SC 67A CMP 05 Arabian Sea Humpback and Baleen Whale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section Iv District Profiles Awaran

SECTION IV DISTRICT PROFILES AWARAN Awaran district lies in the south of the Balochistan province. Awaran is known as oasis of AGRICULTURAL INFORMATION dates. The climate is that of a desert with hot summer and mild winter. Major crops include Total cultivated area (hectares) 23,600 wheat, barley, cotton, pulses, vegetable, fodder and fruit crops. There are three tehsils in the district: Awaran, Jhal Jhao and Mashkai. The district headquarter is located at Awaran. Total non-cultivated area (hectares) 187,700 Total area under irrigation (hectares) 22,725 Major rabi crop(s) Wheat, vegetable crops SOIL ATTRIBUTES Mostly barren rocks with shallow unstable soils Major kharif crop(s) Cotton, sorghum Soil type/parent material material followed by nearly level to sloppy, moderately deep, strongly calcareous, medium Total livestock population 612,006 textured soils overlying gravels Source: Crop Reporting Services, Balochistan; Agriculture Census 2010; Livestock Census 2006 Dominant soil series Gacheri, Khamara, Winder *pH Data not available *Electrical conductivity (dS m-1) Data not available Organic matter (%) Data not available Available phosphorus (ppm) Data not available Extractable potassium (ppm) Data not available Farmers availing soil testing facility (%) 2 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Farmers availing water testing facility (%) 0 (Based on crop production zone wise data) Source: District Soil Survey Reports, Soil Survey of Pakistan Farm Advisory Centers, Fauji Fertilizer Company Limited (FFC) Inputs Use Assessment, FAO (2018) Land Cover Atlas of Balochistan (FAO, SUPARCO and Government of Balochistan) Source: Information Management Unit, FAO Pakistan *Soil pH and electrical conductivity were measured in 1:2.5, soil:water extract. -

PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT

DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN: REGIONAL RIVALRIES, LOCAL IMPACTS Edited by Mona Kanwal Sheikh, Farzana Shaikh and Gareth Price DIIS REPORT 2012:12 DIIS REPORT This report is published in collaboration with DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 © Copenhagen 2012, the author and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: Protesting Hazara Killings, Press Club, Islamabad, Pakistan, April 2012 © Mahvish Ahmad Layout and maps: Allan Lind Jørgensen, ALJ Design Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-517-2 (pdf ) ISBN 978-87-7605-518-9 (print) Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk Mona Kanwal Sheikh, ph.d., postdoc [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Contents Abstract 4 Acknowledgements 5 Pakistan – a stage for regional rivalry 7 The Baloch insurgency and geopolitics 25 Militant groups in FATA and regional rivalries 31 Domestic politics and regional tensions in Pakistan-administered Kashmir 39 Gilgit–Baltistan: sovereignty and territory 47 Punjab and Sindh: expanding frontiers of Jihadism 53 Urban Sindh: region, state and locality 61 3 DIIS REPORT 2012:12 Abstract What connects China to the challenges of separatism in Balochistan? Why is India important when it comes to water shortages in Pakistan? How does jihadism in Punjab and Sindh differ from religious militancy in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)? Why do Iran and Saudi Arabia matter for the challenges faced by Pakistan in Gilgit–Baltistan? These are some of the questions that are raised and discussed in the analytical contributions of this report. -

Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons CMSI China Maritime Reports China Maritime Studies Institute 8-2020 China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon Conor M. Kennedy Peter A. Dutton Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports Recommended Citation Kardon, Isaac B.; Kennedy, Conor M.; and Dutton, Peter A., "China Maritime Report No. 7: Gwadar: China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan" (2020). CMSI China Maritime Reports. 7. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cmsi-maritime-reports/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the China Maritime Studies Institute at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in CMSI China Maritime Reports by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. August 2020 iftChina Maritime 00 Studies ffij$i)f Institute �ffl China Maritime Report No. 7 Gwadar China's Potential Strategic Strongpoint in Pakistan Isaac B. Kardon, Conor M. Kennedy, and Peter A. Dutton Series Overview This China Maritime Report on Gwadar is the second in a series of case studies on China’s Indian Ocean “strategic strongpoints” (战略支点). People’s Republic of China (PRC) officials, military officers, and civilian analysts use the strategic strongpoint concept to describe certain strategically valuable foreign ports with terminals and commercial zones owned and operated by Chinese firms.1 Each case study analyzes a different port on the Indian Ocean, selected to capture geographic, commercial, and strategic variation.2 Each employs the same analytic method, drawing on Chinese official sources, scholarship, and industry reporting to present a descriptive account of the port, its transport infrastructure, the markets and resources it accesses, and its naval and military utility. -

