A Biogeographic Study of Intermountain Leeches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Article Genetic Diversity of Freshwater Leeches in Lake Gusinoe (Eastern Siberia, Russia)

Hindawi Publishing Corporation e Scientific World Journal Volume 2014, Article ID 619127, 11 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/619127 Research Article Genetic Diversity of Freshwater Leeches in Lake Gusinoe (Eastern Siberia, Russia) Irina A. Kaygorodova,1 Nadezhda Mandzyak,1 Ekaterina Petryaeva,1,2 and Nikolay M. Pronin3 1 Limnological Institute, 3 Ulan-Batorskaja Street, Irkutsk 664033, Russia 2 Irkutsk State University, 5 Sukhe-Bator Street, Irkutsk 664003, Russia 3 Institute of General and Experimental Biology, 6 Sakhyanova Street, Ulan-Ude 670047, Russia Correspondence should be addressed to Irina A. Kaygorodova; [email protected] Received 30 July 2014; Revised 7 November 2014; Accepted 7 November 2014; Published 27 November 2014 Academic Editor: Rafael Toledo Copyright © 2014 Irina A. Kaygorodova et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The study of leeches from Lake Gusinoe and its adjacent area offered us the possibility to determine species diversity. Asa result, an updated species list of the Gusinoe Hirudinea fauna (Annelida, Clitellata) has been compiled. There are two orders and three families of leeches in the Gusinoe area: order Rhynchobdellida (families Glossiphoniidae and Piscicolidae) and order Arhynchobdellida (family Erpobdellidae). In total, 6 leech species belonging to 6 genera have been identified. Of these, 3 taxa belonging to the family Glossiphoniidae (Alboglossiphonia heteroclita f. papillosa, Hemiclepsis marginata,andHelobdella stagnalis) and representatives of 3 unidentified species (Glossiphonia sp., Piscicola sp., and Erpobdella sp.) have been recorded. The checklist gives a contemporary overview of the species composition of leeches and information on their hosts or substrates. -

Distribution of the Ribbon Leech in North Dakota

109 Distribution of the Ribbon Leech in North Dakota CHRISTOPHER M. PENNUTOI and MALCOLM G. BUTLER Department of Zoology, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58105 ABSTRACT-The distribution of the ribbon leech, NepMlopsis obscwra, was examined in the Central Lowland and Missouri Coteau regions of North Dakota. The leech was found in 12 of3S ponds sampled during a two-year period. Leeches were trapped with throated metal cans and burlap sacks baited with frozen fish parts. Leech ocamence was positively correlated with maximum depth, mean conductivity, and percent littoral rock cover. Leech occurrence was not correlated with surface area or latiwde. Ponds containing N. obscwra were characterized by maximum depths greater than or equal to 1.0 m, mean conductivity values between 500 and 2300 uS/em', and some measurable littoral rock cover. Investiga tions concerning all life cycle anributes ofleech populations should be pursued in North Dakota to assist resource managers in establishing harvest policy for this important bait source. Key words: NepMlopsis obscwra, conductivity, maximum depth, prairie wetlands, ribbon leech The ribbon leech (Nephelopsis obscura Verrill; Hirudinea: Erpobdellidae) is an importantfish baitin the upper Midwestprizedby walleye and bass anglers. This leech occurs in ponds throughout the North Central and northern Rocky Mountain states in the U.S. and Canada (Herrmann 1970a, Klemm 1985). Collinsetal. (1981) suggested that Type III and IV wetlands with a silty bottom and no sport fish are ideal leech habitats in Minnesota. This leech has a semelparous, but potentially iteroparous, life cycle and attains a maximum fresh weight of 150-1200 mg, depending on geographic region (Davies and Everett 1977, Davies 1978, Linton et al. -

