Shakespearean Romanticism and Curricular Genderpellation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

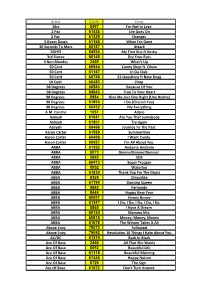

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Demi-Goddess XCLUSIVE What Makes Demi an LGBTQA+ Icon?

guide ® whatson.guide Issue 351Pink Pink 2020 Skye Sweetnam Demi Lovato whatsOn Quiz Stonewall WIN Prizes + FREE Year Planner + LGBTQA+ Special Demi-Goddess XCLUSIVE What makes Demi an LGBTQA+ icon? 01 XCLUSIVEON 005 Agenda> NewsOn 007 Live> Nugen 009 FashOn> LGBTQA+ 011 Issue> 5 Ways 013 Interview> Skye Sweetnam 015 Report> Stonewall 017 Xclusive> Demi Lovato 02 WHATSON 019 Best Of> 2019 Reviews 023 Annual> Jan & Feb 025 Annual> March & April 027 Annual> May & June 029 Annual> July & Aug 031 Annual> Sept & Oct 033 Annual> Nov & Dec 03 GUIDEON 037 Best Picks> Briefing LIL NAS X Jobs Since coming out as gay 053 Classified> last year, 20-year-old 063 SceneOn> Reviews Montero Lamar Hill, known as Lil Nas X, has continued 065 Take10> LGBT Workplace to challenge perceptions of rap and hip hop stars. He’s 066 WinOn> PlayOn broken the record-books, scoring the longest-running number 1 in American chart history, and is up for 6 Grammys. Ads> T +44(0)121 655 1122 [email protected] Editorial> [email protected] About> WhatsOn: Progressive global local guide. Values> Diversity, Equality, Participation, Solidarity. Team WhatsOn> Managing Director Sam Alim Creative Director Setsu Adachi Assistant Editor Judith Hawkins Editorial Assistants Juthy Saha, Puza Snigdha, Dipto Paul Interns Shayan Shakir, George Biggs Books Editor Naomi Round Clubs Editor Nicole Lowe Film Editor Mark Goddard Music Editor Gary Trueman TV Mar Martínez Graphic Designer Promod Chakma, Rashed Hassan UX Designer Suvro Khan IT & Web Fazleh Rabbee, Laila Arzuman Communications -

Starting October 13Th - Jazz Wednesdays Oct

Downtown student assualted 3 I Take your vitamins 9 I Music 18 'PROJECTOR 11,331,101111E rrc s ulen newslale Vribate enu Members ;nests Welcome! • Can apply for membership at t door Starting October 13th - Jazz Wednesdays Oct. 13th - Papa Mambo * Oct. nth - Jazzy Joe and the Alls ars 2 THE PROJECTOR I OCTOBER 11,2004 :PROJECTOR Bookstores face backups BY RHIANNON LEIER bookstore. receipt of the book order," said Editor-in-Chief Coordinator for electronic Olson. Shannon Martin ith only a few weeks technology program, Bryan Another reason for the prob- [email protected] to go until midterms, Crandell, admitted that the rea- lems at the bookstore is that it's W many students don't son the students in his program the first year both stores have have all the books they require don't have all the books they need been running together. News Editor because the Keith Penhall Alana Pona bookstores are [email protected] currently out of a first-year busi- stock. ness administra- The lack of tion coordinator, Entertainment Editor books is appar- who has dealt with Ryan Hladun ent at both the missing books in [email protected] Notre Dame and his faculty, explains Princess Street that the centralized ordering for both Layout/Photo Editor campuses, but locations causes Trevor Kuna most evident at problems. [email protected] the Princess Street location. "If logistics go Pat Hiatt, a awry it is very Layout/Photo Editor sales person noticeable. It hap- Lindsay Winter at the Princess pened in this case," [email protected] Street bookstore said Penhall. -

Exclusive: A&F's New Ruehl

SOUNDS OF STYLE, A SPECIAL REPORT/SECTION II WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • September 2, 2004 • $2.00 Sportswear A knit display in A&F’s latest format, Ruehl. Exclusive: A&F’s New Ruehl By David Moin informally more like a big man on campus than the NEW ALBANY, OHIO — The chairman wears jeans and flip- company chieftain, the approach to brand-building is flops to work and his 650 associates follow suit at the anything but casual. The intensity is as evident as sprawling, campus-style Abercrombie & Fitch ever with A&F’s latest retail brand and its Teutonic- headquarters here. sounding name, Ruehl. That’s just the veneer, though, because for Michael And Ruehl is just the first of three new retail Jeffries and the youthful army of workers he greets See New, Page 4 PHOTO BY DAVID TURNER DAVID PHOTO BY 2 WWD, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Hilton Launches Jewelry With Amazon Sportswear By Marc Karimzadeh GENERAL Paris Hilton in A&F ceo Michael Jeffries lays out the strategy for Ruehl, the firm’s latest chain “It’s just being a girl; every girl NEW YORK — her multicross aimed at post-college shoppers, set to open Saturday in Tampa, Fla. loves jewelry.” necklace. 1 It’s as simple as that for Paris Hilton, who on U.S. textile groups fired up the pressure on the Bush administration, saying Wednesday launched the Paris Hilton Collection of 2 they will file dozens of petitions to reimpose quotas on Chinese imports. jewelry in an exclusive agreement with Amazon.com. -

