Determining a Proper Test for Inherent Distinctiveness in Trade Dress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Company Contact Information

Moola SavingMom.com Company Contact List Company Manufacturer Phone Website Contact Us Email Form Actual Email Address Address 1 Address 2 City/State/Zip 3 Musketeers Dr.Mars, Pepper Inc. Snapple http://www.3musketeers.com/ https://www.3musketeers.com/Contact 7-Up Group 1-800-696-5891 http://www.7up.com/ http://www.econsumeraffairs.com/am_bev/contactus.htm?F1=7up&F2=7up Attn: Consumer Relations P.O. Box 86077 Plano, TX 75086-9077 9Lives Cat Food Big Heart Pet Brands 1-800-252-7022 http://9lives.com/ http://www.bigheartpet.com/Contact/ContactUs.aspx A.1. Sauce Dr.Kraft Pepper Foods Snapple 1-877-535-5666 http://www.kraftrecipes.com/products/a1.aspx http://kraftfoods.custhelp.com/app/contact/sa/1/ Consumer Relations Three Lakes Drive Northfield, IL 60093 A&W Rootbeer Group http://www.rootbeer.com/ http://www.econsumeraffairs.com/am_bev/contactus.htm?F1=rootbeer&F2=A_W Abbott Nutrition (800) 227-5767 http://abbottnutrition.com/ https://abbottnutrition.com/contact-us ACH Food Companies, Inc. 800-247-5251 http://www.achfood.com/ http://www.achfood.com/contact-us.cfm [email protected] 2301 SE Tone’s Drive Ankeny, IA 50021-8888 ACT Chattem, Inc. http://www.actoralcare.com/ http://www.actoralcare.com/contact-us/ Chattem, Inc. P.O. Box 2219 Chattanooga, TN 37409-0219 Advil Colgate-PalmolivePfizer Inc 1-800-882-3845 http://www.advil.com/ http://www.advil.com/faqs PCH Product Information PO Box 1043 Kings Mountain, NC 28086 Ajax Company 1-800-468-6502 http://www.colgate.com/app/PDP/Ajax/US/EN/home.cwsp http://www.colgate.com/app/Colgate/US/Corp/ContactUs.cvsp Aleve Bayer Healthcare LLC 1-800-395-0689 http://www.aleve.com/ http://www.aleve.com/contact/email-us/ Attn: Consumer Relations 100 Bayer Boulevard Whippany, NJ 07981-0915 Alka-Sletzer Bayer Healthcare, LLC 1-800-986-0369 http://www.alkaseltzer.com/as/ http://www.alkaseltzer.com/as/contact.html http://www.alkaseltzer.com/as/emailus.html Attn: Consumer Relations 100 Bayer Boulevard Whippany, NJ 07981-0915 Allegra Chattem, Inc. -

Tri R Coffee & Vending Product List

Tri R Coffee & Vending Product List Cold Beverages Pepsi Snapple Juice Snapple Diet Pepsi Max Snapple Tea Snapple Lemon Pepsi Natural Dasani Water Snapple Pink Lemonade Pepsi One SoBe Energize Mango Melon Lipton Brisk Strawberry Melon Pepsi Throwback SoBe Energize Power Fruit Punch Lipton Brisk Sugar Free Lemonade Caffeine Free Pepsi SoBe Lean Fuji Apple Cranberry Lipton Brisk Sugar Free Orangeade Diet Pepsi SoBe Lean Honey Green Tea Lipton Brisk Sweet Iced Tea Diet Pepsi Lime SoBe Lean Raspberry Lemonade Lipton Diet Green Tea with Citrus Diet Pepsi Vanilla SoBe Lifewater Acai Fruit Punch Lipton Diet Green Tea with Mixed Berry Diet Pepsi Wild Cherry SoBe Lifewater Agave Lemonade Lipton Diet Iced Tea with Lemon Caffeine Free Diet Pepsi SoBe Lifewater B-Energy Black Cherry Dragonfruit Lipton Diet White Tea with Raspberry Sierra Mist Natural SoBe Lifewater B-Energy Strawberry Apricot Lipton Green Tea with Citrus Diet Sierra Mist SoBe Lifewater Black and Blue Berry Lipton Iced Tea Lemonade Sierra Mist Cranberry Splash SoBe Lifewater Blackberry Grape Lipton Iced Tea with Lemon Diet Sierra Mist Cranberry Splash SoBe Lifewater Cherimoya Punch Lipton PureLeaf - Diet Lemon Diet Sierra Mist Ruby Splash SoBe Lifewater Fuji Apple Pear Lipton PureLeaf - Extra Sweet Ocean Spray Apple Juice SoBe Lifewater Macintosh Apple Cherry Lipton PureLeaf - Green Tea with Honey Ocean Spray Blueberry Juice Cocktail SoBe Lifewater Mango Melon Lipton PureLeaf - Lemon Ocean Spray Cranberry Juice Cocktail SoBe Lifewater Orange Tangerine Lipton PureLeaf - Peach Ocean -