Fish Surveys on the Uinta & Wasatch-Cache National

FISH SURVEYS ON THE UINTA & WASATCH-CACHE NATIONAL FORESTS 1995 By Paul K Cowley Forest Fish Biologist Uinta and Wasatch-Cache National Forest January 22, 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................... i LIST OF FIGURES ....................... iii LIST OF TABLES ....................... v INTRODUCTION ........................ 1 METHODS ........................... 1 RESULTS ........................... 4 Weber River Drainage ................. 5 Ogden River ................... 5 Slate Creek ................... 8 Yellow Pine Creek ................ 10 Coop Creek .................... 10 Shingle Creek .................. 13 Great Salt Lake Drainage ............... 16 Indian Hickman Creek ............... 16 American Fork River .................. 16 American Fork River ............... 16 Provo River Drainage ................. 20 Provo Deer Creek ................. 20 Right Fork Little Hobble Creek .......... 20 Rileys Canyon .................. 22 Shingle Creek .................. 22 North Fork Provo River .............. 22 Boulder Creek .................. 22 Rock Creek .................... 24 Soapstone Creek ................. 24 Spring Canyon .................. 27 Cobble Creek ................... 27 Hobble Creek Drainage ................. 29 Right Fork Hobble Creek ............. 29 Spanish Fork River Drainage .............. 29 Bennie Creek ................... 29 Nebo Creek ................... 29 Tie Fork ..................... 32 Salt Creek Drainage .................. 32 Salt Creek .................... 32 Price River Drainage ................ -

Arhynchobdellida (Annelida: Oligochaeta: Hirudinida): Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30 (2004) 213–225 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Arhynchobdellida (Annelida: Oligochaeta: Hirudinida): phylogenetic relationships and evolution Elizabeth Bordaa,b,* and Mark E. Siddallb a Department of Biology, Graduate School and University Center, City University of New York, New York, NY, USA b Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA Received 15 July 2003; revised 29 August 2003 Abstract A remarkable diversity of life history strategies, geographic distributions, and morphological characters provide a rich substrate for investigating the evolutionary relationships of arhynchobdellid leeches. The phylogenetic relationships, using parsimony anal- ysis, of the order Arhynchobdellida were investigated using nuclear 18S and 28S rDNA, mitochondrial 12S rDNA, and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I sequence data, as well as 24 morphological characters. Thirty-nine arhynchobdellid species were selected to represent the seven currently recognized families. Sixteen rhynchobdellid leeches from the families Glossiphoniidae and Piscicolidae were included as outgroup taxa. Analysis of all available data resolved a single most-parsimonious tree. The cladogram conflicted with most of the traditional classification schemes of the Arhynchobdellida. Monophyly of the Erpobdelliformes and Hirudini- formes was supported, whereas the families Haemadipsidae, Haemopidae, and Hirudinidae, as well as the genera Hirudo or Ali- olimnatis, were found not to be monophyletic. The results provide insight on the phylogenetic positions for the taxonomically problematic families Americobdellidae and Cylicobdellidae, the genera Semiscolex, Patagoniobdella, and Mesobdella, as well as genera traditionally classified under Hirudinidae. The evolution of dietary and habitat preferences is examined. Ó 2003 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. -

Echo Dam, Weber River Project Summit County, Utah, Safety of Dams Modification, Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact PRO-EA-05-003

Echo Dam, Weber River Project Summit County, Utah, Safety of Dams Modification, Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact PRO-EA-05-003 Weber River Project, Summit County, Utah Upper Colorado Region Provo Area Office U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Provo Area Office Provo, Utah September 2009 Mission Statements The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to Indian Tribes and our commitments to island communities. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Echo Dam, Weber River Project Summit County, Utah, Safety of Dams Modification, Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact PRO-EA-05-003 Weber River Project, Summit County, Utah Upper Colorado Region Provo Area Office Contact Person W. Russ Findlay Provo Area Office 302 East 1860 South Provo, Utah 84606 801-379-1084 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Provo Area Office Provo, Utah September 2009 Contents Page Chapter 1 – Need for Proposed Action and Background.................................. 1 1.1 Introduction........................................................................................... 1 1.2 Dam Safety Program Overview............................................................ 1 1.2.1 Safety of Dams NEPA Compliance Requirements..................... 2 1.3 Purpose of and Need for the Proposed Action...................................... 2 1.4 Description of Echo Dam and Reservior .............................................. 2 1.4.1 Echo Dam.................................................................................... 3 1.4.2 Echo Reservoir............................................................................ 5 1.4.3 Normal Operations..................................................................... -

