Read the Full Itinerary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Color Correction for Underwater Photography

Color Correction for Underwater Photography By Vanessa Pateman Graphic Communication Department College of Liberal Arts California Polytechnic State University 2009 Table of Contents Chapter I - Purpose of Study ..............................................................1 Chapter II - Literature Review ............................................................3 Chapter III - Research Methods & Procedures ........................................13 Chapter IV - Results .......................................................................17 Chapter V - Conclusions ......................................................... ........27 Appendices: Appendix A - Color Attenuation Graphs.................................. ...29 Appendix B - Interview Q & A.................................................31 Appendix C - Color Attenuation Photographs...............................34 Citations......................................................................... ............36 Chapter I - Purpose of Study Imagine the lifestyle of underwater photographers. They are not only photographers; they are scuba divers. They travel the world to exotic places to explore and then record their findings of the marine world. They shoot in the ever-changing medium called seawater. The changing seasons and weather alter available light and underwater visibility. Sea creatures relocate and new species are discovered. Humankind’s curious nature drives people to document their discoveries to understand the sea, the world, everything, a little better. Underwater -

Marden Article.Indd

THE FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY SSAVEAVE WWRIGHTRIGHT EDUCATION ADVOCACY PRESERVATION The Luis And Ethel Marden House: BULLETIN Volume 18, Issue 3 Adventure in Restoration Summer 2008 By Susan H. Stafford of the Potomac in 1944, Luis and Ethel spotted the perfect hillside setting across the river in Virginia and promptly purchased the two-acre site. When they fi nally received the fi rst set of plans in 1952, the Mardens were not pleased. They felt that Wright had recycled a prairie house design that failed to meet their needs or take full advantage of the site. Wright had done his initial drawings from topographical maps and photographs, and only experienced the full drama of the site much later. After more planning delays caused by Luis’ extensive travel and Wright’s focus on major commis- PHOTO COURTESY OF DAVID F. STAFFORD F. OF DAVID COURTESY PHOTO The Luis and Ethel Marden House (completed in 1959) in McLean, Virginia. sions such as the Guggenheim Museum, construction on the Marden House began in 1956. Wright tasked early 50 years after its completion in 1959, the Bob Beharka with on-site supervision of the Marden Luis and Ethel Marden House, spectacularly project and of the Robert Llewellyn Wright house, N situated on a wooded promontory above the a similar almond-shaped, hemicyclical design being roaring Little Falls of the Potomac River built for Wright’s son in nearby Bethesda, Maryland. in McLean, Virginia, stands as one of Frank Lloyd The Marden House was fi nally completed on May Wright’s most stunning Usonian homes and least 30, 1959, at a cost of $76,000. -

Capp to Speak Tomorrow I Truck of the Wmeek ;Ilman Vie for Ulp

|Defic ~xpected .AArrrsa el;ilman Vie For UlP Room, Food Rafes- Steady l -o Two men have declared their intention to run for the office of De sp ie Risig Cosfts' A ' Undergraduate Association Presi- dent. The election will be held RVtXaonDJ1Y Iju1a mLorn4 1--1 n B mO A ae l --1-Lotme Luaung me seonu year Tuesday, March 12. Dormitory room rents and come was expected. to balance exen- The two are Ron Gilman '64, of mons meal fees will remain at ses; and probable deficits in the' ZBT, and Bill Morris '64, of PDT. the present rates next year, said third year were to be offset by Each must get 10 per cent of the Philip A. Stoddard, Vice-Presi- a surplus remaining from a iprof- undergraduate student body to dent, Operations and Personnel. itable fist year. sign a petition before he will offi- Stoddard made the announce- However, no deficits were in- cially be a candidate for the posi- ment after the annual January curred until the -year before last. tion. rviewew of rates. He pointed out Surpluses remaining from 1957-58 Petitions for the UAP nomina- that despite generally rising costs, and 1958 - 59 will finally be ex- tion will be available" from Betty room rentals and commons fees hausted by the end of the current Hendricks in Litchfield Lounge have been held constant for the year. begining Friday, February 15. past five years. Marden explained that next The deadline for retuaning com- Jay L. Marden, Assistant to year's deficit can be offset by a pleted petitions is Friday, March Mr. -