The Ultimate A-Z of Dog Names

Page 1 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names To Barney For his infinite patience and perserverence in training me to be a model dog owner! And for introducing me to the joys of being a dog’s best friend. Please do not copy this book Richard Cussons has spent many many hours compiling this book. He alone is the copyright holder. He would very much appreciate it if you do not make this book available to others who have not paid for it. Thanks for your cooperation and understanding. Copywright 2004 by Richard Cussons. All rights reserved worldwide. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of Richard Cussons. Page 2 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names Contents Contents The ultimate A-Z of dog names 4 How to choose the perfect name for your dog 5 All about dog names 7 The top 10 dog names 13 A-Z of 24,920 names for dogs 14 1,084 names for two dogs 131 99 names for three dogs 136 Even more doggie information 137 And finally… 138 Bonus Report – 2,514 dog names by country 139 Page 3 of 155 The ultimate A-Z of dog names The ultimate A-Z of dog names The ultimate A-Z of dog names Of all the domesticated animals around today, dogs are arguably the greatest of companions to man. -

Article Article Description EAN/UPC 293 PET RITZ 482 AMYS 508 J

Article Article Description EAN/UPC 293 PET RITZ 482 AMYS 508 J DEAN TKY SSG EGG CHS MUFFIN 4 CT 00077900502415 511 J DEAN CAN BCN EGG CHEESE MUFFIN 4 CT 00077900502422 512 J DEAN TKY SSG EGG CHSE R F CRSSNT 4 CT 00077900502576 1028 ORE IDA GOLDEN FRIES 32 OZ 00013120002588 1030 ORE IDA TATER TOTS 32 OZ 00013120000829 1039 ORE IDA GOLDEN CRINKLES 32 OZ 00013120002861 1375 SISTER SCHUBERT'S CINN ROLLS 16 OZ 00748162111799 1735 KLONDIKE 2063 STOUFFRS ESY EXP CHSY GRLIC LASGNA 35 OZ 00013800446770 2512 MARY B'S BISCUIT 2690 STF 90 OZ MT LASAGNA 90 OZ 00013800551320 2785 WELCH GRAPE 3454 MC SOUTHERN PECAN PIE 32 OZ 00612781102202 3462 MICH FET ALF BROC & CKN 8.5 OZ 00717854105217 4243 AMYS MARGHERITA PIZZA 13 OZ 00042272001996 4244 AMY'S SPINACH PIZZA 14 OZ 00042272001026 4387 REAMES HOME STYL EGG NDLS 12 OZ 00041308000279 4723 ORE IDA XCRSPY TATER TOTS 28 OZ 00013120012617 4745 LEAN PCKT CHCKN CHDR BROCCOLI 4762 MARY B BISCUIT, BUTTERMILK 00020593000201 5732 TOTINO PIZZA RLS 5767 TOTINO PIZZA RLS 5844 TOTINO 90CT PIZZA 6124 JIMMY DEAN 6348 BE STEAMFRESH 6936 B&J ICE CRM 6995 JIMMY DEAN SSG & GVY BK BOWL 7 OZ 00077900471414 7202 JOSE OLE EG BCN CH BRK BRTO 4 OZ 00073202892933 7209 MM JUICE BARS 7718 STOUFFER PEPP PIZZA 11.25 OZ 00013800151735 8287 GG CORN ON COB 8336 M/CLNDR SPAG W/MT & BRD 13.3 OZ 00021131905354 8339 MCLNDR CHS CKN RICE BOWL 12 OZ 00021131506629 8512 MICHELINA FETT ALFREDO 8.5 OZ 00717854105019 8621 MICH LN GRMT 5CHS LASAGNA 8 OZ 00717854106276 8627 MICH LN GRMT SLSBRY STKMSHPOT 8 OZ 00717854106306 8632 MICH SALISSTK&CVYW/POT -

