A Missionary Among the Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 179/Tuesday, September 15, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 15, 2020 / Notices 57231 of Federal Claims, the land from which Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Michigan State University is the Native American human remains Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Red responsible for notifying The Tribes, were removed is the aboriginal land of Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, The Consulted Tribes and Groups, and the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Minnesota; Saginaw Chippewa Indian The Invited Tribes that this notice has Tribe of Chippewa Indians of the Bad Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Marie been published. River Reservation, Wisconsin; Bay Mills Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan; Dated: August 14, 2020. Sokaogon Chippewa Community, Indian Community, Michigan; Melanie O’Brien, Chippewa Cree Indians of the Rocky Wisconsin; St. Croix Chippewa Indians Manager, National NAGPRA Program. Boy’s Reservation, Montana (previously of Wisconsin; and the Turtle Mountain listed as Chippewa-Cree Indians of the Band of Chippewa Indians of North [FR Doc. 2020–20295 Filed 9–14–20; 8:45 am] Rocky Boy’s Reservation, Montana); Dakota. BILLING CODE 4312–52–P Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and • Pursuant to 43 CFR 10.11(c)(1), the disposition of the human remains may Chippewa Indians, Michigan; DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, be to the Bad River Band of the Lake Michigan; Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians of National Park Service Lake Superior Chippewa Indians of the Bad River Reservation, Wisconsin; Wisconsin; Lac du -

Tribal Great Lakes Restoration Culturally Inspired Restoration Sabin Dam Removal - Grand Traverse Band

2019 Tribal Great Lakes Restoration Culturally Inspired Restoration Sabin Dam Removal - Grand Traverse Band Invasive Species Control - Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band Aerial Moose Survey - 1854 Treaty Authority Cover Photo: Wild Rice restored on Nottawa Creek near the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi Reservation Welcome Readers Dear Reader, The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) began in 2010 to accelerate efforts to protect and restore the Great Lakes. With the support of GLRI, tribes have substantially increased their capacity to participate in intergovernmental resource management activities for the Great Lakes alongside federal, state and other partners to address some of the most pressing challenges facing the Great Lakes. Indian country, comprised of reservation land bases and ceded territories where tribes retain rights, represents millions of acres within the Great Lakes Basin. Since 2010, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), with support from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, has provided GLRI funding to more than 30 tribes and tribal organizations in the Midwest and Eastern Regions for Great Lakes protection and restoration projects. The BIA GLRI program has gradually increased, growing from $3 million in 2010 to over $11 million in 2019. In total, BIA has provided approximately $60 million in GLRI funding to tribes as of fall 2019 to implement over 500 tribally led restoration projects. These projects protected and restored 190,000 acres of habitat and approximately 550 miles of Great Lakes tributaries, and include over 40 distinct projects to protect and restore native species. The majority of tribal GLRI projects work to assess, monitor, protect and restore local waterways, habitats, and species such as lake sturgeon, moose, and wild rice essential for tribal life-ways and cultural continuity. -

Restoring the Shiawassee Flats

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN SCHOOL OF NATURAL RESOURCES & ENVIRONMENT Restoring the Shiawassee Flats Estuarine Gateway to Saginaw Bay Prepared by: Janet Buchanan, Seta Chorbajian, Andrea Dominguez, Brandon Hartleben, Brianna Knoppow, Joshua Miller, Caitlin Schulze, Cecilia Seiter with historical land use analyses by Yohan Chang A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at the University of Michigan April 2013 Client: Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge Faculty advisors: Dr. Michael J. Wiley, Dr. Sara Adlerstein-Gonzalez, Dr. Kurt Kowalski (USGS-GLSC) Preface In 2011, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and Ducks Unlimited received a $1.5 million Sustain Our Great Lakes grant for the first phase of a wetland restoration project at the Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge, outside Saginaw, Michigan. The ambitious project seeks to hydrologically reconnect a 2,260-acre complex of bottomland farm fields and diked wetlands to the dynamic river systems surrounding the Refuge. The goals of this restoration are to provide fish, birds, and insects with access to a large, restored wetland complex both through hydrologic reconnection and wetland restoration; and to contribute to the delisting of at least three of the Beneficial Use Impairments in the Saginaw River/Bay Area of Concern, just downstream of the Refuge. Phase I of the restoration project involves the conversion of 940 acres of former farmland, now owned by the Refuge, to ecologically productive wetland, and its hydrologic reconnection to the Shiawassee and Flint Rivers. The grant for Phase I included enough funds to complete the design, engineering, and implementation of the project. -