Donald Langmead

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead PRAEGER FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Recent Titles in Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture Paul Gauguin: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Henri Matisse: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Georges Braque: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Willem Marinus Dudok, A Dutch Modernist: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead J.J.P Oud and the International Style: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture, Number 6 Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Langmead, Donald. Frank Lloyd Wright : a bio-bibliography / Donald Langmead. p. cm.—(Bio-bibliographies in art and architecture, ISSN 1055-6826 ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0–313–31993–6 (alk. paper) 1. Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867–1959—Bibliography. I. Title. II. Series. Z8986.3.L36 2003 [NA737.W7] 016.72'092—dc21 2003052890 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Donald Langmead All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003052890 ISBN: 0–313–31993–6 ISSN: 1055–6826 First published in 2003 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the -

Microphone 34 05 12.Pdf

Complete Radio Programs By The Hoúr, A Page To A Day Long Wave J Short Wave ADIO Cents \en-s Spots _ % the Copy ít Piet res NtCW Volume I I I. \: I:I:K BEGINNING MAY 12, 1934 Publi,hcd Weekly This and That Radio Infinite Help To Religion And By Morris Hastings IT IS surprising that not more Education, Says Catholic Educator book -reviewing is done on the radio. Publishers have been exceptional ly slow to take advantage of a na Radio Conference Educator Fr. Ahern ilium which is almost unrivalled for advertising, so those who have made "Radio's Power Is use of radio for Sees t At Madrid Makes School that purpose ac- rar -Reaching" knowledge. of the Air In New York Television Treaty City ALEXAN- DER WOOLL- Radio is one of the best means (:OTT occasion- for helping a large number of peo- ally made ref- ple religiously and, though it will erence to a book 75 Colonies Congress In not take the place of the classroom, during his series radio is a distinct aid in adult edu- of CBS broad- and Nations A Memorial cation. I casts. In Boston, This is the opinion of the Rev. I know of only MICHAEL J. AHERN, S. J., A. M. two "book- talk" Signatories Air Program who for the past three years has programs, that conducted the Catholic Truth Hour A special joint session of Con- given over over the Yankee Network at the MR. HASTINGS Television is of sufficient import- gress, convened in the House Cham- WEE! by Dr. -

Technology of Photography

Technology of Photography Claudia Jacques de Moraes Cardoso Based on Alex Sirota http://iosart.com/photography-art-or-science Camera Obscura Camera Obscura, Georg Friedrich Brander (1713 - 1785), 1769 Light Sensitive Materials • After the camera obscura had been invented and it’s use widely popularized, many dreamt of capturing the images obtained by the camera obscura permanently. • For hundreds of years before photography was invented, people had been aware that some colors are bleached in the sun, but they had made little distinction between heat, air and light. • In 1727, Johann Heinrich Schulze (1687-1744), a German scientist found that silver salts darkened when exposed to sunlight and published results that distinguished between the action of light and heat upon silver salts. • Even after this discovery, a method was needed to halt the chemical reaction so the image wouldn’t darken completely. A Simplified Schematic Representation of the Silver Halide Process First Permanent Picture Joseph Nicephore Niepce (1765-1833), a French inventor, was experimenting with camera obscura and silver chloride. • In 1826, he turned to bitumen of Judea, a kind of asphalt that hardened when exposed to light. • Niepce dissolved the bitumen in lavender oil and coated a sheet of pewter with the mixture. • He placed the sheet in the camera and exposed it for eight hours aimed through an open window at his courtyard. • The light forming the image on the plate hardened the bitumen in bright areas and left it soft and soluble in the dark areas. • Niepce then washed the plate with lavender oil, which removed the still-soft bitumen that hadn’t been struck by light, leaving a permanent image. -

