Fine Point Films Belfast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA

Newspaper Licensing Agency - NLA Publisher/RRO Title Title code Ad Sales Newquay Voice NV Ad Sales St Austell Voice SAV Ad Sales www.newquayvoice.co.uk WEBNV Ad Sales www.staustellvoice.co.uk WEBSAV Advanced Media Solutions WWW.OILPRICE.COM WEBADMSOILP AJ Bell Media Limited www.sharesmagazine.co.uk WEBAJBSHAR Alliance News Alliance News Corporate ALLNANC Alpha Newspapers Antrim Guardian AG Alpha Newspapers Ballycastle Chronicle BCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymoney Chronicle BLCH Alpha Newspapers Ballymena Guardian BLGU Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Chronicle CCH Alpha Newspapers Coleraine Northern Constitution CNC Alpha Newspapers Countydown Outlook CO Alpha Newspapers Limavady Chronicle LIC Alpha Newspapers Limavady Northern Constitution LNC Alpha Newspapers Magherafelt Northern Constitution MNC Alpha Newspapers Newry Democrat ND Alpha Newspapers Strabane Weekly News SWN Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Constitution TYC Alpha Newspapers Tyrone Courier TYCO Alpha Newspapers Ulster Gazette ULG Alpha Newspapers www.antrimguardian.co.uk WEBAG Alpha Newspapers ballycastle.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBCH Alpha Newspapers ballymoney.thechronicle.uk.com WEBBLCH Alpha Newspapers www.ballymenaguardian.co.uk WEBBLGU Alpha Newspapers coleraine.thechronicle.uk.com WEBCCHR Alpha Newspapers coleraine.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBCNC Alpha Newspapers limavady.thechronicle.uk.com WEBLIC Alpha Newspapers limavady.northernconstitution.co.uk WEBLNC Alpha Newspapers www.newrydemocrat.com WEBND Alpha Newspapers www.outlooknews.co.uk WEBON Alpha Newspapers www.strabaneweekly.co.uk -

Working Doc 2013 TATT Annual Report.Docx

Key Highlights in 2013: ● V. Ravichandran, India: 2013 recipient of Kleckner Trade & Technology Advancement Award. ● The TATT Global Farmer Network has grown to 106 farmers representing 66 countries. Each member has participated in the TATT Global Farmer Roundtable, held annually in conjunction with the World Food Prize. ● Social Media Leads - Steven Brockshus and Olive Martin – led efforts that have doubled followings on TATT Facebook, Twitter and e-mail distribution. ● TATT Global Farmer Network members authored editorials including prominent placements in USA Today, Wall Street Journal, Nairobi’s Daily Nation, Honolulu Star-Advertiser and others; were interviewed by Associated Press, Bloomberg, Reuters and others; and filled numerous global speaking engagements including the World Food Prize Borlaug Dialogue. Coming in 2014: ● Enhanced utilization of Global Farmer Network voices in support of global trade opportunities, including TPP, T-TIP and WTO conclusion. ● Continued expansion of the Global Farmer Roundtable program with the addition of an international alumni event. ● Nomination of a Global Farmer Network member for the World Food Prize in recognition of Dr. Borlaug’s Centennial Year and his mission to “take it to the farmer”. ● Continued growth in consumer engagement through an enhanced TATT presence on social media platforms. Website Activity 2013: viewers from 176 countries and over 9000 cities across the globe Media Activity – samples that utilized TATT or contain items of interest on Global Farmer Network members: The Advocate (Tasmania) - “Broad outlook seen as farmers’ future” Dec 5 on Craige Mackenzie (GFN, New Zealand). Africa Review - “A forward-looking Kenya can lead the movement for global food sufficiency” May 2 by Gilbert Arap Bor (2011 Kleckner Award, Kenya). -

