Hox11 Paralogous Genes Are Essential for Metanephric Kidney Induction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Neuronal Differentiation and Cell-Cycle Programs Mediate Response to BET-Bromodomain Inhibition in MYC-Driven Medulloblastoma

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10307-9 OPEN Neuronal differentiation and cell-cycle programs mediate response to BET-bromodomain inhibition in MYC-driven medulloblastoma Pratiti Bandopadhayay et al.# BET-bromodomain inhibition (BETi) has shown pre-clinical promise for MYC-amplified medulloblastoma. However, the mechanisms for its action, and ultimately for resistance, have 1234567890():,; not been fully defined. Here, using a combination of expression profiling, genome-scale CRISPR/Cas9-mediated loss of function and ORF/cDNA driven rescue screens, and cell- based models of spontaneous resistance, we identify bHLH/homeobox transcription factors and cell-cycle regulators as key genes mediating BETi’s response and resistance. Cells that acquire drug tolerance exhibit a more neuronally differentiated cell-state and expression of lineage-specific bHLH/homeobox transcription factors. However, they do not terminally differentiate, maintain expression of CCND2, and continue to cycle through S-phase. Moreover, CDK4/CDK6 inhibition delays acquisition of resistance. Therefore, our data provide insights about the mechanisms underlying BETi effects and the appearance of resistance and support the therapeutic use of combined cell-cycle inhibitors with BETi in MYC-amplified medulloblastoma. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to C.M.J. (email: [email protected]) or to R.B. (email: [email protected]). #A full list of authors and their affiliations appears at the end of the paper. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | (2019) 10:2400 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10307-9 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications 1 ARTICLE NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10307-9 YC-driven group 3 medulloblastoma is an aggressive Genes suppressed by BETi tend to be cell-essential. -

Mapping Chromatin Accessibility and Active Regulatory Elements Reveals New Pathological Mechanisms in Human Gliomas

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/867861; this version posted March 20, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Mapping chromatin accessibility and active regulatory elements reveals new pathological mechanisms in human gliomas Authors/Affiliations Karolina Stępniak1*, Magdalena A. Machnicka2*, Jakub Mieczkowski1*, Anna Macioszek2, Bartosz Wojtaś1, Bartłomiej Gielniewski1, Sylwia K. Król1, Rafał Guzik1, Michał J. Dąbrowski3, Michał Dramiński3, Marta Jardanowska3, Ilona Grabowicz3, Agata Dziedzic3, Hanna Kranas2a, Karolina Sienkiewicz2, Klev Diamanti4, Katarzyna Kotulska5, Wiesława Grajkowska5, Marcin Roszkowski5, Tomasz Czernicki6, Andrzej Marchel6, Jan Komorowski4, Bozena Kaminska1#, Bartek Wilczyński2# 1 Nencki Institute of Experimental Biology of the Polish Academy of Sciences; Warsaw, 02-093, Poland 2 Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Mechanics, University of Warsaw, Warsaw, 02-097, Poland 3 Institute of Computer Science of the Polish Academy of Sciences; Warsaw, 01-248 Poland 4 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, 75124, Sweden 5 Deptartments of Neurology, Neurosurgery, Neuropathology, The Children's Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, 02-093, Poland 6 Department of Neurosurgery, Medical University of Warsaw, Warsaw, 02-097, Poland. *Equally contributing authors # Corresponding authors Contact Info: [email protected]; [email protected] Summary Chromatin structure and accessibility, and combinatorial binding of transcription factors to regulatory elements in genomic DNA control transcription. Genetic variations in genes encoding histones, epigenetics-related enzymes or modifiers affect chromatin structure/dynamics and result in alterations in gene expression contributing to cancer development or progression. -

