The Hero with No Face: an Appalachian Narrative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Other Side of the Monument: Memory, Preservation, and the Battles of Franklin and Nashville

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MONUMENT: MEMORY, PRESERVATION, AND THE BATTLES OF FRANKLIN AND NASHVILLE by JOE R. BAILEY B.S., Austin Peay State University, 2006 M.A., Austin Peay State University, 2008 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2015 Abstract The thriving areas of development around the cities of Franklin and Nashville in Tennessee bear little evidence of the large battles that took place there during November and December, 1864. Pointing to modern development to explain the failed preservation of those battlefields, however, radically oversimplifies how those battlefields became relatively obscure. Instead, the major factor contributing to the lack of preservation of the Franklin and Nashville battlefields was a fractured collective memory of the two events; there was no unified narrative of the battles. For an extended period after the war, there was little effort to remember the Tennessee Campaign. Local citizens and veterans of the battles simply wanted to forget the horrific battles that haunted their memories. Furthermore, the United States government was not interested in saving the battlefields at Franklin and Nashville. Federal authorities, including the War Department and Congress, had grown tired of funding battlefields as national parks and could not be convinced that the two battlefields were worthy of preservation. Moreover, Southerners and Northerners remembered Franklin and Nashville in different ways, and historians mainly stressed Eastern Theater battles, failing to assign much significance to Franklin and Nashville. Throughout the 20th century, infrastructure development encroached on the battlefields and they continued to fade from public memory. -

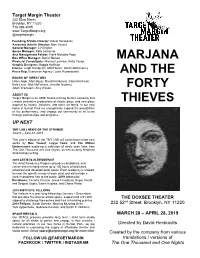

Marjana Program

Target Margin Theater 232 52nd Street Brooklyn, NY 11220 718-398-3095 www.TargetMargin.org @targetmargin Founding Artistic Director: David Herskovits Associate Artistic Director: Moe Yousuf General Manager: Liz English Space Manager: Kelly Lamanna Arts Management Fellow: Frank Nicholas Poon Box Office Manager: Daniel Nelson MARJANA Financial Consultants: Michael Levinton, Patty Taylor Graphic Designer: Maggie Hoffman Interns: Leigh Honigman, Matt Hunter, Sarah McEneaney Press Rep: Everyman Agency / John Wyszniewski AND THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Hilary Alger, Matt Boyer, David Herskovits, Dana Kirchman, Kate Levin, Matt McFarlane, Jennifer Nadeau, Adam Weinstein, Amy Wilson. FORTY ABOUT US Target Margin is an OBIE Award-winning theater company that creates innovative productions of classic plays, and new plays THIEVES inspired by history, literature, and other art forms. In our new home in Sunset Park we energetically expand the possibilities of live performance, and engage our community at all levels through partnerships and programs. UP NEXT TMT LAB | NEWS OF THE STRANGE June 6 – June 23, 2019 This year’s edition of the TMT LAB will commission three new works by Moe Yousuf, Leyya Tawil, and The Million Underscores exploring a collection of rarely seen tales from The One Thousand and One Nights, as well as early Medieval Arab fantasy writing. 2019 ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE The Artist Residency Program provides established, mid- career and emerging artists up to 100 hours of dedicated rehearsal and developmental space. Each residency is shaped to meet the specific needs of each artist and will include a work-in-progress free to the public. 2019 Artists-in- Residence: Tanisha Christie, Jesse Freedman, Sugar Vendil, and Deepali Gupta, Sarah Hughes, and Chana Porter. -

Daily Record Article for January 10 2004 00050575 .DOC

attorneys at law . a professional corporation Down Like the Titantic By: Jim Astrachan Late last month the Second Circuit Court of Appeals sunk the copyright infringement claim of an aspiring songwriter who said he had written the Academy Award-winning theme song from the blockbuster movie, Titanic. It kept afloat his claim that Fox Film Music had copied the same song which was released as, Lonely Grill, by the band Lonestar. With summary judgment granted to the Titanic songwriters, but denied to Fox Film, this case points out the need for every company to adopt a policy either rejecting unsolicited submissions of anything even remotely creative, or requiring the submitter to sign an agreement before the submission is even read. John Jorgansen, the songwriter, claimed that the hit song sung by Celine Dion and written by James Horner and Will Jennings, My Heart Will Go On, infringed his song, Long Lost Lover. He also claimed Lonely Grill infringed, Long Lost Lover. Jorgansen had sent mass mailings of his song throughout the industry, and he claimed that his song was substantially similar to those recorded by Ms. Dion and Lonestar. He alleged Defendants had copied his songs. 99001.003/50575 1 To succeed in a copyright case, a plaintiff must prove ownership of the copyright and copying. Registration of the work is prima facie evidence of ownership; copying can be proved by direct evidence or circumstantial evidence. Most cases are made on circumstantial evidence because there are not often witnesses to the occurrence. A showing of access and substantial similarity between the two works will meet a plaintiff's burden of proof in the absence of direct evidence. -