Island*Hp Hood*Philadelphia Water Ice* Jack&Jill*Breyers*Edy's*Good Humor* * Ice Cream * Frozen Yogurt * Italian Ices * Soft Serve * Frozen Desserts*

(609) 522-0438 *ISLAND*HP HOOD*PHILADELPHIA WATER ICE* JACK&JILL*BREYERS*EDY'S*GOOD HUMOR* * ICE CREAM * FROZEN YOGURT * ITALIAN ICES * SOFT SERVE * FROZEN DESSERTS* NOVELTIES #CASE *NEW* NOVELTIES FOR 2017 SOFT SERVE MIX - Freshlife Good Humor Items - Core in Bold B&J Cookie Dough Slices (2 Doz) 6-1/2 Gallon Cartons/Case (3 Gal.) Big Stick - Red, White & Blue (2 Doz) Other Novelties Ice Cream 10% Vanilla Birthday Cake Bar (2 Doz) Banana Fudge (1 Doz) Ice Cream 10% Chocolate B&J Cups Cherry Garcia/Cookie Do (1 Doz) Chipwich (Jack & Jill ) (2 Doz) 2-2 1/2 Gallon Bags/Case (5 Gal.) Choco Taco (2 Doz) Cookie & Cream Cup (1 Doz) Ice Cream 5% Vanilla Chocolate Éclair Bar (2 Doz) Cotton Candy Swirl Bar (2 Doz) Ice Cream 5% Chocolate Cookie Sandwich (2 Doz) Dibs (1 Doz) WHIPPED CREAM 12-14oz. cans Cyclone Stick-Hyperstripe (2 Doz) Dove Bar (1 Doz) FROZEN YOGURT 4-1 Gal. Giant King Cone-V/C (1 Doz) FrozFruit Bars (2 Doz) Honey Hill Farms Category 1 Giant Oreo Sandwich (2 Doz) Fruit Stix Bars (2 Doz) Honey Hill Farms Category 2 Giant Sandwich (2 Doz) Fudge Bar (Jack & Jill ) (2 Doz) Honey Hill Farms Category 3 Hello Kitty Face Pop (1 Doz) Haagen Daz Ice Cream Bar (1 Doz) * Other Flavors Upon Request King Cone - Vanilla (2 Doz) Shortcake / Éclair (Jack & Jill ) (2 Doz) Klondike Bar (2 Doz) Ice Cream Bars (Jack & Jill ) (2 Doz) FROZEN TOPPINGS 10 lbs. Magnum Double Caramel Bar (1 Doz) Ice Cream Sandwich (Jack & Jill ) (3 Doz) Brownie Bites / Cookie Dough Pieces / Magnum Core Dbl. -

