UKHR Briefing 2019 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brexit and Local Government

House of Commons Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee Brexit and local government Thirteenth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 1 April 2019 HC 493 Published on 3 April 2019 by authority of the House of Commons Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee The Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Current membership Mr Clive Betts MP (Labour, Sheffield South East) (Chair) Bob Blackman MP (Conservative, Harrow East) Mr Tanmanjeet Singh Dhesi MP (Labour, Slough) Helen Hayes MP (Labour, Dulwich and West Norwood) Kevin Hollinrake MP (Conservative, Thirsk and Malton) Andrew Lewer MP (Conservative, Northampton South) Teresa Pearce MP (Labour, Erith and Thamesmead) Mr Mark Prisk MP (Conservative, Hertford and Stortford) Mary Robinson MP (Conservative, Cheadle) Liz Twist MP (Labour, Blaydon) Matt Western MP (Labour, Warwick and Leamington) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/copyright/ Committee’s reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/hclg and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committees’ websites. -

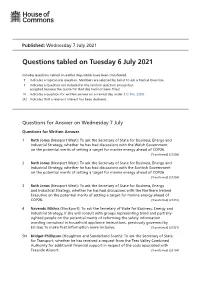

Questions Tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021

Published: Wednesday 7 July 2021 Questions tabled on Tuesday 6 July 2021 Includes questions tabled on earlier days which have been transferred. T Indicates a topical oral question. Members are selected by ballot to ask a Topical Question. † Indicates a Question not included in the random selection process but accepted because the quota for that day had not been filled. N Indicates a question for written answer on a named day under S.O. No. 22(4). [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. Questions for Answer on Wednesday 7 July Questions for Written Answer 1 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Welsh Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27308) 2 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Scottish Government on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27309) 3 Ruth Jones (Newport West): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, whether he has had discussions with the Northern Ireland Executive on the potential merits of setting a target for marine energy ahead of COP26. [Transferred] (27310) 4 Navendu Mishra (Stockport): To ask the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, if she will consult with groups representing blind and partially- sighted people on the potential merits of reforming the safety information wording contained in household appliance instructions, previously governed by EU law, to make that information more inclusive. -

Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election

Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election Dr Robert Ford, Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE), The University of Manchester Ruth Grove-White, Migrants’ Rights Network Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election Content 1. Introduction 2 2. This briefing 4 3. Migrant voters and UK general elections 5 4. Migrant voters in May 2015 6 5. Where are migrant voters concentrated? 9 6. Where could migrant votes be most influential? 13 7. Migrant voting patterns and intentions 13 8. Conclusion 17 9. Appendix 1: Methodology 18 10. References 19 1. Migrant Voters in the 2015 General Election 1. Introduction The 2015 general election looks to be the closest and least predictable in living memory, and immigration is a key issue at the heart of the contest. With concerns about the economy slowly receding as the financial crisis fades into memory, immigration has returned to the top of the political agenda, named by more voters as their most pressing political concern than any other issue1. Widespread anxiety about immigration has also been a key driver behind the surge in support for UKIP, though it is far from the only issue this new party is mobilizing around2. Much attention has been paid to the voters most anxious about immigration, and what can be done to assuage their concerns. Yet amidst this fierce debate about whether, and how, to restrict immigration, an important electoral voice has been largely overlooked: that of migrants themselves. In this briefing, we argue that the migrant The political benefits of engaging with electorate is a crucial constituency in the 2015 migrant voters could be felt far into the election, and will only grow in importance in future. -

