Out-Migration, In-Migration and the Strait Region of Nova Scotia, 2001-2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement to the Public Accounts 7

SUPPLEMENT TO THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS 7 Agriculture and Marketing — (Continued) Trueman, Brian C........................... 1,115 95 Accounts Payable Adjustment .... 28,597 71 Walsh, Frederick A........................... 2,160 55 Less Recoveries ................................ 1^19 95 Wilson, Harold G.............................. 1,782 96 Accounts under $1,000 ................... 27,953 75 $ 283,673 32 Dykv.land Rehabilitation : Advocate Marsh Body ...................$ 1,137 25 Accounts under $1,000 ......... .. 2,632 64 Grand Prc Marsh Body ................. 10,876 17 Accounts Payable Adjustment ..... 1,256 54 Minudic Marsh Body .................... 2,329 85 Less Recoveries ........................... 3,010 70 Truro Dykcland Park Marsh Body 1,136 75 Wellington Marsh Body ............ 1,879 50 $ 18.238 00 Cumin to Societies and Organizations ; Agricultural Economic Research N. S. Mink Breeder’s Association 1,000 00 Council of Canada ....................$ 2,500 00 N. S. Poultry Council .................... 1,000 00 Annapolis Co. Exhibition ......... .... 2,500 00 N. S. Provincial Exhibition ........... 4,000 00 Atlantic Winter Fair ..................... 8,000 00 N. S. Society for Prevention of Canadian Council on 4-H Clubs .... 1,517 00 Cruelty to Animals ................. 1,000 00 Cape Breton Co. Exhibition ......... 2,500 00 Western N. S. Exhibition ........... 2,500 00 Central N. S. Holstein Club .... 1,400 00 Pictou Co. Exhibition .................. 2,500 00 Cumberland Co. Exhibition 2,500 00 Queens Co. Exhibition ................. 1,000 00 Digby Co. Exhibition .................... 1,000 00 Royal Winter Fair .......................... 1,000 00 Eastern N. S. Exhibition .... 2,500 00 Shelburne Co. Exhibition ........... 1,000 00 Halifax Co. Exhibition .... 1,000 00 South Shore Exhibition ............. 4,000 00 Hants Co. Exhibition .................... 4,000 00 Weed Control Act Expenses .......... -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 6 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2011 NOTICE TO CREDITORS, HEIRS AND Lynn Knockwood and Michael Halliday OTHER CLAIMANTS Signatures of Co-Executors In the Matter of the Indian Act, R.S.C., CH. 1-5 and 290 February 9-2011 - (8iss) amendments thereto, and in the Matter of the Estate of Janis Maria Walker, registration number 0300004801 PROVINCE OF NOVA SCOTIA of the Glooscap First Nation, deceased, who died on or DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE about the 19th day of September, 2010, in the Province of Nova Scotia, and who at the time of death had been The Minister of Justice and Attorney General, Ross ordinarily resident of Glooscap. Landry, under the authority vested in him by clause 2(b) of Chapter 23 of the Acts of 1996, the Court and NOTICE is hereby given pursuant to Section 8 of the Administrative Reform Act, Order in Council 2004-84, the Indian Estates Regulations; Assignment of Authority Regulations, and Sections 6 and 7 of Chapter 312 of the Revised Statutes of Nova Scotia, THAT ALL CREDITORS, heirs and other claimants 1989, the Notaries and Commissioners Act, is hereby having demands or claims against the estate of Janis pleased to advise of the following: Maria Walker, who died on or about the 19th day of September, 2010, are required to produce on or before To be revoked as a Commissioner pursuant to the April 6th, 2011 to: Notaries and Commissioners Act: Valerie Britten of Sydney, in the County of Cape Lynn Knockwood Breton (no longer employed with Citizenship and PO Box 346 Immigration Canada). -

Archived Content Contenu Archivé

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. ‘\‘Afak settitIcte lof y Crime and Policing in Digby, 1909 -1990 HV 8159 .N8 M3 p 1990 Occasional Paper Series elc/ c.> e P ent`b ,xeJ I -1-1 _ \ e e e e ,&e- ces e , e 7eb e « çiefee se / \es\\ ,C> ,,,e e e 4:\- eq. -

