Audit Reports Over the Years Showing the Authority MHA’S Failure to Provide Tenants with Decent, Safe, and Sanitary Housing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY2013/2014 Consolidated Results: the Group Maintains a High Level of Operating Margin (€57.7 Millions)

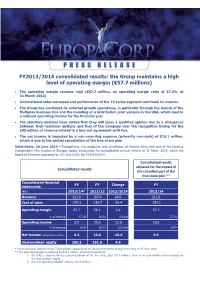

FY2013/2014 consolidated results: the Group maintains a high level of operating margin (€57.7 millions) The operating margin remains high (€57.7 million, an operating margin ratio of 27.3% at 31 March 2014) International sales increased and performance of the TV series segment continued to improve The Group has continued its external growth operations, in particular through the launch of the Multiplex business line and the founding of a distribution joint venture in the USA, which lead to a reduced operating income for the financial year The statutory auditors have stated that they will issue a qualified opinion due to a divergence between their technical analysis and that of the Company over the recognition timing for the $45 million of revenue related to a buy-out agreement with Fox. The net income is impacted by a non-recurring expense (primarily non-cash) of €10.1 million, which is due to the partial cancellation of the free share plan Saint-Denis, 26 June 2014 – EuropaCorp, the producer and distributor of feature films and one of the leading independent film studios in Europe, today announces its consolidated annual results at 31 March 2014, which the Board of Directors approved on 25 June 2014, for FY2013/2014. Consolidated results adjusted for the impact of Consolidated results the cancelled part of the free share plan ** Consolidated financial FY FY Change FY statements (€m) 2013/14* 2012/13 2013/2014 2013/14 Revenue 211.8 185.8 26.0 211,8 Cost of sales -154.1 -129.7 -24.4 -154.1 Operating margin 57.7 56.1 1.6 57.7 % of revenue -

Star Channels, July 5

JULY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com VAMP HUNTER Eight and a half years after the events of the Season 1 fi nale of NOS4A2, Charlie (Zachary Quinto) is at large, and Vic (Ashleigh Cummings) is still on his trail. The stakes have never been higher as Charlie targets Wayne (Jason David), the son of Vic and Lou (Jonathan Langdon). Airing Sunday, July 5, on AMC. COVID-19 UPDATES LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss the top issues facing our community, from their home to yours. olelo.org TUESDAY AT 8:30AM, WEDNESDAY AT 7PM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 590207_LiveAtTheLegislature_COVID-19_2_Main.indd 1 6/4/20 11:50 AM ON THE COVER | NOS4A2 Thirsty for more Season 2 of ‘NOS4A2’ for those big-screen adaptations. “NOS4A2,” Meanwhile, in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on the other hand, is perfect for the television a townie named Victoria “Vic” McQueen continues on AMC treatment. It’s been given a two-season-and- (Ashleigh Cummings, “The Goldfinch,” 2019) counting run on AMC, the network that’s been must come to terms with her own supernatu- By Rachel Jones home to mega-hits such as “Breaking Bad” and ral powers. She can find answers and missing TV Media “Mad Men.” things just by riding her bike across an old, The show’s title is ominously pronounced decrepit bridge called the Shorter Way. While he Season 1 finale of “NOS4A2” couldn’t “Nosferatu,” and its license plate-styled spell- crossing the bridge, Vic meets a medium have been more riveting: a maniacal im- ing is a nod to the book’s cover art and one of named Maggie (Jahkara Smith, “Into the Dark”), Tmortal woke up from his coma, ready to the story’s most important characters, a 1938 who gives her an important mission: save the feed on the souls of more children. -

The Phenomenological Aesthetics of the French Action Film

Les Sensations fortes: The phenomenological aesthetics of the French action film DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Alexander Roesch Graduate Program in French and Italian The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Flinn, Advisor Patrick Bray Dana Renga Copyrighted by Matthew Alexander Roesch 2017 Abstract This dissertation treats les sensations fortes, or “thrills”, that can be accessed through the experience of viewing a French action film. Throughout the last few decades, French cinema has produced an increasing number of “genre” films, a trend that is remarked by the appearance of more generic variety and the increased labeling of these films – as generic variety – in France. Regardless of the critical or even public support for these projects, these films engage in a spectatorial experience that is unique to the action genre. But how do these films accomplish their experiential phenomenology? Starting with the appearance of Luc Besson in the 1980s, and following with the increased hybrid mixing of the genre with other popular genres, as well as the recurrence of sequels in the 2000s and 2010s, action films portray a growing emphasis on the importance of the film experience and its relation to everyday life. Rather than being direct copies of Hollywood or Hong Kong action cinema, French films are uniquely sensational based on their spectacular visuals, their narrative tendencies, and their presentation of the corporeal form. Relying on a phenomenological examination of the action film filtered through the philosophical texts of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Paul Ricoeur, Mikel Dufrenne, and Jean- Luc Marion, in this dissertation I show that French action cinema is pre-eminently concerned with the thrill that comes from the experience, and less concerned with a ii political or ideological commentary on the state of French culture or cinema. -