Understanding Governments Attitudes to Social Housing

Understanding Government’s Attitudes to Social Housing through the Application of Politeness Theory Abstract This paper gives a brief background of housing policy in England from the 2010 general election where David Cameron was appointed Prime Minister of a Coalition government with the Liberal Democrats and throughout the years that followed. The study looks at government attitudes towards social housing from 2015, where David Cameron had just become Prime Minister of an entirely Conservative Government, to 2018 following important events such as Brexit and the tragic Grenfell Tower fire. Through the application of politeness theory, as originally put forward by Brown & Levinson (1978, 1987), the study analysis the speeches of key ministers to the National Housing Summit and suggests that the use of positive and negative politeness strategies could give an idea as to the true attitudes of government. Word Count: 5472 Emily Pumford [email protected] Job Title: Researcher 1 Organisation: The Riverside Group Current research experience: 3 years Understanding Government’s Attitudes to Social Housing through the Application of Politeness Theory Introduction and Background For years, the Conservative Party have prided themselves on their support for home ownership. From Margaret Thatcher proudly proclaiming that they had taken the ‘biggest single step towards a home-owning democracy ever’ (Conservative Manifest 1983), David Cameron arguing that they would become ‘once again, the party of home ownership in our country’ (Conservative Party Conference Speech 2014) and Theresa May, as recently as 2017, declaring that they would ‘make the British Dream a reality by reigniting home ownership in Britain’ (Conservative Party Conference Speech 2017). -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 11 January 2018 On 8-9 January 2018, Prime Minister Theresa May conducted a ministerial reshuffle. This guide has been updated to reflect the changes. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets, as well as Brexit and security matters, which are likely to dominate most of the current Parliament. This gives the government a working majority of 13. This is a briefing for BIA members on the new Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. Contents Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009

Ministerial Reshuffle – 5 June 2009 8 June 2009 This note provides details of the Cabinet and Ministerial reshuffle carried out by the Prime Minister on 5 June following the resignation of a number of Cabinet members and other Ministers over the previous few days. In the new Cabinet, John Denham succeeds Hazel Blears as Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government and John Healey becomes Housing Minister – attending Cabinet - following Margaret Beckett’s departure. Other key Cabinet positions with responsibility for issues affecting housing remain largely unchanged. Alistair Darling stays as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Lord Mandelson at Business with increased responsibilities, while Ed Miliband continues at the Department for Energy and Climate Change and Hilary Benn at Defra. Yvette Cooper has, however, moved to become the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions with Liam Byrne becoming Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills has been merged with BERR to create a new Department for Business, Innovation and Skills under Lord Mandelson. As an existing CLG Minister, John Healey will be familiar with a number of the issues affecting the industry. He has been involved with last year’s Planning Act, including discussions on the Community Infrastructure Levy, and changes to future arrangements for the adoption of Regional Spatial Strategies. HBF will be seeking an early meeting with the new Housing Minister. A full list of the new Cabinet and other changes is set out below. There may yet be further changes in junior ministerial positions and we will let you know of any that bear on matters of interest to the industry. -

Unlocking the Potential of the Global Marine Energy Industry 02 South West Marine Energy Park Prospectus 1St Edition January 2012 03

Unlocking the potential of the global marine energy industry 02 South West Marine Energy Park Prospectus 1st edition January 2012 03 The SOUTH WEST MARINE ENERGY PARK is: a collaborative partnership between local and national government, Local Enterprise Partnerships, technology developers, academia and industry a physical and geographic zone with priority focus for marine energy technology development, energy generation projects and industry growth The geographic scope of the South West Marine Energy Park (MEP) extends from Bristol to Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, with a focus around the ports, research facilities and industrial clusters found in Cornwall, Plymouth and Bristol. At the heart of the South West MEP is the access to the significant tidal, wave and offshore wind resources off the South West coast and in the Bristol Channel. The core objective of the South West MEP is to: create a positive business environment that will foster business collaboration, attract investment and accelerate the commercial development of the marine energy sector. “ The South West Marine Energy Park builds on the region’s unique mix of renewable energy resource and home-grown academic, technical and industrial expertise. Government will be working closely with the South West MEP partnership to maximise opportunities and support the Park’s future development. ” Rt Hon Greg Barker MP, Minister of State, DECC The South West Marine Energy Park prospectus Section 1 of the prospectus outlines the structure of the South West MEP and identifies key areas of the programme including measures to provide access to marine energy resources, prioritise investment in infrastructure, reduce project risk, secure international finance, support enterprise and promote industry collaboration. -