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Bone Morphogenetic Protein 4 Promotes

www.intjdevbiol.com doi: 10.1387/ijdb.160040mk SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL corresponding to: Bone morphogenetic protein 4 promotes craniofacial neural crest induction from human pluripotent stem cells SUMIYO MIMURA, MIKA SUGA, KAORI OKADA, MASAKI KINEHARA, HIROKI NIKAWA and MIHO K. FURUE* *Address correspondence to: Miho Kusuda Furue. Laboratory of Stem Cell Cultures, National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition, 7-6-8, Saito-Asagi, Ibaraki, Osaka 567-0085, Japan. Tel: 81-72-641-9819. Fax: 81-72-641-9812. E-mail: [email protected] Full text for this paper is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1387/ijdb.160040mk TABLE S1 PRIMER LIST FOR QRT-PCR Gene forward reverse AP2α AATTTCTCAACCGACAACATT ATCTGTTTTGTAGCCAGGAGC CDX2 CTGGAGCTGGAGAAGGAGTTTC ATTTTAACCTGCCTCTCAGAGAGC DLX1 AGTTTGCAGTTGCAGGCTTT CCCTGCTTCATCAGCTTCTT FOXD3 CAGCGGTTCGGCGGGAGG TGAGTGAGAGGTTGTGGCGGATG GAPDH CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC CCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG MSX1 GGATCAGACTTCGGAGAGTGAACT GCCTTCCCTTTAACCCTCACA NANOG TGAACCTCAGCTACAAACAG TGGTGGTAGGAAGAGTAAAG OCT4 GACAGGGGGAGGGGAGGAGCTAGG CTTCCCTCCAACCAGTTGCCCCAAA PAX3 TTGCAATGGCCTCTCAC AGGGGAGAGCGCGTAATC PAX6 GTCCATCTTTGCTTGGGAAA TAGCCAGGTTGCGAAGAACT p75 TCATCCCTGTCTATTGCTCCA TGTTCTGCTTGCAGCTGTTC SOX9 AATGGAGCAGCGAAATCAAC CAGAGAGATTTAGCACACTGATC SOX10 GACCAGTACCCGCACCTG CGCTTGTCACTTTCGTTCAG Suppl. Fig. S1. Comparison of the gene expression profiles of the ES cells and the cells induced by NC and NC-B condition. Scatter plots compares the normalized expression of every gene on the array (refer to Table S3). The central line -

1714 Gene Comprehensive Cancer Panel Enriched for Clinically Actionable Genes with Additional Biologically Relevant Genes 400-500X Average Coverage on Tumor

xO GENE PANEL 1714 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes 400-500x average coverage on tumor Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11 IL6R KAT5 ACVR2A -

HER2 Gene Signatures: (I) Novel and (Ii) Established by Desmedt Et Al 2008 (31)

Table S1: HER2 gene signatures: (i) Novel and (ii) Established by Desmedt et al 2008 (31). Pearson R [neratinib] is the correlation with neratinib response using a pharmacogenomic model of breast cancer cell lines (accessed online via CellMinerCDB). *indicates significantly correlated genes. n/a = data not available in CellMinerCDB Genesig N Gene ID Pearson R [neratinib] p-value (i) Novel 20 ERBB2 0.77 1.90E-08* SPDEF 0.45 4.20E-03* TFAP2B 0.2 0.24 CD24 0.38 0.019* SERHL2 0.41 0.0097* CNTNAP2 0.12 0.47 RPL19 0.29 0.073 CAPN13 0.51 1.00E-03* RPL23 0.22 0.18 LRRC26 n/a n/a PRODH 0.42 9.00E-03* GPRC5C 0.44 0.0056* GGCT 0.38 1.90E-02* CLCA2 0.31 5.70E-02 KDM5B 0.33 4.20E-02* SPP1 -0.25 1.30E-01 PHLDA1 -0.54 5.30E-04* C15orf48 0.06 7.10E-01 SUSD3 -0.09 5.90E-01 SERPINA1 0.14 4.10E-01 (ii) Established 24 ERBB2 0.77 1.90E-08* PERLD1 0.77 1.20E-08* PSMD3 0.33 0.04* PNMT 0.33 4.20E-02* GSDML 0.4 1.40E-02* CASC3 0.26 0.11 LASP1 0.32 0.049* WIPF2 0.27 9.70E-02 EPN3 0.42 8.50E-03* PHB 0.38 0.019* CLCA2 0.31 5.70E-02 ORMDL2 0.06 0.74 RAP1GAP 0.53 0.00059* CUEDC1 0.09 0.61 HOXC11 0.2 0.23 CYP2J2 0.45 0.0044* HGD 0.14 0.39 ABCA12 0.07 0.67 ATP2C2 0.42 0.0096* ITGA3 0 0.98 CEACAM5 0.4 0.012* TMEM16K 0.15 0.37 NR1D1 n/a n/a SNX7 -0.28 0.092 FJX1 -0.26 0.12 KCTD9 -0.11 0.53 PCTK3 -0.04 0.83 CREG1 0.17 0.3 Table S2: Up-regulated genes from the top 500 DEGs for each comparison by WAD score METABRIC METABRIC METABRIC TCGA ERBB2amp ERBB2mut oncERBB2mut HER2+ ERBB2 PIP ANKRD30A ERBB2 GRB7 CYP4Z1 CYP4Z1 SCGB2A2 PGAP3 PROM1 LRRC26 SPDEF GSDMB CD24 PPP1R1B FOXA1 -

