SUNY Albany Concept Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mohawk River Watershed – HUC-12

ID Number Name of Mohawk Watershed 1 Switz Kill 2 Flat Creek 3 Headwaters West Creek 4 Kayaderosseras Creek 5 Little Schoharie Creek 6 Headwaters Mohawk River 7 Headwaters Cayadutta Creek 8 Lansing Kill 9 North Creek 10 Little West Kill 11 Irish Creek 12 Auries Creek 13 Panther Creek 14 Hinckley Reservoir 15 Nowadaga Creek 16 Wheelers Creek 17 Middle Canajoharie Creek 18 Honnedaga 19 Roberts Creek 20 Headwaters Otsquago Creek 21 Mill Creek 22 Lewis Creek 23 Upper East Canada Creek 24 Shakers Creek 25 King Creek 26 Crane Creek 27 South Chuctanunda Creek 28 Middle Sprite Creek 29 Crum Creek 30 Upper Canajoharie Creek 31 Manor Kill 32 Vly Brook 33 West Kill 34 Headwaters Batavia Kill 35 Headwaters Flat Creek 36 Sterling Creek 37 Lower Ninemile Creek 38 Moyer Creek 39 Sixmile Creek 40 Cincinnati Creek 41 Reall Creek 42 Fourmile Brook 43 Poentic Kill 44 Wilsey Creek 45 Lower East Canada Creek 46 Middle Ninemile Creek 47 Gooseberry Creek 48 Mother Creek 49 Mud Creek 50 North Chuctanunda Creek 51 Wharton Hollow Creek 52 Wells Creek 53 Sandsea Kill 54 Middle East Canada Creek 55 Beaver Brook 56 Ferguson Creek 57 West Creek 58 Fort Plain 59 Ox Kill 60 Huntersfield Creek 61 Platter Kill 62 Headwaters Oriskany Creek 63 West Kill 64 Headwaters South Branch West Canada Creek 65 Fly Creek 66 Headwaters Alplaus Kill 67 Punch Kill 68 Schenevus Creek 69 Deans Creek 70 Evas Kill 71 Cripplebush Creek 72 Zimmerman Creek 73 Big Brook 74 North Creek 75 Upper Ninemile Creek 76 Yatesville Creek 77 Concklin Brook 78 Peck Lake-Caroga Creek 79 Metcalf Brook 80 Indian -

113 Hudson River Basin 01350101 Schoharie Creek At

HUDSON RIVER BASIN 113 01350101 SCHOHARIE CREEK AT GILBOA, NY LOCATION.--Lat 42°23'50", long 74°27'03", Schoharie County, Hydrologic Unit 02020005, on left bank 200 ft upstream from bridge on County Highway 322, 0.2 mi west of village of Gilboa, 0.4 mi downstream from dam on Schoharie Reservoir, and 0.8 mi upstream from the Platter Kill. DRAINAGE AREA.--316 mi2. PERIOD OF RECORD.--October 1975 to current year (since October 1983, discharges only for days of Schoharie Reservoir spill and since October 1989, discharges only for days of mean flow exceeding 10 ft3/s). REVISED RECORDS.--WDR NY-90-1: Drainage area. GAGE.--Water-stage recorder and crest-stage gage. Datum of gage is 939.56 ft above NGVD of 1929. REMARKS.--Records fair except those for estimated daily discharges, which are poor. Entire flow, runoff from 315 mi2, except for periods of spill, diverted from Schoharie Reservoir through Shandaken Tunnel into Esopus Creek upstream from Ashokan Reservoir for water supply of city of New York. Satellite gage-height telemeter at station. EXTREMES FOR PERIOD OF RECORD.--Maximum discharge, 70,800 ft3/s, Jan. 19, 1996, gage height, 30.60 ft, outside gage height, 32.2 ft, from floodmark, from rating curve extended above 14,000 ft3/s on basis of flow-over-dam measurement of peak flow; minimum daily discharge, 0.04 ft3/s on many days, June to October 1976, and Sept. 11-13, 1980, but may have been lower since October 1983 (see PERIOD OF RECORD); minimum instantaneous discharge not determined. -

