Alist of Background Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soho Action Plan: Your Thoughts in Action

Soho Action Plan: Your thoughts in action One Soho Soho is a unique part of the t it has an international identity as a cros ities and energy of the people who live an Without order we cannot live in, work in, o pleasant experience and we will work with ense of belonging and a wide range of op e of the most exciting and colourful part uraging diversity in retail and protecting up dialogue between businesses and re he foundations for enterprise in Soho. Re e look after the heart of this city. We propo neration, and we will improve the public re Contents 1 Introduction 3 Foreword 7 One Soho 13 Order 21 Opportunity 27 Enterprise 35 Renewal: Our lasting legacy 41 One Soho, One City, One Action Plan 45 List of actions 52 Contact details capital that has grown out of a rich s-cutting and cosmopolitan melting nd work here, which makes this area or visit Soho in enjoyment and peace. h the police and the Soho community pportunities in Soho that make even ts of the capital, if not the world, in Soho’s core businesses, promoting esidents, making the council more enewal: Our lasting legacy We will be ose real consultation with residents, ealm to make Soho accessible to all. Soho Boundary Soho is the area within the boundaries set by Oxford Street, Regent Street, Shaftesbury Avenue, and Charing Cross Road (for the purpose of this Action Plan). Featured Imagery 1 KINGLY COURT 2 SOHO HOTEL 3 SOHO SQUARE TOTTENHAM 4 MEARD STREET COURT ROAD 5 BERWICK STREET MARKET 6 GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET 19 20 18 GREA OXFORD STREET TCH W CH TON RO Additional Streets -

Character Overview Westminster Has 56 Designated Conservation Areas

Westminster’s Conservation Areas - Character Overview Westminster has 56 designated conservation areas which cover over 76% of the City. These cover a diverse range of townscapes from all periods of the City’s development and their distinctive character reflects Westminster’s differing roles at the heart of national life and government, as a business and commercial centre, and as home to diverse residential communities. A significant number are more residential areas often dominated by Georgian and Victorian terraced housing but there are also conservation areas which are focused on enclaves of later housing development, including innovative post-war housing estates. Some of the conservation areas in south Westminster are dominated by government and institutional uses and in mixed central areas such as Soho and Marylebone, it is the historic layout and the dense urban character combined with the mix of uses which creates distinctive local character. Despite its dense urban character, however, more than a third of the City is open space and our Royal Parks are also designated conservation areas. Many of Westminster’s conservation areas have a high proportion of listed buildings and some contain townscape of more than local significance. Below provides a brief summary overview of the character of each of these areas and their designation dates. The conservation area audits and other documentation listed should be referred to for more detail on individual areas. 1. Adelphi The Adelphi takes its name from the 18th Century development of residential terraces by the Adam brothers and is located immediately to the south of the Strand. The southern boundary of the conservation area is the former shoreline of the Thames. -

Download Brochure

A JEWEL IN ST JOHN’S WOOD Perfectly positioned and beautifully designed, The Compton is one of Regal London’ finest new developments. ONE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this LUXURIOUSLY image APPOINTED APARTMENTS SET IN THE GRAND AND TRANQUIL VILLAGE OF ST JOHN’S WOOD, LONDON. With one of London’s most prestigious postcodes, The Compton is an exclusive collection of apartments and penthouses, designed in collaboration with world famous interior designer Kelly Hoppen. TWO THREE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this image FOUR FIVE ST JOHN’S WOOD CULTURAL, HISTORICAL AND TRANQUIL A magnificent and serene village set in the heart of London, St John’s Wood is one of the capital’s most desirable residential locations. With an attractive high street filled with chic boutiques, charming cafés and bustling bars, there is never a reason to leave. Situated minutes from the stunning Regent’s Park and two short stops from Bond Street, St John’s Wood is impeccably located. SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE CHARMING LOCAL EATERIES AND CAFÉS St John’s Wood boasts an array of eating and drinking establishments. From cosy English pubs, such as the celebrated Salt House, with fabulous food and ambience, to the many exceptional restaurants serving cuisine from around the world, all tastes are satisfied. TEN TWELVE THIRTEEN BREATH TAKING OPEN SPACES There are an abundance of open spaces to enjoy nearby, including the magnificent Primrose Hill, with spectacular views spanning across the city, perfect for picnics, keeping fit and long strolls. -

