Proposed Second Amended Complaint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DELAWARE RIVER WATERSHED STREAMBANK EROSION ASSESSMENT Arcgis® Comparison Study: 1991, 2002, 2003 Vs

DELAWARE RIVER WATERSHED STREAMBANK EROSION ASSESSMENT ArcGIS® Comparison Study: 1991, 2002, 2003 vs. 2015 Aerial Photography UPDATED DRAFT: April 2017 Prepared by: Kansas Water Office 900 SW Jackson Street, Suite 404, Topeka, KS 66612 (785) 296-3185, www.kwo.org Table of Contents Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 3 Study Area……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Figure 1: Delaware River Watershed Assessment Area…………………………………………………. 5 Data Collection Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Figure 2: 2002 FSA & 2015 NAIP of a Streambank Erosion Site on the Delaware River……………… 6 Analysis…………………………………………………………………………………………………………... 7 Figure 3: Delaware River Watershed Assessment Area HUC10s……………………………………….. 8 Figure 4: Delaware River Watershed Assessment Area HUC12s……………………………………….. 9 Table 1: TWI Estimated Costs to Implement Streambank Stabilization BMPs………………………... 10 Results………………………………………………………………………………………………………....... 10 Table 2: Delaware River Watershed Streambank Erosion Assessment Table by HUC10....................... 11 Figure 5: Delaware River Watershed Streambank Erosion Assessment Graph by HUC10..................... 11 Table 3: Delaware River Watershed Streambank Erosion Assessment Table by HUC12....................... 12 Figure 6: Delaware River Watershed Streambank Erosion Assessment Graph by HUC12..................... 13 Conclusion........................................................................................................................................................... -

Soil Survey of Brown County, Kansas

United States In cooperation with Department of Kansas Agricultural Agriculture Experiment Station Soil Survey of Brown County, Natural Kansas Resources Conservation Service i How To Use This Soil Survey Detailed Soil Maps The detailed soil maps can be useful in planning the use and management of small areas. To find information about your area of interest, locate that area on the Index to Map Sheets. Note the number of the map sheet and turn to that sheet. Locate your area of interest on the map sheet. Note the map unit symbols that are in that area. Turn to the Contents, which lists the map units by symbol and name and shows the page where each map unit is described. The Contents shows which table has data on a specific land use for each detailed soil map unit. Also see the Contents for sections of this publication that may address your specific needs. ii This soil survey is a publication of the National Cooperative Soil Survey, a joint effort of the United States Department of Agriculture and other Federal agencies, State agencies including the Agricultural Experiment Stations, and local agencies. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service) has leadership for the Federal part of the National Cooperative Soil Survey. Major fieldwork for this soil survey was completed in 1992. Soil names and descriptions were approved in 1994. Unless otherwise indicated, statements in this publication refer to conditions in the survey area in 1994. This survey was made cooperatively by the Natural Resources Conservation Service and the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station. -

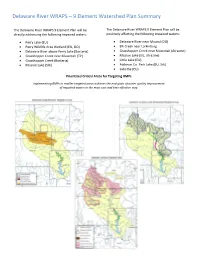

Delaware River WRAPS – 9 Element Watershed Plan Summary

Delaware River WRAPS – 9 Element Watershed Plan Summary The Delaware River WRAPS 9 Element Plan will be The Delaware River WRAPS 9 Element Plan will be directly addressing the following impaired waters: positively affecting the following impaired waters: • Perry Lake (EU) • Delaware River near Mound (DO) • Perry Wildlife Area Wetland (EU, DO) • Elk Creek near Larkinburg • Delaware River above Perry Lake (Bacteria) • Grasshopper Creek near Muscotah (Atrazine) • Grasshopper Creek near Muscotah (TP) • Mission Lake (EU, Atrazine) • Grasshopper Creek (Bacteria) • Little Lake (EU) • Mission Lake (Silt) • Atchison Co. Park Lake (EU, Silt) • Sabetha (EU) Prioritized Critical Areas for Targeting BMPs Implementing BMPs in smaller targeted areas achieves th e end goals of water quality improvement of impaired waters in the most cost and time effective way. Delaware River WRAPS – 9 Element Watershed Plan Summary Targeting Considerations: • Cropland Targeted areas were identified after reviewing a SWAT model and a KDHE Cropland/Slope analysis. Landowner knowledge was also considered. • Livestock Targeted areas were identified after landowners in the watershed determined which areas had the largest number of uncertified animal operations. • Streambank targeted areas where identified based on several studies including the TWI 2008 stream channel morphology and a 2007 Geological Survey study . • Gully targeted areas where identified by a 2010 KWO study of gully erosion sites using GIS layers. Best Management Practices and Load Reduction Goal Cropland -

