Complications Following Central Corpectomy in 468 Consecutive Patients with Degenerative Cervical Spine Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anterior Reconstruction Techniques for Cervical Spine Deformity

Neurospine 2020;17(3):534-542. Neurospine https://doi.org/10.14245/ns.2040380.190 pISSN 2586-6583 eISSN 2586-6591 Review Article Anterior Reconstruction Techniques Corresponding Author for Cervical Spine Deformity Samuel K. Cho 1,2 1 1 1 https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7511-2486 Murray Echt , Christopher Mikhail , Steven J. Girdler , Samuel K. Cho 1Department of Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA Department of Orthopaedics, Icahn 2 Department of Neurological Surgery, Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 425 NY, USA West 59th Street, 5th Floor, New York, NY, USA E-mail: [email protected] Cervical spine deformity is an uncommon yet severely debilitating condition marked by its heterogeneity. Anterior reconstruction techniques represent a familiar approach with a range Received: June 24, 2020 of invasiveness and correction potential—including global or focal realignment in the sagit- Revised: August 5, 2020 tal and coronal planes. Meticulous preoperative planning is required to improve or prevent Accepted: August 17, 2020 neurologic deterioration and obtain satisfactory global spinal harmony. The ability to per- form anterior only reconstruction requires mobility of the opposite column to achieve cor- rection, unless a combined approach is planned. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion has limited focal correction, but when applied over multiple levels there is a cumulative ef- fect with a correction of approximately 6° per level. Partial or complete corpectomy has the ability to correct sagittal deformity as well as decompress the spinal canal when there is an- terior compression behind the vertebral body. -

2019 Spine Coding Basics

2019 Spine Coding Basics Presenter: Kerri Larson, CPC Directory of Coding and Audit Services 2019 Spine Surgery 01 Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy 02 Spine Procedures 03 Case Study 04 Diagnosis 05 Q & A Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Term Definition Arthrodesis Fusion, or permanent joining, of a joint, or point of union of two musculoskeletal structures, such as two bones Surgical procedure that replaces missing bone with material from the patient's own body, or from an artificial, synthetic, or Bone grafting natural substitute Corpectomy Surgical excision of the main body of a vertebra, one of the interlocking bones of the back. Cerebrospinal The protective body fluid present in the dura, the membrane covering the brain and spinal cord fluid or CSF Decompression A procedure to remove pressure on a structure. Diskectomy, Surgical removal of all or a part of an intervertebral disc. discectomy Dura Outermost of the three layers that surround the brain and spinal cord. Electrode array Device that contains multiple plates or electrodes. Electronic pulse A device that produces low voltage electrical pulses, with a regular or intermittent waveform, that creates a mild tingling or generator or massaging sensation that stimulates the nerve pathways neurostimulator Spine Surgery Terminology & Anatomy Term Definition The space that surrounds the dura, which is the outermost layer of membrane that surrounds the spinal canal. The epidural space houses the Epidural space spinal nerve roots, blood and lymphatic vessels, and fatty tissues . Present inside the skull but outside the dura mater, which is the thick, outermost membrane covering the brain or within the spine but outside Extradural the dural sac enclosing the spinal cord, nerve roots and spinal fluid. -

Two-Level Cervical Corpectomy—Long-Term Follow-Up Reveals the High Rate of Material Failure in Patients, Who Received an Anterior Approach Only

Neurosurgical Review (2019) 42:511–518 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-018-0993-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Two-level cervical corpectomy—long-term follow-up reveals the high rate of material failure in patients, who received an anterior approach only Simon Heinrich Bayerl1 & Florian Pöhlmann1 & Tobias Finger1 & Vincent Prinz1 & Peter Vajkoczy 1 Received: 25 August 2017 /Revised: 20 November 2017 /Accepted: 5 December 2017 /Published online: 18 June 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract In contrast to a one-level cervical corpectomy, a multilevel corpectomy without posterior fusion is accompanied by a high material failure rate. So far, the adequate surgical technique for patients, who receive a two-level corpectomy, remains to be elucidated. The aim of this study was to determine the long-term clinical outcome of patients with cervical myelopathy, who underwent a two-level corpectomy. Outcome parameters of 21 patients, who received a two-level cervical corpectomy, were retrospectively analyzed concerning reoperations and outcome scores (VAS, Neck Disability Index (NDI), Nurick scale, mod- ified Japanese Orthopaedic Association score (mJOAS), Short Form 36-item Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36)). The failure rate was determined using postoperative radiographs. The choice over the surgical procedures was exercised by every surgeon individually. Therefore, a distinction between two groups was possible: (1) anterior group (ANT group) with a two-level corpectomy and a cervical plate, (2) anterior/posterior group (A/P group) with two-level corpectomy, cervical plate, and addi- tional posterior fusion. Both groups benefitted from surgery concerning pain, disability, and myelopathy. While all patients of the A/P group showed no postoperative instability, one third of the patients of the ANT group exhibited instability and clinical deterioration. -