Worth 1000 Words Illustrated Reportage Makes a Comeback Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | OCTOBER-NOVEMBER 2019 Worth 1000 words Illustrated reportage makes a comeback Contents Main feature 16 Drawing the news The re-emergence of illustrated news News t’s an incredible time to be a journalist if 03 Recognition win at Vice UK you’re involved in Brexit coverage in any way. The extraordinary has become the Agreement after 3-year campaign norm and every day massive stories and 04 Barriers to women photographers twists and turns are guaranteed. Conference shares best practice IIn this edition of The Journalist, Raymond Snoddy celebrates this boom time for journalists 05 UN told of BBC persian plight and journalism in his column. And in an extract from his latest Threats to journalists’ families book, Denis MacShane looks at the role of the press in Brexit. 06 TUC news Extraordinary times also provide the perfect conditions for What the NUJ had to say and more cartoons and satirical illustration. In our cover feature Rachel Broady looks at the re-emergence of illustrated reportage, a “form of journalism that came to prominence in Victorian Features times – and arguably before that with the social commentary of 10 Payment changed my life Hogarth. The work of charity NUJ Extra A picture can indeed be worth 1,000 words. But some writers can also paint wonderfully evocative pictures with their deft 12 Fleet Street pioneers use of words. And on that note, it’s a pleasure to have Paul Women in the top jobs Routledge back in the magazine with a piece on his battle to 14 Database miners free his email address from a voracious PR database. -

Fracking in Ireland Has Grown More More Grown Has Ireland in Fracking Surrounding Debate the To

A thesis submitted to the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy of Central European University in part fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science Should We Risk Fracking the Emerald Isle? The Framing of Fracking Risks in Irish News Media Ariel Sara DREHOBL May 2014 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary Should We Risk Fracking the Emerald Isle? Erasmus Mundus Masters Course in Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management MESPOM This thesis is submitted in fulfillment of the Master of Science degree awarded as a result of successful completion of the Erasmus Mundus Masters course in Environmental Sciences, Policy and Management (MESPOM) jointly operated by the University of the Aegean (Greece), Central European University (Hungary), Lund University (Sweden) and the University of Manchester (United Kingdom). Supported by the European Commission’s Erasmus Mundus Programme CEU eTD Collection ii Ariel Drehobl, Central European University Notes on copyright and the ownership of intellectual property rights: (1) Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the Author. (2) The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Central European University, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. -

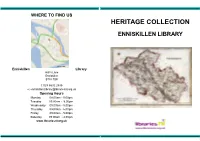

Heritage Collection

WHERE TO FIND US HERITAGE COLLECTION ENNISKILLEN LIBRARY Google maps Enniskillen Library Hall’s Lane Enniskillen BT74 7DR t: 028 6632 2886 e: [email protected] Opening Hours Monday 09.00am - 5.00pm Tuesday 09.00am - 8.00pm Wednesday 09.00am - 5.00pm Thursday 09:00am - 5.00pm Friday 09:00am - 5.00pm Saturday 09:00am - 4.00pm www.librariesni.org.uk ENNISKILLEN HERITAGE holds a large collection of non-fiction and Postcards reference books relating to Irish cultural history and heritage. A major Small collection relating to County Fermanagh and all of Ireland. part of the collection includes locally published works, written by local authors and relating to Co. Fermanagh. Directories Pigot’s, Lowe’s and Slater’s for late 19th century Fermanagh. There is also Journals/Periodicals a collection of Belfast and Ulster Street Directories ranging from 1955 to A significant number of historic and current County Fermanagh journals 1987. and a range of Irish titles are available for consultation - Clogher Record, The Spark, Irish Historical Studies and The Ulster Journal of Special Collections Archaeology just to name a few. Within the main Heritage Collection there are some smaller specialist col- lections reflecting different aspects of life in Ireland including Military Histo- Newspapers ry, W. B. Yeats, Railway History, Genealogy and Heraldry. The Dundas The newspaper collection consists of local County Fermanagh Collection contains material relating to the history of the Dundas family in newspapers - the earliest dating from 1825 up to the present day. The Ireland and Scotland. The Joan Trimble Collection contains material from newspapers are available on microfilm and in hard copy. -

UK & Foreign Newspapers

25th January 2016 UK & Foreign Newspapers UK National Newspapers Please Note Titles marked (ND) are not available for digital copying other than via direct publisher licence. This is the complete list of titles represented by NLA. Your organisation is responsible for advising NLA, or its representative, of the titles you wish to elect and include in your licence cover. The NLA licence automatically includes cover for all UK National Newspapers and five Regional Newspapers. Thereafter you select additional Specialist, Regional and Foreign titles from those listed. Print titles Daily Mail Independent on Sunday The Financial Times (ND) Daily Mirror Observer The Guardian Daily Star Sunday Express The Mail on Sunday Daily Star Sunday Sunday Mirror The New Day Evening Standard Sunday People The Sun i The Daily Express The Sunday Telegraph Independent The Daily Telegraph The Sunday Times The Times Websites blogs.telegraph.co.uk www.guardian.co.uk www.thescottishsun.co.uk fabulousmag.thesun.co.uk www.independent.co.uk www.thesun.co.uk observer.guardian.co.uk www.mailonsunday.co.uk www.thesun.ie www.dailymail.co.uk www.mirror.co.uk www.thesundaytimes.co.uk www.dailystar.co.uk www.standard.co.uk www.thetimes.co.uk www.express.co.uk www.telegraph.co. -

