Autumn Migration Speed of Juvenile Reed and Sedge Warblers in Relation to Date and Fat Loads’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Common Cuckoo Is an Effective Indicator of High Bird Species

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The common cuckoo is an effective indicator of high bird species richness in Asia and Europe Received: 16 February 2017 Federico Morelli1, Anders Pape Møller2, Emma Nelson3, Yanina Benedetti1, Wei Liang 4, Accepted: 19 May 2017 Petra Šímová 1, Marco Moretti5 & Piotr Tryjanowski6 Published: xx xx xxxx Common cuckoo Cuculus canorus is a charismatic bird species with a dominant presence in human culture: from folklore legends to nowadays there is evidence of cuckoos being a prime candidate as a surrogate of bird diversity. Recent studies demonstrated that the cuckoo can predict hotspots of taxonomic diversity and functional diversity of bird communities in European countries. In this study, we demonstrated that the cuckoo is an excellent bioindicator at multi-spatial scale, extending cuckoo surrogacy from Europe to Asia. Even using three different survey methods (transect, square, point counts), comparing the new findings with results of our research in Europe, sites where the cuckoo is present were characterized by greater species richness, while the cuckoo was absent from sites with low species richness. The goodness of fit of models based on point counts ranged between 71 and 92%. Furthermore, the cuckoo population trend mirrors the average population trend and climate suitability of overall bird communities in Europe. The common cuckoo is therefore a suitable intercontinental bioindicator of hotspots of bird richness, even under climate change scenarios or in areas where the species co-occurs with other cuckoo species, opening a new avenue for standardized citizen science on bird biodiversity surveys worldwide. Why is the common cuckoo Cuculus canorus a fascinating bird species for humans? What are the main reasons for the species being known as “a messenger of spring and morality”1, and why is it so conspicuous in human culture? A review of folklore shows clearly that the enigmatic cuckoo has driven the collective imagination of people throughout the world for thousands of years. -

Migratory State: Body Mass and Fat Level of Some Passerine Long-Distance Migrants During Autumn Migration in North-Eastern Bulgaria

MIGRATORY STATE: BODY MASS AND FAT LEVEL OF SOME PASSERINE LONG-DISTANCE MIGRANTS DURING AUTUMN MIGRATION IN NORTH-EASTERN BULGARIA Mihaela Ilieva and Pavel Zehtindjiev ABSTRACT Ilieva M., Zehtindjiev P. 2005. Migratory state: body mass and fat level of some passerine long- distance migrants during autumn migration in north-eastern Bulgaria. Ring 27, 1: 61-67. Body condition of 3224 migrating birds of Great Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus arundinaceus), Sedge Warbler (A. schoenobaenus), Willow Warbler (Phylloscopus trochilus), Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) and Whitethroat (Sylvia communis) was studied at Kalimok Station, NE Bulgaria (41°00N 26°26E) in the autumns of 1997-2003. The mean values of the fat level and the body mass were calculated for each species and year and were compared with similar data of various parts of the Palaearctic-African Migration System. Distinct variations in the mean values of studied parameters in different years were recorded. The dynamics of the ac- cumulated subcutaneous fat and the body mass during the autumn varied in different species and either increase or decrease of the values during a certain season were registered. Age- determined differences in the studied characteristics were found. The timing of the passage of the first-year and adult birds can influence the dynamics of the mean fat level and the mean body mass. The lack of selective environment in NE Balkan Peninsula allows the pas- sage of conspecific birds in various migratory states. The realisation of their migration adap- tations highly depends on environmental conditions during the period of passage. M. Ilieva and P. Zehtindjiev, Insitute of Zoology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Blvd. -

Thick-Billed Warbler (Iduna Aedon) at Gambell, Alaska: First Record for North America Gary H

NOTES THICK-BILLED WARBLER (IDUNA AEDON) AT GAMBELL, ALASKA: FIRST RECORD FOR NORTH AMERICA GARY H. ROSENBERG, 8101 North Wheatfield Dr., Tucson, Arizona 85741; [email protected] PAUL E. LEHMAN, 11192 Portobelo Dr., San Diego, California 92124; [email protected] AARON J. LANG, 40208 Alpenglow Circle, Homer, Alaska 99603; [email protected] VICTOR AND RUBEN STOLL, 899 Miller Rd., Centerville, Tennessee 37033; [email protected] In the evening on 8 September 2017, in the “far boneyard” at Gambell, St. Law- rence Island, Alaska (63.78° N, 171.74° W), Victor and Ruben Stoll flushed a pas- serine they could not immediately identify. The “boneyards” are large pits excavated by the resident Yupik Natives seeking buried ivory and artifacts, a result of several thousand years of sea-mammal hunting from this island’s Northwest Cape. Working these pits turns the soil, which has resulted in the growth of relatively lush vegetation consisting of two species of Artemisia, known locally as “wormwood.” The combina- tion of lush vegetation (reaching 0.5–1 m in height) and deep depressions that offer protection from the wind is attractive to migrant and vagrant landbirds in the otherwise flat, gravelly landscape. Soon thereafter, we, along with Greg Scyphers, Monte Taylor, and other birders then at Gambell, converged at the far boneyard in search of the bird. It was soon relocated and seen on the ground briefly by Lang, who suggested it was a Thick-billed Warbler (Iduna aedon), a bird he was familiar with from southeastern Asia and a species not previously recorded in Alaska or North America. -