Whole-Exome Sequencing of Metastatic Cancer and Biomarkers of Treatment Response

Supplementary Online Content Beltran H, Eng K, Mosquera JM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of metastatic cancer and biomarkers of treatment response. JAMA Oncol. Published online May 28, 2015. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1313 eMethods eFigure 1. A schematic of the IPM Computational Pipeline eFigure 2. Tumor purity analysis eFigure 3. Tumor purity estimates from Pathology team versus computationally (CLONET) estimated tumor purities values for frozen tumor specimens (Spearman correlation 0.2765327, p- value = 0.03561) eFigure 4. Sequencing metrics Fresh/frozen vs. FFPE tissue eFigure 5. Somatic copy number alteration profiles by tumor type at cytogenetic map location resolution; for each cytogenetic map location the mean genes aberration frequency is reported eFigure 6. The 20 most frequently aberrant genes with respect to copy number gains/losses detected per tumor type eFigure 7. Top 50 genes with focal and large scale copy number gains (A) and losses (B) across the cohort eFigure 8. Summary of total number of copy number alterations across PM tumors eFigure 9. An example of tumor evolution looking at serial biopsies from PM222, a patient with metastatic bladder carcinoma eFigure 10. PM12 somatic mutations by coverage and allele frequency (A) and (B) mutation correlation between primary (y- axis) and brain metastasis (x-axis) eFigure 11. Point mutations across 5 metastatic sites of a 55 year old patient with metastatic prostate cancer at time of rapid autopsy eFigure 12. CT scans from patient PM137, a patient with recurrent platinum refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma eFigure 13. Tracking tumor genomics between primary and metastatic samples from patient PM12 eFigure 14. -

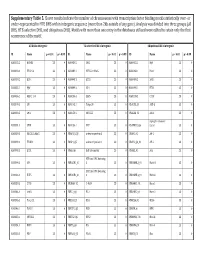

Supplementary Table 5. Clover Results Indicate the Number Of

Supplementary Table 5. Clover results indicate the number of chromosomes with transcription factor binding motifs statistically over‐ or under‐represented in HTE DHS within intergenic sequence (more than 2kb outside of any gene). Analysis was divided into three groups (all DHS, HTE‐selective DHS, and ubiquitous DHS). Motifs with more than one entry in the databases utilized were edited to retain only the first occurrence of the motif. All DHS x Intergenic TEselective DHS x Intergenic Ubiquitous DHS x Intergenic ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 ID Name p < 0.01 p > 0.99 MA0002.2 RUNX1 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0055.1 Myf 23 0 MA0003.1 TFAP2A 23 0 MA0089.1 NFE2L1::MafG 23 0 MA0068.1 Pax4 23 0 MA0039.2 Klf4 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0055.1 Myf 23 0 MA0099.2 AP1 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 MA0056.1 MZF1_1‐4 23 0 MA0136.1 ELF5 23 0 MA0139.1 CTCF 23 0 MA0079.2 SP1 23 0 MA0145.1 Tcfcp2l1 23 0 V$ALX3_01 ALX‐3 23 0 MA0080.2 SPI1 23 0 MA0150.1 NFE2L2 23 0 V$ALX4_02 Alx‐4 23 0 myocyte enhancer MA0081.1 SPIB 23 0 MA0156.1 FEV 23 0 V$AMEF2_Q6 factor 23 0 MA0089.1 NFE2L1::MafG 23 0 V$AP1FJ_Q2 activator protein 1 23 0 V$AP1_01 AP‐1 23 0 MA0090.1 TEAD1 23 0 V$AP4_Q5 activator protein 4 23 0 V$AP2_Q6_01 AP‐2 23 0 MA0098.1 ETS1 23 0 V$AR_Q6 half‐site matrix 23 0 V$ARX_01 Arx 23 0 BTB and CNC homolog MA0099.2 AP1 23 0 V$BACH1_01 1 23 0 V$BARHL1_01 Barhl‐1 23 0 BTB and CNC homolog MA0136.1 ELF5 23 0 V$BACH2_01 2 23 0 V$BARHL2_01 Barhl2 23 0 MA0139.1 CTCF 23 0 V$CMAF_02 C‐MAF 23 0 V$BARX1_01 Barx1 23 0 MA0144.1 Stat3 23 0 -