I798 JACKSON Jackson, Phil, 1349 Jackson, Thomas Penfield, Ro3 8

I798 JACKSON INDEX INDEX JORDAN MCGRATH CASE & TAYLOR, INC. I799 798, I2oI, I266, I52I, i601; Thrille~ Japan Advertising Agency Association, 466, Jennings, Peter, 95, 523 Joe Camel, 311, 316, 336, 539, 690, 760, Johnson, Ray, 77 (Durham, North Carolina). See under r520; "Thrille1;" Io92 469, 878 Jenny Craig International. See under Craig 1212, 1369, 1694 Johnson, Robert Wood, Jr., 880, 881, 882 Harttnan Jackson, Phil, 1349 Japan Advertising Council, 468 Jeno's Pizza, 623, 1234, 1235 Joe Chemo, 336 Johnson, Robert Wood, Sr., 880 John W. Shaw Advertising. See under Shaw Jackson, Reggie, 148r, I482 Japan Air Lines, 898, 900, 1462 Jensen, Thomas, 525 Joe Isuzu, 114, II4, 457, 475, 522 Johnson, Samuel, 749 John Wanamaker & Company. See under Jackson, Thomas Penfield, ro3 8 Japan Audit Bureau of Circulation Jenson, Nicolas, 1580, 1583 foe Palooka, 729 Johnson, Samuel Curtis, 884, 886, 888 Wanamaker Jackson & Perkins, 1673 Association, 466 Jenson typefaces, 1580, 1583, 1584 Joe Robbie Stadiun1, 335 Johnson, William H., 139 "Join the Dodge rebellion," 305 Jacksonville Jaguars, 3 3 5 japan Marketing Association, 466 Jeopardy!, 1426. See also color plate in "Jogger," 940 Johnson, William R., 730 "Join the people who've joined the Army," Jackson Wain Agency, 1071 144, 238, I437 Japan Newspaper Advertising Agency volume one John, W.A.P., 791 Mead Johnson & Co1npany, 57, 210, 880 1050 Jack Tinker & Partners. See under Tinker Association, 466 Jep et Carre, 618 "John and Marsha" (Freberg), 623, 824 Johnson & Johnson, 582, 880-83; Ammirati Joint Policy Com1nittee for Broadcast Talent Jacob Ruppert, Inc. See under Ruppert Jardine Matheson & Company, 301 ]e Reviens, 1202 John Birch Society, 1676 Puris Lintas and, 967; Batten Barton Union Relations, 99 Jacobs, Alan, 197 Jarreau, Al, 1395 Andrew Jergens Company: Cunningham & John Brown & Partners. -

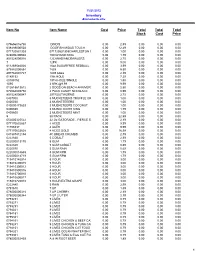

NH Convenient Database

11/21/2012 Inventory Alphabetically Item No Item Name Cost Price Total Total Total Stock Cost Price 075656016798 DINO'S 0.00 2.59 0.00 0.00 0.00 638489000503 DOGFISH MIDAS TOUCH 0.00 12.49 0.00 0.00 0.00 071720531303 071720531303CHARLESTON CHEW VANILLA 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 028000206604 100 GRAND KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000016 12CANADIANCRAWLERS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 7 12PK 0.00 9.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 611269546026 16oz SUGARFREE REDBULL 0.00 3.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 879982000854 1839 0.00 5.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 897782001727 1839 tubes 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 0189152 19th HOLE 0.00 7.29 0.00 0.00 0.00 s0189152 19TH HOLE SINGLE 0.00 1.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 1095 2 6PK @9.99 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 012615613612 2 DOGS ON BEACH ANNIVERSARY CARD 0.00 2.50 0.00 0.00 0.00 072084003758 2 PACK CANDY NECKLACE 0.00 0.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 851528000047 20TROUTWORMS 0.00 2.75 0.00 0.00 0.00 0407000 3 MUCKETEERS TRUFFLE CRISP 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0400030 3 MUSKETEEERS 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 040000473633 3 MUSKETEERS COCONUT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0406030 3 MUSKETEERS KING 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0405600 3 MUSKETEERS MINT 0.00 1.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 5 30 PACK 0.00 22.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 052000325522 32 Oz GATORADE - FIERCE STRAWBERRY 0.00 2.19 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170632867 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 71706337 4 ACES 0.00 9.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 077170633628 4 ACES GOLD 0.00 16.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 041387412154 4C BREAD CRUMBS 0.00 2.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222830 5 COBALT 0.00 2.99 0.00 0.00 0.00 022000013170 5 GUM 0.00 1.79 0.00 0.00 0.00 0222820 5 GUM COBALT -

