Competition with Switching Costs and Network Effects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NETWORK EFFECTS Welfare Even Though No Explicit Compensation Accounts for This

From the book Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World. By David Easley and Jon Kleinberg. Cambridge University Press, 2010. Complete preprint on-line at http://www.cs.cornell.edu/home/kleinber/networks-book/ Chapter 17 Network Effects At the beginning of Chapter 16, we discussed two fundamentally different reasons why individuals might imitate the behavior of others. One reason was based on informational effects: since the behavior of other people conveys information about what they know, observ- ing this behavior and copying it (even against the evidence of one’s own private information) can sometimes be a rational decision. This was our focus in Chapter 16. The other reason was based on direct-benefit effects, also called network effects: for some kinds of decisions, you incur an explicit benefit when you align your behavior with the behavior of others. This is what we will consider in this chapter. A natural setting where network effects arise is in the adoption of technologies for which interaction or compatibility with others is important. For example, when the fax machine was first introduced as a product, its value to a potential consumer depended on how many others were also using the same technology. The value of a social-networking or media- sharing site exhibits the same properties: it’s valuable to the extent that other people are using it as well. Similarly, a computer operating system can be more useful if many other people are using it: even if the primary purpose of the operating system itself is not to interact with others, an operating system with more users will tend to have a larger amount of software written for it, and will use file formats (e.g. -

Network Economics, Transaction Costs, and Dynamic Competition

Network Economics, Vertical Integration, and Regulation Howard Shelanski May 2012 1 New Institutional Economics Key concern is governance of transactions, not price and output. Unit of analysis is the transaction Key question: why a transaction is (or should be) organized or mediated by one institution as opposed to another: Markets vs “hierarchies” E.g., a firm’s make or buy decision: why does a firm buy some things and make others? 2 Origins Ronald Coase Key lessons Property Rights/Default Rules and Transaction Costs Matter Facts and Institutions Matter Oliver Williamson Institutions have differing competencies for governing transactions in the presence of transaction costs 3 Key Assumptions of the New Institutional Economics Bounded rationality: economic actors intend to be rational but are only limitedly so. Opportunism: economic actors will expect others to act opportunistically and seek mechanisms (institutions) to protect themselves from hold-up. Asset specificity: Specific investment is the key variable that allows opportunism and drives firms from markets toward hierarchical institutions. 4 The “Coase Theorum” Pollution example: a plant pollutes and imposes costs on a nearby farm. To what extent should the plant be allowed to pollute or the farmer be allowed to keep farming? theorum version 1: As long as both parties are free to bargain, the final amount of pollution not depend on the initial allocation of property rights. theorum version 2: when transactions costs exist, the final amount of pollution depends on the initial allocation of property rights. 5 Lessons and Policy Implications Institutions arise to economize on transaction costs. Sometimes private bargaining is best, at other times other institutions are more efficient. -

Platform Envelopment Working Paper

Platform Envelopment Thomas Eisenmann Geoffrey Parker Marshall Van Alstyne Working Paper 07-104 Copyright © 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 by Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, and Marshall Van Alstyne Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Platform Envelopment Thomas Eisenmann, Geoffrey Parker, Marshall Van Alstyne Revised, July 27 2010 ABSTRACT Due to network effects and switching costs in platform markets, entrants generally must offer revolutionary functionality. We explore a second entry path that does not rely upon Schumpeterian innovation: platform envelopment. Through envelopment, a provider in one platform market can enter another platform market, combining its own functionality with the target’s in a multi-platform bundle that leverages shared user relationships. We build upon the traditional view of bundling for economies of scope and price discrimination and extend this view to include the strategic management of a firm's user network. Envelopers capture share by foreclosing an incumbent’s access to users; in doing so, they harness the network effects that previously had protected the incumbent. We present a typology of envelopment attacks based on whether platform pairs are complements, weak substitutes or functionally unrelated, and we analyze conditions under which these attack types are likely to succeed. Keywords: Market entry, platforms, network effects, bundling, foreclosure Acknowledgements: Funding from NSF grant SES-0925004 is gratefully acknowledged. Thomas Eisenmann Geoffrey Parker Marshall Van Alstyne Professor Associate Professor Associate Professor Harvard Business School Freeman School of Business Boston University SMG Rock Center 218 Tulane University 595 Commonwealth Ave. -