Aquatic Biological Resources Technical Report

Northern Integrated Supply Project Environmental Impact Statement Aquatic Biological Resources Technical Report Prepared for: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Omaha District March 2008 Prepared by: GEI Consultants, Inc. Chadwick Ecological Division 5575 South Sycamore Street, Suite 101 Littleton, CO 80120 CONTENTS 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................1 1.1. Northern Integrated Supply Project ...................................................................1 1.2. No Action Alternative ........................................................................................1 1.3. Group 1—Southern Group .................................................................................2 1.3.1. Erie .........................................................................................................3 1.3.2. Lafayette ................................................................................................3 1.3.3. Lefthand Water District .........................................................................3 1.3.4. No Action Alternative for Southern Group ...........................................3 1.4. Group 2—Northern Group .................................................................................3 1.4.1. Eaton ......................................................................................................4 1.4.2. Severance ...............................................................................................4 1.4.3. -

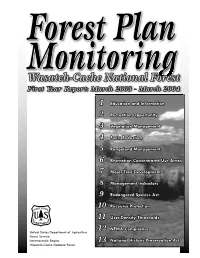

Forest Plan Monitoringmonitoring Wasatch-Cache National Forest First Year Report: March 2003 - March 2004

Forest Plan MonitoringMonitoring Wasatch-Cache National Forest First Year Report: March 2003 - March 2004 1 Education and Information 2 Recreation Opportunity 3 Vegetation Management 4 Fuels Reduction 5 Rangeland Management 6 Recreation Concentrated Use Areas 7 Major Trail Development 8 Management Indicators 9 Endangered Species Act 10 Resource Protection 11 User Density Thresholds 12 NFMA Compliance United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Intermountain Region 13 National Historic Preservation Act Wasatch-Cache National Forest A Note from the Forest Supervisor ANote from the Forest Supervisor The Revised Forest Plan for the Wasatch-Cache National Forest was approved March 19, 2003. An important part of keeping the Plan current and adapting it as conditions change or as we learn from experience is monitoring. The Revised Plan Monitoring and Evalu- ation section (Chapter 4, pg. 4-105) outlines the program for follow- ing up on important decisions made in the Plan. Last September we shared with you further steps or “protocols” for moving forward with this program. We have now been implementing this new Plan for more than a year and would like to share some of the results of the first year. In some cases it is too early to actually report on what we have accomplished in each area because the monitoring protocol requires more than a year. In other areas information has been collected as a baseline to track future trends. In the coming years, a collective review of several years of information will be evaluated to determine if our management is actually moving the forest toward desired conditions. -

A History of Morgan County, Utah Centennial County History Series

610 square miles, more than 90 percent of which is privately owned. Situated within the Wasatch Mountains, its boundaries defined by mountain ridges, Morgan Countyhas been celebrated for its alpine setting. Weber Can- yon and the Weber River traverse the fertile Morgan Valley; and it was the lush vegetation of the pristine valley that prompted the first white settlers in 1855 to carve a road to it through Devils Gate in lower Weber Canyon. Morgan has a rich historical legacy. It has served as a corridor in the West, used by both Native Americans and early trappers. Indian tribes often camped in the valley, even long after it was settled by Mormon pioneers. The southern part of the county was part of the famed Hastings Cutoff, made notorious by the Donner party but also used by Mormon pioneers, Johnston's Army, California gold seekers, and other early travelers. Morgan is still part of main routes of traffic, including the railroad and utility lines that provide service throughout the West. Long known as an agricultural county, the area now also serves residents who commute to employment in Wasatch Front cities. Two state parks-Lost Creek Reservoir and East A HISTORY OF Morgan COUY~Y Linda M. Smith 1999 Utah State Historical Society Morgan County Commission Copyright O 1999 by Morgan County Commission All rights reserved ISBN 0-913738-36-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-61320 Map by Automated Geographic Reference Center-State of Utah Printed in the United States of America Utah State Historical Society 300 Rio Grande Salt Lake City, Utah 84 101 - 1182 Dedicated to Joseph H. -