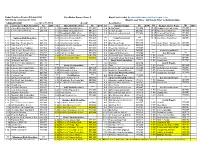

Pre-Order Form

Cedar Crest Ice Cream October 2020 Pre-Order Form - Page 2 Email your order to [email protected] 7269 Hwy 60, Cedarburg, WI 53012 Order Lead Time: 48 Hours Prior to Delivery Day 1-800-877-8341 Fax 262-377-5554 Acct #_____________ Acct Name:_______________________ Slv Cedar Crest Bulk Novelties No QTY Slv Mars Bulk Novelties No QTY Slv Sundae Cups No QTY Slv Budget $avers Pops No QTY 2-12 Choc-O-Chiller Malt Cup 001757 1-12 DoveBar Van/Milk Choc 001950 1-8 Butterfinger 001906 12-12 Sugar Free Twin Pops 001625 2-12 Cookies&Cream Cup 001758 1-12 DoveBar Van/Dark Choc 001951 1-8 Cookie Dough 001907 18-10 Assorted Twin Pops 001650 1-12 DoveBarAlm/Milk Choc 001952 1-8 Buncha Cookie Crunch 001908 18-10 Tropical Twin Pops 001651 1-48 Kind Cho Almond Sea Salt 001959 18-10 Banana Twin Pops 001652 *** Unilever Bulk Novelties *** 1-48 Kind Cho Peanut Butter 001960 *** Cedar Crest Retail *** 18-10 Root Beer Twin Pops 001653 1-12 B&J Cup Americone Dr 001729 1-12 Kind Smoothie Mango 001946 6-8 Vanilla Cups 001540 1-12 B&J Cup Chery Garcia 001735 1-12 Kind Smoothie Berry 001945 6-8 Blue Moon Cups 001542 10-6 Sonic Pops - Straw Lem 001584 1-12 B&J Cup C.C.C.D. 001737 1-24 M&M Vanilla Sandwich 001962 6-8 Rainbow Sherbet Cups 001543 10-6 Sonic Pops - Ocean Blue 001585 1-12 B&J Cup ChocFdgBrne 001736 1-48 Snicker's 2.8 oz 001970 6-8 Chocolate Malt Cups 001545 1-18 B&J Cookie Dough Slices 001716 1-24 Snicker's Cone 001971 6-8 Mint 'N Fudge Cups 001547 *** Cedar Crest BULK *** 1-18 B&J Tonight Dough Slices 001717 1-48 Twix 3. -