Habitat Conservation Plan

San Antonio Water System Micron Pipeline and Water Resources Integration Program Habitat Conservation Plan Prepared for San Antonio Water System Prepared by SWCA Environmental Consultants SWCA Project Number 26461-AUS FINAL November 2017 SAN ANTONIO WATER SYSTEM MICRON PIPELINE AND WATER RESOURCES INTEGRATION PROGRAM HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN Prepared for San Antonio Water System 2800 U.S. Hwy 281 North San Antonio, Texas 78212 Attn: John Reynolds (210) 233-3299 Prepared by Amanda Aurora, C.W.B., Regional Scientist and Project Manager Jenna Cantwell, Environmental Specialist Marli Claytor, Environmental Specialist SWCA Environmental Consultants 4407 Monterey Oaks Boulevard Building 1, Suite 110 Austin, Texas 78749 (512) 476-0891 www.swca.com SWCA Project No. 26461 FINAL November 2017 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Description of the Proposed Projects ............................................................................. 8 Water Resources Integration Program .................................................................... 8 Micron Pipeline ................................................................................................. 10 1.2 Purpose and Need for the Proposed Projects ............................................................... 13 1.3 Regulatory Context ................................................................................................... 13 1.4 Karst Invertebrate Discoveries -

Liste Alphabétique Des DVD Du Club Vidéo De La Bibliothèque

Liste alphabétique des DVD du club vidéo de la bibliothèque Merci à nos donateurs : Fonds de développement du collège Édouard-Montpetit (FDCEM) Librairie coopérative Édouard-Montpetit Formation continue – ÉNA Conseil de vie étudiante (CVE) – ÉNA septembre 2013 A 791.4372F251sd 2 fast 2 furious / directed by John Singleton A 791.4372 D487pd 2 Frogs dans l'Ouest [enregistrement vidéo] = 2 Frogs in the West / réalisation, Dany Papineau. A 791.4372 T845hd Les 3 p'tits cochons [enregistrement vidéo] = The 3 little pigs / réalisation, Patrick Huard . A 791.4372 F216asd Les 4 fantastiques et le surfer d'argent [enregistrement vidéo] = Fantastic 4. Rise of the silver surfer / réalisation, Tim Story. A 791.4372 Z587fd 007 Quantum [enregistrement vidéo] = Quantum of solace / réalisation, Marc Forster. A 791.4372 H911od 8 femmes [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, François Ozon. A 791.4372E34hd 8 Mile / directed by Curtis Hanson A 791.4372N714nd 9/11 / directed by James Hanlon, Gédéon Naudet, Jules Naudet A 791.4372 D619pd 10 1/2 [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Daniel Grou (Podz). A 791.4372O59bd 11'09''01-September 11 / produit par Alain Brigand A 791.4372T447wd 13 going on 30 / directed by Gary Winick A 791.4372 Q7fd 15 février 1839 [enregistrement vidéo] / scénario et réalisation, Pierre Falardeau. A 791.4372 S625dd 16 rues [enregistrement vidéo] = 16 blocks / réalisation, Richard Donner. A 791.4372D619sd 18 ans après / scénario et réalisation, Coline Serreau A 791.4372V784ed 20 h 17, rue Darling / scénario et réalisation, Bernard Émond A 791.4372T971gad 21 grams / directed by Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu ©Cégep Édouard-Montpetit – Bibliothèque de l’École nationale d'aérotechnique - Mise à jour : 30 septembre 2013 Page 1 A 791.4372 T971Ld 21 Jump Street [enregistrement vidéo] / réalisation, Phil Lord, Christopher Miller. -