Carnaby History

A / W 1 1 Contents Introduction C S W T S C A RN A BY IS KNO W N FOR UNIQUE INDEPENDENT BOUTIQUES , C ON C EPT STORES , GLOBA L FA SHION C F & D N Q BR A NDS , awa RD W INNING RESTAUR A NTS , ca FÉS A ND BA RS ; M A KING IT ONE OF L ONDON ' S MOST H POPUL A R A ND DISTIN C TIVE SHOPPING A ND LIFESTYLE DESTIN ATIONS . T K C S TEP UNDER THE IC ONIC C A RN A BY A R C H A ND F IND OUT MORE A BOUT THE L ATEST EXPERIEN C E THE C RE ATIVE A ND UNIQUE VIBE . C OLLE C TIONS , EVENTS , NE W STORES , T HE STREETS TH AT M A KE UP THIS STYLE VILL AGE RESTAUR A NTS A ND POP - UP SHOPS AT I F’ P IN C LUDE C A RN A BY S TREET , N E W BURGH S TREET , ca RN A BY . C O . UK . M A RSH A LL S TREET , G A NTON S TREET , K INGLY S TREET , M F OUBERT ’ S P L ac E , B E A K S TREET , B ROA D W IC K S TREET , M A RLBOROUGH C OURT , L O W NDES C OURT , G RE AT M A RLBOROUGH S TREET , L EXINGTON S TREET A ND THE VIBR A NT OPEN A IR C OURTYA RD , K INGLY C OURT . C A RN A BY IS LO caTED JUST MINUTES awaY FROM O XFORD C IR C US A ND P Icca DILLY C IR C US IN THE C ENTRE OF L ONDON ’ S W EST E ND . -

Rare Long-Let Freehold Investment Opportunity INVESTMENT SUMMARY

26 DEAN STREET LONDON W1 Rare Long-Let Freehold Investment Opportunity INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Freehold. • Prominently positioned restaurant and ancillary building fronting Dean Street, one of Soho’s premier addresses. • Soho is renowned for being London’s most vibrant and dynamic sub-market in the West End due to its unrivalled amenity provisions and evolutionary nature. • Restaurant and ancillary accommodation totalling 2,325 sq ft (216.1 sq m) arranged over basement, ground and three uppers floors. • Single let to Leoni’s Quo Vadis Limited until 25 December 2034 (14.1 years to expiry). • Home to Quo Vadis, a historic Soho private members club and restaurant, founded almost a 100 years ago. • Restaurant t/a Barrafina’s flagship London restaurant, which has retained its Michelin star since awarded in 2013. • Total passing rent £77,100 per annum, which reflects an average rent of £33.16 per sq ft. • Next open market rent review December 2020. • No VAT applicable. Offers are invited in excess of £2,325,000 (Two Million Three Hundred and Twenty-Five Thousand Pounds), subject to contract. Pricing at this level reflects a net initial yield of 3.12% (after allowing for purchaser’s costs of 6.35%) and a capital value of £1,000 per sq ft. Canary Wharf The Shard The City London Eye South Bank Covent Garden Charing Cross Holborn Trafalgar Square Leicester Square Tottenham Court Road 26 DEAN Leicester Square STREET Soho Square Gardens Tottenham Court Road Western Ticket Hall Oxford Street London West End LOCATION & SITUATION Soho has long cemented its reputation as the excellent. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

16/18 Beak Street Soho, London W1F 9RD Prime Soho Freehold

16/18 Beak Street Soho, London W1F 9RD Prime Soho Freehold INVESTMENT SUMMARY n Attractive, six storey period building occupying a highly prominent corner site. n Situated in a prime Soho position just off Regent Street, in direct proximity of Golden Square and Carnaby Street. n Double fronted restaurant with self contained, high specification, triple aspect offices above. n Total accommodation of 1,097.84 sq m (11,817 sq ft) with regular floorplates of approximately 1,700 sq ft over the upper floors. n Multi let to five tenants with 46% of the income secured against the undoubted covenant of Pizza Express on a new unbroken 15 year lease. n Total rent passing of £645,599 per annum. n Newly let restaurant, and reversionary offices, let off a low average base rent of less than £50 per sq ft. n Substantial freehold interest. n Multiple asset management opportunities to enhance value. n Seeking offers in excess of £12.85 million reflecting the following attractive yield profile and a capital value of £1,087 per sq ft: n Net Initial Yield: 4.75% n Equivalent Yield: 5.15% n Reversionary Yield: 5.30% T W STREE RET IM R RGA E MA P G OLE CAVENDISH E SQUARE N T S S TR T R TOTTENHAM E E E E E COURT ROAD T AC L T A P ST TT . G FORD STREET IL HENRIE OX E S HI GH ST. SOHO SQUARE P O OXFORD B LA E CIRCUS RW N EET R D C I FORD ST CK H OX S A T WA T RE STRE G R EE R I R R N . -

