Criminal Prosecution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of the Office of District Attorney

AN OVERVIEW OF THE OFFICE OF DISTRICT ATTORNEY I. GENERAL INFORMATION FOR DISTRICT ATTORNEYS A. Authority 1. Louisiana Constitution Art. 5 Section 26 (B) Powers. Except as otherwise provided by this constitution, a district attor- ney, or his designated assistant, shall have charge of every criminal prosecu- tion by the state in his district, be the representation of the state before the grand jury in his district, and be the legal advisor of the grand jury. He shall perform other duties provided by law. 2. See also Code of Criminal Procedure Articles 61-66. The district attorney determines whom, when, and how to charge a State criminal law violation. Law enforcement agencies report to the district attor- ney on arrests made. He then evaluates (screening) each case based on the weight and admissibility of evidence in consideration of his greater burden of proof of guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.” His obligation is to seek justice rather than merely to convict. 3. Other statutory authority. There are numerous statutes authorizing the district attorney to enforce certain laws. Examples are enforcement of election code matters and open meeting requirements. B. DUTIES AND FUNCTIONS 1. Criminal Duties a. Receive, data entry (case management system) and review(screen) all post arrest criminal files submitted for prosecution by local, parish, state and federal law enforcement agencies to determine the nature of the charges(probable cause for arrest) and weight of evidence for prosecution and to take one or more of the following actions: (1) If accepting or amending submitted charges, prepare bills of information. (2) If accepting charges but defendant qualifies for diversion, refer to diversion program (PTI). -

Jeffrey Brown

Jeffrey A. Brown Partner New York | Three Bryant Park, 1095 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY, United States of America 10036-6797 T +1 212 698 3511 | F +1 212 698 3599 [email protected] Services Litigation > White Collar, Compliance and Investigations > Anti-Corruption Compliance and Investigations > Asset Management Litigation/Enforcement > Automotive and Transportation > Banking and Financial Institutions > Jeffrey A. Brown focuses his practice on white collar defense, securities litigation, SEC and CFTC enforcement actions, and related commercial litigation. His experience includes conducting internal investigations across multiple industries and across international boundaries, representing companies and individuals in connection with investigations by the Department of Justice, the Securities Exchange Commission, and state and local prosecutors. Mr. Brown’s practice includes a number of matters representing individuals investigated for “spoofing” and other market manipulation in markets for various commodities. Mr. Brown previously worked for approximately 9 years at the United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York, where he served as Co-Chief of the General Crimes Unit and before that as Acting Deputy Chief of the Narcotics Unit. As an Assistant U.S. Attorney, Mr. Brown investigated and prosecuted crimes in the Terrorism, International Narcotics Trafficking, Narcotics, Violent Crimes and General Crimes Units. Many of Mr. Brown’s representations at Dechert involve investigations brought by his former Office. The recipient of the 2011 Attorney General’s Distinguished Service Award, during his time at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, he prosecuted several high-profile cases, including United States v. Faisal Shahzad, the Times Square bomber, and United States v. -

Hiring Practices of California District

HIRING PRACTICES OF CALIFORNIA DISTRICT ATTORNEY OFFICES 2017-2018 County Map of California 2 3 California District Attorney Office Hiring Practices INTRODUCTION This directory was compiled by the UC Davis School of Law in the Spring of 2017. It contains information about student and attorney positions at district attorney offices throughout California. This information is based on entries in an earlier directory, previous job listings, web site information, and follow-up telephone calls. Some counties conduct on campus interviews for third year students or both second and third year students at several law schools in the fall. The UC Davis School of Law will advertise these opportunities. Please note that you should always verify the names of any hiring attorney or District Attorney, and the office address, before corresponding with these offices. Before any interview, you should research each particular office and the background of the District Attorney. Also, hiring practices can change at any time due to changes in budgets and turnover. If you are particularly interested in a county, it is recommended that you contact the representative listed, the district attorney office, or the county’s personnel office directly to determine hiring needs. The vast majority of the offices are very helpful and willing to provide necessary information to those who are interested. Another great resource for finding employment opportunities in prosecution is the California District Attorneys’ Association website. The association’s web address is www.cdaa.org. Good luck! 4 Table of Contents Alameda ................................................. 4 Placer ..................................................... 25 Alpine ..................................................... 5 Plumas .................................................... 25 Amador .................................................. 5 Riverside ...................................................26 Butte ....................................................... 5 Sacramento ............................................ -