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Marker

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Markers Installed as of 6/9/11 Note: Some sites include multiple markers. BENTON COUNTY Fighting on the Tennessee River: located at Birdsong Marina, 225 Marina Rd., Hwy 191 N., Camden, TN 38327. During the Civil War, several engagements occurred along the strategically important Tennessee River within about five miles of here. In each case, cavalrymen engaged naval forces. On April 26, 1863, near the mouth of the Duck River east of here, Confederate Maj. Robert M. White’s 6th Texas Rangers and its four-gun battery attacked a Union flotilla from the riverbank. The gunboats Autocrat, Diana, and Adams and several transports came under heavy fire. When the vessels drove the Confederate cannons out of range with small-arms and artillery fire, Union Gen. Alfred W. Ellet ordered the gunboats to land their forces; signalmen on the exposed decks “wig-wagged” the orders with flags. BLOUNT COUNTY Maryville During the Civil War: located at 301 McGee Street, Maryville, TN 37801. During the antebellum period, Blount County supported abolitionism. In 1822, local Quakers and other residents formed an abolitionist society, and in the decades following, local clergymen preached against the evils of slavery. When the county considered secession in 1861, residents voted to remain with the Union, 1,766 to 414. Fighting directly touched Maryville, the county seat, in August 1864. Confederate Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalrymen attacked a small detachment of the 2nd Tennessee Infantry (U.S.) under Lt. James M. Dorton at the courthouse. The Underground Railroad: located at 503 West Hill Ave., Friendsville, TN 37737. -

Wedding Processionals & Recessionals Sacred Music Jewish

“ANTHEM” 1 Song List for Ensembles or Soloists Please note: If you don’t see what you’re looking for, please ask. We have access to far more music than we could ever list here! Wedding Processionals & Recessionals Bach, Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Pachelbel, Canon in D Beethoven, Ode to Joy Purcell, Trumpet Tune Brahms, Theme from 1st Symphony Mussorgsky, Promenade from Pictures at an Exhibition Clarke, Trumpet Voluntary Mendelssohn, Wedding March (traditional recessional) Handel, Hornpipe from Water Music Vivaldi, Spring Handel, La Rejouissance Wagner, Bridal Chorus (traditional processional) Sacred Music Our library contains all standard hymns and spirituals. In addition to these, we recommend the following selections for sacred services and ceremonies. Amazing Grace Beethoven, Ode to Joy Bach, Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring Bradbury/Thrupp, Savior, Like a Shepherd Lead Us Bach, Sheep May Safely Graze Franck, Panis Angelicus Bach/Gounod, Ave Maria Jewish Ceremony and Reception Erev Shel Shoshanim K’shoshana Ben Hachochim Dodi Li Hitragut Bruchim Habaim Jerusalem of Gold Mi Adir Wedding March Sheva Brachot Chorshat Ha’ekaliptus K’var Achare Chatsot Eli Eli Y’did Nefesh Hakotel Celtic and Gaelic Ireland National Anthem Maids of Mourne Shore Carolan’s Concerto My Love is Gone to Sea Countess of Sutherland Pretty Girl Milking Her Cow Danny Boy Rakes of Mallow The Flower Of The Quern Road to Lisdoonvarna Garton Mother’s Lullaby Si Beag Si Mor Give Me Your Hand Timour the Tartar Sor Blanca Maria Yell Yell Last Rose of Summer Jigs, Reels, Hornpipes, -