Delaware River Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy

Delaware River Watershed Restoration And Protection Strategy May 2007 DELAWARE RIVER WATERSHED RESTORATION AND PROTECTION STRATEGY By Marlene K. Bosworth Delaware River WRAPS Coordinator April 2007 2 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Delaware River Watershed Restoration and Protection Strategy (WRAPS) is to provide the framework for the implementation of water quality improvement practices and behaviors through technical, informational, educational and financial assistance to stakeholders in the watershed. Our goal is to restore the watershed to a condition with clean water, healthy habitats and open spaces for human and wildlife communities. We aim to make the watershed a place where people work together to sustain mutual economic and environmental well-being. ¾ WRAPS is a “community-based” watershed management project, with the “community” being the Delaware River Watershed. Its goal is to protect and restore watershed functions while considering the social and economic factors of the human and non-human residents of the community and the benefits of those watershed functions to each. ¾ Everyone lives in a watershed and is part of a watershed community. The actions of individuals can have a positive or a negative impact on the health of natural resources (the soil, water, air, plants and animals) in their watershed. Small watersheds join together to form larger watersheds, much like many branches on a tree together form the whole tree. What happens in individual, smaller watersheds affects larger watersheds downstream. A WATERSHED is the area that water flows across or under on its way to a particular stream, river, lake or ocean. The DELAWARE RIVER WATERSHED is the area that water flows across or under on its way to the Delaware River in northeast Kansas, an area of over 1,110 square miles. -

S If-,I "<>Msid3y

JUV:i IVNOliVN S30 : s if-,i "<>msiD3y 1VN United States Department of the Interior National Park Service -- H 6 HW National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 0822 (JdAGOBd 1. Name of Property Historic name: other name/site number: Delaware River Composite Truss Bridge (preferred): 44-HT-03 2. location On Coal Creek Road. 0.1 miles south of the intersection with 170th Road: at the northeast city limits of Valley Falls.__________________________________________________ not for publication city or town Valley Falls X vicinity state code KS county Jefferson county code 087 zip code 66088 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally ^stat^wide __ locally. ( __ J=>ee continuation sheet for additional comments. Signature of certifying official Date State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria. See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. :ional Park Service Certification I, pereby, certify that this property entered in the National Register. __ See continuation sheet __ determined eligible for the National See continuation sheet determined not eligible for the National Register, removed from the National Register.____________ other, ( explain: ) _________________________ ignature of Keeper Date of Action NPS form 10-900 0MB Jto. -

109 W. Fourth Street, Holton, KS 66436 in the Classifieds

SAVINGS SALUTE THE HOLTON When you subscribe , MAYETTA, KANSAS you save nearly 50% Hometown of off the newsstand price! Rosalie Walrod Holton Recorder subscriber for 30 years. RECORDERSerin te acson ounty ounity for years Volume 150, Issue 49 HOLTON, KANSAS • Wednesday, June 21, 2017 14 Pages $1.00 July Budget Jubilee time planned nears By Brian Sanders By Ali Holcomb Budget proposals for fiscal July Jubilee is planned for year 2018 in the City of Holton’s Saturday, July 1, at Banner water and wastewater, electrical Creek Reservoir, and the annual produc tion and electrical distri event will feature music, ven- bution de partments were heard dors, activities for children and on Monday by the Holton City a large fireworks display by 2 Commission, which noted that Kirks Fireworks. those three de partments were Sponsored by the Holton/ “holding the line” on their bud Jackson County Chamber of th get requests. Commerce, the 11 -annual event During the commission’s reg kicks off at 5 p.m. that day with ular meeting on Monday, Water craft and product vendors on the and Wastewater Superintendent north side of the reservoir, ac- Dennis Ashcraft, Electrical Dis cording to Lori Banks, Chamber tribution Superintendent Scott director. Frederick and Electrical Pro A free will donation dinner duction Superinten dent Ira Har of hamburgers, hot dogs, chips rison met with com missioners and a drink will be served by the to discuss their departments’ Chamber with the meat donated budget requests for FY 2018, by Holton Meat Processing. compared with their budgets for Several bounce houses will be 2016 and 2017. -