The Need for Structural Allograft Biomechanical Guidelines

8 The Need for Structural Allograft Biomechanical Guidelines Satoshi Kawaguchi, MD Robert A. Hart, MD Abstract Because of their osteoconductive properties, structural bone allografts retain a theoretic advantage in biologic performance compared with artifi cial interbody fusion devices and endoprostheses. Current regulations have addressed the risks of disease transmission and tissue contamination, but comparatively few guidelines exist regarding donor eligibility and bone processing issues with a potential effect on the mechanical integrity of structural allograft bone. The lack of guidelines appears to have led to variation among allograft providers in terms of processing and donor screening regarding issues with recognized mechanical effects. Given the relative lack of data on which to base reasonable screening standards, a basic biomechanical evaluation was performed on one source of structural bone allograft, the femoral ring. Of the tested parameters, the minimum and maximum cortical wall thicknesses of femoral ring allograft were most strongly correlated with the axial compressive load to failure of the graft, suggesting that cortical wall thickness may be a useful screening tool for compressive resistance expected from fresh cortical bone allograft. Development of further biomechanical and clinical data to direct standard development appears warranted. Instr Course Lect 2015;64:87–93. Surgical implantation of structural al- form with limited anatomic modifi - by the US FDA as well as through vol- lograft bone continues to increase de- cations, modern tissue processing in- untary participation with the American spite advances in modern alternatives cludes preparations of amalgams of Association of Tissue Banks (AATB). to allograft, including spine interbody allograft bone tissue of specifi c shapes Guidelines for allograft bone products fusion devices and peripheral joint en- and sizes to suit specifi c surgical needs. -

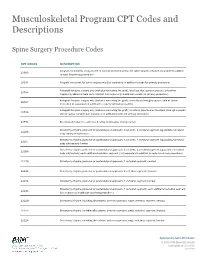

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for -

Differences Between Subtotal Corpectomy and Laminoplasty for Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

Spinal Cord (2010) 48, 214–220 & 2010 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Differences between subtotal corpectomy and laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy S Shibuya1, S Komatsubara1, S Oka2, Y Kanda1, N Arima1 and T Yamamoto1 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Kagawa University, Kagawa, Japan and 2Oka Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation Clinic, Kagawa, Japan Objective: This study aimed to obtain guidelines for choosing between subtotal corpectomy (SC) and laminoplasty (LP) by analysing the surgical outcomes, radiological changes and problems associated with each surgical modality. Study Design: A retrospective analysis of two interventional case series. Setting: Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kagawa University, Japan. Methods: Subjects comprised 34 patients who underwent SC and 49 patients who underwent LP. SC was performed by high-speed drilling to remove vertebral bodies. Autologous strut bone grafting was used. LP was performed as an expansive open-door LP. The level of decompression was from C3 to C7. Clinical evaluations included recovery rate (RR), frequency of C5 root palsy after surgery, re-operation and axial pain. Radiographic assessments included sagittal cervical alignment and bone union. Results: Comparisons between the two groups showed no significant differences in age at surgery, preoperative factors, RR and frequency of C5 palsy. Progression of kyphotic changes, operation time and volumes of blood loss and blood transfusion were significantly greater in the SC (two- or three- level) group. Six patients in the SC group required additional surgery because of pseudoarthrosis, and four patients underwent re-operation because of adjacent level disc degeneration. -