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List

Hartford Public Library DVD Title List # 24 Season 1 (7 Discs) 2 Family Movies: Family Time: Adventures 24 Season 2 (7 Discs) of Gallant Bess & The Pied Piper of 24 Season 3 (7 Discs) Hamelin 24 Season 4 (7 Discs) 3:10 to Yuma 24 Season 5 (7 Discs) 30 Minutes or Less 24 Season 6 (7 Discs) 300 24 Season 7 (6 Discs) 3-Way 24 Season 8 (6 Discs) 4 Cult Horror Movies (2 Discs) 24: Redemption 2 Discs 4 Film Favorites: The Matrix Collection- 27 Dresses (4 Discs) 40 Year Old Virgin, The 4 Movies With Soul 50 Icons of Comedy 4 Peliculas! Accion Exploxiva VI (2 Discs) 150 Cartoon Classics (4 Discs) 400 Years of the Telescope 5 Action Movies A 5 Great Movies Rated G A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2 Discs) 5th Wave, The A.R.C.H.I.E. 6 Family Movies(2 Discs) Abduction 8 Family Movies (2 Discs) About Schmidt 8 Mile Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family Absolute Power 10 Minute Solution: Pilates Accountant, The 10 Movie Adventure Pack (2 Discs) Act of Valor 10,000 BC Action Films (2 Discs) 102 Minutes That Changed America Action Pack Volume 6 10th Kingdom, The (3 Discs) Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ Smarter 11:14 Brother, The 12 Angry Men Adventures in Babysitting 12 Years a Slave Adventures in Zambezia 13 Hours Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland, The 13 Towns of Huron County, The: A 150 Year Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Heritage Adventures of Mickey Matson and the 16 Blocks Copperhead Treasure, The 17th Annual Lane Automotive Car Show Adventures of Milo and Otis, The 2005 Adventures of Pepper & Paula, The 20 Movie -

{FREE} Taken In

TAKEN IN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elizabeth Lynn Casey | 290 pages | 05 Aug 2014 | Berkley Books | 9780425257852 | English | New York, United States Taken () - IMDb Sam Jon Gries Casey David Warshofsky Bernie Holly Valance Sheerah Katie Cassidy Amanda Xander Berkeley Stuart Olivier Rabourdin St- Clair Famke Janssen Lenore Marc Amyot Pharmacist Arben Bajraktaraj Marko Radivoje Bukvic Anton as Rasha Bukvic Mathieu Busson Edit Did You Know? Trivia Before any action takes place, Bryan already has scratches to the left side of his face, hinting at his "spare time" activities. But he speaks perfect northern Irish English throughout the scene. No one would have mistaken him for a Frenchman. Quotes [ first lines ] Singh : Mr. Mills, how are you? Bryan : I'm fine. How are you? Singh : Very fine. I suppose you want to see it again? Bryan : If you don't mind. Singh : You know where it is. Bryan : Oh yeah. Alternate Versions The distributor made minor changes to secure a 15 certificate for the UK theatrical release. The UK theatrical cut is the same as the International Cut except for the torture scene, which was replaced with the PG version to secure a 15 certificate. In the PG version, clamps are attached to the chair. In the International Cut, they're attached to spikes which are stabbed into the victim's legs. The uncut International Cut was released with an 18 certificate on video. This censored UK version was also released theatrically in Ireland with a 15A certificate. The extended torture scene didn't affect the certificate on video, and the uncut International Cut was also released with a 15 certificate in Ireland cinema and video certification systems are different in Ireland - a 15A at the cinema is equivalent to a 15 on video. -