![HOXC11 Mouse Monoclonal Antibody [Clone ID: OTI2A10] Product Data](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6024/hoxc11-mouse-monoclonal-antibody-clone-id-oti2a10-product-data-1576024.webp)

HOXC11 Mouse Monoclonal Antibody [Clone ID: OTI2A10] Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for CF502574 HOXC11 Mouse Monoclonal Antibody [Clone ID: OTI2A10] Product data: Product Type: Primary Antibodies Clone Name: OTI2A10 Applications: FC, IF, IHC, WB Recommended Dilution: WB 1:500, IHC 1:150, IF 1:100, FLOW 1:100 Reactivity: Human, Mouse, Rat Host: Mouse Isotype: IgG2b Clonality: Monoclonal Immunogen: Full length human recombinant protein of human HOXC11(NP_055027) produced in E.coli. Formulation: Lyophilized powder (original buffer 1X PBS, pH 7.3, 8% trehalose) Reconstitution Method: For reconstitution, we recommend adding 100uL distilled water to a final antibody concentration of about 1 mg/mL. To use this carrier-free antibody for conjugation experiment, we strongly recommend performing another round of desalting process. (OriGene recommends Zeba Spin Desalting Columns, 7KMWCO from Thermo Scientific) Purification: Purified from mouse ascites fluids or tissue culture supernatant by affinity chromatography (protein A/G) Conjugation: Unconjugated Storage: Store at -20°C as received. Stability: Stable for 12 months from date of receipt. Predicted Protein Size: 33.6 kDa Gene Name: Homo sapiens homeobox C11 (HOXC11), mRNA. Database Link: NP_055027 Entrez Gene 3227 Human O43248 This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 3 HOXC11 Mouse Monoclonal Antibody [Clone ID: OTI2A10] – CF502574 Background: This gene belongs to the homeobox family of genes. -

Implications for Acquired Resistance to Endocrine Therapy Rachel Bleach1, Stephen F

Published OnlineFirst May 20, 2021; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4135 CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH | PRECISION MEDICINE AND IMAGING Steroid Ligands, the Forgotten Triggers of Nuclear Receptor Action; Implications for Acquired Resistance to Endocrine Therapy Rachel Bleach1, Stephen F. Madden2, James Hawley3, Sara Charmsaz1, Cigdem Selli4, Katherine M. Sheehan5, Leonie S. Young1, Andrew H. Sims4, Pavel Soucek6,7, Arnold D. Hill1,8, and Marie McIlroy1 ABSTRACT ◥ Purpose: There is strong epidemiologic evidence indicating that Results: AR protein expression was associated with favorable estrogens may not be the sole steroid drivers of breast cancer. We progression-free survival in the total population (Wilcoxon, P < hypothesize that abundant adrenal androgenic steroid precursors, 0.001). Pretherapy serum samples from breast cancer patients acting via the androgen receptor (AR), promote an endocrine- showed decreasing levels of 4AD with age only in the nonre- resistant breast cancer phenotype. current group (P < 0.05). LC/MS-MS analysis of an AI-sensitive Experimental Design: AR was evaluated in a primary breast and AI-resistant cohort demonstrated the ability to detect altered cancer tissue microarray (n ¼ 844). Androstenedione (4AD) levels of steroids in serum of patients before and after AI therapy. levels were evaluated in serum samples (n ¼ 42) from hormone Transcriptional analysis showed an increased ratio of AR:ER receptor–positive, postmenopausal breast cancer. Levels of signaling pathway activities in patients failing AI therapy (t test P androgens, progesterone, and estradiol were quantified using < 0.05); furthermore, 4AD mediated gene changes associated LC/MS-MS in serum from age- and grade-matched recurrent with acquired AI resistance. -