2014 Southern Lake Huron Management Unit Newsletter

Southern Lake Fisheries D i v i s i o n Huron Management Michigan Department of natural Resources Unit Staff: I s s u e 2 FEBRUARY 2014 Todd Grischke , Lake Huron Basin Coordi- What is the SLHMU? nator The Southern Lake Huron Management Unit (SLHMU) encompasses the southern Michigan Jim Baker , Unit shores of Lake Huron including Saginaw Bay and all of the waters that make up the water- Manager sheds that drain into the southern portion of Lake Huron. Our work area includes all or por- Kathrin Schrouder , tions of the following counties: Arenac, Bay, Clare, Genesee, Gladwin, Gratiot, Huron, Iosco, Fisheries Manage- Isabella, Lapeer, Livingston, Midland, Mecosta, Montcalm, Oakland, Ogemaw, Roscommon, ment Biologist Saginaw, Sanilac, Shiawassee, St. Clair, and Tuscola. Fisheries staff working in this unit in- Joe Leonardi , Fisher- clude a Unit Manager and Management Biologist who work out of the Bay City Operations ies Management Biol- Service Center, a Management Biologist stationed at the Lapeer State Game Area, a technician ogist staff who work out of the Bay City Fisheries Warehouse, and 5 Fisheries Assistants (creel Chris Schelb , Fisher- clerks) who perform the Great Lakes creel census out of various ports. ies Technician Super- visor Who we are. Don Barnard , Fish- We are public trustees employed to fulfill the mission, vision, and values of the Michigan eries Technician DNR, Fisheries Division. Ryan Histed , Fisher- Fisheries Division Mission—to protect and enhance Michigan’s aquatic life and habitats for ies Technician the benefit of current and future generations. Vince Balcer , Fisher- Fisheries Division Vision –to provide world-class freshwater fishing opportunities, supported ies Technician by healthy aquatic environments, which enhance the quality of life in Michigan. -

2021 Sea Lamprey Control Program Treatment Schedule

2021 Lampricide Application Schedule (9/30/21) Treatment Window Station(s) Tributary County State/Province Lake Larvae Targeted Comments April 12-21 DFO Sterling Creek NY Ontario 39,828 Deferred April 12-21 DFO Ninemile Creek NY Ontario 56,167 Deferred April 26-30 DFO Snake Creek NY Ontario 7,766 Deferred April 26-30 DFO Catfish Creek NY Ontario 534 Deferred April 26-30 DFO Lindsey Creek NY Ontario 4,328 Deferred April 27 - May 6 MBS McKay Creek Mackinac MI Huron 7,296 April 27 - May 6 MBS Munuscong River (Taylor Creek) Chippewa MI Huron 23,240 April 27 - May 6 MBS Albany Creek Mackinac MI Huron 223 April 27 - May 6 MBS Whitefish River (Haymeadow Creek) Delta MI Michigan 2,624 April 27 - May 6 MBS Sugar Creek Menominee MI Michigan 641 April 27 - May 6 MBS Three Mile Creek Kewaunee WI Michigan 748 April 27 - May 6 LBS St. Joseph River (Pipestone Creek) Berrien MI Michigan 12,527 April 27 - May 6 LBS St. Joseph River (Farmer's Creek) Berrien MI Michigan 1,360 April 27 - May 6 LBS St. Joseph River (Hickory Creek) Berrien MI Michigan 2,368 May 10 - May 30 DFO South Sandy Creek NY Ontario 237,438 Deferred May 11- May 20 MBS Cedar River Menominee MI Michigan 139,165 May 11- May 20 MBS Valentine Creek Delta MI Michigan 6,191 May 11- May 20 MBS Arthur Bay Creek Menominee MI Michigan 1,280 May 11- May 20 LBS Hog Island Creek Mackinac MI Michigan 4,652 May 11- May 20 LBS Black River Mackinac MI Michigan 1,121 May 17-May 21 DFO Root River (Crystal Creek only) Ont Huron - May 25- May 28 DFO Watsons Creek Ont Huron 333 May 25 - June 3 MBS Traverse -