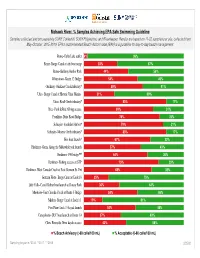

Explore Data from Each Sampling Site, Year-To-Year Patterns

Mohawk River: % Samples Achieving EPA Safe Swimming Guideline Samples collected and processed by SUNY Cobleskill, SUNY Polytechnic and Riverkeeper. Results are based on 11-32 samples per site, collected from May-October, 2015-2019. EPA's recommended Beach Action Value (BAV) is a guideline for day-to-day beach management. Rome- Delta Lake outlet 4% 96% Rome- Barge Canal at city boat ramp 33% 67% Rome- Bellamy Harbor Park 44% 56% Whitestown- Route 32 Bridge 54% 46% Oriskany- Oriskany Creek tributary* 59% 41% Utica- Barge Canal at Historic Utica Marina 31% 69% Utica- Reall Creek tributary* 83% 17% Utica- Park & Ride fishing access 69% 31% Frankfort- Dyke Road Bridge 76% 24% Schuyler- Frankfort Harbor* 79% 21% Schuyler- Moyers Creek tributary* 83% 17% Ilion boat launch* 67% 33% Herkimer- Gems Along the Mohawk kayak launch 57% 43% Herkimer- I-90 bridge*** 64% 36% Herkimer- Fishing access at STP 75% 25% Herkimer- West Canada Creek at East German St. Ext 68% 32% German Flatts- Barge Canal at Lock 18 25% 75% Little Falls- Canal Harbor boat launch at Rotary Park 36% 64% Manheim- East Canada Creek at Route 5 Bridge 54% 46% Minden- Barge Canal at Lock 16 19% 81% Fort Plain- Lock 15 kayak launch 52% 48% Canajoharie- DEC boat launch at Route 10 37% 63% Glen- Riverside Drive kayak access 42% 58% % Beach Advisory (>60 cells/100 mL) % Acceptable (0-60 cells/100 mL) Sampling began in *2016, **2017, ***2018 2/25/20 Mohawk River: % Samples Achieving EPA Safe Swimming Guideline Samples collected and processed by SUNY Cobleskill, SUNY Polytechnic and Riverkeeper. -

Ashokan Watershed Adventure Guide

ASHOKAN WATERSHED ADVENTURE GUIDE A Self-Guided Tour of the Ashokan Landscape for All Ages #AshokanWatershedAdventure AWSMP Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program The Ashokan Watershed Adventure is sponsored by: AWSMP Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program Cornell Cooperative Extension Ulster County AWSMP Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program About the Ashokan Watershed Adventure The Ashokan Watershed Adventure is a self-guided tour of the AshokanAshokan landscape Watershed for all ages. Adventurers explore the Ashokan Reservoir watershed at theirSt rowneam Managementpace and earn Program prizes based on the number of Adventure Stops visited. From the humble headwaters of the Stony Clove Creek to the shores of the mighty Ashokan Reservoir, Adventurers will experience the landscape like never before. Adventure Stops have been thoughtfully curated by Ashokan Watershed Stream Management Program (AWSMP) staff to highlight some of the most interesting and beautiful places in the watershed. Grab your friends and family or head out on your very own Ashokan Watershed Adventure! How it works Pre-adventure planning There are 11 Ashokan Watershed Adventure Stops. Visit as As with any adventure into the wild lands of the Catskill many as you can to earn a prize. Adventure stops can be Mountains, planning is a very important part of having a fun visited in any order. Each stop has a chapter in the Adventure and safe experience. Guide that includes the site name and location, geographic coordinates, directions and parking instructions, safety guide- 3Cell phone service is limited to non-existent. We lines, and an educational message to inform Adventurers recommend downloading a map of the area to your phone about the unique aspects of the site. -

Freshwater Fishing: a Driver for Ecotourism

New York FRESHWATER April 2019 FISHINGDigest Fishing: A Sport For Everyone NY Fishing 101 page 10 A Female's Guide to Fishing page 30 A summary of 2019–2020 regulations and useful information for New York anglers www.dec.ny.gov Message from the Governor Freshwater Fishing: A Driver for Ecotourism New York State is committed to increasing and supporting a wide array of ecotourism initiatives, including freshwater fishing. Our approach is simple—we are strengthening our commitment to protect New York State’s vast natural resources while seeking compelling ways for people to enjoy the great outdoors in a socially and environmentally responsible manner. The result is sustainable economic activity based on a sincere appreciation of our state’s natural resources and the values they provide. We invite New Yorkers and visitors alike to enjoy our high-quality water resources. New York is blessed with fisheries resources across the state. Every day, we manage and protect these fisheries with an eye to the future. To date, New York has made substantial investments in our fishing access sites to ensure that boaters and anglers have safe and well-maintained parking areas, access points, and boat launch sites. In addition, we are currently investing an additional $3.2 million in waterway access in 2019, including: • New or renovated boat launch sites on Cayuga, Oneida, and Otisco lakes • Upgrades to existing launch sites on Cranberry Lake, Delaware River, Lake Placid, Lake Champlain, Lake Ontario, Chautauqua Lake and Fourth Lake. New York continues to improve and modernize our fish hatcheries. As Governor, I have committed $17 million to hatchery improvements. -