Traffic Tickets-**ITHACA CITY COURT ONLY

The Ithaca City Prosecutor’s Office prosecutes traffic tickets within the City of Ithaca and as part of that responsibility also makes offers to resolve tickets in writing. Please note that written dispositions can only be accommodated in cases in which the charges do not involve misdemeanors. If you are charged with any misdemeanor, including Driving While Intoxicated or Aggravated Unlicensed Operation you must appear in person in Court. The following applies to traffic tickets in the City of Ithaca that are not misdemeanors. All questions about fines, penalties and rescheduling of court dates/appearances must be addressed to the Court. If you have an upcoming Court date on a traffic ticket, only the Court can excuse your appearance. If you fail to appear in Court, the Court can suspend your driver license. If you wish to request that an upcoming appearance be rescheduled to allow time to correspond with our office, you must contact the Court directly. Contact information for the Ithaca City Court can be found here How to Request an Offer to Resolve Your Traffic Ticket Pending in Ithaca City Court Due to the large volume of the traffic caseload we only respond to email requests. Please do not use mail, fax or phone calls to solicit an offer. Please do not contact the Tompkins County District Attorney, the Tompkins County Attorney, or the Ithaca City Attorney- only the Ithaca City prosecutor. To confirm that this is the correct court, check the bottom left of your ticket- it should state that the matter is scheduled for Ithaca City Court, 118 East Clinton Street. -

District Attorney

GENERAL FUND DEPARTMENTS: Administration of Justice DISTRICT ATTORNEY MISSION The Fort Bend County District Attorney’s office represents the people of the State of Texas in all felony and misdemeanor criminal cases in the District Courts, County Courts at-Law, and Justice Courts. It is the primary duty of the District Attorney and his assistants, not to convict, but to see that justice is done. Additionally, the District Attorney represents the State in asset forfeiture cases, bond forfeiture cases, juvenile matters, and protective orders as well as aiding crime victims through its victim assistance coordinator. GOALS GOAL 1 Provide effective prosecution in all courts in order to effectively move the dockets while ensuring justice. Objective 1 Recruitment of prosecutors requires that we continue our dynamic internship program, whereby students are allowed to work and learn in a courtroom environment. Objective 2 Become more competitive with Harris County for prosecutors, and pay them at least 90 percent of what Harris County does. Objective 3 Upgrade positions to keep the best prosecutors. Currently, the office trains prosecutors to become excellent lawyers, only to have them leave (and take the County’s investment with them). A salary, which is more competitive with Harris County, should be achieved. GOAL 2 To improve prosecution in services, in order to ensure justice. Objective 1 Add assistants commensurate with the creation of new courts and increased caseload. Objective 2 As soon as practical, create an additional position for another full-time Assistant District Attorney to concentrate on filing of cases in the intake division. GOAL 3 Increase services to victims of family violence, in order to enhance education and protection of the public. -

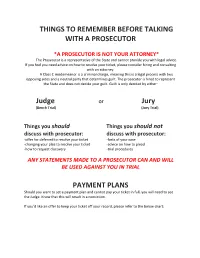

Things to Remember Before Talking with a Prosecutor

THINGS TO REMEMBER BEFORE TALKING WITH A PROSECUTOR *A PROSECUTOR IS NOT YOUR ATTORNEY* The Prosecutor is a representative of the State and cannot provide you with legal advice. If you feel you need advice on how to resolve your ticket, please consider hiring and consulting with an attorney. A Class C misdemeanor is a criminal charge, meaning this is a legal process with two opposing sides and a neutral party that determines guilt. The prosecutor is hired to represent the State and does not decide your guilt. Guilt is only decided by either: Judge or Jury (Bench Trial) (Jury Trial) Things you should Things you should not discuss with prosecutor: discuss with prosecutor: -offer for deferred to resolve your ticket -facts of your case -changing your plea to resolve your ticket -advice on how to plead -how to request discovery -trial procedures ANY STATEMENTS MADE TO A PROSECUTOR CAN AND WILL BE USED AGAINST YOU IN TRIAL PAYMENT PLANS Should you want to set a payment plan and cannot pay your ticket in full, you will need to see the Judge. Know that this will result in a conviction. If you’d like an offer to keep your ticket off your record, please refer to the below chart: How To Resolve Your Case With The Prosecutor Do you want an offer to pay for your ticket? YES NO Do you want to accept the offer No Set for trial that has been made? YES Do you need more time to save for the offer? YES NO Ask Judge for a Complete deferred continuance if you agreement and haven't had one. -