D.B. Sweeney Theatrical Resume

D.B. Sweeney FILM THE MANSON BROTHERS MIDNIGHT ZOMBIE Supporting Mona Vista Productions Max Martini MASSACRE TWO DUM MICKS Lead Independent Feature D.B. Sweeney CAPTIVE STATE Supporting Dreamworks Rupert Wyatt DEAD ON ARRIVAL Lead Boatyard Productions Stephen C. Sepher HAYMAKER Lead Hood River Entertainment Nicholas Sasso THE RESURRECTION OF GAVIN STONE Lead Blumhouse Productions Dallas Jenkins CHI-RAQ Supporting Amazon Spike Lee HEIST Supporting EFO Films Scott Mann EXTRACTION Lead EFO Films Steven C. Miller K-11 Lead EFO Films Jules Stewart TAKEN 2 Supporting EuropaCorp Olivier Megaton MIRACLE AT ST. ANNA Lead Disney Spike Lee TWO TICKETS TO PARADISE Lead Scrudge LLC D.B. Sweeney HARDBALL Lead Paramount Pictures Brian Robbins SPAWN Lead McFarlane Films Mark Dippe ROOMMATES Lead Jeenyus Entertainment Peter Yates FIRE IN THE SKY Lead Paramount Pictures Rob Lieberman HEAR NO EVIL Lead 20th Century Fox Robert Greenwald THE CUTTING EDGE Lead MGM Paul Michael Glaser MEMPHIS BELLE Lead Enigma Productions Michael Cayton-Jones EIGHT MEN OUT Lead Orion Pictures John Sayles NO MAN'S LAND Lead Orion Pictures Peter Werner GARDENS OF STONE Lead MLD Premier Productions Francis Ford Coppola TELEVISION SHARP OBJECTS Recurring HBO Jean-Marc Vallee ICE Recurring Audience Network Edward Allen Bernero S.W.A.T. Guest Star CBS Billy Gierhart CONTROVERSY Guest Star FOX Glenn Ficarra JADED Lead Ton of Hats Christian Sesma MAJOR CRIMES Recurring TNT Various THE NIGHT SHIFT Guest Star NBC Eriq La Salle TO APPOMATTOX Recurring The Beckner Story Co. Mikael Salomon TWO AND A HALF MAN Recurring CBS Various THE LEGEND OF KORRA Recurring Nickelodeon Colin Heck BETRAYAL Recurring ABC Various TOUCH Recurring FOX Various VEGAS Guest Star CBS Anthony Hemingway THE CLOSER Guest Star TNT David McWhirter QUICKBITES Guest Star Acquaviva Productions Joe Mantegna CASTLE Guest Star ABC John Terlesky HAWAII FIVE-0 Guest Star CBS Matt Earl Beesley BRAIN TRUST Series Regular TBS Dean Devlin THE EVENT Recurring NBC Various THREE RIVERS Guest Star CBS Jeff T. -

Free Taken 2 Movie

Free taken 2 movie click here to download English subtitle. Watch online free Taken 2, Liam Neeson, Famke Janssen, Maggie Grace. Get updated once this movie is available in HD. Subscribe now. Watch Taken 2 Online For Free On moviesfree, Stream Taken 2 Online, Taken 2 Full Movies Free. Taken 2 Bryan Mills is the bodyguard for the famous people. During a trip to Istanbul, Bryan has invited his ex-wife Lenore and her daughter Kim to travel along. Watch Taken 2 Online - Free Streaming Taken Full Movie on Putlocker. Bryan is extremely clever. He does not need each of the gadgets and gizmos that. The retired CIA agent Bryan Mills invites his teenage daughter Kim and his exwife Lenore who has separated from her second husband to spend a couple of. Watch taken 2 movies Online. Watch taken 2 movies online for free on www.doorway.ru Taken 2 Liam Neeson returns as Bryan Mills, the retired CIA agent who vows to do Kim is luckily escape and in turn support her father to get them all free. Watch Taken 2 Online | taken 2 | Taken 2 () | Director: Olivier Megaton | Cast: YOU ARE WATCHING. Taken 2: Bryan Mills is the bodyguard for the famous people. Watch Taken 2 online Taken 2 Free movie. Taken 2 ##:Taken 2 ++++++++++++([ ])++++++++++++ #:~Taken 2 FuLL'MoViE'-'fRee'HD #:~Taken 2 FuLL. Watch Online Taken 2 HD, watch free Taken 2 Full Movie Streaming, Free Streaming EuroPix Taken 2 Online free movies hd Sa prevodom Full Movie with eng. Watch Taken 2 online. Free movie Taken 2 with English Subtitles. -

Gender Diffrences in the Movie “Taken 2”

GENDER DIFFRENCES IN THE MOVIE “TAKEN 2” A THESIS BY ENDA FITRIA SEMBIRING REG. NO. 140705003 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA GENDER DIFFERENCES IN THE MOVIE “TAKEN 2” A THESIS BY ENDA FITRIA SEMBIRING REG. NO. 140705003 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dra. Roma Ayuni A Loebis MA Ely Hayati Nasution, S.S, M.Si NIP. 196801221998032001 NIP. 198507032017062001 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from Department of English DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof. T. Silvana Sinar, M.A.,Ph.D Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D NIP. 19540916 198003 2 003 NIP. 19750209 200812 1 002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara, Medan. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on January 16, 2019 Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Prof. T. Silvana Sinar, M.A., Ph.D. ___________________ Dra. Roma Ayuni A Loebis, MA __________________ Dr. Drs Ridwan Hanafiah, SH., MA __________________ UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I, ENDA FITRIA SEMBIRING DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. -