Critical Mass and Network Evolution in Telecommunications

Forthcoming in Toward a Competitive Telecommunications Industry: Selected Papers from the 1994 Telecommunications Policy Research Conference, Gerard Brock (ed.), 1995. Critical Mass and Network Evolution in Telecommunications by Nicholas Economides and Charles Himmelberg December 1994 Abstract Network goods exhibit positive consumption externalities, commonly known as "network externalities." In markets, this fact can give rise to the existence of a critical mass point, that is, a minimum network size that can be sustained in equilibrium, given the cost and market structure of the industry. In this paper, we describe the conditions under which a critical mass point exists for a network good. We also characterize the existence of critical mass points under various market structures. Surprisingly, neither existence nor the size of the minimum feasible network depends on market structure. Thus, even though a monopolist enjoys an additional degree of freedom through its influence over expectations, and even though monopolistic and oligopolistic markets will in general provide a smaller sized network than perfect competition, the critical mass point is nonetheless the same. We extend these results by making the model dynamic and by generalizing it to allow durable goods. Introducing network externalities to a dynamic model of market growth increases the speed at which market demand grows in the presence of a downward time trend for industry marginal cost. We use this prediction to calibrate the model and obtain estimates of the parameter measuring a consumer’s valuation of the installed base (i.e., the network effect) using aggregate time series data on prices and quantities in the US fax market. -

Network Effects on Tweeting

Network Effects on Tweeting Jake T. Lussier and Nitesh V. Chawla Interdisciplinary Center for Network Science and Applications (iCeNSA), University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA {jlussier,nchawla}@nd.edu http://www.nd.edu/∼(jlussier,nchawla)/ Abstract. Online social networks (OSNs) have created new and exciting ways to connect and share information. Perhaps no site has had a more profound effect on information exchange than Twitter.com. In this pa- per, we study large-scale graph properties and lesser-studied local graph structures of the explicit social network and the implicit retweet network in order to better understand the relationship between socialization and tweeting behaviors. In particular, we first explore the interplay between the social network and user tweet topics and offer evidence that suggests that users who are close in the social graph tend to tweet about simi- lar topics. We then analyze the implicit retweet network and find highly unreciprocal links and unbalanced triads. We also explain the effects of these structural patterns on information diffusion by analyzing and vi- sualizing how URLs tend to be tweeted and retweeted. Finally, given our analyses of the social network and the retweet network, we provide some insights into the relationships between these two networks. Keywords: Data mining, social networks, information diffusion. 1 Introduction A microblogging service launched in 2006, Twitter.com has since grown into one of the most popular OSNs on the web and one of the most prominent technologi- cal influences on modern society. Twitter is not only an environment for social tie formation, but also for information exchange and dissemination. -

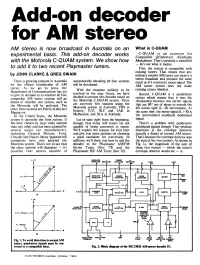

Add-On Decoder for AM Stereo AM Stereo Is Now Broadcast in Australia on an What Is C-QUAM Experimental Basis

Add-on decoder for AM stereo AM stereo is now broadcast in Australia on an What is C-QUAM experimental basis. This add-on decoder works C-QUAM is an acronym for Compatible QUadrature Amplitude with the Motorola C-QUAM system. We show how Modulation. That's certainly a mouthful — let's see what it means. to add it to two recent Playmaster tuners. First, the system is compatible with existing tuners. That means that any by JOHN CLARKE & GREG SWAIN ordinary (mono) AM tuner can receive a stereo broadcast and produce the same There is growing pressure in Australia automatically decoding all four systems result as if it received a mono signal. The for the official introduction of AM will be developed. AM stereo system does not make stereo. As we go to press, the existing tuners obsolete. Department of Communications has yet With the situation unlikely to be to give its decision as to whether all four resolved in the near future, we have Second, C-QUAM is a quadrature decided to present this decoder based on competing AM stereo systems will go system which means that it uses the the Motorola C-QUAM system. There ahead or whether one system, such as relationship between two carrier signals are currently five stations using the the Motorola, will be preferred. The that are 90° out of phase to encode the Motorola system in Australia: 2WS in left minus right (L — R) information. At other three systems are Harris, Kahn and Sydney; 3UZ, 3KZ and 3AK in Magnavox. the same time, the mono signal (L + R) is Melbourne; and 5KA in Adelaide. -

Kosiba Voted Ark Board 25 Per Copy VOL 24 NO 49 the Iuo, THURSDAY MAY 21Rn Flmiuhlihhiiwflihuiiohiíiuiàiniwuui11fflu11n 111M Buy A:

- - -;;T=---?,--------- ********************************************************* ' - . - . ,. , *' MEMORIAL DAY* * Merch*ntsandOrganizatiónal $ponorship Financial Instliution Sponsorship * Pages 22.26 Päges**r*************************************************W**** 16-17 ' Niles and Mill Run come to terms ' Library commends onwheelchair placement Community Outreach program by ElleeisHlrscbfeld , byDlane Miller decisIon last Friday on a legalHerbert, architect designer and ' placement nf wheelchair palrom slorhholdr in Tiffany Produr- Merle Ronenblalt, Nilesdistrict's "communitY outreach" With Nues Village officials meeting of. - breathmg firedown their necks, in the playhouse. -lions -sparred with village of- LibraryDistrictemployee,program at a May 13 Mill Run personnel came to a Representing Mill Ras, Jim toiibiuiedon Page37 reported on the pacress of the ConllnuedonPageti Arnold named Kosiba voted ark Board 25 per copy VOL 24 NO 49 THE iuo, THURSDAY MAY 21rn flmIUhlIHhiiWflIHuiiOhIÍIuIàINIWuUi11fflU11n 111m Buy A: -. iuer.i. S::. ratherthanvote for himself. I..F.am:the -Dan Kosiha sgas reelected to. Kosiba was nominated -for a - his third - term as - Niles Park . third term as president by - - , Board President during Tnesday Beasse. : .. Pop nigkt'nParkBoardmeetiiig-- -- Bud4y PY - Votmg foKnsiba w Pa k Newly elected Commissioner .:BoardCoinminsSnners WalterJim Piershi nominated Beasse . byDavid(Bu d)Bessér - -- : ',.-.Day, .-5O,,,-M,.,-,,00k-,.und -for the presidency and wan the . - -Coi,llnued on Page 38 w renots ewbethe tsanewphmenabtweve -

An Overview of Social Networks and Economic Applications∗

An Overview of Social Networks and Economic Applications∗ Matthew O. Jackson† Final Version: June 25, 2010 Written for the Handbook of Social Economics‡ Abstract In this chapter I provide an overview of research on social networks and their role in shaping behavior and economic outcomes. I include discussion of empirical and the- oretical analyses of the role of social networks in markets and exchange, learning and diffusion, and network games. I also include some background on social network char- acteristics and measurements, models of network formation, models for the statistical analysis of social networks, as well as community detection. Keywords: Social Networks, Network Games, Graphical Games, Games on Net- works, Diffusion, Learning, Network Formation, Community Detection, JEL Classification Codes: D85, C72, L14, Z13 1 Introduction The people with whom we interact on a regular basis, and even some with whom we in- teract only sporadically, influence our beliefs, decisions and behaviors. Examples of the effects of social networks on economic activity are abundant and pervasive, including roles in transmitting information about jobs, new products, technologies, and political opinions. ∗Financial support from the NSF under grant SES–0647867 is gratefully acknowledged. Thank you to Matthew Elliott, Carlos Lever, and Yves Zenou for comments on earlier drafts. †Department of Economics, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305, USA. http://www.stanford.edu/∼jacksonm e-mail: [email protected] ‡Edited by Jess Benhabib, Alberto Bisin, and Matthew O. Jackson, forthcoming, Elsevier Press. 1 They also serve as channels for informal insurance and risk sharing, and network structure influences patterns of decisions regarding education, career, hobbies, criminal activity, and even participation in micro-finance. -

Network Effects, Trade, and Productivity

Preprint, forthcoming on Managerial and Decision Economics ∗ Network Effects, Trade, and Productivity Tianle Song† and Susheng Wang‡ April, 2019 Abstract: We consider network effects in the monopolistically competitive model of trade devel- oped by Melitz and Ottaviano (2008). We show that a larger network effect intensifies competition by allowing more productive firms to raise prices and earn higher profits, but forcing less productive firms to reduce prices and earn lower profits. As a result, low productivity firms are driven out of the market. We also show that when network effects are asymmetric, it may be difficult for firms from a country with a small network effect to compete with firms from a country with a large network effect. Keywords: network effects, heterogeneous firms, international trade, productivity JEL classification: F10, F12 ∗ We thank the editor and an anonymous referee for their constructive and insightful feedback. † Corresponding author. Institute for Social and Economic Research, Nanjing Audit University. Email: tsong @connect.ust.hk. ‡ Department of Economics, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Email: [email protected]. 1. Introduction A network effect is a positive effect that arises when the value of a product or service to a user in- creases with the total number of users. Many products, especially telecommunication products and consumer electronics, feature network effects. As an example, the consumer utility of using a tele- phone increases directly with the size of the communication network. Consumer benefits can also depend indirectly on the size of the network. For instance, the users of Macintosh computers are better off when there are more users, because the increased demand may lead to a greater variety of Macintosh software (Church et al. -

Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: a Tale of Two Systems

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Faculty Publications 2010 Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems Alan G. Stavitsky University of Oregon Michael Huntsberger Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Linfield Citation Stavitsky, Alan G. and Huntsberger, Michael, "Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems" (2010). Faculty Publications. Accepted Version. Submission 2. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/mscmfac_pubs/2 This Accepted Version is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Accepted Version must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. [1] Chapter Six Digital Radio Strategies in the United States: A Tale of Two Systems Alan G. Stavitsky Michael W. Huntsberger The case of digital radio in North America illuminates the contradiction between federal communication policy ideals and realpolitik . The policy of the United States government gives official imprimatur to robust competition and to local broadcasting that serves ‘the public interest, convenience or necessity,’ in the words of the federal licensing standard (Radio Act of 1927). In the decades since the passage of the Federal Radio Act, notions of capitalism and communication have intertwined as they have been set down in the re- conceptions and revisions of the original statute. -

Fcc and Am Stereo: a Deregulatory Breach of Duty

THE FCC AND AM STEREO: A DEREGULATORY BREACH OF DUTY JASON B. MEYERt The trend toward governmental deregulation of private enterprise, which began in earnest in the 1970's1 and has gathered momentum under the Reagan administration, has had a significant effect on the telecommunications industry. The Federal Communications Commis- sion (FCC) has reduced regulation of operation and maintenance log- ging2 and eliminated minimum aural transmission power require- ments.' Similarly, a major effort has been made in Congress to enact a bill deregulating broadcast programming.4 In 1984 the FCC justified eliminating or relaxing many licensing requirements on the grounds that such "actions further the Commission's goals of creating, to the maximum extent possible, an unregulated, competitive environment for t A.B. 1980, Princeton University; J.D. Candidate, 1985, University of Pennsylva- nia. The author wrote this Comment while a student at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I See, e.g., Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, Pub. L. No. 96-221, 94 Stat. 132 (codified at scattered sections of Titles 12, 15, 22 & 42 of the U.S.C.) (reducing regulatory control of banks); Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-504, 92 Stat. 1705 (codified at 49 U.S.C. §§ 1300-02, 1305-08, 1324, 1341, 1371-79, 1382, 1384, 1386, 1389, 1461, 1482, 1486, 1490, 1504, 1551-52) (reducing regulatory control of airlines). I See Operating and Maintenance Logs for Broadcast and Broadcast Auxiliary Stations, 48 Fed. Reg. 38,473 (1983). ' The Commission abolished minimum aural power requirements that had previ- ously created a situation in which a station's aural range well exceeded its visual range. -

The Influence of Network Effect on the Valuation of Online Networking

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses 2015 The nflueI nce of Network Effect on the Valuation of Online Networking Companies Yi Xu Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Recommended Citation Xu, Yi, "The nflueI nce of Network Effect on the Valuation of Online Networking Companies" (2015). Honors Theses. 313. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/313 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. II Acknowledgements It is my proud privilege to express my gratitude to Prof. Janet Knoedler, Prof. Gregory Krohn, and Prof. Christopher Magee, who provided substantial help on designing, structuring, and conducting this research project. I am extremely thankful to Prof. Sharon Garthwaite and Prof. Karl Voss for their advice on the mathematical models. I also thank Sarah Decker and Cameron Norsworthy for their help on reading and initial editing of the thesis. III Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter 2 Literature Review ………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Chapter 3 Theoretical Model ………………………………………………………………………….. 12 Chapter 4 Empirical Model .………………………………………………….…………………………. 28 Chapter 5 Empirical Result ……………………………………………………….…………………….. 37 Chapter 6 Conclusion ..…………………………………………………………………………………….. 45 IV List of Tables Chapter 4 Empirical Models 1) Table of Key Variables…………………………………………………………………………… 32 Chapter 5 Empirical Result 2) Regression Result for Group 1 Models…………………………………………………...... 37 3) Regression Result for Group 2 Models…………………………………………………….. 39 V List of Figures Chapter 2 Literature Review Figure 1.