1801 Café at Ring •Eat Fresh, Eat Local•

1801 café at ring •eat fresh, eat local• Print Name: _________________________________________ Date: ________________________________ Apartment #:________________________________________ Signature: ___________________________ MENU FOR THE WEEK OF March 14th - March 20th Please place an “X” in the appropriate box to select the menu items you would like to order for the appropriate day of the week. Homemade Soups of Market Deli…5.00 each Sun Mon Tues Wed Thu Fri Sat the Day…1.50 Bagel & Lox Sunday Monday Turkey Sandwich Minestrone Italian Orzo Turkey Pastrami Sandwich Corned Beef Sandwich Tuesday Wednesday Salami Sandwich Tuscan Mulligatawny Chicken Chicken Salad Sandwich Tuna Salad Sandwich Thursday Friday Egg Salad Sandwich Leeks w/ Chicken Potatoes Noodle Hamburger Hot Dog Saturday Vegetable Burger Not available Beyond Burger Snacks Deli sandwiches come with coleslaw or a bag of chips, pickle and a can of Stacy’s Pita Chips…1.00 soda. Sandwiches are served with lettuce, tomatoes and onions. Cheeze It Snap’d…1.29 Bread Options: Cheez IT Original…0.79 Rye Pringles…1.09 Wheat Nutri Grain Bar…1.00 Pumpernickel Multi Grain Bread Hershey’s Dark White Gluten-Free: White Bread Chocolate…1.00 Sides Sun Mon Tues Wed Thu Fri Sat Hershey’s Milk Chocolate…1.00 French Fries…2.00 Hershey’s Mr. Fresh Fruit Cup…2.50 Goodbar…1.00 Egg Salad…2.50 Kit Kat…1.00 Reese’s…1.00 Chicken Salad…2.50 3 Musketeers…1.00 Tuna Salad…2.50 Twix…1.00 Almond Joy…1.00 Lunch delivery times are from 12:00pm-2:00pm. RXBAR…2.00 Please make payment arrangements with Belinda Desserts & Beverages on Barnum in the business office. -

Converted from /Dev/PCL

06/29/21 To Place an Order, Call (207)947-0321 Fax: (207)947-0323 ITEM # DESCRIPTION PACK ITEM # DESCRIPTION PACK COCKTAIL MIXES COFFEE FLAVORED 14678 ROLAND OLIVE JUICE DIRTY*MARTIN 12/25.4OZ 10927 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE JAMAICAN ME CRAZY 2 24/2.25OZ 2008 OCEAN SPRAY DRINK MIX BLOODY MARY 12/32 OZ 11282 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE VACATIONLND VANILLA 24/2.25OZ 26628 MAYSON'S MARGARITA MIX ON THE ROCKS 4/1 GAL 11516 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE HARBORSIDE HAZELNUT 24/2.25OZ 26633 MAYSON'S MARGARITA MIX FOR FROZEN 4/1 GAL 83931 NewEngland COFFEE REG FRNCH VAN CRAZE 24/2.5OZ 26634 MAYSON'S MARGARITA STRAWBERRY PUREE 4/1 GAL 83933 NewEngland COFFEE REG HAZELNUT CRAZE 24/2.5OZ 26637 MAYSON'S MARGARITA RASPBERRY PUREE 4/1 GAL 83939 NewEngland COFFEE REG PUMPKIN SPICE 24/2.5OZ 26639 MAYSON'S MARGARITA PEACH PUREE 4/1 GAL 83940 NewEngland COFFEE REG CINNAMON STICKY B 24/2.5OZ 26640 MAYSON'S MARGARITA WATERMELON PUREE 4/1 GAL 26724 MAYSON'S MARGARITA MANGO PUREE 4/1 GAL 83831 Packer DRINK MIX LEMON POWDER 12/1GAL COFFEE REGULAR 83890 COCO LOPEZ DRINK MIX CREAM COCONUT 24/15oz 10444 MAXWELL HOUSE COFFEE HOTEL & REST 112/1.6OZ 84011 Rose's SYRUP GRENADINE 12/1LTR 10479 Folgers COFFEE LIQ 100% COLOMBIAN 2/1.25L 10923 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE REG ACADIA BLEND 2O 42/2OZ 10924 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE REG COUNTY BLEND 1. 42/1.5OZ CAPPUCCINO 10930 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE REG DWNEAST DARK 2. 24/2.25OZ 90343 Int Coffee CAPPUCCINO FRENCH VAN 6/2LB 1410 Maxwellhse COFFEE REGULAR MASTERBLEND 64/3.75 OZ 23529 MAINE'S BEST COFFEE SEBAGO BLEND 42/2.25OZ 23531 NEW ENGLAND COFFEE EXTREME KAFFEINE -