Saginaw River/Bay Fish Tainting BUI Removal Documentation (PDF)

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY GREAT LAKES NATIONAL PROGRAM OFFICE 77 WEST JACKSON BOULEVARD CHICAGO, IL 60604-3590 SEP 2 4 2008 Mail Code: R-19J James K. Cleland, Acting Chief Water Division Michigan Department of Environmental Quality P.O. Box 30273 Lansing, Michigan 48909 Dear Mr. Cleland: This letter is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) official response to your letter of July 21, 2008, requesting the delisting of the Tainting of Fish and Wildlife Flavor Beneficial Use Impairment (BUI) in the Saginaw River and Bay Area of Concern (AOC). As your request points out and the supplied data supports, the following restoration criteria for Tainting of Fish and Wildlife Flavor BUI in the Saginaw River and Bay AOC have been met: The Tainting of Fish and Wildlife Flavor BUI will be considered restored when: • No more than three reports offish tainting have been made to the MDNR or MDEQfor a period of three years; Or, if there have been reports oftaillfing: • A one-time analysis of representative fish species in an AOC in accordance with MDEQ's Great Lakes and Environmental Assessmellf Section (GLEAS) Procedure #55 for conducting taste and odor studies indicate that there is no tainting offish flavor. Based upon EPA's review of your request and the supporting data, and upon our shared desire to show progress as we move all of the Great Lakes AOCs toward restoration of all BUis and formal delisting, EPA approves your request for the delisting of the Tainting of Fish and Wildlife Flavor BUI in the Saginaw River and Bay AOC. -

Greatlakesbay Great Lakes Bay Regional Alliance Invites You to Participate Baldwin ��Esaning �Lio in Their Regional Trail Events and Get Involved in Their Mission

East Michigan Trails Elm 127 13 Guernsey 18 Clare 10 Washington Eddy Main St Tobacco Lewis Clarabella Rodgers Clarabella Brand S Curtis agi Curtis Herrick Herrick naw Herrick Rd 11 Mile 11 Isabella 10 Shearer Shearer Grass Lake Shearer County Line Rd Line County 30 127 Coleman Baker Shepherd Magrudder Hull Crawford Loomis Shaffer Water E Coleman Wise Coleman Saginaw Rd Killarney Beach Rd Doherty S Battle Fike Meridian Hope A S a Burns W Burns n Coleman G f 13 o N Lewis N 10 r Parish d Chippewa Dublin 75 I Geneva Mier Castor P Denver L er Maynard N a Tobico Barden e Eastman Ma k 23 Marsh r e A Rosebush qu Mackinaw Ruhle et W Rosebush te River Bay City Hope R Stark Meridian ail State Recreation B A Y T Seidlers Network Trail Regional Bay Lakes Great r Mile 5 ai Jefferson Area McNally l Bay County Riverwalk Castor Sanford Beaver 11 Mile 11 Wakerly Trail System Waldo Sturgeon Magrudder Stark 247 9 Mile 9 Townline 14 Kawkawlin SaginawWackerly Rd 10 Mile 10 7 Mile 7 10 Wheeler Wheeler Wheeler Isabella State 4 Mile 30 assee Swede w r a Wilder e Olson Northwood Eastman Midland i v University na w R agi Essexville Tittab S Mt Isabella 20 10 20 Nebobish Pleasant 20 Auburn Midland 10 75B 25 Pine River 2 Mile Mackinaw 4 Mile Ridge Chippewa River Chippewa Bay CCityity 22nd 127 Trail 75 Euclid Chippewa River Tuscola Hotchkiss Cass Gordonville Delta 47 Bullock College 2 Mile Patterson Poseyville East River Rd Delta River Rd German RailBayZil Trail Russell Green 23 Pine 15 Trails Legend Freeland Mackinaw 138 Freeland Rd Freeland Munger Saginaw Valley -

Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe Letter Re: Tribal Concerns

lD70 EAST BROl\DVVI:lY IV17~ PLEASAI\IT, P/fJCJ-!lGAN 48868 (989) 77 5--40 ! 4 F/tX (989) ?72.,4,151 November 20, 2012 Mary P. Logan Remedial Project Manager U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 77 W. Jackson Boulevard Chicago, Illinois 60604-3590 Re: Tribal concerns for culturally significant sites within the Tittabawassee River, Saginaw River & Bay Site, Michigan (Site) Dear Ms. Logan: The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan (Tribe) appreciates the efforts of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as you work towards a comprehensive evaluation of contamination in the Tittabawassee River and Saginaw River and Bay and associated floodplains. This letter focuses on Tribal historic preservation concerns and culturally significant sites relevant to the Tittabawassee River and Saginaw River and Bay area and provides a brief introduction to sites of tribal interest for EPA's consideration. The Tribe is concerned about the potential unearthing of culturally significant artifacts and/or remains. An accidental discovery plan and proper protocol needs to be in place prior to any earth moving. Consultation with appropriate Tribal contacts and the State Historical Preservation Office will identify key personnel to establish a chain of command. Also, appropriate agencies need to be identified and contact information provided in this plan. The Ziibiwing Cultural Center, although not an official Tribal Historic Preservation Office has, in the past acted in this capacity. As such, they have provided some historic maps and an inventory of culturally significant sites relevant to the Tittabawassee River and Saginaw River and Bay area. -

TARGETING ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION in the SAGINAW RIVER/BAY AREA of CONCERN (AOC) 2001 Remedial Action Plan Update July 2002

TARGETING ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION IN THE SAGINAW RIVER/BAY AREA OF CONCERN (AOC) 2001 Remedial Action Plan Update July 2002 Prepared for The Great Lakes Commission On behalf of The Partnership for the Saginaw Bay Watershed Prepared by Public Sector Consultants, Inc. Lansing, Michigan www.pscinc.com TARGETING ENVIRONMENTAL RESTORATION IN THE SAGINAW RIVER/BAY AREA OF CONCERN (AOC) 2001 Remedial Action Plan Update July 2002 Prepared for The Great Lakes Commission On behalf of The Partnership for the Saginaw Bay Watershed Prepared by Public Sector Consultants, Inc. Lansing, Michigan www.pscinc.com Project Director Mark Coscarelli Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................................... 1 The Saginaw Bay Watershed .......................................................................................... 3 Overview of Existing Conditions .................................................................................... 5 Measures of Success........................................................................................................ 6 Bay Ecosystem................................................................................................................. 15 Impairments................................................................................................................... 15 Evidence of Recovery................................................................................................... 17 Current Status ............................................................................................................... -

