Assumption of Risk Fuming{ Jamesf,Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case Against the Guest Statute

William & Mary Law Review Volume 7 (1966) Issue 2 Article 10 May 1966 The Case Against the Guest Statute O. Forrest Morgan Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Transportation Law Commons Repository Citation O. Forrest Morgan Jr., The Case Against the Guest Statute, 7 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 321 (1966), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol7/iss2/10 Copyright c 1966 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr THE CASE AGAINST THE GUEST STATUTE INTRODUCTION Lawes were not made for their own sakes, but for the sake of those who were to be guided by them; and though it is true they are and ought to be sacred, yet, if they be or are become unuseful for their end, they must either be amended if it may be, or new lawes be substituted.' During the late 1920's and early 1930's a number of American states enacted what have come to be called automobile "guest statutes" These acts provide essentially that in order for a guest passenger in an automobile to recover against the driver for injuries, sustained while riding in the vehicle, he must prove the operator negligent to some specified degree above and beyond what is termed "ordinary negli- gence." 3 The statute usually requires a showing of wantoness, will- fulness or gross negligence. In essence this legislation serves simply to relieve the driver of his duty of reasonable care for the safety of his fellow man. -

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

Recent Cases

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 26 Issue 2 Issue 2 - March 1973 Article 4 3-1973 Recent Cases Law Review Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Law Review Staff, Recent Cases, 26 Vanderbilt Law Review 340 (1973) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol26/iss2/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT CASES Conflict of Laws-Torts-Lex Loci Delicti Is Proper Law When Parties Are Domiciled in Different Juris- dictions Unless Displacing That Law Advances Forum State's Substantive Law Purposes Without Impeding Interstate Relations or Predictability of Result Plaintiff, an Ontario domiciliary, brought an action in New York for the wrongful death of her husband, also a domiciliary of Ontario, who was killed in a collision in that province' while a passenger in an automobile driven by defendant's2 intestate, a New York domiciliary.3 Defendant pleaded as an affirmative defense the Ontario guest statute, 4 which restricts a guest's recovery to damages for injuries sustained only as a result of his host's gross negligence. Plaintiff argued that because it conflicted with the policy of the New York guest statute,5 the Ontario statute was inapplicable, and moved to dismiss the defense. -

Chapter 668 Liability in Tort — Comparative Fault

1 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT, §668.3 CHAPTER 668 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT Referred to in §321J.4B, 625.21 668.1 Fault defined. 668.11 Disclosure of expert witnesses 668.2 Party defined. in liability cases involving 668.3 Comparative fault — effect — licensed professionals. payment method. 668.12 Liability for products — defenses. 668.4 Joint and several liability. 668.13 Interest on judgments. Evidence of previous payment or 668.5 Right of contribution. 668.14 future right of payment. 668.6 Enforcement of contribution. 668.14A Recoverable damages for medical 668.7 Effect of release. expenses. 668.8 Tolling of statute. 668.15 Damages resulting from sexual 668.9 Insurance practice. abuse — evidence. 668.10 Governmental exemptions. 668.16 Applicability of this chapter. 668.1 Fault defined. 1. As used in this chapter, “fault” means one or more acts or omissions that are in any measure negligent or reckless toward the person or property of the actor or others, or that subject a person to strict tort liability. The term also includes breach of warranty, unreasonable assumption of risk not constituting an enforceable express consent, misuse of a product for which the defendant otherwise would be liable, and unreasonable failure to avoid an injury or to mitigate damages. 2. The legal requirements of cause in fact and proximate cause apply both to fault as the basis for liability and to contributory fault. 84 Acts, ch 1293, §1 See also §619.17 668.2 Party defined. As used in this chapter, unless otherwise required, “party” means any of the following: 1. -

Assumption of Risk, Waiver, and Release of Liability

Rev. 4/30/2020 ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER, AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY READ THIS ASSUMPTION OF RISK, WAIVER AND RELEASE OF LIABILITY BEFORE YOU SIGN IT. IT AFFECTS YOUR LEGAL RIGHTS. I, ____________________________ [print student’s name], agree to act in a responsible and safe manner during my participation in the ____________________________ “the Program.” I acknowledge and agree that I must comply with the rules and requirements of the Program, any other applicable University policy, and all applicable local, state, and federal law. I agree to follow the instructions issued by Program directors and staff. I will also abide by signage posted on the University’s campus. I understand that I may be dismissed from the Program for misconduct. I understand that my participation in the Program is voluntary, and I may be exposed to risks and hazards that could result in serious illness, bodily injury, disability, or death. These risks and hazards may include, but are not limited to: (i) vehicular, pedestrian, or other accidents, such as drowning, (ii) storms, floods, fires, earthquakes, and other natural disasters, (iii) infectious diseases or viruses, including but not limited to COVID-19, (iv) limited or inadequate medical care, (v) inadequate design, safety, and maintenance of buildings and public places, (vi) terrorist activities, and (vii) allergic reactions to food, insects, or other allergens. I also understand that during the Program I may use or access educational computer applications, web-based services, or online content that could expose me to certain cyber risks, including but not limited to, cyber predators, data mining, phishing, viruses, malware, data breaches, cyberbullying, exploitation, victimization, cyber stalking, online grooming, reputational loss, brand hijacking, and image replication. -