UK & Foreign Newspapers

2nd March 2015 UK & Foreign Newspapers UK National Newspapers Please note that titles marked (ND) are not available for digital copying other than via direct publisher licence. Print titles Daily Mail Independent on Sunday The Financial Times (ND) Daily Mirror Observer The Guardian Daily Star Sunday Express The Mail on Sunday Daily Star Sunday Sunday Mirror The Sun Evening Standard Sunday People The Sunday Telegraph i The Daily Express The Sunday Times Independent The Daily Telegraph The Times Websites blogs.telegraph.co.uk www.guardian.co.uk www.thescottishsun.co.uk fabulousmag.thesun.co.uk www.independent.co.uk www.thesun.co.uk observer.guardian.co.uk www.mailonsunday.co.uk www.thesun.ie www.dailymail.co.uk www.mirror.co.uk www.thesundaytimes.co.uk www.dailystar.co.uk www.standard.co.uk www.thetimes.co.uk www.express.co.uk www.telegraph.co. -

Newsquest Media Group Limited

. IPSO Annual Statement 2016 Newsquest Media Group This is the annual statement of Newsquest Media Group to the Independent Press Standards Organisation for the year 2016. It is made pursuant to clause 3.3.7 and Annex A of the Scheme Membership Agreement and the numbered references below are references to the numbered paragraphs of Annex A. 1. Factual information about the Regulated Entity 1.1 List of titles Appendix 1 to this statement contains a list of Newsquest titles across the UK. 1.2 Responsible Person The Responsible Person (as defined in clause 3.3.9 of the Scheme Membership Agreement) is Simon Westrop, the Group Head of Legal and Company Secretary for Newsquest Media Group Limited. 1.3 The nature of the Regulated Entity Newsquest Media Group is a significant UK publisher in print and online of regional newspapers and magazines, employing approximately 3,500 staff. The Group consists of more than 165 news brands and some 40 magazines across the geographical length of the UK, from Glasgow in Scotland and Brighton and Falmouth in the South of England. The Group consists of mostly weekly newspapers, but there are 19 regional daily titles, among them The Herald in Glasgow, The Northern Echo in Darlington, the Oxford Mail and the Daily Echo in Southampton. The Group’s titles reflect the entire history of the free press in the UK. They start with Berrow’s Worcester Journal, which is believed to be the oldest surviving newspaper in the world. It was first published in 1690, just as the Crown was giving up government licensing of newspapers. -

Annual Report 2020 About Gannett

Annual Report 2020 About Gannett Gannett is a subscription-led and digitally focused media and marketing solutions company committed to empowering communities to thrive. We aim to be the premiere source for clarity, connections, and solutions within our communities. The broad reach of our newsroom network links leading national journalism at USA TODAY, our local property network in 46 states in the U.S., and Newsquest in the U.K. with more than 120 local media brands. This gives us the ability to deepen our relationships with consumers at both the national and local levels. We bring consumers local news and information that impacts their day-to-day lives while keeping them informed of the national events that impact their country. Our USA TODAY NETWORK newsrooms have won 96 Pulitzer Prizes. Gannett also owns the digital marketing services companies ReachLocal, UpCurve and WordStream, which are marketed under the LOCALiQ brand. We have strong relationships with thousands of local and national businesses in both our U.S. and U.K. markets due to our large local and national sales forces and a robust advertising and digital marketing solutions product suite. USA TODAY NETWORK Ventures, our events and promotions business, is the largest media-owned events business in the U.S. The foundation of our business is the employees who make our day-to-day operations possible. We invest in our employees by providing resources and programs to empower personal and professional advancement. Inclusion, Diversity and Equity are core pillars of our organization and influence all that we do. Letter to Shareholders Dear Shareholders: As I wrote my letter to you last year, the COVID-19 While many of the pandemic’s impacts were outside pandemic had just turned our lives upside down of our control, we executed strongly against our and brought on a deep economic slowdown felt stated top priorities and ended 2020 with a stronger globally. -