Paul Dummett John Hughes Helen Stephenson

6 Paul Dummett John Hughes Helen Stephenson 57085_00_FM_p001-003_ptg01.indd 1 8/18/14 11:56 AM Life Level 6 Workbook © 2015 National Geographic Learning, a part of Cengage Learning Paul Dummett ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright John Hughes herein may be reproduced, transmitted, stored or used in any form or by Helen Stephenson any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including but not limited to photocopying, recording, scanning, digitizing, taping, Web distribution, Publisher: Sherrise Roehr information networks, or information storage and retrieval systems, Executive Editor: Sarah T. Kenney except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Editorial Assistant: Patricia Giunta Copyright Act, or applicable copyright law of another jurisdiction, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Director of Global Marketing: Ian Martin Senior Product Marketing Manager: For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests Caitlin Thomas online at cengage.com/permissions Director of Content and Media Production: Further permissions questions can be emailed to Michael Burggren [email protected]. Production Manager: Daisy Sosa Workbook Senior Print Buyer: Mary Beth Hennebury ISBN-13: 978-1-305-25708-5 Cover Designer: Scott Baker Cover Image: Michael Melford/National National Geographic Learning/Cengage Learning Geographic Creative 20 Channel Center Street Compositor: MPS Limited Boston, MA 02210 USA Image credit: Cheoh Wee Keat / Getty Images Cengage Learning is a leading provider of customized learning solutions with office locations around the globe, including Singapore, the United Kingdom, Australia, Mexico, Brazil, and Japan. Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Cover Image Education Ltd. -

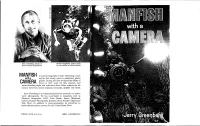

Manfish Camera

Jerry Greenberg relaxes at Photos completed, author heads home between assignments. for the surface to reload camera. MANFISH is a photo-biography of Jerry Greenberg, cover with a ing his first twenty years in underwater photo graphy. During this time he filmed the efforts of CAMERA divers in their quest for fish, treasure, and record-breaking depth and endurance dives. Other subjects for his camera have been marine tropicals, barracuda, dolphin and shark. Jerry Greenberg is an internationally known authority on under water photography. He has contributed to magazines such as National Geographic, LIFE, Paris Match, Sports Illustrated, Camera, Popular Photography, Realities, Stern, Reader's Digest and Skin Diver. In addition to photo-journalism, he specializes in hydro-dynamic photo surveys for the United States Navy. PRICE $2.00 in U.S.A. ISBN: 0-913008-05-2 Contents Foreword. ......................... .. 2 Beachcombing with a camera. ........ .. 3 Spearfishing with the dead-end kids. ... .. 5 Underwater photography. ............ .. 9 Deep dive to death. ................. .. 13 Copyright, 1971 Jerry Greenberg Feeding the pulps. .................. .. 15 ISBN: 0-913008-05-2 24 hours beneath the sea. ............ .. 17 Text by Idaz and Jerry Greenberg. Photographs in this book Cave diving. ........................ .. 21 were taken by Jerry Greenberg unless otherwise indicated. Diamond river caper. ................ .. 25 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publishers, except Roaming the reefs. .................. .. 27 by a reviewer who wishes to quote briefpassages for inclusion Park in the sea. ..................... .. 29 in a magazine or newspaper review. Sealab 1... ......................... .. 33 Some of my best friends are sharks. ... .. 37 Published by 7 sons of supercase. -

Idstorical Diver

Historical Diver, Number 13, 1997 Item Type monograph Publisher Historical Diving Society U.S.A. Download date 04/10/2021 09:15:30 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/30856 IDSTORICAL DIVER Number 13 Fall 1997 Jacques Yves Cousteau Commemorative Issue The Pioneering Years "Allons Voir" HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY USA HISTORICAL DIVER MAGAZINE A PUBLIC BENEFIT NONPROFIT CORPORATION ISSN 1094-4516 2022 CLIFF DRIVE #119 THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA 93109 U.S.A. THE HISTORICAL DIVING SOCIETY U.S.A. PHONE: 805-692-0072 FAX: 805-692-0042 DIVING HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF e-mail: [email protected] or HTTP://WWW.hds.org/ AUSTRALIA, S.E. ASIA ADVISORY BOARD EDITORS Dr. Sylvia Earle Dick Long Leslie Leaney, Editor Dick Bonin J. Thomas Millington, M.D. Andy Lentz, Production Editor CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Scott Carpenter Bob & Bill Meistrell Bonnie Cardone E.R. Cross Nick !corn Jean-Michel Cousteau Bev Morgan Peter Jackson Nyle Monday Jeff Dennis E.R. Cross Phil Nuytten John Kane Jim Boyd Dr. Sam Miller Andre Galeme Sir John Rawlins OVERSEAS EDITORS Lad Handelman Andreas B. Rechnitzer Ph.D. Michael Jung (Germany) Prof. Hans and Lotte Hass Sidney J. Smith Nick Baker (United Kingdom) Les Ashton Smith Jeff Maynard (Australia) Email: [email protected] HISTORICAL DIVER (ISSN 1094-4516) is published four times a SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS year by the Historical Diving Society USA, a Non-Profit Corpora Chairman: Captain Paul Linaweaver M.D., U.S.N. Rtd., Sec tion, 2022 Cliff Drive #119 Santa Barbara, California 93109 USA. retaryffreasurer: James Forte, Directors: Bonnie Cardone, Skip Copyright © 1997 all rights reserved Historical Diving Society USA Dunham, Bob Kirby, Nick Icom, Bob Christiansen, Steve Tel. -