Julie Garcia District Attorney (Fmr.) Essex County, NY

Julie Garcia District Attorney (Fmr.) Essex County, NY Julie Garcia began her legal career in 1999 as an assistant district attorney within the Domestic Violence Unit of the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office in New York, where she successfully prosecuted hundreds of domestic violence cases. In 2000, she moved to upstate New York to work in the Rensselaer County District Attorney’s Office and to be closer to family. After the death of her sister, she raised her two nieces and ran her own law firm, handling cases in Federal Court, Supreme Court, Family Court, County Court, and local courts for close to 20 years. In 2005, she made history by becoming the first woman elected District Attorney of Essex County. Her tenure as DA was focused on working to proactively reduce crime by collaborating with treatment agencies, law enforcement, probation, and other organizations to decrease underage drinking, driving while intoxicated, drug abuse, and domestic violence. Garcia left the District Attorney’s Office in 2009 and has since worked in private practice. She is a commissioner on the New York State Joint Commission on Public Ethics and is a sitting board member of the Legal Aid Society of Northeastern New York. She is a member of the Warren County Bar Association, Essex County Bar Association, Adirondack Women’s Bar Association, and New York State Defenders Association. She holds a BA in social work from Siena College and a JD from Albany Law School. The Law Enforcement Action Partnership is a nonprofit organization composed of police, prosecutors, judges, and other criminal justice professionals who use their expertise to advance drug policy and criminal justice solutions that improve public safety. -

The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2001 The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal Profession Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Angela J., "The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny" (2001). Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals. 1397. https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev/1397 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American Prosecutor: Independence, Power, and the Threat of Tyranny AngelaJ. Davis' INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 395 I. DISCRETION, POWER, AND ABUSE ......................................................... 400 A. T-E INDF-ENDENT G E z I ETu aAD RESPO,\SE.................... -

DADISPATCH FANI T. WILLIS, District Attorney

June 2021 | Issue II DADISPATCH FANI T. WILLIS, District Attorney The Fulton County District Attorney’s Office Introducing Robin’s Left-Hand Man Hi there! My name is Jeremy and I am so excited to help launch our latest project the DA Dispatch as the Managing Editor for this exciting project. For those of you who may not know me - I am one of Madam DA’s Executive Assistants. A little bit about me: I am originally from Tennessee and moved to Atlanta in 2016 to pursue a career in politics. Little did I know my journey would go from interning to managing local, statewide, as well as out of state campaigns. In addition to working on some coordinated campaigns for President. My life went from spending time in the mountains of TN and NC and paddle boarding at the lake to spending most of my days chatting it up with the late Congressman John Lewis, Hillary Clinton, President Biden, Congresswoman Jahana Hayes, Senator Jon Ossoff, various Governors and celebrity donors, getting flown around in helicopters, riding in armored vehicles, and more. Campaign work also gave me the flexibility to travel – something that I had always aspired to do. During my time off from the hectic campaign trail, you could find me “on tour” visiting places like Colombia, Cuba, or sailing the Narragansett. I am honored to be a part of Madam DA’s administration – one that is historic for numerous reasons. Like VP Kamala Harris famously has said, “You may be the first to do many things, but make sure you’re not the last.” I have spent FULTONCOUNTYDA the past 5 years fighting to get people like Madam DA elected because we need more women and women of color in elected leadership positions. -

Criminal Prosecution Guide

CAREER DEVELOPMENT OFFICE JOB GUIDE CRIMINAL PROSECUTION Description Types of Employers Prosecutors work in all levels of government–local, state, Federal—U.S. Department of Justice: and federal. Prosecutors are responsible for representing the government in criminal cases, including Post-Graduate Jobs. The DOJ hires entry-level attorneys felonies and misdemeanors. At the state and local level, only through the Attorney General’s Honors Program. this work is typically done by District Attorneys’ Offices The application period is very short, typically the month or Solicitors’ Offices. Offices of State Attorneys General of August in the year prior to your graduation year. The may also have some responsibility for criminal matters of number of attorneys hired varies from year to year, and statewide significance or for criminal appellate or post- the positions are highly competitive. conviction matters. Federal criminal matters (e.g., financial crimes, drug enforcement, and organized Paid Summer Internships. The DOJ hires a number of crime) are typically handled by a U.S. Attorney’s Office students for paid summer positions through its Summer (USAO) either exclusively or in cooperation with the Law Intern Program. These positions are open to 1Ls Criminal Division of the Office of the U.S. Attorney and 2Ls, although most successful applicants intern General. during their 2L summer. Graduating law students who will enter a judicial clerkship or a full-time graduate program may intern following graduation. The application Qualifications period is very short, typically the month of August in the year prior to the summer you would be working. Many prosecutors’ offices prefer that entry-level attorneys have coursework, summer experience and/or Unpaid Internships. -