Arts Books & Ephemera

Arts 5. Dom Gusman vole les Confitures chez le Cardinal, dont il est reconnu. Tome 2, 1. Adoration Des Mages. Tableau peint Chap. 6. par Eugene Deveria pour l'Eglise de St. Le Mesle inv. Dupin Sculp. A Paris chez Dupin rue St. Jacques A.P.D.R. [n.d., c.1730.] Leonard de Fougeres. Engraving, 320 x 375mm. 12½ x 14¾". Slightly soiled A. Deveria. Lith. de Lemercier. [n.d., c.1840.] and stained. £160 Lithograph, sheet 285 x 210mm. 11¼ x 8¼". Lightly Illustration of a scene from Dom Juan or The Feast foxed. £80 with the Statue (Dom Juan ou le Festin de pierre), a The Adoration of the Magi is the name traditionally play by Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, known by his stage given to the representation in Christian art of the three name Molière (1622 - 1673). It is based on the kings laying gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh legendary fictional libertine Don Juan. before the infant Jesus, and worshiping Him. This Engraved and published in Paris by Pierre Dupin interpretation by Eugene Deveria (French, 1808 - (c.1690 - c.1751). 1865). From the Capper Album. Plate to 'Revue des Peintres' by his brother Achille Stock: 10988 Devéria (1800 - 1857). As well as a painter and lithographer, Deveria was a stained-glass designer. Numbered 'Pl 1.' upper right. Books & Ephemera Stock: 11084 6. Publicola's Postscript to the People of 2. Vauxhall Garden. England. ... If you suppose that Rowlandson & Pugin delt. et sculpt. J. Bluck, aquat. Buonaparte will not attempt Invasion, you London Pub. Octr. 1st. 1809, at R. -

8-12 Broadwick Street

8-12 BROADWICK STREET 898 sq ft of contemporary loft-style office space on the 4th floor UNIQUE space 8-12 Broadwick Street is a unique office building in the heart of Soho. The available loft-style space is on the 4th floor and has been refurbished in a contemporary style. The office features a large central skylight, views over Soho and original timber flooring. The floor benefits from a demised WC and shower as well as a fitted kitchenette. SPECIFICATION • Loft-style offices with fantastic natural light • Original parquet timber flooring • Demised WC and shower • Perimeter trunking • New comfort cooling system • Refurbished entrance and common parts • Fitted kitchenette • Lift to 3rd floor • BT internet available 4th FLOOR PLAN 898 sq ft / 84 sq m Shower NORTH Kitchen CLICK HERE FOR VIRTUAL tour 360 BROADWICK STREET LOCATION Broadwick Street sits in an area of Soho famed for its record shops, markets and restaurant scene, with the iconic Carnaby Street an easy walking distance away. There are excellent transport links available, with Tottenham Court Road, Oxford Circus, Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus within a 10-minute walk. Oxford Street Oxford Berwick Street Tottenham Court Road Circus BREWDOG Dean Street SOULCYCLE Noel Street Street Wardour Poland Street Poland Tenants will benefit from discounts from tens of Soho food, drink and fashion staples with the Soho NEIGHBOURHOOD London Soho Square TED’S Gin Club CARD. Neighbourhood Card holders are BLANCHETTE GROOMING CARNABY entitled to receive 10% off full price STREET D’Arblay Street merchandise, menus or services at Sheraton Street participating stores, restaurants, bars and cafés across Soho and Carnaby. -