Kalafatas.Pdf

The Bellstone b THE BELLSTONE The Greek Sponge Divers of the Aegean One American’s Journey Home b MICHAEL N. KALAFATAS Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London brandeis university press Published by University Press of New England, 37 Lafayette St., Lebanon, NH 03766 ᭧ 2003 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 Includes the epic poem “Winter Dream” by Metrophanes I. Kalafatas written in 1903 and published in Greek by Anchor Press, Boston, 1919. The poem appears in full both in its English rendering by the poet Olga Broumas, published here for the first time, and in the original Greek, in chapters 11 and 12. “Harlem (2)” on page 161. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated. From THE COLLECTED POEMS OF LANGSTON HUGHES by Langston Hughes, copyright ᭧ 1994 by The Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. Title page illustration: Courtesy Demetra Bowers, from a holograph copy of the poem by Metrophanes Kalafatas. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kalafatas, Michael N. The bellstone : the Greek sponge divers of the Aegean / Michael N. Kalafatas. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1–58465–272–1 1. Sponge divers—Greece—Dodekanesos—History. 2. Sponge fisheries—Greece—Dodekanesos—History. 3. Sponge divers—Greece—Dodekanesos—Poetry. I. Title. HD8039.S55552 G763 2003 331.7'6397—dc21 2002153371 For Joan, for the children, and for those so loved now gone b And don’t forget All through the night The dead are also helping —Yannis Ritsos, from “18 Thin Little Songs of the Bitter Homeland” The poem is like an old jewel buried in the sand. -

Photography-Art-Or-Science.Pdf

Photography - a new art or yet another scientific achievement By Alex Sirota http://iosart.com/photography-art-or-science Contents • Part I - History of Photography • Camera Obscura • Reflex Mirror • Optical Glass and Lenses • Part II - Technology of Photography • Light Sensitive Materials • Daguerreotypes • Roll Film • Color • Digital Photography • Part III - Photography as Art • Pictorialism and Impressionism • Naturalism • Straight Photography • New Vision of the 20th Century • Part IV - Photographic Techniques • Stereoscopic Photography • Infrared Photography • Panoramic Photography • Astrophotography • Pinhole Photography Part I History of Photography Photography The word “photography” which is derived from the Greek words for “light” and “writing”, was first used by Sir John Herschel in 1839, the year the invention of the photographic process was made public. L.J.M Daguerre, "The Louvre from the Left Bank of the Seine” daguerreotype,1839 Scientific Discoveries • The basics of optics - Camera Obscura • Optical glass • Chemical developments - light sensitive materials • Digital Photography Leonardo Da Vinci, The Magic Lantern, 1515 Camera Obscura Camera obscura - Latin, camera - chamber, obscura - dark A dark box or room with a hole in one end. If the hole is small enough, an inverted image can be seen on the opposite wall. Reflex Camera Obscura, Johannes Zahn, 1685 Camera Obscura - Ancient Times • China, Mo Ti (470-391 B.C.) • Greece, Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) • • Egypt, Alhazen (965-1039 A.D.) Chinese texts • The basic optical principles of the pinhole are commented on in Chinese texts from the 5th century B.C. • Chinese writers had discovered by experiments that light travels in straight lines. • The philosopher Mo Ti (470-391 B.C.) was the first to record the formation of an inverted image with a pinhole or screen.