Annapolis Valley

2021-2022 PRE-DOCTORAL RESIDENCY IN PSYCHOLOGY MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIONS NOVA SCOTIA HEALTH - ANNAPOLIS VALLEY Revised August 2020 2 1. ABOUT ANNAPOLIS VALLEY 3 2. ABOUT NOVA SCOTIA HEALTH AUTHORITY 4 2.1 PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES AND THE DISCIPLINE OF PSYCHOLOGY 4 2.2. Supervising Psychologists 5 3. PRE-DOCTORAL RESIDENCY IN PSYCHOLOGY 7 3.1 PURPOSE 7 3.2 STRUCTURE 7 4. PRIMARY TRACKS AND ROTATIONS 8 4.1. Adult Mental Health Track 8 4.2. Child and Youth Mental Health Track 12 5. SUPERVISION 15 5.1. Standards for Supervision 15 6. EVALUATION 16 7. EMPLOYMENT AND WORK LOAD PROCEDURES 17 7.1. HOSPITAL/CLINIC POLICY 17 7.2. STIPEND AND BENEFITS 17 7.3. OVERTIME POLICY 17 7.4. RESOURCES 17 8. APPLICATION PROCEDURE 18 3 1. ABOUT ANNAPOLIS VALLEY The scenic Annapolis Valley is located within the western peninsula of Nova Scotia and spans approximately 130 km from the picturesque town of Wolfville (home of Acadia University) to the historical and seaside towns of Annapolis Royal and Digby. The pre- doctoral residency program is primarily located in the town of Kentville, a 10- minute drive from Wolfville. Within and around the towns of Wolfville and Kentville can be found a variety of cultural, sporting and recreational activities including professional and community theatre, music, cinema, university sports teams, downhill skiing, golf, and fine and casual dining. Local farms and markets provide exceptional fresh food and quaint seasonal activities (e.g., apple picking, pumpkin patches, corn mazes), while the growing winery, cidery, and microbrewery scenes provide many tasting options for connoisseurs of such adult beverages. -