Needs Assessment

SUMMARY Final Draft Water Needs Assessment Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Sac and Fox Nation of Missouri u.s. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center Denver, Colorado October 2002 SUMMARY Final Draft Water Needs Assessment Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Sac and Fox Nation of Missouri u.s. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Technical Service Center Denver, Colorado October 2002 Contents Page • "The Great American Desert" .................................... S-1 • Water is still scarce ............................................. S-1 • More specifically ............................................... S-3 On the Kickapoo Reservation . .. S-4 On the Potawatomi Reservation ................................. S-5 On the Sac and Fox Reservation . .. S-5 • Water needs are growing ......................................... S-7 • Storage needs also exist ..... .. S-8 • Self-determination and development ... .. S-9 Kickapoo Reservation . .. S-10 Potawatomi Reservation ...................................... S-lO Sac and Fox Reservation . .. S-11 • Overall . .. S-12 • Reclamation's role ............................................. S-12 • Possibilities (and some potential problems) ......................... S-13 Kickapoo Tribe in Kansas ..................................... S-13 Groundwater ............................................. S-13 Surface water. .. S-13 Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation ................................ S-13 Groundwater ............................................ -

1561 7874. Another Guthrie Pioneer Passed Over at 8:10 O'clock Monday

7874. Another Guthrie pioneer passed over at 8:10 o’clock Monday morning when death called Eber L. Brown, for eighteen years a resident, and for fifteen years actively identified with the business interests of the city. The deceased had been a sufferer from Bright's disease the past two years. He was born in Illinois and raised in Kansas and came here in the early days from Holton, Kansas. He lived on a farm near the city for two years and then moved to town .... He was 67 years of age and an ardent member of the Odd fellow's lodge. The deceased leaves a wife and five children: Mrs. J. A. McElhinney, of Guthrie, Mrs. J. H. McElhinney, of Arkansas City; Mrs. Al Hough, of Winfield; Miss Lillian Brown, and Frank Brown of Ft. Smith, engineer on the Fort Smith & Western .... in charge of the I.O.O.F lodge ... the burial will be in Sunmit View .... Guthrie Daily. Mr. Brown was a brother of Chas. and Zara Brown of this city, and located at Ontario this county with his parents in 1859 and resided there until 1891. He has a brother still living there, Milton A. Brown. The Holton Recorder, January 4, 1912. .... The body was interred in the cemetery at Ontario. The Holton Recorder, December 21, 1911. Nancy E. Rounsaville was born August 31, 1834, in Indiana, and died at the home of her daughter in Guthrie, Okla., Feb. 26, 1912, aged 77 years, 6 months and 26 days. Her parents moved to Illinois while she was a child. -

Selected Death Notices from Jackson County, Kansas

SELECTED DEATH NOTICES FROM JACKSON COUNTY, KANSAS, NEWSPAPERS VOLUME IV 1897-1899 COMPILED BY DAN FENTON 2002 ii INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the time period covered by this volume, there were six newspapers being published in Holton, The Holton Weekly Recorder, The Holton Weekly Signal, Normal Advocate, University Informer, The Tribune, and The Kansas Sunflower. The University Informer ceased publication June 1898, and the Normal Advocate, in March 1899. Both were publications of Campbell University. The Soldier Clipper, and the Circleville News, continued in their respective cities. In Whiting, the Sun ceased its publication January 28, 1898, but the Whiting Journal newspaper soon replaced it on February 18, 1898. In Netawaka, the Netawaka Herald ceased publication on June 30, 1899. In Denison, the Hummer began publication on January 10, 1899, and ceased March 15, 1899. As noted in the previous volumes, not every death reported in these newspapers is included in this book, only those seeming to have some connection with Jackson county. A death notice could appear in different newspapers and from different sources within a paper. One principal notice is listed with excerpts from other accounts being used only when there is differing or additional information. Accolades to the deceased success as a Christian, parent and citizen have been deleted when possible, because of space consideration. Three ellipses denote the deletion of part of a sentence and four that of a sentence or even paragraphs. Each death notice is numbered consecutively and it is this number that appears in the index, not the page number. This is an all surname index that I hope will help the researcher identify family relationships that otherwise would be hidden. -

Delaware River Watershed Above Perry Lake Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus

KANSAS-LOWER REPUBLICAN BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody / Assessment Unit: Delaware River Watershed above Perry Lake Water Quality Impairment: Total Phosphorus 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Delaware River Counties Atchison, Brown, Jackson, Jefferson, Nemaha HUC 8: 10270103 HUC10 (HUC12): 01 (01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, 07, 08, 09, 10) 02 (01, 02, 03, 04, 05) 03 (01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, 07, 08) 04 (01, 08) Ecoregion: Loess and Glacial Drift Hills (47i) Drainage Area: Approximately 741.1 square miles Main Stem Water Quality Limited Segments: Water Quality Limited Segments Covered Under this TMDL (designated uses for main stem and tributary segments are detailed in Table 1): Station Main Stem Segment Tributaries SC554 Delaware R (13) Nebo Cr (48) Catamount Cr (49) Delaware R (14) Delaware R (15) Little Grasshopper Cr (16) Negro Cr (43) Delaware R (17) Gregg Cr (24) Muddy Cr (25) Muddy Cr (26) Wolfley Cr (27) Plum Cr (36) Cedar Cr (37) Squaw Cr (38) Barnes Cr (39) Delaware R (21) Delaware R (22) Delaware R (23) SC603 Grasshopper Cr (18) Clear Cr (19) Brush Cr (44) Mission Cr (40) Otter Cr (41) Grasshopper Cr (20) 1 SC604 Elk Cr (29) Unnamed Stream (31) Banner Cr (45) Bills Cr (47) Elk Cr (30) SC686 Straight Cr (28) Spring Cr (42) Mosquito Cr (602) Table 1. Designated uses for main stem and tributary segments in the watershed (Kansas Department of Health and Environment, 2013). Stream Segment Expected Contact Domestic Food Ground Industrial Irrigation Livestock # Aquatic Recreation Supply Procurement Water Water -

1903-1905 (Pdf)

SELECTED DEATH NOTICE FROM JACKSON COUNTY, K ANSAS, NEWSPAPERS VOLUME VI 1903-1905 COMPILED BY DAN FENTON SELECTED DEATH NOTICES FROM JACKSON COUNTY, KANSAS, NEWSPAPERS VOLUME VI 1903-1905 COMPILED BY DAN FENTON 2004 ii INTRODUCTION At the beginning of the time period covered by this volume, there were four newspapers being published in Holton, The Holton Weekly Recorder, The Holton Weekly Signal, The Tribune, and The Kansas Sunflower. The Holton Weekly Signal continued publication through this time period The Holton Weekly Recorder and The Tribune merged and was called The Recorder-Tribune. The Kansas Sunflower ceased publication on March 10, 1.904. The short-lived Holton Sunbeam began on April 9. 1904 and ceased publication on August 17, 1904. The Soldier Clipper, Whiting Journal , and the Hoyt Sentinel, continued in their respective cities. In Circleville the Jackson County World, continued its publication. The Denison Herald barely made it past the New Year, ceasing publication on January 29, 1903. The Netawaka Times started up on October 15, 1903 and folded on November 17, 1904. The Mayetta News was also short-lived, being published from July 20, 1904 through February 24, 1905 As noted in the previous volumes, not every death reported in these newspapers is included in this book, only those seeming to have some connection with Jackson county. A death notice could appear in different newspapers and from different sources within a paper. One principal notice is listed with excerpts from other accounts being used only when there is differing or additional information. Accolades to the deceased success as a Christian, parent and citizen have been deleted when possible, because of space consideration. -

Jefferson County, Kansas

Jefferson County, Kansas COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Adopted on March 27, 2001, by: The Jefferson County Planning Commission In Association with: The Plan Update Steering Committee Consultant Team: Bucher, Willis & Ratliff Corporation In Association with: Richard Caplan & Associates Price Banks & Associates Tom Daniels, Ph.D. JEFFERSON COUNTY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN County Courthouse 300 Jefferson Street P.O. Box 628 Oskaloosa, KS 66066 COUNTY COMMISSIONERS George Mathews, Chairman Francis Grollmes Travis Oliver PLANNING COMMISSION Patrick Reed, Chairman Shirley Strickler, Vice-Chairman Bret Frakes, Secretary Darrell Hammond David Hemme Robb Hensleigh Glen Wear PLAN STEERING COMMITTEE Robert Abel, Sr. Kevin Kuenzi Bob Best Rick Link Robert Bigham Richard Malm Eric Bowser Jim Marietta Candy B raksick Mary Prewitt Terry Burris John Purvis Bob Clark Bill Reed Larry Cope Bill Rhodes Jim Craig Tom Ryan Charles Domann Charles Sedlock Charles Hamon Scott Slava Don Haynes Ruth Sneegas Joe Heinen Fred Sobering Steve Hughes Terry Sullivan Merrill Jacob Dave Taylor Paul Johnson Meril Vanderpool Ron Karn Jeff Van Petten COUNTY STAFF CONSULTANT June Huston, Planning/Zoning Administrator Bucher, Willis, Ratliff Corporation Eloise Tichenor, Administrative Assistant 7920 Ward Parkway Debbie Kruse, PT Clerk Kansas City, MO 64114 (816) 363-2696 GIS COORDINATOR SUB CONSULTANTS Chris Schmeissner, Ph.D. Richard Caplan and Associates, Lawrence, KS Price Banks and Associates, Lawrence, KS Tom Daniels, Ph.D., Albany, New York JEFFERSON COUNTY, KANSAS Table of Contents TABLE