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1

Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline 1. Introduction 2. The Basis of Tort Law 3. Intentional Torts 4. Negligence 5. Cyber Torts: Defamation Online 6. Strict Liability 7. Product Liability 8. Defenses to Product Liability 9. Tort Law and the Paralegal Chapter Objectives After completing this chapter, you will know: • What a tort is, the purpose of tort law, and the three basic categories of torts. • The four elements of negligence. • What is meant by strict liability and under what circumstances strict liability is applied. • The meaning of strict product liability and the underlying policy for imposing strict product liability. • What defenses can be raised in product liability actions. Chapter 7 Tort Law and Product Liability Chapter Outline I. INTRODUCTION A. Torts are wrongful actions. B. The word tort is French for “wrong.” II. THE BASIS OF TORT LAW A. Two notions serve as the basis of all torts. i. Wrongs ii. Compensation B. In a tort action, one person or group brings a personal-injury suit against another person or group to obtain compensation or other relief for the harm suffered. C. Tort suits involve “private” wrongs, distinguishable from criminal actions that involve “public” wrongs. D. The purpose of tort law is to provide remedies for the invasion of various interests. E. There are three broad classifications of torts. i. Intentional Torts ii. Negligence iii. Strict Liability F. The classification of a particular tort depends largely on how the tort occurs (intentionally or unintentionally) and the surrounding circumstances. Intentional Intentions An intentional tort requires only that the tortfeasor, the actor/wrongdoer, intended, or knew with substantial certainty, that certain consequences would result from the action. -

Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory Into Tort Doctrine John L

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Faculty Scholarship 1991 Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine John L. Diamond UC Hastings College of the Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation John L. Diamond, Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine, 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Available at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/faculty_scholarship/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Publications UC Hastings College of the Law Library Diamond John Author: John L. Diamond Source: Ohio State Law Journal Citation: 52 Ohio St. L.J. 717 (1991). Title: Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine Originally published in OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL. This article is reprinted with permission from OHIO STATE LAW JOURNAL and Ohio State University Michael E. Moritz College of Law. Assumption of Risk After Comparative Negligence: Integrating Contract Theory into Tort Doctrine JOHN L. DIAMOND* I. INTRODUCTION The confusion generated by the doctrine of assumption of risk' is illustrated by the contradicting responses to the following hypothetical: - 0 1991 John L. Diamond. Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law. B.A., Yale College; J.D., Columbia Law School; Dip. -

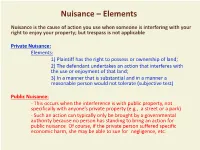

Nuisance – Elements

Nuisance – Elements Nuisance is the cause of action you use when someone is interfering with your right to enjoy your property; but trespass is not applicable Private Nuisance: Elements: 1) Plaintiff has the right to possess or ownership of land; 2) The defendant undertakes an action that interferes with the use or enjoyment of that land; 3) In a manner that is substantial and in a manner a reasonable person would not tolerate (subjective test) Public Nuisance: - This occurs when the interference is with public property, not specifically with anyone’s private property (e.g., a street or a park) - Such an action can typically only be brought by a governmental authority because no person has standing to bring an action for public nuisance. Of course, if the private person suffered specific economic harm, she may be able to sue for negligence, etc. Nuisance - Other Factors - The nuisance must have arisen from an act that’s actionable as an intentional, negligent or strict liability tort! - The actions that give rise to the nuisance must be “unreasonable” under the circumstances. Thus: A “balancing test” must be performed between the harm that the nuisance causes and the benefits of the activities that create the nuisance, taking into account: o The economic and social importance of the activity o The burden on the defendant and on society of forcing the activity to cease o Whether there is a more appropriate place to conduct the activity - All the rules regarding causation and damages apply, as with negligence and strict liability - The defenses of assumption of risk and contributory negligence apply; as with any other tort. -