First Photographs of Aquatic Warbler Acrocephalus Paludicola in the Field from Africa and a Request for Observations Volker Salewski

Photospot: First photographs of Aquatic Warbler Acrocephalus paludicola in the field from Africa and a request for observations Volker Salewski Premières photos du Phragmite aquatique Acrocephalus paludicola sur le terrain en Afrique. Le Phragmite aquatique Acrocephalus paludicola est le seul passériforme mondialement menacé nichant en Europe continentale. La localisation des sites de stationnement et quartiers d’hivernage en Afrique s’avère essentielle à la conservation de l’espèce mais est gênée par le manque de connaissances de cette espèce rare de la part des observateurs. L’auteur présente probablement les premières photos de l’espèce dans son habitat naturel en Afrique de l’Ouest et décrit les critères d’identification principaux, surtout par rapport au Phragmite des joncs A. schoenobaenus. Finalement, un appel est lancé aux observateurs pour envoyer toutes leurs données à l’Équipe de Conservation du Phragmite aquatique de BirdLife International. quatic Warbler Acrocephalus paludicola is the wintering site was found in Mali (Poluda et al. A only globally threatened passerine species in press). In order to implement a conservation that breeds in continental Europe. Formerly more strategy for Aquatic Warblers during the non- widespread, its population decreased dramatically breeding season, the species’ precise wintering during the 20th century (Flade & Lachmann areas in Africa must be identified. However, 2008). The species is a migrant, spending the non- finding the species requires knowledge of its breeding season in sub-Saharan Africa, but until preferred habitats and identification may present a recently no wintering areas were known. In 2007 challenge to observers unfamiliar with the species. an important non-breeding site was discovered To my knowledge, there are no photographs around Djoudj National Park in northern Senegal of Aquatic Warblers in their natural habitat (Salewski et al. -

Individual Female Common Cuckoos Cuculus Canorus Lay Constant Egg Types but Egg Appearance Cannot Be Used to Assign Eggs to Females

J. Avian Biol. 39: 238Á241, 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.2008.0908-8857.04158.x # 2008 The Authors. J. Compilation # 2008 J. Avian Biol. Received 28 December 2006, accepted 5 June 2007 Individual female common cuckoos Cuculus canorus lay constant egg types but egg appearance cannot be used to assign eggs to females Arne Moksnes, Eivin Røskaft, Geir Rudolfsen, Sigrun Skjelseth, Ba˚rd G. Stokke, Oddmund Kleven, H. Lisle Gibbs, Marcel Honza, Barbara Taborsky, Yvonne Teuschl, Wolfgang Vogl and Michael Taborsky A. Moksnes (correspondence), E. Røskaft, S. Skjelseth, and B. G. Stokke, Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Realfagbygget, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway. E-mail: [email protected]. Á G. Rudolfsen, Department of Zoology/ Ecology, University of Tromsø, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway. Á O. Kleven, Natural History Museum, Department of Zoology, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1172 Blindern, N-0318 Oslo, Norway. Á H. Lisle Gibbs, Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, 1735 Neil Avenue, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA. Á M. Honza, Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 60 365 Brno, Czech Republic. Á B. Taborsky and M. Taborsky, Institute of Zoology, Department of Behavioural Ecology, University of Bern, CH-3032 Hinterkappelen, Switzerland. Á Y. Teuschl, Zoologisches Museum, Universita¨tZu¨rich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zu¨rich, Switzerland. Á W. Vogl, Konrad Lorenz-Institut fu¨r Vergleichende Verhaltensforschung, A-1160 Vienna, Austria. Females of the obligate brood parasitic common cuckoo Cuculus canorus are assumed to lay eggs of consistent colour and pattern and egg characteristics have been used to separate between different individuals. -

