Radar Observations of the Early Evolution of Bow Echoes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & a Brief Look at the 18

Squall Lines: Meteorology, Skywarn Spotting, & A Brief Look At The 18 June 2010 Derecho Gino Izzi National Weather Service, Chicago IL Outline • Meteorology 301: Squall lines – Brief review of thunderstorm basics – Squall lines – Squall line tornadoes – Mesovorticies • Storm spotting for squall lines • Brief Case Study of 18 June 2010 Event Thunderstorm Ingredients • Moisture – Gulf of Mexico most common source locally Thunderstorm Ingredients • Lifting Mechanism(s) – Fronts – Jet Streams – “other” boundaries – topography Thunderstorm Ingredients • Instability – Measure of potential for air to accelerate upward – CAPE: common variable used to quantify magnitude of instability < 1000: weak 1000-2000: moderate 2000-4000: strong 4000+: extreme Thunderstorms Thunderstorms • Moisture + Instability + Lift = Thunderstorms • What kind of thunderstorms? – Single Cell – Multicell/Squall Line – Supercells Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? – Short/simplistic answer: CAPE vs Shear Thunderstorm Types • What determines T-storm Type? (Longer/more complex answer) – Lot we don’t know, other factors (besides CAPE/shear) include • Strength of forcing • Strength of CAP • Shear WRT to boundary • Other stuff Thunderstorm Types • Multi-cell squall lines most common type of severe thunderstorm type locally • Most common type of severe weather is damaging winds • Hail and brief tornadoes can occur with most the intense squall lines Squall Lines & Spotting Squall Line Terminology • Squall Line : a relatively narrow line of thunderstorms, often -

A 10-Year Radar-Based Climatology of Mesoscale Convective System Archetypes and Derechos in Poland

AUGUST 2020 S U R O W I E C K I A N D T A S Z A R E K 3471 A 10-Year Radar-Based Climatology of Mesoscale Convective System Archetypes and Derechos in Poland ARTUR SUROWIECKI Department of Climatology, University of Warsaw, and Skywarn Poland, Warsaw, Poland MATEUSZ TASZAREK Department of Meteorology and Climatology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznan, Poland, and National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma, and Skywarn Poland, Warsaw, Poland (Manuscript received 29 December 2019, in final form 3 May 2020) ABSTRACT In this study, a 10-yr (2008–17) radar-based mesoscale convective system (MCS) and derecho climatology for Poland is presented. This is one of the first attempts of a European country to investigate morphological and precipitation archetypes of MCSs as prior studies were mostly based on satellite data. Despite its ubiquity and significance for society, economy, agriculture, and water availability, little is known about the climatological aspects of MCSs over central Europe. Our results indicate that MCSs are not rare in Poland as an annual mean of 77 MCSs and 49 days with MCS can be depicted for Poland. Their lifetime ranges typically from 3 to 6 h, with initiation time around the afternoon hours (1200–1400 UTC) and dissipation stage in the evening (1900–2000 UTC). The most frequent morphological type of MCSs is a broken line (58% of cases), then areal/cluster (25%), and then quasi- linear convective systems (QLCS; 17%), which are usually associated with a bow echo (72% of QLCS). QLCS are the feature with the longest life cycle. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Tropical Cyclone Mesoscale Circulation Families

DOMINANT TROPICAL CYCLONE OUTER RAINBANDS RELATED TO TORNADIC AND NON-TORNADIC MESOSCALE CIRCULATION FAMILIES Scott M. Spratt and David W. Sharp National Weather Service Melbourne, Florida 1. INTRODUCTION Doppler (WSR-88D) radar sampling of Tropical Cyclone (TC) outer rainbands over recent years has revealed a multitude of embedded mesoscale circulations (e.g. Zubrick and Belville 1993, Cammarata et al. 1996, Spratt el al. 1997, Cobb and Stuart 1998). While a majority of the observed circulations exhibited small horizontal and vertical characteristics similar to extra- tropical mini supercells (Burgess et al. 1995, Grant and Prentice 1996), some were more typical of those common to the Great Plains region (Sharp et al. 1997). During the past year, McCaul and Weisman (1998) successfully simulated the observed spectrum of TC circulations through variance of buoyancy and shear parameters. This poster will serve to document mesoscale circulation families associated with six TC's which made landfall within Florida since 1994. While tornadoes were not associated with all of the circulations (manual not algorithm defined), those which exhibited persistent and relatively strong rotation did often correlate with touchdowns (Table 1). Similarities between tornado- producing circulations will be discussed in Section 7. Contained within this document are 0.5 degree base reflectivity and storm relative velocity images from the Melbourne (KMLB; Gordon, Erin, Josephine, Georges), Jacksonville (KJAX; Allison), and Eglin Air Force Base (KEVX; Opal) WSR-88D sites. Arrows on the images indicate cells which produced persistent rotation. 2. TC GORDON (94) MESO CHARACTERISTICS KMLB radar surveillance of TC Gordon revealed two occurrences of mesoscale families (first period not shown). -