Symposium: Introduction: Genuine Tort Reform

Roger Williams University Law Review Volume 13 Issue 1 Vol. 13: No. 1 (Winter 2008) - Article 1 Symposium: Genuine Tort Reform Winter 2008 Symposium: Introduction: Genuine Tort Reform Carl T. Bogus Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bogus, Carl T. (2008) "Symposium: Introduction: Genuine Tort Reform," Roger Williams University Law Review: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://docs.rwu.edu/rwu_LR/vol13/iss1/1 This Symposia is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Roger Williams University Law Review by an authorized editor of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Symposium Introduction: Genuine Tort Reform Carl T. Bogus* I am not sure who coined the term "tort reform," but as far as I know it was first used in 1974 in a student article published by the UCLA Law Review. 1 That article was very much a Sixties piece. The author praised Justice Roger Traynor and the California Supreme Court for their leadership in "placing tort liability on the party who is best able to spread the risk of loss." She continued: Though judicial activism is generally regarded by traditional legal process scholars as undesirable, in tort law, it appears to be an appropriate fulfillment of the historical function of the common law-to meld the precedents of the past and needs and concerns of the present. 2 For nearly a decade thereafter, "tort reform" was still occasionally used to refer to efforts to make the tort system more dynamic by making it easier for victims to hold accountable 3 wrongdoers and those who were in a position to prevent harm. -

Capacity of Minors to Be Chargeable with Negligence and Their Ts Andard of Care T

Nebraska Law Review Volume 57 | Issue 3 Article 7 1978 Capacity of Minors to Be Chargeable with Negligence and Their tS andard of Care T. Edward Icenogle University of Nebraska College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation T. Edward Icenogle, Capacity of Minors to Be Chargeable with Negligence and Their Standard of Care, 57 Neb. L. Rev. 763 (1978) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol57/iss3/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Comment Capacity of Minors to be Chargeable with Negligence And Their Standard of Care The infant is favored by the law not so much on his lack of knowledge as because1 of indiscretion,imprudence, lack of judgment, and impul- siveness. I. INTRODUCTION Nebraska law, like that of other American jurisdictions, be- stows considerable favoritism upon children. Although a minor, like an adult, may sue2 or be sued, 3 the minor is the subject of legal favoritism predicated on the disability of infancy which has long been recognized at common law.4 This favoritism is obvious in the special treatment accorded youthful criminal offenders; 5 in contract law, under which the contracts of minors are in some cases voidable; 6 in the law of intentional tort;7 and in the law of negligent tort.8 It is the last of these examples of favoritism-the special consideration given minors in the law of negligence-which is the topic of this comment. -

MASS TORTS at the NEUTRAL FORUM: a CRITICAL ANALYSIS of the ALI’S PROPOSED CHOICE RULE 56 Albany L

MASS TORTS AT THE NEUTRAL FORUM: A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE ALI’S PROPOSED CHOICE RULE 56 Albany L. Rev. 807 (1993) * Louise Weinberg TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTORY..........................................................809 A. Conflict, crisis, and confusion at the ALI....................809 A motion is defeated....................................................809 The policy problem......................................................811 The irrationality problem.............................................811 B. The proposed liability choice rule for mass tort ........812 The problem of mass litigation disaster in mass disaster litigation......................................................812 The neutral forum and the choice-of-law process .......813 The draft liability choice rule: Its setting ....................814 The draft liability choice rule: Its shape ......................814 II. A CRITIQUE FROM POLICY........................................816 A. Policy at the neutral mass tort forum.........................816 Whatever happened to policy?....................................816 A positivist’s question: Whose policy?......................817 B. National policy and the remedial choice....................818 What is national policy in mass tort cases? .................818 National conflicts policy..............................................819 The defense bias of “neutral” choice rules..................819 The defense bias of “neutral” choice rules..................819 The problem of the impolitic or dangerous choice......822 -

Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk-- the Ac Se for Their Em Rger Minn

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1971 Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk-- The aC se for Their eM rger Minn. L. Rev. Editorial Board Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Editorial Board, Minn. L. Rev., "Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk--The asC e for Their eM rger" (1971). Minnesota Law Review. 2996. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2996 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Note: Contributory Negligence and Assumption of Risk- The Case for Their Merger I. INTRODUCTION At common law the plaintiff in a negligence action was barred from recovery when his conduct constituted either con- tributory negligence or assumption of risk. As a result of the adoption of a comparative negligence statute in Minnesota,' con- tributory negligence no longer completely bars recovery but only reduces recoverable damages. The statute, however, is silent as to assumption of risk. Since the purpose of the statute is to al- low a plaintiff to recover part of his damages despite the fact that his conduct fails to meet the reasonable man standard of care, as long as his negligence is less than that of the defendant, and since both contributory negligence and assumption of risk describe unreasonable conduct by the plaintiff, the purpose of the comparative negligence statute would be frustrated if assumption of risk continued to operate as a complete bar to recovery.