsreceiver.westwoodone.com) password OR you can use the receiver’s daily password (Setup > Serial # > PWD). 4) Login confirmation will be displayed (‘You are logged in as TECH’) Once you are logged in, the command to steer a Port on the receiver to a specific program PID is: PORT(space)LIVE,(Port),ID Examples: PORT LIVE,A,99 – This command will set Port A to Program ID 99 (Mark Levin) PORT LIVE,B,1196 – This command will set Port B to Program ID 1196 (CBS Sports - Tiki and Tierney) Please refer to the PID table listed below for the Program ID assignments for each program available on the Westwood One XDS receiver. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, As Amended

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 03/30/2014 11:38:52 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28,2014 u.s. Department of justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending February 28,2014 (Insert date) I-REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Beckermari , 5877 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant One University Plaza Suite 500 HackensackNJ 07601 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No • (2) Citizenship Yes • No • (3) Occupation . Yes • No • (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes • No fx] (2) Ownership or control Yes O No IE1 (3) Branch offices Yes • No 0 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3,4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No H If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No • If no, please attach the required amendment , 1 TKe Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a tree copy of the charter, articles of mcorporatoon, association, and by laws ot a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Andrew B. Newberg Page 1 Curriculum Vitae

Andrew B. Newberg Page 1 Curriculum Vitae Andrew B. Newberg, M.D. Education: 8/84-5/88 B.A. Haverford College Haverford, PA 19034 8/88-5/93 M.D. University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine Philadelphia, PA 19104 Postgraduate Training and Fellowship Appointments: 6/93-6/94 Internship in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/94-6/96 Residency in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/96-6/97 Chief Resident, in Internal Medicine, Graduate Hospital, Philadelphia, PA 19134 7/97-6/98 Fellow, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 7/97-1/98 Chief Fellow, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104 Faculty Appointments: 7/94-6/97 Assistant Instructor, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 7/98-11/99 Clinical Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 7/97-7/99 Instructor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 12/99-6/06 Assistant Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 6/03-10/10 Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 10/05-10/10 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies, University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences 7/06-10/10 Associate Professor of Radiology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine 10/10-present Professor of Emergency Medicine, Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital 10/10-present Professor of Radiology, Thomas Jefferson University and Hospital 7/15-present Adjunct Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Pennsylvania, School of Arts and Sciences Hospital and Administrative Appointments: Andrew B. -

2014 Hoover Journalist Program

MEMBERS OF THE MEDIA WHO PARTICIPATED IN HOOVER’S JOURNALIST PROGRAMS – 2014 NAME AFFILIATION Spencer Ackerman The Guardian Binyamin Appelbaum New York Times Ryan Avent The Economist Kate Bachelder Wall Street Journal Fred Barnes Weekly Standard John Batchelor John Batchelor Show Steve Beckner Market News International John Berry The International Economy Magazine Tom Bevan Real Clear Politics Patrick Brennan National Review Carl Cannon Real Clear Politics Lou Cannon Real Clear Politics Steve Chapman Chicago Tribune Rob Cox Reuters Michael Crowley Time Magazine Pedro da Costa Wall Street Journal Howard Dickman Wall Street Journal Ken Dilanian Los Angeles Times Geoff Dyer Financial Times Michelle Fields PJ Media Allysia Finley Wall Street Journal Bill Gertz Washington Free Beacon/ Washington Times Bobby Ghosh Time Magazine Robin Harding Financial Times Kathleen Hays Bloomberg Radio Fred Hiatt Washington Post Jon Hilsenrath Wall Street Journal Mark Hosenball Reuters Blake Hounshell Politico Charles Hurt Drudge Report Greg Ip The Economist Neil Irwin New York Times Hoover Institution Stanford University 434 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-6010 T 650-723-1754 The Johnson Center 1399 New York Avenue NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20005 T 202-760-3200 Hoover.org Michael Isikoff NBC News Aki Ito Bloomberg Carrie Johnson National Public Radio Terry Jones Investor’s Business Daily Brianna Keilar CNN Mary Kissel Wall Street Journal Live Larry Kudlow Larry Kudlow Show Elise Labott CNN Lars Larson Lars Larson Show Mark Laswell Wall Street Journal -

ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994

Update on the 141 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994 24th Annual Robert Novak Journalism Fellowship Awards Dinner May 10, 2017 2017 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP AWARD WINNERS HELEN R. ANDREWS | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Eminent Boomers: The Worst Generation from Birth to Decadence” Helen earned a degree in religious studies from Yale University, where she served as speaker of the Yale Political Union. Currently a freelance writer and commentator, she served for three years as a policy analyst for the Centre for Independent Studies, a leading conservative think tank in suburban Sydney, Australia. Previously, she was an associate editor at National Review. Her work has appeared in First Things, Claremont Review of Books, The American Spectator, The Weekly Standard and others. MADISON E. ISZLER | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “What’s Killing Middle-Aged White Women—and What it Means for Society” Madison holds a master’s degree, cum laude, in political philosophy and economics from The King’s College. Currently, she is an Intercollegiate Studies Institute Reporting Fellow. She has interned for USA Today and the National Association of Scholars and was a reporter for the New York Post. Her work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the Raleigh News & Observer, Charlotte Observer, New York Post and Miami Herald. Originally from Florida, she resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. RYAN LOVELACE | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Hiding in Plain Sight: Criminal Illegal Immigration in America” An Illinois native, Ryan attended and played football for the University of Wyoming. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from Butler University. -

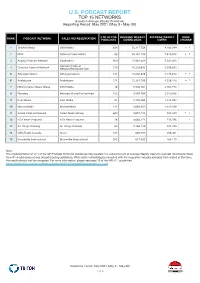

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

Inside This Issue

News Serving DX’ers since 1933 Volume 80, No. 7● November 12, 2012 ● (ISSN 0737-1639) Inside this issue . 2 … AM Switch 9 … Domestic DX Digest East 19 … Pro Sports Networks (NBA) 4 … Space Weather Forecast 16 ... Musings of the Members 23 … Tower Calendar/e-QSLs 5 … Domestic DX Digest 17 … DX Tool Box 24 … The Fine Print From the Publisher: No IDXD this week, as by frequency, including call letters, state, city, Bruce has been on DXpedition for the last few day/night power, slogans, schedule in days – expect a big IDXD next issue. UTC/GMT, formats, networks and notes. The Eleven stations crossed off our DDXD call letter index gives call, frequency, city and unreported list this week: WFCM‐710, KBBW‐ state. The city index (listed by state, then city) 1010, WNES‐1050, WFKN‐1220, KWNO‐1230, includes frequency, call and day/night power. KGRO‐1230, WQKR‐1270, WNBS‐1340, WJZM‐ The transmitter site index (listed by state, then 1400, WTKM‐1540, WDBL‐1590, plus new CBEF‐ city) tabulates the latitude and longitude of 1550. There are 609 left – can you report one? transmitter sites. This is an indispensable reference for anyone who hears Mexican radio Membership Report stations. Size is 8 1/2ʺ x 11ʺ. Renewing Members – Thanks for the Prices: IRCA/NRC members – $9.50 continued support of Frank Aden, Jr.; John (US/Canada/sea mail), $11.50 (México), $12.50 Callarman; David Cox; George B. Holland Jr.; (rest of the world). Non‐IRCA/NRC members – David Larrabee; Kurt Nelson; Ira Elbert New III; add $2.00.