Quasi-Linear Convective System Mesovorticies and Tornadoes

Quasi-Linear Convective System Mesovorticies and Tornadoes RYAN ALLISS & MATT HOFFMAN Meteorology Program, Iowa State University, Ames ABSTRACT Quasi-linear convective system are a common occurance in the spring and summer months and with them come the risk of them producing mesovorticies. These mesovorticies are small and compact and can cause isolated and concentrated areas of damage from high winds and in some cases can produce weak tornadoes. This paper analyzes how and when QLCSs and mesovorticies develop, how to identify a mesovortex using various tools from radar, and finally a look at how common is it for a QLCS to put spawn a tornado across the United States. 1. Introduction Quasi-linear convective systems, or squall lines, are a line of thunderstorms that are Supercells have always been most feared oriented linearly. Sometimes, these lines of when it has come to tornadoes and as they intense thunderstorms can feature a bowed out should be. However, quasi-linear convective systems can also cause tornadoes. Squall lines and bow echoes are also known to cause tornadoes as well as other forms of severe weather such as high winds, hail, and microbursts. These are powerful systems that can travel for hours and hundreds of miles, but the worst part is tornadoes in QLCSs are hard to forecast and can be highly dangerous for the public. Often times the supercells within the QLCS cause tornadoes to become rain wrapped, which are tornadoes that are surrounded by rain making them hard to see with the naked eye. This is why understanding QLCSs and how they can produce mesovortices that are capable of producing tornadoes is essential to forecasting these tornadic events that can be highly dangerous. -

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE of DUPAGE METEOROLOGY Focus on Anticipating and Spotting

Storm Spotting – Solidifying the Basics PROFESSOR PAUL SIRVATKA COLLEGE OF DUPAGE METEOROLOGY HTTP://WEATHER.COD.EDU Focus on Anticipating and Spotting • What do you look for? • What will you actually see? • Can you identify what is going on with the storm? Is Gilbert married? Hmmmmm….rumor has it….. Its all about the updraft! Not that easy! • Various types of storms and storm structures. • A tornado is a “big sucky • Obscuration of important thing” and underneath the features make spotting updraft is where it forms. difficult. • So find the updraft! • The closer you are to a storm the more difficult it becomes to make these identifications. Conceptual models Reality is much harder. Basic Conceptual Model Sometimes its easy! North Central Illinois, 2-28-17 (Courtesy of Matt Piechota) Other times, not so much. Reality usually is far more complicated than our perfect pictures Rain Free Base Dusty Outflow More like reality SCUD Scattered Cumulus Under Deck Sigh...wall clouds! • Wall clouds help spotters identify where the updraft of a storm is • Wall clouds may or may not be present with tornadic storms • Wall clouds may be seen with any storm with an updraft • Wall clouds may or may not be rotating • Wall clouds may or may not result in tornadoes • Wall clouds should not be reported unless there is strong and easily observable rotation noted • When a clear slot is observed, a well written or transmitted report should say as much Characteristics of a Tornadic Wall Cloud • Surface-based inflow • Rapid vertical motion (scud-sucking) • Persistent • Persistent rotation Clear Slot • The key, however, is the development of a clear slot Prof. -

Mt417 – Week 10

Mt417 – Week 10 Use of radar for severe weather forecasting Single Cell Storms (pulse severe) • Because the severe weather happens so quickly, these are hard to warn for using radar • Main Radar Signatures: i) Maximum reflectivity core developing at higher levels than other storms ii) Maximum top and maximum reflectivity co- located iii) Rapidly descending core iv) pure divergence or convergence in velocity data Severe cell has its max reflectivity core higher up Z With a descending reflectivity core, you’d see the reds quickly heading down toward the ground with each new scan (typically around 5 minutes apart) Small Scale Winds - Divergence/Convergence - Divergent Signature Often seen at storm top level or near the Note the position of the radar relative to the ground at close velocity signatures. This range to a pulse type is critical for proper storm interpretation of the small scale velocity data. Convergence would show colors reversed Multicells (especially QLCSs– quasi-linear convective systems) • Main Radar Signatures i) Weak echo region (WER) or overhang on inflow side with highest top for the multicell cluster over this area (implies very strong updraft) ii) Strong convergence couplet near inflow boundary Weak Echo Region (left: NWS Western Region; right: NWS JETSTREAM) • Associated with the updraft of a supercell thunderstorm • Strong rising motion with the updraft results in precipitation/ hail echoes being shifted upward • Can be viewed on one radar surface (left) or in the vertical (schematic at right) Crude schematic of -

An Examination of the Mechanisms and Environments Supportive of Bow Echo Mesovortex Genesis