Analysis of a Spine Registry Rate Among Smokers Undergoing

No Difference in Functional Outcome but Higher Revision Rate Among Smokers Undergoing Cervical Artificial Disc Replacement: Analysis of a Spine Registry Lee Wen-Shen, Maksim Lai Wern Sheng, William Yeo, Tan Seang Beng, Yue Wai Mun, Guo Chang Ming and Mohammad Mashfiqul Arafin Siddiqui Int J Spine Surg published online 29 December 2020 http://ijssurgery.com/content/early/2020/12/17/7140 This information is current as of October 2, 2021. Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://ijssurgery.com/alerts The International Journal of Spine Surgery 2397 Waterbury Circle, Suite 1, Aurora, IL 60504, Phone: +1-630-375-1432 © 2020 ISASS. All RightsDownloaded Reserved. from http://ijssurgery.com/ by guest on October 2, 2021 International Journal of Spine Surgery, Vol. 00, No. 00, 0000, pp. 000–000 https://doi.org/10.14444/7140 ÓInternational Society for the Advancement of Spine Surgery No Difference in Functional Outcome but Higher Revision Rate Among Smokers Undergoing Cervical Artificial Disc Replacement: Analysis of a Spine Registry LEE WEN-SHEN, MBBS (HONS),1,2 MAKSIM LAI WERN SHENG, MBBS,1 WILLIAM YEO,3 TAN SEANG BENG, MBBS, FRCS,1 YUE WAI MUN, MBBS, FRCS,1 GUO CHANG MING, MBBS, FRCS,1 MOHAMMAD MASHFIQUL ARAFIN SIDDIQUI, MBBS, FRCS1 1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore 2Department of Surgery, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, 3Statistics and Clinical Research, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore ABSTRACT Background: Smoking is a known predictor of negative outcomes in spinal surgery. However, its effect on the functional outcomes and revision rates after ADR is not well-documented. -

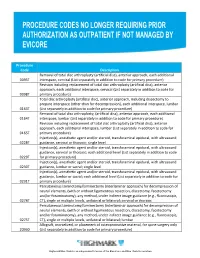

Procedure Codes No Longer Requiring Prior

Procedure Code Description Removal of total disc arthroplasty (artificial disc), anterior approach, each additional 0095T interspace, cervical (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Revision including replacement of total disc arthroplasty (artificial disc), anterior approach, each additional interspace, cervical (List separately in addition to code for 0098T primary procedure) Total disc arthroplasty (artificial disc), anterior approach, including discectomy to prepare interspace (other than for decompression), each additional interspace, lumbar 0163T (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Removal of total disc arthroplasty, (artificial disc), anterior approach, each additional 0164T interspace, lumbar (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Revision including replacement of total disc arthroplasty (artificial disc), anterior approach, each additional interspace, lumbar (List separately in addition to code for 0165T primary procedure) Injection(s), anesthetic agent and/or steroid, transforaminal epidural, with ultrasound 0228T guidance, cervical or thoracic; single level Injection(s), anesthetic agent and/or steroid, transforaminal epidural, with ultrasound guidance, cervical or thoracic; each additional level (List separately in addition to code 0229T for primary procedure) Injection(s), anesthetic agent and/or steroid, transforaminal epidural, with ultrasound 0230T guidance, lumbar or sacral; single level Injection(s), anesthetic agent and/or steroid, transforaminal epidural, -

Priority Health Spine and Joint Code List

Priority Health Joint Services Code List Category CPT® Code CPT® Code Description Joint Services 23000 Removal of subdeltoid calcareous deposits, open Joint Services 23020 Capsular contracture release (eg, Sever type procedure) Joint Services 23120 Claviculectomy; partial Joint Services 23130 Acromioplasty or acromionectomy, partial, with or without coracoacromial ligament release Joint Services 23410 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open; acute Joint Services 23412 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open;chronic Joint Services 23415 Coracoacromial ligament release, with or without acromioplasty Joint Services 23420 Reconstruction of complete shoulder (rotator) cuff avulsion, chronic (includes acromioplasty) Joint Services 23430 Tenodesis of long tendon of biceps Joint Services 23440 Resection or transplantation of long tendon of biceps Joint Services 23450 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior; Putti-Platt procedure or Magnuson type operation Joint Services 23455 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior;with labral repair (eg, Bankart procedure) Joint Services 23460 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior, any type; with bone block Joint Services 23462 Capsulorrhaphy, anterior, any type;with coracoid process transfer Joint Services 23465 Capsulorrhaphy, glenohumeral joint, posterior, with or without bone block Joint Services 23466 Capsulorrhaphy, glenohumeral joint, any type multi-directional instability Joint Services 23470 ARTHROPLASTY, GLENOHUMERAL JOINT; HEMIARTHROPLASTY ARTHROPLASTY, GLENOHUMERAL JOINT; TOTAL SHOULDER [GLENOID -

Musculoskeletal Surgical Procedures Requiring Prior Authorization (Effective 11.1.2020)