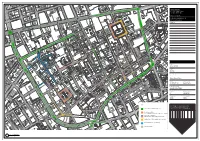

Soho OS Map SKETCH-BEN

RATHBONE BERNERS PLACE STREET REGENT STREET MARGARET STREET OXFORD GREAT NEW STREET BERNERS TITCHFIELD PLACE STREET WELLS EASTCASTLE STREET STREET STREET BUCKNALL Margaret Perry's ST GILES' CIRCUS GREAT Court Transit Studio Place PORTLAND STREET 43 Frith Street, Soho, OXFORD Adam ROAD STREET MARKET and STREET ROMAN PLACE EARNSHAW Eve BUCKNALL London, W1D 4SA Court STREET WINSLEY FALCONBERG MARKET 020 3877 0006 STREET SOHO PLACE MEWS Central STREET STREET CASTLE St Giles [email protected] GREAT Piazza transitstudio.co.uk PLACE Post MARKET ST GILES STREET HIGH HIGH GILES STREET GREAT STREET ST Market Revisions CASTLE GREAT PLACE Hospital Wall Court CHAPEL ROW DENMARK STREET SUTTON OXFORD SQUARE STREET SOHO ROAD ROMAN WARDOUR STREET HOLLEN STREET STREET DENMARK 5 STREET St Giles YARD Hospital GOSLETT (site of) COMPTON NEW OXFORD CIRCUS HILLS PLACE STREET ORANGE NOEL STREET Argyll Swallow Passage PLACE SQUARE RAMILLIES CARLISLE Post YARD Street STREET SOHO RAMILLIES Play Area SHERATON STREET St BERWICK DEAN STREET Flitcroft MANETTE STREET STREET SWALLOW Bateman's Ps REGENT ST CHARING GILES PLACE Buildings PASSAGE STREET CROSS STACEY STREET D'ARBLAY WARDOUR STREET Posts ROAD POLAND STREET MEWS STREET STREET CHAPONE STREET SM ARGYLL PLACE COMPTON PHOENIX ARGYLL LITTLE NEW Court Anne's STREET St Posts GREEK STREET STREET PORTLAND MEWS ROYALTY MARLBOROUGH BUILDINGS MEWS GREAT RICHMOND FRITH Car Park WARDOUR STREET St Giles House STREET STREET Ct STREET Flaxman BATEMAN Walk St LIVONIA Caxton STREET AVENUE Greek Marlborough Posts BROADWICK -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

Everything Goes in Soho

13 BATEMAN ST Put yourself at the centre. Four apartments of this exquisite quality and style Soho’s legendary social prowess is the key inspiration just don’t exist in Soho. They are rare; a prize for for the look and feel of the spaces. Layouts echo the the buyer that understands the importance of this area’s venerated bars, encouraging easy flow between location. They are immaculate; a showcase for different areas. Lighting is intelligently designed to modern design and spatial art. They are characterful; blend from day to night and to capture your mood, residences inspired by their eclectic address. And whatever it is. Integrated speakers take the music into they are state-of-the-art; their technology exists to every room. Materials and finishes chime with those seamlessly move with their residents. of the finest Soho establishments. Dean Street Townhouse 04 • 13 BATEMAN ST TOTTENHAM CT. RD. SO O 5 MINUTE WALK (Crossrail opening 2017) K L A W E T U N I M Your Soho Neighbourhood. 8 XFORD STREET Bateman Street is true Soho. O 11 It links Dean Street and Greek Street, crossing Frith street OXFORD CIRCUS 10 at its mid-point. It is fundamental to the grid that holds 09 Soho Square Gardens, Ronnie Scotts, Soho Theatre and 01 too many bars, restaurants, shops and services to name. CHARING CROSS RO DEAN ST H STREET 05 R E 10 ET GR T MARLBOROUG 02 GREA EEK STREET15 14 07 WAR DINING And DRINKING POINTS OF INTEREST 13 07 DOUR STREET 01 01 Dean Street Town House Soho Square 19 AD TEMAN STREET POL BERWICK STREET BA 02 02 12 C Barrafina Golden Square ARNABY STREET 04 AND STREET 03 Bocca Di Lupo 03 St Annes Churchyard 01 18 02 08 06 20 03 04 Social Eating House Gardens 16 01 FRIT 05 H 02 Bob Bob Richard STREET 14 06 Yauatcha 01 09 17 SHOPPING 03 07 Refuel Bar & Restaurant Soho Hotel 12 04 07 Carnaby Street ON STREET 08 China Town REGENT STREET 08 13 05 01 Cheap Monday 04 09 Bao LEX OLD COMPT INGT 02 Diesel 05 10 06 Bo drake ON STREET BEAK STREET 03 Scotch and Soda 03 11 Ham Yard 04 Vans 12 Bone Daddies 03 05 Dr.