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department Atmospheric Sciences of 5-2013 An Examination of the Mechanisms and Environments Supportive of Bow Echo Mesovortex Genesis George Limpert University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss Part of the Atmospheric Sciences Commons, and the Meteorology Commons Limpert, George, "An Examination of the Mechanisms and Environments Supportive of Bow Echo Mesovortex Genesis" (2013). Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 39. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geoscidiss/39 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations & Theses in Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AN EXAMINATION OF THE MECHANISMS AND ENVIRONMENTS SUPPORTIVE OF BOW ECHO MESOVORTEX GENESIS by George Limpert A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Under the Supervision of Professor Adam Houston Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 AN EXAMINATION OF THE MECHANISMS AND ENVIRONMENTS SUPPORTIVE OF BOW ECHO MESOVORTEX GENESIS George Limpert, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Adam Houston Low-level mesovortices are associated with enhanced surface wind gusts and high-end wind damage in quasi-linear thunderstorms. Although damage associated with mesovortices can approach that of moderately strong tornadoes, skill in forecasting mesovortices is low. -

A Revised Tornado Definition and Changes in Tornado Taxonomy

1256 WEATHER AND FORECASTING VOLUME 29 A Revised Tornado Definition and Changes in Tornado Taxonomy ERNEST M. AGEE Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana (Manuscript received 4 June 2014, in final form 30 July 2014) ABSTRACT The tornado taxonomy presented by Agee and Jones is revised to account for the new definition of a tor- nado provided by the American Meteorological Society (AMS) in October 2013, resulting in the elimination of shear-driven vortices from the taxonomy, such as gustnadoes and vortices in the eyewall of hurricanes. Other relevant research findings since the initial issuance of the taxonomy are also considered and in- corporated, where appropriate, to help improve the classification system. Multiple misoscale shear-driven vortices in a single tornado event, when resulting from an inertial instability, are also viewed to not meet the definition of a tornado. 1. Introduction and considerations from a cumuliform cloud, and often visible as a funnel cloud and/or circulating debris/dust at the ground.’’ In The first proposed tornado taxonomy was presented view of the latest definition, a few changes are warranted by Agee and Jones (2009, hereafter AJ) consisting of in the AJ taxonomy. Considering the roles played by three types and 15 species, ranging from the type I buoyancy and shear on a variety of spatial and temporal (potentially strong and violent) tornadoes produced by scales (from miso to meso to synoptic), coupled with the the classic supercell, to the more benign type III con- requirement in the latest definition that a tornado must vective and shear-driven vortices such as landspouts and be pendant from a cumuliform cloud, it is necessary to gustnadoes. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

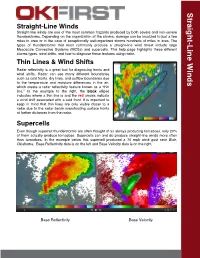

Straig H T-Line W in Ds

Straight Straight-Line Winds Straight-line winds are one of the most common hazards produced by both severe and non-severe thunderstorms. Depending on the organization of the storms, damage can be localized to just a few miles in area or in the case of exceptionally well-organized storms hundreds of miles in area. The - types of thunderstorms that most commonly produce a straight-line wind threat include large Line Winds Mesoscale Convective Systems (MCSs) and supercells. This help page highlights these different storms types, wind shifts, and how to diagnose these features using radar. Thin Lines & Wind Shifts Radar reflectivity is a great tool for diagnosing fronts and wind shifts. Radar can see many different boundaries such as cold fronts, dry lines, and outflow boundaries due to the temperature and moisture differences in the air, which create a radar reflectivity feature known as a “thin line.” In the example to the right, the black ellipse indicates where a thin line is and the red arrows indicate a wind shift associated with a cold front. It is important to keep in mind that thin lines are only visible closer to a radar due to the radar beam overshooting surface fronts at farther distances from the radar. Supercells Even though supercell thunderstorms are often thought of as always producing tornadoes, only 20% of them actually produce tornadoes. Supercells can and do produce straight-line winds more often than tornadoes. In the example below this supercell produced a 70 mph wind gust near Blair, Oklahoma. Base Reflectivity data is on the left and Base Velocity data is on the right. -

Mcss Squall Lines Bow Echoes Mesoscale Convective Complexes

Overview Introduction to MCSs Squall Lines Bow Echoes Mesoscale Convective Complexes Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Definition Mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) refer to all organized convective systems larger than supercells Some classic convective system types include: squall lines, bow echoes, and mesoscale convective complexes (MCCs) MCSs occur worldwide and year-round In addition to the severe weather produced by any given cell within the MCS, the systems can generate large areas of heavy rain and/or damaging winds Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Examples Hawaiian Bow Echo Dryline Squall line in Texas Note the scale difference! Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Examples cont. MCC initiating over Nebraska Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Synoptic Patterns Favorable conditions conducive to severe MCSs and MCCs often occur with identifiable synoptic patterns Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Environmental Factors Both synoptic and mesoscale features can significantly impact MCS structure and evolution Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Importance of Shear For a given CAPE, the strength and longevity of an MCS increases with increasing depth and strength of the vertical wind shear For midlatitude environments we can classify Sfc. to 2-3 km AGL shear strengths as weak <10 m/s, mod 10-18 m/s, & strong >18 m/s In general, the higher the LFC, the more low- level shear is required for a system’s cold pool to continue initiating convection Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Which Shear Matters? It is the component of low-level vertical wind shear perpendicular to the line that is most critical for controlling squall line structure & evolution Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Squall Lines Title goes here for lesson February 2002 Squall Line Definition A squall line is any line of convective cells.