Musculoskeletal Surgical Procedures Requiring Prior Authorization (Effective 11.1.2020) Procedure Code Description ACL Repair 27407 Repair, primary, torn ligament and/or capsule, knee; cruciate ACL Repair 27409 Repair, primary, torn ligament and/or capsule, knee; collateral and cruciate ligaments ACL Repair 29888 Arthroscopically aided anterior cruciate ligament repair/augmentation or reconstruction Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 23130 Acromioplasty Or Acromionectomy, Partial, With Or Without Coracoacromial Ligament Release Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 23410 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open; acute Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 23412 Repair of ruptured musculotendinous cuff (eg, rotator cuff) open; chronic Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 23415 Coracoacromial Ligament Release, With Or Without Acromioplasty Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 23420 Reconstruction of complete shoulder (rotator) cuff avulsion, chronic (includes acromioplasty) Arthroscopy, Shoulder, Surgical; Decompression Of Subacromial Space With Partial Acromioplasty, With Coracoacromial Ligament (Ie, Arch) Release, When Performed (List Separately In Addition Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 29826 To Code For Primary Procedure) Acromioplasty and Rotator Cuff Repair 29827 Arthroscopy, shoulder, surgical; with rotator cuff repair Allograft for Spinal Fusion [BMP] 20930 Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only Ankle Fusion 27870 Arthrodesis, ankle, open Ankle Fusion -

Posterior Foraminotomy Versus Anterior Decompression and Fusion

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg Spine 32:344–352, 2020 Posterior foraminotomy versus anterior decompression and fusion in patients with cervical degenerative disc disease with radiculopathy: up to 5 years of outcome from the national Swedish Spine Register Anna MacDowall, MD, PhD,1 Robert F. Heary, MD,2 Marek Holy, MD,3 Lars Lindhagen, PhD,4 and Claes Olerud, MD, PhD1 1Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden; 2Department of Neurological Surgery, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey; 3Department of Orthopedics, Örebro University Hospital, Örebro; and 4Uppsala Clinical Research Center, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden OBJECTIVE The long-term efficacy of posterior foraminotomy compared with anterior cervical decompression and fusion (ACDF) for the treatment of degenerative disc disease with radiculopathy has not been previously investigated in a population-based cohort. METHODS All patients in the national Swedish Spine Register (Swespine) from January 1, 2006, until November 15, 2017, with cervical degenerative disc disease and radiculopathy were assessed. Using propensity score matching, pa- tients treated with posterior foraminotomy were compared with those undergoing ACDF. The primary outcome measure was the Neck Disability Index (NDI), a patient-reported outcome score ranging from 0% to 100%, with higher scores indicating greater disability. A minimal clinically important difference was defined as > 15%. Secondary outcomes were assessed with additional patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). RESULTS A total of 4368 patients (2136/2232 women/men) met the inclusion criteria. Posterior foraminotomy was performed in 647 patients, and 3721 patients underwent ACDF. After meticulous propensity score matching, 570 patients with a mean age of 54 years remained in each group. -

Surgical Anatonly of the Anterior Cervical Spine: the Disc Space, Vertebral Artery, and Associated Bony Structures

Surgical AnatonlY of the Anterior Cervical Spine: The Disc Space, Vertebral Artery, and Associated Bony Structures T. Glenn Pait, M.D., James A. Killefer, M.D., Kenan I. Arnautovic, M.D. Department of Neurosurgery, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas (TGP, KIA), and Department of Neurosurgery (jAK), West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia OBJECTIVE: To elucidate the relationships between the neurovascular structures and surrounding bone, which are hidden from the surgeon by soft tissue, and to aid in avoiding nerve root and vertebral artery injury in anterior cervical spine surgery. METHODS: Using six cadaveric spines, we measured important landmarks on the anterior surface of the spine, the bony housing protecting the neurovascular structures in the lateral disc space, and the changes that occur during the discectomy with interbody distraction of the vertebral bodies. The measurements included the distance between the medial borders of the longus colli muscle at the level of each interspace; the width and height of each disc space at the midline; the width and height of the costal process; the distances between the cranial tip of the uncinate process (UP) and the vertebral body (VB) above and from the tip of the UP to the vertebral artery; the anteroposterior diameter or the extent of the disc spaces in the midline; the height at the midpoint of the distracted disc space; the UP-VB distance in distraction; and the width of the visible nerve root. RESULTS: The distance between the medial borders of the longus colli muscles increased in a rostral to caudal direction. The height of the UP was shortest at C4-C5 and greatest at C5-C6; the width was narrowest at C4-C5 and widest at C6-C7.