Identification of Macroinvertebrate Samples for State E.P.A

I L L IN 0 I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. N6c Natural History Survey /9 Sr• Library ILLINOIS _-__ NATURAL HISTORY - SURVEY / "' 7 • womm Section of Faunistic Surveys and Insect Identification Technical Report IDENTIFICATION OF MACROINVERTEBRATE SAMPLES FOR STATE E. P. A. by- Donald W. Webb T^U,.'I, 7 T"T74- , .,a - JUo nL Un UL.,AA.A.=&.. Larry M. Page Mark J. Wetzel Warren U. Brigham LIST OF IDENTIFIERS Dr. W. U. Brigham: Coleoptera. Dr. L. M. Page: Amphipoda, Decapoda, and Isopoda Dr. J. U. Unzicker: Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera Dr. D. W. Webb: Coleoptera, Diptera, Hemiptera, Megaloptera, Mollusca, and Odonata Mr. M. Wetzel: Hirudinea, Nematoda, Nematomorpha, Oligochaeta, and Turbellaria, i0 LIST OF TAXA TURBELLARIA OLIGOCHAETA Branchiobdellida Branchiobdellidae Lumbricul ida Lumbriculidae Haplotaxida Lumbricidae Naididae Chaetogaster sp. Dero digitata Dero furcata Dero pectinata Nais behningi Nais cacnunis Nais pardalis Ophidonais serpentina Paranais frici Tubificidae Branchiura sowerbyi Ilyodrilus templetoni Limnodrilus sp. Limnodrilus cervix Limnodrilus claparedeianus Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri STul bifex tubifex HIRUDINEA Rhynchobdellida Glossiphoniidae Helobdella stagnalis Helobdella triserialis Placobdella montifera Placobdella multilineata Placobdella ornata Pharyngobdellida Erpobdellidae Erpobdella punctata NEM AlDA NEATOMORPHA ISOPODA Asellidae Caecidotea intermedia Lirceus sp. AMPHIPODA Gammaridae -

Upper Weber Marion Kamas Francis Woodland Uinta Mountains Peoa

Kamas Driving Guide 2008 3/17/08 9:34 AM Page 1 10 19. Duchesne Tunnel. Built 1940 - 1952. 32 Upper Weber This 6 mile tunnel brings water from the 7. Smith and Morehouse Reservoir. Campground, Duchesne River to the Provo River. Milepost 18, Hwy 150. Closed in winter. 300 North boat ramp, picnic area, mountain access. 12 miles from Oakley. Hwy 213. 20. Uinta Falls. Milepost 12.6, Hwy 150. Closed in winter. 200 North Kamas 8. Holiday Park. The Headwaters of the 21. Trial Lake High Mountain Dams, & John est 100 North Weber River. Grix Cabin. Lakes built with pack animals W and 2-wheeled carts between 1910 & 1940. 200 Center St. Cabin built 1922 - 1925 during 11 The valley’s elevation made 32 100 South expansion of Trial Lake. Closed in winter. 12 Marion farming difficult, but the 31 22. Bald Mountain Pass. High point (10,678 ft). 200 South 150 248 To Uintas 9. Original LDS Church. towns soon found a cash crop Blazzard Lumber in Kamas 30 Views into the Uinta Wilderness and of Bald est 300 South Built 1910-1914. Now Mt. (11,947) Hayden Peak (12,473), Mt in timber. Great forest of pine covered the mountains Cover photo: Janet Thimmes “Traffic on Main Street in Kamas” W 24 Kamas Valley Co-op. Agassiz (12,429). Milepost 29•B, Hwy 150. and canyons above the towns. Timber camps were 100 400 South Note the arched windows. Closed in winter. erected near the headwaters of Beaver Creek, the Provo Milepost 15.9, Hwy 32. -