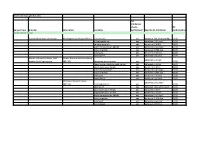

Internally Managed Datasets Service Type Provider Description Variables

Internally Managed Datasets QC Validation checks QC Service Type provider description variables performed? Specific QC Validation performed by GLOS Partner Buoys Grand Valley State University Muskegon Lake Buoy (GVSU1) air pressure yes between 700-1200 mmHg GLOS air temperature yes between 0-50 deg C GLOS relative humidity yes between 0-100% GLOS water temperature (@0ft) yes between 0-40 deg C GLOS wind direction yes between 0-360 deg GLOS wind gust yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS wind speed yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and Illinios-Indiana Sea Grant Buoy between 0-15 sec Purdue Civil Engineering (45170) dominant wave period yes GLOS mean wave direction peak period yes between 0-15 sec GLOS significant wave height yes between 0-10 m GLOS water temperature yes between 0-40 deg C GLOS wind direction yes between 0-360 deg GLOS wind gust yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS wind speed yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS Wilmette Weather Buoy between 0-50 deg C (45174) air temperature yes GLOS dew point yes between -30 and 50 deg C GLOS significant wave height yes between 0-10 m GLOS significant wave period yes between 0-15 sec GLOS water temperature (@0ft) yes between 0-40 deg C GLOS wind direction yes between 0-360 deg GLOS wind gust yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS wind speed yes between 0-50 m/s GLOS Internally Managed Datasets QC Validation checks QC Service Type provider description variables performed? Specific QC Validation performed by Limno Tech Cook Plant Buoy (45026) air temperature yes between 0-50 deg C GLOS dew point yes between -30 and -

Saginaw River NOAA Chart 14867

BookletChart™ Saginaw River NOAA Chart 14867 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the MI, on the west side just below Saginaw. Channels.–A Federal project provides for a dredged entrance channel National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration leading southwest from the deep water in Saginaw Bay for about 13.5 National Ocean Service miles to the mouth of the Saginaw River and thence upstream for about Office of Coast Survey 20 miles to the ports of Bay City and Saginaw. The entrance and river channels are well marked by lighted and unlighted buoys. www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov A 211°20' lighted range marks the entrance channel, and a 160° lighted 888-990-NOAA range marks a reach in the lower part of the river. The Federal project depths are 27 feet in the entrance channel to the What are Nautical Charts? mouth of the river, thence 26 feet through the mouth, thence 25 feet to the Canadian National Railroad bridge at Bay City, thence 22 feet to the Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show CSX railroad bridge in Saginaw. Four turning basins in the river have water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much project depths as follows: 25 feet at Essexville, 22 feet in Bay City more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and opposite the airport, 20 feet at Carrollton, and 20 feet just below the efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial CSX railroad bridge at Sixth Street in Saginaw. -

Eat Safe Fish in the Saginaw Bay Area

FREE LOCAL FISHING MAP Using the Eat Safe Fish Guidelines What are ‘safe’ fish? & Eat Safe Fish Guidelines MDHHS tests only the filets of the fish for Safe fishare fish that are low in chemicals to set these guidelines. MI Servings chemicals. If you use the Eat Safe are set to be safe for everyone. This includes children, pregnant or breastfeeding women, Fish Guide when you choose fish and people who have health problems like to catch and eat, you will protect cancer or diabetes. yourself and your family from chemicals that could someday How much is MI Serving? make you sick. eat Weight of Person MI Serving Size 45 pounds 2 ounces If there are chemicals in the fish, 90 pounds 4 ounces why should I still eat it? 180 pounds 8 ounces Fish have a lot of great health benefits. For every 20 pounds less than the weight listed in ; Fish can be a great low-fat the table, subtract 1 ounce of fish. safe For example, a 70-pound child’s MI Serving size is 3 ounces of fish. source of protein. 90 pounds - 20 pounds = 70 pounds & 4 ounces - 1 ounce = Weigh Less? Weigh a MI Serving size of 3 ounces ; Fish are brain food. For every 20 pounds more than the weight listed in ; Some fish have heart- the table, add 1 ounce of fish. For example, a 110-pound person’s MI Serving size is 5 ounces of fish. healthy omega-3s. 90 pounds + 20 pounds = 110 pounds / 4 ounces plus 1 ounce = a MI Serving size of 5 ounces fish More? Weigh Plus, fishing is a fun way to get outside and You might eat more than one MI Serving in a meal.