Town of Lexington Draft Long Term Community Recovery Strategy

Town of Lexington Draft Long Term Community Recovery Strategy September 2014 i This page intentionally left blank ii Acknowledgements Town of Lexington Town Board Dixie Baldrey, Supervisor Jo Ellen Schermerhorn William Pushman Michael Barcone Bradley Jenkins Long Term Community Recovery Strategy Steering Committee Dixie Baldrey Mary Palazzolo Lynn Byrne Joe Cuesta Karen Deeter Bonnie Blader Beverly Dezan Adam Cross Alice M. Cross Rose Williams Andy Labruzzo, NYS Department of State Consultants Nan Stolzenburg, AICP CEP, Community Planning & Environmental Associates Don Meltz, AICP, Don Meltz Planning & GIS Ellen Pemrick, E.M. Pemrick & Company Ben Syden, Laberge Group Adam Yagelski, Community Planning & Environmental Associates This Plan was prepared for the New York State Department of State with funds provided under Title 3 of the Environmental Protection Fund Act. iii Table of Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................................. v Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction and Flood Event Background ..................................................................... 7 Flooding From Hurricane Irene .................................................................................................... 8 The Planning Process .......................................................................................................... -

Distribution of Ddt, Chlordane, and Total Pcb's in Bed Sediments in the Hudson River Basin

NYES&E, Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring 1997 DISTRIBUTION OF DDT, CHLORDANE, AND TOTAL PCB'S IN BED SEDIMENTS IN THE HUDSON RIVER BASIN Patrick J. Phillips1, Karen Riva-Murray1, Hannah M. Hollister2, and Elizabeth A. Flanary1. 1U.S. Geological Survey, 425 Jordan Road, Troy NY 12180. 2Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Troy NY 12180. Abstract Data from streambed-sediment samples collected from 45 sites in the Hudson River Basin and analyzed for organochlorine compounds indicate that residues of DDT, chlordane, and PCB's can be detected even though use of these compounds has been banned for 10 or more years. Previous studies indicate that DDT and chlordane were widely used in a variety of land use settings in the basin, whereas PCB's were introduced into Hudson and Mohawk Rivers mostly as point discharges at a few locations. Detection limits for DDT and chlordane residues in this study were generally 1 µg/kg, and that for total PCB's was 50 µg/kg. Some form of DDT was detected in more than 60 percent of the samples, and some form of chlordane was found in about 30 percent; PCB's were found in about 33 percent of the samples. Median concentrations for p,p’- DDE (the DDT residue with the highest concentration) were highest in samples from sites representing urban areas (median concentration 5.3 µg/kg) and lower in samples from sites in large watersheds (1.25 µg/kg) and at sites in nonurban watersheds. (Urban watershed were defined as those with a population density of more than 60/km2; nonurban watersheds as those with a population density of less than 60/km2, and large watersheds as those encompassing more than 1,300 km2. -

The New York State Flood of July 1935

Please do not destroy or throw away this publication. If you have no further use for it write to the Geological Survey at Washington and ask for a frank to return it UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 773 E THE NEW YORK STATE FLOOD OF JULY 1935 BY HOLLISTER JOHNSON Prepared in cooperation with the Water Power and Control Commission of the Conservation Department and the Department of Public Works, State of New York Contributions to the hydrology of the United States, 1936 (Pages 233-268) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. -------- Price 15 cents CONTENTS Page Introduction......................................................... 233 Acknowledgments...................................................... 234 Rainfall,............................................................ 235 Causes.......................................................... 235 General features................................................ 236 Rainfall records................................................ 237 Flood discharges..................................................... 246 General features................................................ 246 Field work...................................................... 249 Office preparation of field data................................ 250 Assumptions and computations.................................... 251 Flood-discharge records........................................ -

Schoharie Creek Biological Assessment, 2015

SCHOHARIE CREEK Biological Stream Assessment September 9, 2015 STREAM BIOMONITORING UNIT 425 Jordan Rd, Troy, NY 12180 P: (518) 285-5627 | F: (518) 285-5601 | [email protected] www.dec.ny.gov BIOLOGICAL STREAM ASSESSMENT Schoharie Creek Greene County, New York Mohawk River Drainage Basin Survey date: September 9, 2015 Report date: February 2, 2017 Elizabeth A. Mosher Alexander J. Smith Brian Duffy Diana L. Heitzman Jeff Lojpersberger Stream Biomonitoring Unit Bureau of Water Assessment and Management Division of Water NYS Department of Environmental Conservation Albany, New York www.dec.ny.gov For additional information regarding this report please contact: Alexander J. Smith, PhD New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Stream Biomonitoring Unit 425 Jordan Road, Troy, NY 12180 [email protected] ph 518-285-5627 fx 518-285-5601 Table of Contents Background ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Results and Conclusions ................................................................................................................. 1 Discussion ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Literature Cited ............................................................................................................................... 3 Figure 1. Overview mapons. .......................................................................................................... -