Out with the Old Boys Media Networking for the Many, Not the Few Contents

MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL UNION OF JOURNALISTS WWW.NUJ.ORG.UK | DECEMBER-JANUARY 2020 Out with the old boys Media networking for the many, not the few Contents Main feature 16 Beating the old boy network How to break the ‘class ceiling’ News elcome to the last edition of 2019. 03 Scottish titles in strike vote It’s that time of the year when we look back and make plans and Anger at fresh Newsquest cuts changes for the new year. 04 ‘Scroogequest’ cuts hit local papers In a similar spirit of changing NUJ urges new investment Wsomething old for something new, our cover feature looks at how the old boys’ club is being 05 Dutch court boosts freelance pay changed in the media for a new way of networking. Holly Judgement hailed as historic Powell-Jones looks at how mentoring and helping young people 06 Irish delegate conference find accommodation in expensive cities can promote diversity Reports on biennial meeting in the media and give newcomers that all important first step. Another recent change in the media landscape is the growing “opportunity for journalists to make money from newsletters. Features Jem Collins guides us through the ins and outs of the subject. 10 Getting close to readers We’ve got a bit of looking back too. Jonathan Sale continues Newsletters can boost income his absorbing and entertaining media anniversary series, this time throwing the spotlight on the first newspaper colour 12 A riot of colour supplement. And Phil Chamberlain takes a look at the heyday Uproar over first supplements of the radical press and a new project to document it. -

BMJ in the News Is a Weekly Digest of Journal Stories, Plus Any Other News

BMJ in the News is a weekly digest of journal stories, plus any other news about the company that has appeared in the national and a selection of English-speaking international media. A total of 28 journals were picked up in the media last week (2-8 November) - our highlights include: ● Research in The BMJ suggesting that delaying cancer treatment by even one month can raise the risk of death by around 10% made global headlines, including The Guardian, International Business Times, and The South China Morning Post. ● An opinion piece published in the Journal of Medical Ethics arguing that governments should pay people to get a COVID-19 jab, when the vaccine becomes available, to ensure widespread coverage was picked up internationally, including Sky News, Hindu Business Line and the New York Post. ● An analysis in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry finding that Asian ethnicity is strongly linked to COVID-related stroke made headlines in Scienmag, The Times, and Medical Republic. BMJ PRESS RELEASES The BMJ | Journal of Medical Ethics Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry EXTERNAL PRESS RELEASES Archives of Disease in Childhood | BMJ Global Health BMJ Open | Emergency Medicine Journal Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry OTHER COVERAGE The BMJ | Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases BMJ Case Reports | BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health | BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care BMJ Open Ophthalmology | BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine -

Independent. Accessible. Bold. Transparent. Fair

Independent. Accessible. Transparent. Bold. Fair. Annual Report 2018 CONTENTS IPSO Annual Report 2018 Regulation is vital for 3 The Chairman protecting the public.” 4 The Chief Executive 5 Values Rt. Hon. Sir Alan Moses 6 Information to support the public CHAIRMAN 8 Response to the Kerslake Review ive years ago, few would have believed The personalities may have changed but the qualities that we would make such determined have not. They all set examples of independence of 10 Quality guidance and training progress in establishing regulation as vital thought and decision, examples which have been for protecting the public and maintaining whole-heartedly followed. As the renewal of five year 12 Transparent monitoring and scrutiny freedom of expression. But I am confident contracts between IPSO and its regulated entities that IPSO is now justified in making that has just taken place, it is worth re-iterating that the 14 The IPSO mark and fake news Fclaim. Standing at the boundary between protection public will be best protected by voluntary but binding of freedom of expression and the harm that may be agreements by which the press submit to regulation 15 Compulsory arbitration caused by unregulated opinion and news, we cannot by IPSO. The past five years shows, beyond question, escape criticism from both the public and those we the importance of this as a framework for a free and 16 Complaints regulate. But that criticism merely shows how seriously vibrant press and protection for the public. they take our rulings and guidance. 18 Most complained about articles If this has a touch of retrospective pride and optimism Our achievements are due, in the main, to four for the future, I hope I may be forgiven because, a 19 Case studies features of IPSO: our administrators who daily new Chair has been selected and I will leave at the engage with the public with patient concern; our end of 2019.