Foot-Slapping by Coots During 1978, at Reservoirs and Flooded Gravel-Pits

Notes Foot-slapping by Coots During 1978, at reservoirs and flooded gravel-pits in Northamptonshire, I began to notice single Coots Fulica atra standing on mats of flooded vegetation at the water's edge and slapping the s'urface with one foot. The Coot would stand hunched and slap regularly and deliberately about five or six times, the noise carrying across land for at least 100m. Although I first noticed this behaviour at the beginning of the breeding season, I have observed it throughout the year. It became obvious that, as it was always triggered by the approach of a human being, it served as a warning to other Coots of possible danger: it can be likened somewhat to foot-stamping by rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus. I have not yet determined whether one specific individual of a group of Coots continued.... 126 Notes 127 feeding at the water's edge acts as a guard, or whether it is the Coot nearest to a suitable slapping area that reacts; on one occasion, however, a Coot swam towards an approaching human being, hauled itself out of the water, ran to a weed-patch and began slapping. P, W. RICHARDSON 10 Bedford Cottages, Great Brington, Northampton NN74JE Terrestrial foot-slapping on the nest is mentioned in BH'P volume 2, although its significance is not known. Dr K. E. L. Simmons has commented that Mr Richardson's observations appear to add a new dimension to the foot-slapping display by this species, which is also performed by the Moorhen Gallinula chloropm. EDS Grey Plovers associating with inland Golden Plover flocks During a study of Golden Plovers Pluvialis apricaria wintering in Buckinghamshire, we twice observed Grey Plovers P. -

A New Subspecies of Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus Scirpaceus in Egypt

Jens Hering et al. 101 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(2) A new subspecies of Eurasian Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus in Egypt by Jens Hering, Hans Winkler & Frank D. Steinheimer Received 4 December 2015 Summary.—A new subspecies of European Reed Warbler Acrocephalus scirpaceus is described from the Egypt / Libya border region in the northern Sahara. Intensive studies revealed the new form to be clearly diagnosable within the Eurasian / African Reed Warbler superspecies, especially in biometrics, habitat, breeding biology and behaviour. The range of this sedentary form lies entirely below sea level, in the large depressions of the eastern Libyan Desert, in Qattara, Siwa, Sitra and Al Jaghbub. The most important field characters are the short wings and tarsi, which are significantly different from closely related A. s. scirpaceus, A. s. fuscus and A. s. avicenniae, less so from A. baeticatus cinnamomeus, which is more clearly separated by behaviour / nest sites and toe length. Molecular genetic analyses determined that uncorrected distances to A. s. scirpaceus are 1.0–1.3%, to avicenniae 1.1–1.5% and to fuscus 0.3–1.2%. The song is similar to that of other Eurasian Reed Warbler taxa as well as that of African Reed Warbler A. baeticatus, but the succession of individual elements appears slower than in A. s. scirpaceus and therefore shows more resemblance to A. s. avicenniae. Among the new subspecies’ unique traits are that its preferred breeding habitat in the Siwa Oasis complex, besides stands of reed, is date palms and olive trees. A breeding density of 107 territories per 10 ha was recorded in the cultivated area. -

Reedbed Structure and Habitat Preference of Reed Passerines During the Post-Breeding Period

Biologia, Bratislava, 61/2: 225—230, 2006 225 Reedbed structure and habitat preference of reed passerines during the post-breeding period Alfréd Trnka1 &PavolProkop1,2 1Department of Biology, Trnava University, Priemyselná 4,P.O.Box9,SK-91843 Trnava, Slovakia; e-mail: [email protected] 2Institute of Zoology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 9,SK-84506 Bratislava, Slovakia Abstract: Post-breeding habitats of nine passerine species were studied in the permanently flooded reed beds of ponds near the village Pusté Úľany (SW Slovakia) in 2002. Structural features of reed beds and the abundance of all birds studied were sampled at two sites and eight study plots. The reed bed structure and abundance of four passerines differed considerably between the individual study plots. The variations in vegetation structure were also caused by winter reed burning in the SE part of study area. Stems in burnt reed beds were smaller and thinner than unburnt. Abundance of the reed warbler and to a lesser extent sedge warbler was higher in tall reed beds, while the bearded tit preferred thick reed stems. Position of reed beds along the shore – open water gradient was an important factor in terms of abundance at the study plots in the case of the reed bunting. This species showed a strong preference for the reed bed edge with open water. Horizontal distribution of other species seems to be random, however, the birds with the exception of Savi’s warbler preferred the upper stratum of reed bed in vertical distribution. Our field data corroborate with those found in experimental studies concerning with ecomorphological characteristics of birds. -

The Role of Reedbeds in Secondary Habitats During the Migration and Breeding of Reed Warblers