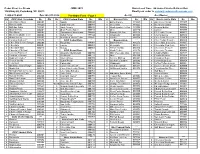

Cedar Crest Ice Cream JUNE 2021 Order Lead Time: 48 Hours Prior

Cedar Crest Ice Cream JUNE 2021 Order Lead Time: 48 Hours Prior to Delivery Day 7269 Hwy 60, Cedarburg, WI 53012 Email your order to [email protected] 1-800-877-8341 Fax 262-377-5554 Pre-Order Form - Page 1 Acct #_____________ Acct Name:_____________________ Slv CCIC 48oz. Scrounds No. Qty Slv CCIC Custard Pints No. Qty Slv Breyers Pints No. Qty Slv Ben & Jerry's Pints No. Qty 3 After Dinner Mint 000301 6 Vanilla 000840 8 Butter Pecan 001227 8 Americone Dream 000900 3 Banana Split 000329 6 Caramel Cone 000841 8 Chocolate 001225 8 Boom Chocolatta 000902 3 Birthday Cake 000331 6 Dark Secrets 000846 8 Heath English Toffee 001223 8 Brownie Batter 000905 3 Black Cherry 000302 6 #Luv Peanut Butter 000842 8 Oreo 001220 8 Cannoli 001008 3 Blue Moon 000303 6 Strawberry Cheesecake 000843 8 Reese's PB Cup 001228 8 CC Cookie Dough 000922 3 Blueberry Waffle Cone 000304 6 Butter Pecan 000844 8 Strawberry 001226 8 Cherry Garcia 000912 3 Butter Pecan 000305 6 Mint Mack Island Fudge 000845 8 Vanilla 001224 8 Choc Carm Cheezcke 000929 3 Caramel Collision® 000306 *** CCIC Sorbet Pints *** *** Breyers 48oz. *** 8 Choc Fudge Brownie 000914 3 Choc Chip Cookie Dough 000308 6 Raspberry 000860 6 Butter Pecan 001273 8 Choco Milk & Cookies 000937 3 Chocolate 000307 6 Lemon 000861 6 Chocolate 001274 8 Chocolate Chip Core 000942 3 Chocolate Malt 000310 6 Mango 000862 6 French Vanilla 001272 8 Chocolate Shake It 000933 3 Chocolate PB Swirl 000311 *** CCIC Round Pints *** 6 Heath Toffee 001279 8 Chocolate Therapy 000926 3 Coconut Explosion 000312 6 Amaretto -

Your Continued Donations Keep Wikipedia Running! List of Advertising Slogans

Your continued donations keep Wikipedia running! List of advertising slogans From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search The following is a partial list of advertising slogans in the English language: Contents [hide] • 1 Television, stations, network and cables • 2 Communications, broadcasting, and publishing • 3 Electronics • 4 Computing • 5 Recordings and Bands • 6 Retail stores • 7 Fashion o 7.1 Clothing o 7.2 Makeup o 7.3 Perfume o 7.4 Jewelry o 7.5 Sports Gear o 7.6 Miscellaneous • 8 Finance • 9 Food and drink • 10 Household • 11 Personal care • 12 Pharmaceutical & Healthcare • 13 Recreation, entertainment, and travel o 13.1 Stop smoking ads • 14 Transport o 14.1 Airlines o 14.2 Automobiles o 14.3 Automobile parts and accessories o 14.4 Automobile Tires o 14.5 Car rental o 14.6 Petroleum • 15 Government and military • 16 Social and public service • 17 Politics and advocacy • 18 Education • 19 Miscellaneous [edit] Television, stations, network and cables • "A new kind of family" - ABC Family • "ABC: America's Broadcasting Company" — ABC, 1999 • "Be the first to know" — CNN International, 2002-present • "Bringing weather to life" - The Weather Channel • "CTV. Canadian Television" — CTV • "Get Ready" - ITV1, 1989 • "GOTTALOVEIT" — Seven Network Australia, 2005-present • "It's not TV, it's HBO." — HBO, late 1990s • "It's Smart to be Square" — British Satellite Broadcasting, 1990, referring to its "squarial" satellite antennas • "It's time for U" — UPN, 2003 • "It's your ABC" - ABC 2002 • "Lifetime: Television for