RAI CINEMA Un Film Di MARTIN SCORSESE ANDREW GARFIELD

RAI CINEMA presenta un film di MARTIN SCORSESE con ANDREW GARFIELD ADAM DRIVER LIAM NEESON Un'esclusiva per l'Italia Rai Cinema Durata: 161’ Uscita: 12 gennaio 2017 Distribuzione 01 Distribution Ufficio stampa film 01 Distribution – Comunicazione Studio Lucherini Pignatelli P.za Adriana,12 – 00193 Roma Via A. Secchi, 8 – 00197 Roma Tel. 06 33179601 Tel. 06/8084282 Fax: 06/80691712 Annalisa Paolicchi: [email protected] [email protected] Rebecca Roviglioni: [email protected] www.studiolucherinipignatelli.it Cristiana Trotta: [email protected] I materiali sono disponibili sui siti www.studiolucherinipignatelli.it e www.01distribution.it Media partner: Rai Cinema Channel (www.raicinemachannel.it) CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI 1 Cast Artistico padre Sebastian Rodrigues ANDREW GARFIELD padre Francisco Garupe ADAM DRIVER padre Chistovao Ferreira LIAM NEESON Interpreter TADANOBU ASANO padre Valignano CIARÁN HINDS Vecchio Samurai/Inoue ISSEI OGATA Mokichi SHIN'YA TSUKAMOTO Ichizo YOSHI OIDA Kichijiro YÔSUKE KUBOZUKA 2 Cast Tecnico Regia MARTIN SCORSESE Sceneggiatura JAY COKS MARTIN SCORSESE Dall’omonimo Romanzo Di SHÛSAKU ENDÔ Direttore Della Fotografia RODRIGO PRIETO Scenografie DANTE FERRETTI Costumi DANTE FERRETTI Montaggio THELMA SCHOONMAKER Musiche KIM ALLEN KLUGE KATHRYN KLUGE Produttori MARTIN SCORSESE EMMA KOSKOFF IRWIN WINKLER RANDALL EMMETT BARBARA DE FINA GASTÓN PAVLOVICH VITTORIO CECCHI GORI Produttori Esecutivi DALE A. BROWN MATTHEW J. MALEK MANU GARGI KEN KAO DAN KAO NIELS JUUL CHAD A. VERDI GIANNI NUNNARI LEN BLAVATNIK AVIV GILADI Una Produzione IM GLOBAL Un’Esclusiva Per l’Italia RAI CINEMA 3 La Produzione Silence, l’attesissimo film sulla fede e la religione del regista premio Oscar Martin Scorsese, racconta la storia di due missionari portoghesi che nel XVII secolo intraprendono un lungo viaggio irto di pericoli per raggiungere il Giappone, alla ricerca del loro mentore scomparso, padre Christovao Ferreira, e per diffondere il cristianesimo. -

Audience Profile What Factors Attract an Audience to the Film?

TYPICAL AUDIENCE MEMBER OF THIS FILM AUDIENCE PROFILE WHAT FACTORS ATTRACT AN AUDIENCE TO THE FILM? AGE: 20-50 GENRE(S): The rating (18) leads us to believe that this film is Action, Thriller, there is also an element of crime intended for an adult audience but the younger but the film is based on personal revenge instead of generation would find this appealing due to the police intervention. dark themes. STORY: GENDER: Male The story centres on a young girl who gets taken for The protagonist is male and dominates the proxe- sexual trafficking. Her fathers hunts these men mics of the poster. This is influential to the audi- down and strives to protect his daughter through ence because he holds a gun, signifying violence sinful crimes, corruption and death. and action. STAR/DIRECTOR: VALUES & BELIEFS: Liam Neeson features in many award winning thriller A level of crime in order to protect his daughter, films, which instantly draws thriller fanatics. His appear- this due to his paternal instincts. The obvious ance is typical for a protagonist within the genre. Pierre use of the firearms suggests his nature and mor- Morel is a French director, most commonly know for al values. thrillers such as Taken, The Transporter and The Trans- porter 2. He typically works in the action/thriller genre MEDIA CONSUMPTION: and is widely recognised. A general thriller enthusiast would likely be drawn into Taken as it’s typical of a thriller film. ‘WOW’ FACTOR: They might also enjoy action films as this thriller Liam Neeson is well know for action films and their well is obviously violent due to the firearm.