Cabinet Committees

Published on The Institute for Government (https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk) Home > Whitehall Explained > Cabinet committees Cabinet committees What are cabinet committees? Cabinet committees are groups of ministers that can “take collective decisions that are binding across government”.[1] They are partly designed to reduce the burden on the full cabinet by allowing smaller groups of ministers to take decisions on specific policy areas. These committees have been around in some form since the early 20th century. The government can also create other types of ministerial committees. In June 2015, David Cameron introduced implementation taskforces, designed “to monitor and drive delivery of the government’s most important cross-cutting priorities”[2], although these were discontinued when Boris Johnson became prime minister in July 2019. In March 2020, Boris Johnson announced the creation of four new ‘implementation committees’[3] in response to the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. These four committees focused on healthcare, the general public sector, economic and business, and international response. The four committees were chaired by Health Secretary Matt Hancock, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Michael Gove, Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak and Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab respectively. Each committee chair fed into a daily ‘C-19 meeting’ of the prime minister, key ministers and senior officials, to discuss Covid-19. These ‘implementation committees’ were replaced by two new Covid-19 related cabinet committees in June 2020 – ‘COVID-19 Strategy’ and ‘COVID-19 Operations’. On 13 May 2020, the Cabinet Office also announced the creation of five new ‘roadmap taskforces’[4] – committees intended to help guide certain sectors of the UK economy out of the Covid-19 induced lockdown. -

18 September 2006 Council Minutes

Agenda item: 2a CROYDON COUNCIL MINUTES MEETING OF THE COUNCIL HELD ON Monday, 18 July 2011 at 6.30pm in the Council Chamber, Town Hall. THE MAYOR, COUNCILLOR GRAHAM BASS – PRESIDING Councillors Arram, Avis, Ayres, Bashford, Bee, Bonner, Butler, Buttinger, Chatterjee, Chowdhury, Clouder, Collins, Cromie, Cummings, Fisher, Fitze, Fitzsimons, Flemming, Gatland, Godfrey, Gray, Hale, Hall, Harris, Hay-Justice, Hoar, Hollands, Hopley, Jewitt, Kabir, Kellett, B Khan, , Kyeremeh, Lawlor, Lenton, Letts, Mansell, Marshall, D Mead, M Mead, Mohan, Neal, Newman, O’Connell, Osland, Parker, Pearson, Perry, H Pollard, T Pollard, Rajendran, G Ryan, P Ryan, Selva, Scott, Shahul-Hameed, Slipper, Smith, Speakman, Thomas, Watson, Wentworth, Winborn, Woodley and Wright. Absent: Councillors Bains, George-Hilley, S Khan and Quadir 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE (agenda item 1) Apologies for absence were received from Councillor Shafi Khan 2. MINUTES (agenda item 2) RESOLVED that the Minutes of the Annual Council Meeting held on 23 May 2011 be signed as a correct record. 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS (agenda item 3) All Members of the Council confirmed that their interests as listed in their Annual Declaration of Interests Forms were accurate and up-to-date. Council Sara Bashford declared a personal interest in agenda item 6 (PQ 040) as she mentioned Gavin Barwell MP in her reply to the question and she works for him. Councillor Janet Marshall declared a personal interest in agenda item 10 as co-opted Governor of Quest Academy; C20110718 min 1 Councillor Margaret Mead declared a personal interest in agenda item 10 as a Governor of Whitgift Foundation. 4. URGENT BUSINESS (agenda item number 4) Councillor Tony Newman moved that the Extraordinary Council Meeting be brought forward as urgent business. -

Confidence Now Building As Town Attracts Investors

Big success Confidence now as cycling building as town elite speed attracts investors PROMINENT investors are across town tapping into Croydon’s potential with a succession of THOUSANDS of people lined the major deals helping to change streets of Croydon as the town hosted the face of the town. a hugely successful round of cycling’s elite team competition on Tuesday, Consultant surveyor Vanessa June 2. Clark (pictured) believes deals such as Hermes Investment The town was the subject of an Management’s purchase of the hour-long highlights package on recently-refurbished Number ITV4 after hosting round three of the One Croydon, one of the town’s women’s Matrix Fitness Grand Prix most iconic buildings, are and round seven of the men’s Pearl “game-changing” in terms of Izumi Tour Series. the way the town is being And the event got people talking perceived. about Croydon in a fresh light as, “The good news is that quality central London what the experts described as a investors now see Croydon as an attractive “hugely-technical” circuit produced a proposition,”she said. “A s confidence in the town thrilling evening’s racing. has improved, so have prices.” Council leader Tony Newman and The so-called 50p Building, designed by Richard Mayor of Croydon Councillor Seifert, changed hands in a reported £36 million Patricia Hay-Justice were among the deal, bringing Hermes’ investment in the town this presentation teams. WHEELS IN MOTION: The cycling tour events held in Croydon earlier this month were hailed as a success year to around £70 million, having already acquired the Grants Entertainment Centre in High Street, which features a 10-screen Vue Cinema, health club, bars and restaurants.