1 Novel Expression Signatures Identified by Transcriptional Analysis

ARD Online First, published on October 7, 2009 as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 on 7 October 2009. Downloaded from Novel expression signatures identified by transcriptional analysis of separated leukocyte subsets in SLE and vasculitis 1Paul A Lyons, 1Eoin F McKinney, 1Tim F Rayner, 1Alexander Hatton, 1Hayley B Woffendin, 1Maria Koukoulaki, 2Thomas C Freeman, 1David RW Jayne, 1Afzal N Chaudhry, and 1Kenneth GC Smith. 1Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and Department of Medicine, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK 2Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Roslin, Midlothian, EH25 9PS, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Paul Lyons or Prof Kenneth Smith, Department of Medicine, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK. Telephone: +44 1223 762642, Fax: +44 1223 762640, E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Key words: Gene expression, autoimmune disease, SLE, vasculitis Word count: 2,906 The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in their licence (http://ard.bmj.com/ifora/licence.pdf). http://ard.bmj.com/ on September 29, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. 1 Copyright Article author (or their employer) 2009. -

Xo PANEL DNA GENE LIST

xO PANEL DNA GENE LIST ~1700 gene comprehensive cancer panel enriched for clinically actionable genes with additional biologically relevant genes (at 400 -500x average coverage on tumor) Genes A-C Genes D-F Genes G-I Genes J-L AATK ATAD2B BTG1 CDH7 CREM DACH1 EPHA1 FES G6PC3 HGF IL18RAP JADE1 LMO1 ABCA1 ATF1 BTG2 CDK1 CRHR1 DACH2 EPHA2 FEV G6PD HIF1A IL1R1 JAK1 LMO2 ABCB1 ATM BTG3 CDK10 CRK DAXX EPHA3 FGF1 GAB1 HIF1AN IL1R2 JAK2 LMO7 ABCB11 ATR BTK CDK11A CRKL DBH EPHA4 FGF10 GAB2 HIST1H1E IL1RAP JAK3 LMTK2 ABCB4 ATRX BTRC CDK11B CRLF2 DCC EPHA5 FGF11 GABPA HIST1H3B IL20RA JARID2 LMTK3 ABCC1 AURKA BUB1 CDK12 CRTC1 DCUN1D1 EPHA6 FGF12 GALNT12 HIST1H4E IL20RB JAZF1 LPHN2 ABCC2 AURKB BUB1B CDK13 CRTC2 DCUN1D2 EPHA7 FGF13 GATA1 HLA-A IL21R JMJD1C LPHN3 ABCG1 AURKC BUB3 CDK14 CRTC3 DDB2 EPHA8 FGF14 GATA2 HLA-B IL22RA1 JMJD4 LPP ABCG2 AXIN1 C11orf30 CDK15 CSF1 DDIT3 EPHB1 FGF16 GATA3 HLF IL22RA2 JMJD6 LRP1B ABI1 AXIN2 CACNA1C CDK16 CSF1R DDR1 EPHB2 FGF17 GATA5 HLTF IL23R JMJD7 LRP5 ABL1 AXL CACNA1S CDK17 CSF2RA DDR2 EPHB3 FGF18 GATA6 HMGA1 IL2RA JMJD8 LRP6 ABL2 B2M CACNB2 CDK18 CSF2RB DDX3X EPHB4 FGF19 GDNF HMGA2 IL2RB JUN LRRK2 ACE BABAM1 CADM2 CDK19 CSF3R DDX5 EPHB6 FGF2 GFI1 HMGCR IL2RG JUNB LSM1 ACSL6 BACH1 CALR CDK2 CSK DDX6 EPOR FGF20 GFI1B HNF1A IL3 JUND LTK ACTA2 BACH2 CAMTA1 CDK20 CSNK1D DEK ERBB2 FGF21 GFRA4 HNF1B IL3RA JUP LYL1 ACTC1 BAG4 CAPRIN2 CDK3 CSNK1E DHFR ERBB3 FGF22 GGCX HNRNPA3 IL4R KAT2A LYN ACVR1 BAI3 CARD10 CDK4 CTCF DHH ERBB4 FGF23 GHR HOXA10 IL5RA KAT2B LZTR1 ACVR1B BAP1 CARD11 CDK5 CTCFL DIAPH1 ERCC1 FGF3 GID4 HOXA11