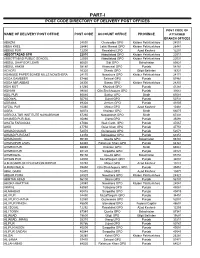

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

Tsunami Heights and Limits in 1945 Along the Makran Coast

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2021-53 Preprint. Discussion started: 5 March 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Tsunami heights and limits in 1945 along the 2 Makran coast estimated from testimony 3 gathered seven decades later in Gwadar, Pasni 4 and Ormara 5 Hira Ashfaq Lodhi1, Shoaib Ahmed2, Haider Hasan2 6 1Department of Physics, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 7 2 Department of Civil Engineering, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 8 Correspondence to: Hira Ashfaq Lodhi ([email protected]) 9 Abstract. 10 The towns of Pasni and Ormara were the most severely affected by the 1945 Makran tsuami. The water inundated almost a 11 kilometer at Pasni, engulfing 80% huts of the town while at Ormara tsunami inundated two and a half kilometers washing 12 away 60% of the huts. The plate boundary between Arabian plate and Eurasian plate is marked by Makran Subduction Zone 13 (MSZ). This Makran subduction zone in November 1945 was the source of a great earthquake (8.1 Mw) and of an associated 14 tsunami. Estimated death tolls, waves arrival times, extent of inundation and runup remained vague. We summarize 15 observations of tsunami through newspaper items, eye witness accounts and archival documents. The information gathered is 16 reviewed and quantized where possible to get the inundation parameters in specific and impact in general along the Makran 17 coast. The quantization of runup and inundation extents is based on a field survey or on old maps. 18 1 Introduction 19 The recent tsunami events of 2004 Indian Ocean (Sumatra) tsunami, 2010 (Chile) and 2011 (Tohoku) Pacific Ocean tsunami 20 have highlighted the vulnerability of coastal areas and coastal communities to such events. -