Biography -- Printable Version

Biography -- Printable Version Peter Wolf's Historical Biography Written & Researched by Bryan Wiser, and Sheila Warren with Mimi Fox. Born in New York City, Peter grew up in the Bronx during the mid-1950's in a small, three-room apartment where he lived with his parents, older sister, two cats, dog and parakeet. For some time, Peter lived with his grandmother, an actress in New York City's Yiddish Theater. She and Peter had a strong bond, and she affectionately named him "Little Wolf" for his energetic and rambunctious ways. His father was a musician, vaudevillian and singer of light opera. Like Peter did years later, his father left home at age fourteen to join the Schubert Theater Touring Company with which he traveled the country performing light operas such as The Student Prince and Merry Widow. He had his own radio show called The Boy Baritone, which featured new songs from Tin Pan Alley, and was a member of the Robert Shaw Chorale. As a result of such artistic pursuits, Peter's father underwent long periods of unemployment that created a struggle to make financial ends meet. Peter's mother was an elegant and attractive woman who taught inner-city children in the South Bronx for 27 years. A political activist, union organizer and staunch civil rights advocate, she supported racial equality by attending many of the southern "freedom rides" and marches. Peter's older sister was also a teacher as well as a photographer who now works as an advocate for persons with disabilities. She continues her mother's tradition, often marching on Washington to support the rights of the disabled. -

Song Artist Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers All I Ask of You Andrew

Song Artist Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers All I Ask Of You Andrew Lloyd Webber Always On My Mind Wayne Thomps Angel Sarah Mclachlan As Long As You Love Me Backstreet Boys Autumn Leaves Johnny Mercer Beautiful Christina Aguilera Because Of You Kelly Clarkson Bed Of Roses Bon Jovi Black Eyed Boy Texas Blowin’ In The Wind Bob Dylan Blue Moon Richard Rodgers Bring Him Home Claude Michel Schonberg Can You Read My Mind? John Williams, Leslie Bricusse Candle In The Wind Elton John Chasing Cars Snow Patrol CHASING PAVEMENTS Adele Climb Every Mountain Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II Close To You Carpenters Cockles and muscles Irish Air Come Away With Me Norah Jones Crazy Willie Nelson Cry Me A River Arthur Hamilton Dancing In The Dark Arthur Schwartz Danny Boy Londonderry Air, Traditional Irish Tune, Frederic Weatherly 1910 Don’t Know Why Norah Jones Don’t Speak No Doubt Durham Town Roger Whittaker Eternal Flame Bangles Evergreen Barbra Streisand Everlasting Love Gloria Estefan Fallen Lauren Wood Fallen Sarah McLachlan Fallin’ Alicia Keys Fields Of Gold Sting Fix You Coldplay Fly Me To The Moon Bart Howard Georgia On My Mind Hoagy Carmichael, Stuart Gorrell Girl, You'll Be A Woman Soon Neil Diamond Gymnopodie No.1 Satie Hallelujah Leonard Cohen Have I Told You Lately Van Morrison Hello Again Neil Diamond And Alan Lindgren, Neil Diamond Here Comes The Sun George Harrison Here There And Everywhere Paul McCartney, John Lennon Hero Mariah Carey Home Sweet Home Henry Bishop How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees How You Remind Me Nickelback I Believe -

CALENDAR COMPILED by COLLEEN ROMICK CLARK More Than 50 Vendors

PLEASE NOTE: Because of the developing coronavirus situation, JULY/AUGUST many of these planned events may have been postponed or 2021 canceled. Please seek updated information before traveling. COMPILED BY COLLEEN ROMICK CLARK CALENDAR more than 50 vendors. Live music, food vendors. AUG. 3 – National Night Out, downtown Sidney. NORTHWEST For questions, call Riverside Art Center at 419- Find us on the square for fun activities and food, all to 738-2352 or visit www.facebook.com/The-Moon- promote police-community partnerships; crime, drug, Market-101791285311307. and violence prevention; safety; and neighborhood JUL. 19–25 – Ottawa County Fair, Ottawa Co. Fgds., unity. 937-658-6945 or www.sidneyalive.org. 7870 W. St. Rte. 163, Oak Harbor. 419-898-1971 or www. AUG. 5–8 – Northwest Ohio Antique Machinery ottawacountyfair.org. Association Show, Hancock Co. Fgds., 1017 E. JUL. 24–25 – Van Wert Railroad Heritage Weekend, Sandusky St., Findlay. Tractors, engines, scooters, Van Wert Co. Fgds., 1055 S. Washington St., Van Wert, garden tractors, arts and crafts, consignment Sat. 10 a.m.–4 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.–3 p.m. $6; 2-day sales. This year we are hosting “The Gathering admission, $8; free for ages 12 and under. 200 vendor of the Orange,” the Allis Chalmers State tables with more than a dozen operating layouts and Show. 419-722-4698 or www.facebook.com/ THROUGH OCT. 9 – The Great Sidney Farmers displays. Food court and/or food trucks. Free stuff for NorthwestOhioAntiqueMachineryAssociation. Market, Courthouse Square, 109 S. Ohio Ave., every the kids! 260-760-1666 or [email protected]. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Do It Again": Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy's Margins Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4297q61r Author Baltimore, Samuel Dworkin Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Do It Again”: Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy’s Margins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Samuel Dworkin Baltimore 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Do It Again”: Comic Repetition, Participatory Reception and Gendered Identity on Musical Comedy’s Margins by Samuel Dworkin Baltimore Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Raymond Knapp, Chair This dissertation examines the ways that various subcultural audiences define themselves through repeated interaction with musical comedy. By foregrounding the role of the audience in creating meaning and by minimizing the “show” as a coherent work, I reconnect musicals to their roots in comedy by way of Mikhail Bakhtin’s theories of carnival and reduced laughter. The audiences I study are kids, queers, and collectors, an alliterative set of people whose gender identities and expressions all depart from or fall outside of the normative binary. Focusing on these audiences, whose musical comedy fandom is widely acknowledged but little studied, I follow Raymond Knapp and Stacy Wolf to demonstrate that musical comedy provides a forum for identity formation especially for these problematically gendered audiences. ii The dissertation of Samuel Dworkin Baltimore is approved. -