Chapter 32: Response to Comments

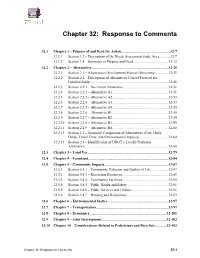

Chapter 32: Response to Comments 32.1 Chapter 1 – Purpose of and Need for Action ...................................................... 32-7 32.1.1 Section 1.2 – Description of the Needs Assessment Study Area ............ 32-7 32.1.2 Section 1.4 – Summary of Purpose and Need ....................................... 32-12 32.2 Chapter 2 – Alternatives ..................................................................................... 32-29 32.2.1 Section 2.1 – Alternatives Development Process (Screening) .............. 32-29 32.2.2 Section 2.2 – Description of Alternatives Carried Forward for Detailed Study ....................................................................................... 32-46 32.2.3 Section 2.2.1 – No-Action Alternative .................................................. 32-51 32.2.4 Section 2.2.2 – Alternative A1 .............................................................. 32-51 32.2.5 Section 2.2.3 – Alternative A2 .............................................................. 32-53 32.2.6 Section 2.2.4 – Alternative A3 .............................................................. 32-53 32.2.7 Section 2.2.5 – Alternative A4 .............................................................. 32-55 32.2.8 Section 2.2.6 – Alternative B1 .............................................................. 32-55 32.2.9 Section 2.2.7 – Alternative B2 .............................................................. 32-59 32.2.10 Section 2.2.8 – Alternative B3 .............................................................. 32-59 -

An All-Taxa Biodiversity Inventory of the Huron Mountain Club

AN ALL-TAXA BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY OF THE HURON MOUNTAIN CLUB Version: August 2016 Cite as: Woods, K.D. (Compiler). 2016. An all-taxa biodiversity inventory of the Huron Mountain Club. Version August 2016. Occasional papers of the Huron Mountain Wildlife Foundation, No. 5. [http://www.hmwf.org/species_list.php] Introduction and general compilation by: Kerry D. Woods Natural Sciences Bennington College Bennington VT 05201 Kingdom Fungi compiled by: Dana L. Richter School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 DEDICATION This project is dedicated to Dr. William R. Manierre, who is responsible, directly and indirectly, for documenting a large proportion of the taxa listed here. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 SOURCES 7 DOMAIN BACTERIA 11 KINGDOM MONERA 11 DOMAIN EUCARYA 13 KINGDOM EUGLENOZOA 13 KINGDOM RHODOPHYTA 13 KINGDOM DINOFLAGELLATA 14 KINGDOM XANTHOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHRYSOPHYTA 15 KINGDOM CHROMISTA 16 KINGDOM VIRIDAEPLANTAE 17 Phylum CHLOROPHYTA 18 Phylum BRYOPHYTA 20 Phylum MARCHANTIOPHYTA 27 Phylum ANTHOCEROTOPHYTA 29 Phylum LYCOPODIOPHYTA 30 Phylum EQUISETOPHYTA 31 Phylum POLYPODIOPHYTA 31 Phylum PINOPHYTA 32 Phylum MAGNOLIOPHYTA 32 Class Magnoliopsida 32 Class Liliopsida 44 KINGDOM FUNGI 50 Phylum DEUTEROMYCOTA 50 Phylum CHYTRIDIOMYCOTA 51 Phylum ZYGOMYCOTA 52 Phylum ASCOMYCOTA 52 Phylum BASIDIOMYCOTA 53 LICHENS 68 KINGDOM ANIMALIA 75 Phylum ANNELIDA 76 Phylum MOLLUSCA 77 Phylum ARTHROPODA 79 Class Insecta 80 Order Ephemeroptera 81 Order Odonata 83 Order Orthoptera 85 Order Coleoptera 88 Order Hymenoptera 96 Class Arachnida 110 Phylum CHORDATA 111 Class Actinopterygii 112 Class Amphibia 114 Class Reptilia 115 Class Aves 115 Class Mammalia 121 INTRODUCTION No complete species inventory exists for any area.