2007 Traffic Data Report for New York State

2007 TRAFFIC DATA REPORT FOR NEW YORK STATE New York State Department of Transportation Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Introduction.........................................................................................................1 Chapter 2: Traffic Data Collecting Program Overview........................................................2 Chapter 3: Accuracy of Traffic Data Section 3.1 Data Collection Equipment Requirements.............................................3 Section 3.2 Data Quality Control Checks.................................................................4 Chapter 4: Continuous Count Program Section 4.1 Introduction............................................................................................7 Section 4.2 Maps of Continuous Count Sites by Region..........................................8 Section 4.3 Map of High Speed Weigh-In-Motion Sites, Statewide .......................19 Section 4.4 Traffic Monitoring Site Details and Specifications ..............................20 Chapter 5: Coverage Count Program Section 5.1 Volume, Speed and Classification Counts............................................21 Section 5.2 Highway Performance Monitoring System ..........................................24 Section 5.3 Annual Traffic Monitoring Workshop..................................................24 Section 5.4 Mobile Traffic Monitoring Platforms ...................................................25 Section 5.5 County Counter Initiative .....................................................................26 -

Eastern NY Excluding Long Island 2014

DISCONTINUED SURFACE-WATER DISCHARGE OR STAGE-ONLY STATIONS The following continuous-record surface-water discharge or stage-only stations (gaging stations) in eastern New York excluding Long Island have been discontinued. Daily streamflow or stage records were collected and published for the period of record, expressed in water years, shown for each station. Those stations with an asterisk (*) before the station number are currently operated as crest-stage partial-record station and those with a double asterisk (**) after the station name had revisions published after the site was discontinued. [Letters after station name designate type of data collected: (d) discharge, (e) elevation, (g) gage height] Period of Station Drainage record Station name number area (mi2) (water years) HOUSATONIC RIVER BASIN Tenmile River near Wassaic, NY (d) 01199420 120 1959-61 Swamp River near Dover Plains, NY (d) 01199490 46.6 1961-68 Tenmile River at Dover Plains, NY (d) 01199500 189 1901-04 BLIND BROOK BASIN Blind Brook at Rye, NY (d) 01300000 8.86 1944-89 BEAVER SWAMP BROOK BASIN Beaver Swamp Brook at Mamaroneck, NY (d) 01300500 4.42 1944-89 MAMARONECK RIVER BASIN Mamaroneck River at Mamaroneck, NY (d) 01301000 23.1 1944-89 HUTCHINSON RIVER BASIN Hutchinson River at Pelham, NY (d) 01301500 6.04 1944-89 BRONX RIVER BASIN Bronx River at Bronxville, NY (d) 01302000 26.5 1944-89 HUDSON RIVER BASIN Opalescent River near Tahawus, NY (d) 01311900 9.02 1921-23 Arbutus Pond Outlet near Newcomb, NY (d) *01311992 1.22 1991-92 Cedar River near Indian Lake, NY (d) -

Environmental Goals and Infrastructure Realities: Transportation Dilemmas and Solutions"

ISSN 1052-7524 Proceedings of the Transportation Research Forum Volume 7 1993 35th TRF Annual Forum New York, New York October 14-16, 1993 The Environment and Transportation Infrastructure 51 Environmental Goals and Infrastructure Realities: Transportation Dilemmas and Solutions" Scott E. Nadler, Moderator Assistant Vice President Consolidated Rail Corporation My name is Scott Nadler. I'm Assistant budget analyst fresh out of college, when Vice President ofEnvironmental Quality the wise old heads assured me that it with Conrail. was a lot more fun to be a budget was no money. The examiner when there distinction between a truism and a That didn't make a lot of sense. They cliche is that a truism is what you say said, sure it does. and a cliche is what somebody else says. Let me start with two truisms that I When there is no money, there are no think will be central to what we are here easy choices. Everybody has to deal to talk about today. One is that with some pain. Therefore, you don't everything connects to everything. I spend time convincing people to make t hought I had some sense of that. I painful decisions. It is only a question of l earned it a lot more poignantly in the which painful decision. Half the fight is Year-and-a-half that I've been managing a already fought for you. corporate environmental program. It is clear, though, that it is not a principle On the transportation side, that is the that has always been put thoroughly terms into world we are dealing in today.