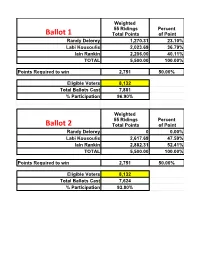

Riding by Riding-Breakdown

Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 1,270.31 23.10% Labi Kousoulis 2,023.69 36.79% Iain Rankin 2,206.00 40.11% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,881 % Participation 96.90% Weighted 55 Ridings Percent Total Points of Point Randy Delorey 0 0.00% Labi Kousoulis 2,617.69 47.59% Iain Rankin 2,882.31 52.41% TOTAL 5,500.00 100.00% Points Required to win 2,751 50.00% Eligible Voters 8,132 Total Ballots Cast 7,624 % Participation 93.80% DISTRICT Candidate Final Votes Points 01 - ANNAPOLIS Randy DELOREY 31 26.5 01 - ANNAPOLIS Labi KOUSOULIS 34 29.06 01 - ANNAPOLIS Iain RANKIN 52 44.44 01 - ANNAPOLIS Total 117 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 02 - ANTIGONISH Randy DELOREY 176 53.01 02 - ANTIGONISH Labi KOUSOULIS 35 10.54 02 - ANTIGONISH Iain RANKIN 121 36.45 02 - ANTIGONISH Total 332 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 03 - ARGYLE Randy DELOREY 37 41.11 03 - ARGYLE Labi KOUSOULIS 24 26.67 03 - ARGYLE Iain RANKIN 29 32.22 03 - ARGYLE Total 90 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Randy DELOREY 92 34.72 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Labi KOUSOULIS 100 37.74 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Iain RANKIN 73 27.55 04 - BEDFORD BASIN Total 265 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Randy DELOREY 116 39.59 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Labi KOUSOULIS 108 36.86 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Iain RANKIN 69 23.55 05 - BEDFORD SOUTH Total 293 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Randy DELOREY 11 12.36 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Labi KOUSOULIS 30 33.71 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Iain RANKIN 48 53.93 06 - CAPE BRETON CENTRE - WHITNEY PIER Total 89 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Randy DELOREY 22 19.47 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Labi KOUSOULIS 32 28.32 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Iain RANKIN 59 52.21 07 - CAPE BRETON EAST Total 113 100 Candidate Final Votes Points 08 - CHESTER - St. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 216, NO. 3 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 17, 2007 A certified copy of an Order in Council IN THE MATTER OF: The Companies Act, dated January 12, 2007 Chapter 81, R.S.N.S., 1989, as amended; - and - 2007-30 IN THE MATTER OF: An Application by 3077578 Nova Scotia Company for Leave to The Governor in Council is pleased to appoint, Surrender its Certificate of Amalgamation confirm and ratify the actions of the following Minister: To be Acting Minister of Service Nova Scotia and NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that 3077578 Nova Municipal Relations, Acting Minister responsible for Scotia Company intends to make an application to the the Residential Tenancies Act, and to be responsible for Registrar of Joint Stock Companies for leave to surrender any and all other duties assigned to that Minister from its Certificate of Amalgamation. 10:45 p.m., Friday, January 12, 2007 until 2:30 p.m., Sunday, January 21, 2007: the Honourable Angus DATED this January 17, 2007. MacIsaac. Charles S. Reagh / Stewart McKelvey Certified to be a true copy Solicitor for 3077578 Nova Scotia Company sgd: Paul LaFleche Paul LaFleche 114 January 17-2007 Clerk of the Executive Council IN THE MATTER OF: The Companies Act IN THE MATTER OF: The Companies Act, (Nova Scotia) Chapter 81, R.S.N.S., 1989, as amended; - and - - and - IN THE MATTER OF: An Application by IN THE MATTER OF: An Application by 3097430 Nova Scotia Limited for Leave to 3058351 Nova Scotia Corp. for Leave to Surrender its Certificate of Incorporation Surrender its Certificate of Incorporation NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that 3097430 Nova NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that 3058351 Nova Scotia Limited intends to make an application to the Scotia Corp. -

Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs ANNUAL REPORT

Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs ANNUAL REPORT 2018 © 2018 Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia Halifax ISSN: 1705-1541 This document is also available on the Internet at the following address: https://nslegislature.ca/legislative-business/committees/standing/veterans-affairs TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction i Membership i Membership Changes i Procedures and Operations i Notices, Transcripts and Reports ii Research Material iii Acknowledgements iii PUBLIC HEARINGS November 21, 2017 1 Organizational/Agenda-Setting Meeting December 12, 2017 3 Royal Canadian Legion Nova Scotia/Nunavut Command Re: Veterans Outreach Program January 23, 2018 6 Veterans’ Memorial Medical Centre Society Royal Canadian Legion Nova Scotia/Nunavut Command Re: Proposed Veterans’ Memorial Medical Centre February 20, 2018 9 Veterans Emergency Transition Services Canada Re: Boots on the Ground Campaign and Guitars for Vets May 15, 2018 12 The Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative Re: Veteran Trainers to Eradicate the Use of Child Soldiers (VTECS) June 19, 2018 14 Nova Scotia Health Authority Department of Health and Wellness Re: The Federal-Provincial Camp Hill Agreement Appendix A – Motions 17 Appendix B - Correspondance 20 Appendix C – Documentation 21 Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs 2018 Annual Report INTRODUCTION The Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs, an all-party committee of the House of Assembly, was struck at the beginning of the First Session of the Sixty-third General Assembly, pursuant to Rule 60(1) of the Province of Nova Scotia Rules and Forms of Procedure of the House of Assembly. Although there is no written mandate for the Standing Committee on Veterans Affairs, this report was written with the understanding that the committee is established for the purpose of considering matters pertaining to veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Legion. -