Ornis Hungarica 2020. 28(1): 76–91. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0006 The role of reedbeds in secondary habitats during the migration and breeding of reed warblers László BOZÓ Received: April 21, 2020 – Revised: May 28, 2020 – Accepted: May 29, 2020 Bozó, L. 2020. The role of reedbeds in secondary habitats during the migration and breeding of reed warblers. – Ornis Hungarica 28(2): 76–91. DOI: 10.2478/orhu-2020-0006 Abstract The reedbeds provide essential habitat for many Acrocephalus and Locustella species during both breeding and migration periods. The nesting and the migration of these species have been the subject of detailed research over the past half century in the Carpathian Basin. However, these studies have focused primarily on natural habitats and large reedbeds and thus, little is known about the role of smaller habitat fragments in the migration and nesting of these species. During my work, I studied the spring and autumn migration of five passerines in a landscape dominated by agricultural land in Southeast Hungary. Field observa- tions were carried out to survey the populations of different species between 2010–2019. To study their migra- tion, I used the method of bird ringing between 2016–2019 in an oleaster forest and a drainage canal. I was able to determine the migration periods of the species and in autumn, to calculate the time spent in the research area based on the recaptures. In conclusion, reedbeds in secondary habitats play a similar role in the migration of the most common Acrocephalus and Locustella species as in the natural habitats in different regions of the Carpathi- an Basin. -

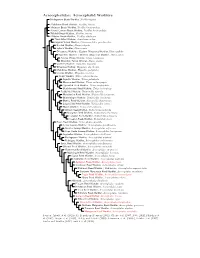

Acrocephalidae Species Tree

Acrocephalidae: Acrocephalid Warblers Madagascan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas typica ?Subdesert Brush-Warbler, Nesillas lantzii ?Anjouan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas longicaudata ?Grand Comoro Brush-Warbler, Nesillas brevicaudata ?Moheli Brush-Warbler, Nesillas mariae ?Aldabra Brush-Warbler, Nesillas aldabrana Thick-billed Warbler, Arundinax aedon Papyrus Yellow Warbler, Calamonastides gracilirostris Booted Warbler, Iduna caligata Sykes’s Warbler, Iduna rama Olivaceous Warbler / Eastern Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna pallida Isabelline Warbler / Western Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna opaca African Yellow Warbler, Iduna natalensis Mountain Yellow Warbler, Iduna similis Upcher’s Warbler, Hippolais languida Olive-tree Warbler, Hippolais olivetorum Melodious Warbler, Hippolais polyglotta Icterine Warbler, Hippolais icterina Sedge Warbler, Titiza schoenobaenus Aquatic Warbler, Titiza paludicola Moustached Warbler, Titiza melanopogon ?Speckled Reed-Warbler, Titiza sorghophila Black-browed Reed-Warbler, Titiza bistrigiceps Paddyfield Warbler, Notiocichla agricola Manchurian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla tangorum Blunt-winged Warbler, Notiocichla concinens Blyth’s Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla dumetorum Large-billed Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla orina Marsh Warbler, Notiocichla palustris African Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla baeticata Mangrove Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla avicenniae Eurasian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla scirpacea Caspian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla fusca Basra Reed-Warbler, Acrocephalus griseldis Lesser Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus gracilirostris Greater Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Settlement, Breeding Success and Song Repertoires of Monogamous and Polygynous Sedge Warblers(Acrocephalus Schoenobaenus)

© Deutschen Ornithologen-Gesellschaft und Partner; download www.do-g.de; www.zobodat.at Die Vogelwarte 39, 1997: 87-94 Settlement, breeding success and song repertoires of monogamous and polygynous Sedge Warblers(Acrocephalus schoenobaenus) ByBen D. Bell, Marta Borowiec, Kim R. McConkey and Ewald Ranoszek Abstract: B ell, B.D., B orow iec , M., M c C onkey , K.R. & E. R a n oszek (1997): Settlement, breeding success and song repertoires of monogamous and polygynous Sedge Warblers(Acrocephalus schoenobaenus). Vogel warte 39: 87-94. Arrival patterns, pairing dates, breeding success and song repertoires of monogamous and polygynous male Sedge Warblers (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus) were compared near Wroclaw, SW Poland. Polygynous males were generally amongst the first to arrive and the first to attain a mate. Both breeding success (no. young fled ged) and song repertoire diversity (no. different syllable types) were greater in polygynous compared with mo nogamous males. The implications of these observations are discussed. Key words: Sedge Warbler(Acrocephalus schoenobaenus), mating system, breeding success, song, Passeres. Addresses: B.D.B., K.R.M., School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington, PO Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand, (current address: K.R.M. Wildlife Research Group, Anatomy Department, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3DY, U.K), M.B., Department of Avian Ecology, Zoological Institute, Univer sity of Wroclaw, Sienkiewicza 21, 50-335 Wroclaw, Poland, E.R., Lesna 7, 56-300 Milicz, Poland. Introduction European warblers of the genusAcrocephalus manifest a variety of mating systems and song cha racteristics (Catchpole 1980, Dyrcz 1988, Dyrcz et al. 1994, Leisler 1985, Leisler & Catchpole 1992).