Scanned Document

Martin Placke Lee County Attorney Pamela Giese Assistant Lee County Casandra Collins Attorney ------------- OFFICE OF THE Secretary ------------- Hot Check Division LEE COUNTY ATTORNEY ~dolph E. Voigt LEE COUNTY COURTHOUSE Assistant Lee Coun!J:. Christina Navarro Attorney KECEIVED 200 South Main, Room 305 Secretary Giddings, Texas 78942 Misdemeanor Division OCT O4 2016 979-542-3233 Fax:979-542-1226 OPINION COMMITTEE Offic of the Attorney General Atte tion Opinion Committee R~-013i.-KP P.O. Box 12548 Austl ,~ 7871 - Dear Attorney"'" General Paxton and Opinion Committee: The Lee County Attorney requests the opinion of the Texas Attorney General regarding which type of bond (or bonds) is required for a county attorney who has both felony and misdemeanor jurisdiction. Background: Article V, Section 21 of the Texas Constitution provides: Sec. 21. COUNTY ATTORNEYS; DISTRICT ATTORNEYS. A County Attorney, for counties in whiqh there is not a resident Criminal District Attorney, shall be elected by the qualified voters of each county, who shall be commissioned by the Governor, and hold his office for the term of four years. In case of vacancy the Commissioners Court of the county ·shall have the power to appoint a County Attorney until the next general election. The County Attorneys shall represent the State in all cases in the District and inferior courts in their respective counties; but if any county shall be included in a district in which there shall be a District Attorney, the respective duties of District Attorneys and County Attorneys shall in such counties be regulated by the Legislature. The Legislature may provide for the election of District Attorneys in such districts, as may be deemed necessary, and make provision for the compensation of District Attorneys and County Attorneys. -

Judge Alphabetical Name Index

ALPHABETICAL NAME INDEX Agati, Salvatore C. Judge, Connecticut Superior Albers, Ronald E. Judge, Superior Court of Cali- Alfeld, Philip B. Associate Judge, Illinois Circuit Court, CT fornia City and County of San Francisco Mental Courts - Third Judicial Circuit Madison, IL Agbayani, Antonino J. Judge, Superior Court of Health, CA Alfieri, Victor J., Jr. Justice, New York Supreme California County of San Joaquin Family, CA Albert, Janet E. Magistrate Judge, Superior Court - Ninth Judicial District, NY; Judge, New Agee, G. Steven Judge, United States Court of Court of the District of Columbia Family, Neglect York County Court Rockland, NY Appeals for the Fourth Circuit & Abuse, DC Alfonso, Margaret Judge, Mississippi County Agerton, Doug Judge, Alabama Probate Courts Albert, Michael R. Associate Judge, Illinois Cir- Courts Harrison, MS Escambia, AL cuit Courts - Fourteenth Judicial Circuit White- Alford, Benjamin G. Senior Resident Judge, Agnes, Peter W., Jr. Associate Justice, Massa- side, IL North Carolina Superior Courts - District 3B, NC chusetts Appeals Court, MA Albert, Theodor C. Judge, United States Bank- Alford, Gary R. Judge, City Courts in New York Agostini, John A. Associate Justice, Massachu- ruptcy Court Central District of California Santa Ogdensburg, NY setts Superior Court Department, MA Ana, CA Alford, Lee S. Retired Judge, South Carolina Cir- Albertson, Bruce D. Judge, Virginia Circuit Agran, Martin S. Circuit Judge, Illinois Circuit cuit Court - Sixteenth Judicial Circuit, SC Courts - Twenty-Sixth Judicial Circuit, VA Courts - Circuit Court of Cook County Cook, IL Alford, Margaret L. District Magistrate Judge, Albin, Barry T. Associate Justice, Supreme Kansas District Court - Twenty-Sixth Judicial Dis- Agresti, Thomas P.