ATLANTIC OCEAN Gulf of Saint Lawrence 2012 PROVINCIAL

47.1° N 59.2° W Point Aconi Cape Dauphin Alder µ 50 10 Point 30 43 Middle Sackville Windsor Florence Junction Bras d'Or New Waterford 44 Sydney Mines Lingan Waverley Lower Sackville North Preston 18 38 50 Glace Bay Lake Echo North 29 Portobello 04 Sydney Gulf of Gardiner Mines Hammonds Plains Bedford 05 Preston South Bar 23 Saint Lawrence 17 16 Donkin Burnside Reserve Mines Mineville Marconi Towers Upper 49 Lawrencetown Whitney Pier 09 21 Grand Lake Road Dartmouth 13 Cole Harbour Leitches Creek 28 Westmount Timberlea Port Morien 19 Balls Creek 45 22 Birch Grove Sydney 26 Halifax Beechville 24 07 27 12 Cow Bay Sydney River Mira Road Eastern Passage 47 46 Homeville Fergusons See CBRM Inset 25 Cove µ Howie Centre Dutch Brook Hatchet Lake Hornes Road 32 1:150,000 1:140,000 49 HRM Inset CBRM Inset Northumberland Strait 46 14 06 39 15 11 41 02 40 48 20 Bay of Fundy 33 30 10 34 35 31 50 21 29 18 01 07 47 See HRM Inset 36 25 37 08 2012 Nova Scotia Electoral Districts 01 Annapolis 27 Halifax Citadel-Sable Island 02 Antigonish 28 Halifax Needham ATLANTIC OCEAN 03 Argyle-Barrington 29 Hammonds Plains-Lucasville 04 Bedford 30 Hants East 05 Cape Breton Centre 31 Hants West 06 Cape Breton-Richmond 32 Inverness 42 07 Chester-St. Margaret's 33 Kings North 08 Clare-Digby 34 Kings South 09 Clayton Park West 35 Kings West 51 10 Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley 36 Lunenburg 27 11 Colchester North 37 Lunenburg West Sable Island 12 Cole Harbour-Eastern Passage 38 Northside-Westmount 03 13 Cole Harbour-Portland Valley 39 Pictou Centre 14 Cumberland North 40 Pictou -

Personal Services Contracts, Based on Data Extracted from SAP on November 25, 2015

List of current Personal Services Contracts, based on data extracted from SAP on November 25, 2015 Approximate Employee Business Area Position Name Annualized Salary Ms Alyson Pierik Agriculture EA to Minister - Agriculture$ 69,573.92 Mr Stephen Moore Communications Nova Scotia Director, Communications$ 91,669.24 Ms Jalana Lewis Communities, Culture& Heritage Knowledge Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Nancy Radcliffe Communities, Culture& Heritage EA to Minister - CCH/African NS Affairs$ 69,573.92 Mr Terry Dixon Communities, Culture& Heritage Operations Lead $ 74,008.22 Ms Shalyn Jones Communities, Culture& Heritage Health Support Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Rhonda Atwell Communities, Culture& Heritage Facilitation Lead $ 74,849.32 Ms Lisa Bugden Communities, Culture& Heritage Director $ 135,644.08 Ms Nancy Baroni Community Services Project Director $ 79,999.92 Mr Aaron MacMullin Community Services EA to Minister - Community Services$ 69,573.66 Ms Joy Graham Educ & Early Childhood Develop EA to Minister-Educ. & Early Child.Dev$ 69,573.92 Ms Jessika-Jane Gilker Energy Legal Researcher $ 39,163.28 Mr Joshua Bragg Energy EA to Minister-Energy/Off of Acadian Aff$ 69,573.66 Mr Allan Billard Environment EA to Minister - Environment$ 69,573.92 Ms Courtney Bragg Executive Council Ex. Sect. to Chief of Staff$ 56,866.94 Ms Cleo Alexander Executive Council Administrative Assistant$ 45,768.32 Ms Lana M McGlinchey Executive Council Administrative Assistant$ 40,180.92 Mr Jason Kontak Executive Council Aboriginal Aff. & Comm Relations Officer$ 69,573.92 Ms Laurel Munroe -