Balochistan Province Report on Mouza Census 2008

TABLE 1 NUMBER OF KANUNGO CIRCLES,PATWAR CIRCLES AND MOUZAS WITH STATUS NUMBER OF NUMBER OF MOUZAS KANUNGO CIRCLES/ PATWAR ADMINISTRATIVE UNIT PARTLY UN- SUPER- CIRCLES/ TOTAL RURAL URBAN FOREST URBAN POPULATED VISORY TAPAS TAPAS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 BALOCHISTAN 179 381 7480 6338 127 90 30 895 QUETTA DISTRICT 5 12 65 38 15 10 1 1 QUETTA CITY TEHSIL 2 6 23 7 9 7 - - QUETTA SADDAR TEHSIL 2 5 38 27 6 3 1 1 PANJPAI TEHSIL 1 1 4 4 - - - - PISHIN DISTRICT 6 17 392 340 10 3 8 31 PISHIN TEHSIL 3 6 47 39 2 1 - 5 KAREZAT TEHSIL 1 3 39 37 - 1 - 1 HURAM ZAI TEHSIL 1 4 16 15 - 1 - - BARSHORE TEHSIL 1 4 290 249 8 - 8 25 KILLA ABDULLAH DISTRICT 4 10 102 95 2 2 - 3 GULISTAN TEHSIL 1 2 10 8 - - - 2 KILLA ABDULLAH TEHSIL 1 3 13 12 1 - - - CHAMAN TEHSIL 1 2 31 28 1 2 - - DOBANDI SUB-TEHSIL 1 3 48 47 - - - 1 NUSHKI DISTRICT 2 3 45 31 1 5 - 8 NUSHKI TEHSIL 1 2 26 20 1 5 - - DAK SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 19 11 - - - 8 CHAGAI DISTRICT 4 6 48 41 1 4 - 2 DALBANDIN TEHSIL 1 3 30 25 1 3 - 1 NOKUNDI TEHSIL 1 1 6 5 - - - 1 TAFTAN TEHSIL 1 1 2 1 - 1 - - CHAGAI SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 10 10 - - - - SIBI DISTRICT 6 15 161 124 7 1 6 23 SIBI TEHSIL 2 5 35 31 1 - - 3 KUTMANDAI SUB-TEHSIL 1 2 8 8 - - - - SANGAN SUB-TEHSIL 1 2 3 3 - - - - LEHRI TEHSIL 2 6 115 82 6 1 6 20 HARNAI DISTRICT 3 5 95 81 3 3 - 8 HARNAI TEHSIL 1 3 64 55 1 1 - 7 SHARIGH TEHSIL 1 1 16 12 2 1 - 1 KHOAST SUB-TEHSIL 1 1 15 14 - 1 - - KOHLU DISTRICT 6 18 198 195 3 - - - KOHLU TEHSIL 1 2 37 35 2 - - - MEWAND TEHSIL 1 5 38 37 1 - - - KAHAN TEHSIL 4 11 123 123 - - - - DERA BUGTI DISTRICT 9 17 224 215 4 1 - 4 DERA BUGTI TEHSIL 1 -

Boundary Delineation and Renotification of Hingol National Park

Cover page design: GIS Laboratory, WWF – Pakistan Photo Credits: Irfan Ashraf and Hammad Gilani, WWF – Pakistan CONTENTS CONTENTS................................................................................................................................................................. I LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................................II LIST OF TABLES .....................................................................................................................................................II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................... III ACKNOWLEDGEMENT....................................................................................................................................... IV SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................................1 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................3 1.1 BACKGROUND.............................................................................................................................................3 1.2 STUDY AREA ..............................................................................................................................................4 -

Geographical Distribution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Sand Flies in Pakistan

Türkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi, 30 (1): 1 - 6, 2006 Acta Parasitologica Turcica © Türkiye Parazitoloji Derneği © Turkish Society for Parasitology Geographical Distribution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Sand Flies in Pakistan Ashraf SHAKİLA1, Fatima Mujib BİLQEES2, Azra SALİM3, Moinuddin4 1Institute of Hematology, Baqai Medical Karachi, Pakistan, 2Department of Zoology Jinnah University for Women Karachi; 3Jinnah University for Women Karachi, Pakistan, 4Institute of Haematology Baqai Medical University, Pakistan SUMMARY: Cutaneous leishmaniasis is found in all the four provinces of Pakistan; these are NWFP, Balochistan, Sindh and Punjab. In Balochistan the areas from where the patients came are Uthal, Quetta and Ormara. The highest number of patients came from Quetta and least from Ormara. The patients included in this study were from the Mangopir and Chakewara, areas of Karachi. The infection is endemic in this country and the recent epidemics in the Dadu District and Nawabshah indicate its importance in the locality. The sand fly vector is found in all four provinces of Pakistan that are listed here. It is quite obvious that presence of leishmaniasis indicates the presence of sand flies and cutaneous leishmaniasis is more common. Key Words: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, sand fly, geographical distribution, Pakistan Pakistan’da Kutanöz Leishmaniasis ve Kum Sineklerinin Coğrafik Dağılımı ÖZET: Kutanöz leishmaniasis, Pakistan’ın NWFP, Balochistan, Sindh ve Punjab bölgelerinde görülmektedir. Balochistan’da Uthal, Quetta ve Ormara bölgelerinden hastalar bulunmaktadır. En fazla hasta Quetta en az ise Ormara bölgesindendir. Bu çalışmaya alınan hastalar Karaçi’nin Mangopir ve Chakewara bölgelerindendir. Enfeksiyon bu ülkede endemiktir, Dadu Bölgesi ve Nawabshah’da mey- dana gelen son salgın enfeksiyonun bu lokalitelerde de önemli olduğunu göstermektedir. -