Configuration Recommendations for DOCSIS IP Transport of IP Video

CONFIGURATION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DOCSIS TRANSPORT OF MANAGED IP VIDEO SERVICE WILLIAM T. HANKS With special thanks to the following contributors: Jim Allen, Tom Cloonan, Michael Dehm, Amit Eshet, J.R. Flesch, Dwain Frieh, Will Jennings, Tal Laufer, Tushar Mathur, Dan Torbet, John Ulm, Bill Ward, and Ian Wheelock TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 4 TARGET AUDIENCE ........................................................................................ 4 VENDOR AND PRODUCT AGNOSTICISM ........................................................ 4 TECHNOLOGY BACKGROUND ........................................................................ 5 Video ServicEs ................................................................................................................ 5 LinEar Broadcast TV vs. On-dEmand Content ............................................................ 5 Television ChannEl ViewErship ................................................................................... 5 TV ChannEl ChangE ExpEctations ............................................................................... 8 InternEt Protocol (IP) ...................................................................................................... 8 ConnEction-OriEnted vs. ConnEctionlEss ................................................................... 8 IP Multicast – One StrEam, MultiplE DEstinations ..................................................... 9 IP Unicast – One StrEam, -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

Program Act Ii -- Opera Now

PROGRAM ACT II -- OPERA NOW ACT I -- OPERA THEN *# “Prayer,” Hansel and Gretal. Engelbert Humperdinck (1893). + “Summertime,” Porgy and Bess. *+ “Sous le dome epaias,” Lakme. Leo Delibes (1883). George Gershwin/DuBose Heyward (1935). * “Non so piu,” Le Nozze di Figaro. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1786). * “What a Movie,” Trouble in Tahiti. Leonard Bernstein. (1952). + “Ebben, ne andro lontana,” La Wally. Alfredo Catalani (1892). # “This Is My Beloved,” Kismet. Robert Wright/George Forrest (1953). #+ “Mira o Norma,” Norma. Vincenzo Bellini (1831). * “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina,” Evita. Charles Hart/Andrew Lloyd Webber (1987) * “Amour viens aider ma faiblesse,” Samson et Dalila. Camille Saint-Saens (1870). + “Il mio cuore va” (“My Heart Will Go On”), Titanic. James Horner/Will Jennings (1997). # “Quando m’en vo,” La Boheme. Giocomo Puccini (1896). *+# “The Prayer,” Quest for Camelot. Carole Bayer Sager/David Foster (1998). * “Habanera,” Carmen. Georges Bizet (1875). # # # # # # # # + “Io son l’umile ancella,” Adriana Lecouvrer. Francisco Cilea (1903). *+ “Barcarolle.” Les Contes d’Hoffman. Jacques Offenbach (1881). * Sung by Megan Thompson + Sung by Mary Mahoney Sung by Stacey Trenteseaux NOTE: At the conclusion of the concert, please allow the singers to leave the sanctuary INTERMISSION before you do so they may greet you in the narthex. ABOUT THE ARTISTS SUNDAY AFTERNOON ARTS AT COUNTRYSIDE Renee Deuvall, accompanist , graduated from Oberlin College and Conservatory with degrees in both vocal performance and art history. Her master’s degree in Slavic and East European languages, concentrating in Russian, brought her encore appearances in Vermont’s annual Slavic Music Festival. Relocating to Dunnellon presents in 1994, she served as organist for St.