Status of Electoral District Associations, June 24, 2021

Status of Electoral Districts Associations This webpage contains the registration status of electoral district associations (EDA) for all registered political parties, as of June 24, 2021. EDAs that have not registered The table below (based on the electoral districts as defined in the 2019 House of Assembly Act) lists, by electoral district and by party, the EDA registration status. Party: • Atlantica: Atlantica Party Association of Nova Scotia (No registered EDAs) • Green: Green Party of Nova Scotia • Liberal: Nova Scotia Liberal Party • NDP: Nova Scotia New Democratic Party • PC: The Progressive Conservative Association of Nova Scotia Status: • “Registered” indicates that the appropriate financial report and EDA registration form has been filed (Form 4 or Form 4-1) and accepted. • Grey (blank) indicates that the appropriate EDA registration form has not been filed and accepted. • “Suspended” indicates that an EDA has not filed their financial reports for the previous calendar year. Electoral District Green Liberal NDP PC 1 Annapolis Registered Registered Registered 2 Antigonish Registered Registered Registered 3 Argyle Registered Registered Registered 4 Bedford Basin Registered Registered Registered 5 Bedford South Registered Registered Registered 6 Cape Breton-Whitney Pier Registered Registered 7 Cape Breton East Registered Registered Registered 8 Chester-St. Margaret's Registered Registered Registered 9 Clare Registered Registered Registered 10 Clayton Park West Registered Registered Registered 11 Colchester-Musquodoboit Valley Registered -

Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Program Fiscal Year 2016-17: Proposed Renewal of Tax Relief and Additions to the Program

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.3.1 Halifax Regional Council January 24, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council Original Signed SUBMITTED BY: Ms. Sara Colburne, Vice Chair, Grants Committee DATE: November 8, 2016 SUBJECT: Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Program Fiscal Year 2016-17: Proposed Renewal of Tax Relief and Additions to the Program ORIGIN Motion passed at a meeting of the Grants Committee held on November 7, 2016. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Grants Committee Terms of Reference – “The HRM Grants Committee shall review, evaluate and make recommendations to Regional Council regarding annual cash grants, rent subsidies, property tax exemptions, less than market value property sales and leases to registered non-profit organizations and charities managed by a duly appointed Grants Committee.” RECOMMENDATION The Grants Committee recommend Regional Council adopt the amendments to Administrative Order 2014-001-ADM, the Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Administrative Order, as presented in the October 27, 2016 staff report, and as amended at the November 7, 2016 Grants Committee meeting. Tax Relief for Non-Profit Organizations Program Fiscal Year 2016-17: Proposed Renewal of Tax Relief and Additions to the Program Council Report - 2 - January 24, 2017 BACKGROUND At the Grants Committee meeting on November 7, 2016 staff presented the report on tax relief for non- profit organizations program fiscal year 2016-17: Proposed renewal of tax relief and additions to the program. The Committee considered the report. DISCUSSION In presenting the report, staff highlighted an error in the Background section of the report, page 2, paragraph 5 noting that the Dartmouth Lawn Bowls Club is effective April 1, 2017, and not recommended in fiscal year 2016-17 as stated. -

Relevant Resources for Socially and Environmentally Just Policies in Nova Scotia: a Bibliography (2Nd Edition)

Relevant Resources For Socially and Environmentally Just Policies in Nova Scotia: A Bibliography (2nd Edition) Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives January 2003 ISBN: 0-88627-301-3 Relevant Resources For Socially and Environmentally Just Policies in Nova Scotia: A Bibliography (2nd Edition) his second edition contains a list of research resources, sorted by topic, that are relatively Trecent (published in the last 12 years), are primari- ly focused upon Nova Scotia, and contribute to the production of socially and environmentally just policies in Nova Scotia. Melinda Krueger and Jim Sacouman of Acadia University compiled this second edition. All Research Associates of CCPA-NS were asked to offer amend- ments. This bibliography is an ongoing project. Please send any errors of inclusion and/or omission,or any other suggestions, to: “Bibliography” c/o CCPA-NS PO Box 8355 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3K 5M1 Phone:902-477-1252 Fax: 902-484-6344 e-mail: [email protected] 2 Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Contents Overview...................................................................... 4 Aboriginals................................................................. 5 Acadians..................................................................... 5 Anti-racism................................................................. 5 Black Nova Scotians................................................6 Community Development..................................... 6 Culture........................................................................