MARITIME TOURISM: GLOBAL SUCCESS STORIES and the CASE of PAKISTAN Naureen Fatima1 Muhammad Akhtar2

MARITIME TOURISM: GLOBAL SUCCESS STORIES AND THE CASE OF PAKISTAN Naureen Fatima1 Muhammad Akhtar2 Abstract The coastal / maritime tourism is an important segment in a multi-trillion dollars and multivariate global tourism industry. It offers one of the new avenues and fastest growing areas for significant role in global economies. Various countries such as Maldives, Indian State of Kerala, Singapore and Thailand etc. have focused on maritime tourism with good governance practices evolved over period of time to earn substantial revenues from it. Pakistan has also immense maritime tourism potential with diversified natural, religious, and cultural tourism resources. But Pakistan’s maritime tourism is considered very weak due to various issues. With qualitative research, this paper attempts to explore and suggest solutions for the development of maritime tourism sector of Pakistan by analysing the tourism governance of global success stories and evaluating the nationwide potential and challenges. Arguments are developed that the factors behind the success stories of Maldives & Kerala state in India can act as guidance for taking initiatives on the proposed potential sites in order to uplift the maritime tourism sector in Pakistan. It is anticipated that the effective implementation of this paper’s recommendations would be instrumental in gearing up Pakistan’s Maritime economy. Keywords: Coastal, Maritime, Maldives, Kerala, Tourism governance, Success stories, Potential sites Naureen Fatima is a Researcher- Maritime Tourism & Coastal Livelihoods at National Institute of Maritime Affairs (NIMA) reachable at [email protected] Muhammad Akhtar is Deputy Director at NCMPR Karachi reachable at [email protected] 2 Naureen Fatima, Muhammad Akhtar Introduction In this modern era, tourism has now grown to a multi-trillion dollars and multivariate trade activity across the globe. -

Hydel Power Potential of Pakistan 15

Foreword God has blessed Pakistan with a tremendous hydel potential of more than 40,000 MW. However, only 15% of the hydroelectric potential has been harnessed so far. The remaining untapped potential, if properly exploited, can effectively meet Pakistan’s ever-increasing demand for electricity in a cost-effective way. To exploit Pakistan’s hydel resource productively, huge investments are necessary, which our economy cannot afford except at the expense of social sector spending. Considering the limitations and financial constraints of the public sector, the Government of Pakistan announced its “Policy for Power Generation Projects 2002” package for attracting overseas investment, and to facilitate tapping the domestic capital market to raise local financing for power projects. The main characteristics of this package are internationally competitive terms, an attractive framework for domestic investors, simplification of procedures, and steps to create and encourage a domestic corporate debt securities market. In order to facilitate prospective investors, the Private Power & Infrastructure Board has prepared a report titled “Pakistan Hydel Power Potential”, which provides comprehensive information on hydel projects in Pakistan. The report covers projects merely identified, projects with feasibility studies completed or in progress, projects under implementation by the public sector or the private sector, and projects in operation. Today, Pakistan offers a secure, politically stable investment environment which is moving towards deregulation -

Enforced Disappearances by Pakistan Security Forces in Balochistan

Pakistan “We Can Torture, Kill, HUMAN RIGHTS or Keep You for Years” WATCH Enforced Disappearances by Pakistan Security Forces in Balochistan “We Can Torture, Kill, or Keep You for Years” Enforced Disappearances by Pakistan Security Forces in Balochistan Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 156432-786-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 51, Avenue Blanc 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2011 1-56432-786-8 “We Can Torture, Kill, or Keep You for Years” Enforced Disappearances by Pakistan Security Forces in Balochistan Map of Balochistan .......................................................................................................................... i Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology .................................................................................................................................. 9 I.