Musica Straniera

MUSICA STRANIERA AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE 4 Hero Two pages Reinterpretations MSS/CD FOU 4 Non Blondes <gruppo musicale>Bigger, better, faster, more! MSS/CD FOU 50 Cent Get Rich Or Die Tryin' MSS/CD FIF AA.VV. Musica coelestis MSS/CD MUS AA.VV. Rotterdam Hardcore MSS/CD ROT AA.VV. Rotterdam Hardcore MSS/CD ROT AA.VV. Febbraio 2001 MSS/CD FEB AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: agosto 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: aprile 2004 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. Tendenza Compilation MSS/CD TEN AA.VV. Mixage MSS/CD MIX AA.VV. Hits on five 3 MSS/CD HIT AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: ottobre 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. \The \\Brain storm selection MSS/CD BRA AA.VV. Solitaire gold MSS/CD SOL AA.VV. Casual love MSS/CD CAS AA.VV. Oh la la la MSS/CD OHL AA.VV. \The \\magic dance compilation MSS/CD MAG AA.VV. Balla la vita, baby vol. 2 MSS/CD BAL AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: dicembre 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. Harder they come. Soundtrack (The) MSS/CD HAR AA.VV. Cajun Dance Party MSS/CD CAJ AA.VV. \Les \\chansons de Paris MSS/CD CHA AA.VV. \The \\look of love : the Burt Bacharach collection MSS/CD LOO AA.VV. \Le \\canzoni del secolo : 7 MSS/CD CAN AA.VV. Burning heart CD1 MSS/CD BUR AA.VV. \The \\High spirits: spirituals dei neri d'America MSS/CD HIG AA.VV. Dark star rising MSS/CD DAR AA.VV. Merry Christmas from Motown MSS/CD MER AA.VV. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

(This Is) a Song for the Lonely

#1 - Nelly #1 Crush - Garbage (take Me Home) Country Roads - Toots And The Maytals (this Is) A Song For The Lonely - Cher (without You) What Do I Do With Me - Tanya Tucker 1 2 Step - Ciara Feat Missy Elliott 1 4 - Feist 1 Thing - Amerie 10,000 Nights - Alphabeat 100 Percent Chance Of Rain - Gary Morris 100 Years - Five For Fighting 1000 Miles - Vanessa Carlton 123 - Gloria Estefan 1-2-3-4 Sumpin' New - Coolio 18 & Life - Skid Row 19 And Crazy - Bomshel 19-2000 - Gorillaz 1973 - James Blunt 1973(radio Version) - James Blunt 1979 - Smashing Pumpkins 1982 - Randy Travis 1985 - Bowling For Soup 1999 - Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown - Rolling Stones 2 Become 1 - Spice Girls, The 2 Faced - Louise 2 Hearts - Kylie Minogue 21 Guns - Green Day 21 Questions - 50 Cent 24 Hours F - Next Of Kin 2-4-6-8 Motorway - Tom Robinson Band 25 Miles - Edwin Starr 25 Or 6 To 4 - Chicago 29 Nights - Danni Leigh 3 Am - Matchbox Twenty 33 (Thirty-Three) - Smashing Pumpkins 4 In The Morning - Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes - Madonna And Justin Timberlake 4 P.m. - Sukiyaki 4 Seasons Of Loneliness - Boyz Ii Men 45 - Shinedown 4ever - Veronicas, The 5 6 7 8 - Steps 5 Colours In Her Hair - Mcfly 50 50 - Lemar 500 Miles - Peter Paul And Mary 500 Miles Away From Home - Bobby Bare 5-4-3-2-1 - Manfred Mann 59th Street Bridge Song - Simon And Garfunkel 6 Soulsville U.s.a - Wilson Pickett 7 - Prince And The New Power Generation 7 Days - Craig David 7 Rooms Of Gloom - Four Tops 7 Ways - Abs 74-75 - Connells 800 Pound Jesus - Sawyer Brown 8th World Wonder - Kimberly Locke 9 To 5 - Dolly -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2004 5,000+ Top Sellers

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2004 5,000+ TOP SELLERS COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, Videos, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2004 5,000+ titles listing are all of U.K. manufactured (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. 695 10,000 MANIACS campfire songs Double B9 14.00 713 ALARM in the poppy fields X4 12.00 793 ASHER D. street sibling X2 12.80 866 10,000 MANIACS time capsule DVD X1 13.70 859 ALARM live in the poppy fields CD/DVD X1 13.70 803 ASIA aqua *** A5 7.50 874 12 STONES potters field B2 10.50 707 ALARM raw E8 7.50 776 ASIA arena *** A5 7.50 891 13 SENSES the invitation B2 10.50 706 ALARM standards E8 7.50 819 ASIA aria A5 7.50 795 13 th FLOOR ELEVATORS bull of the woods A5 7.50 731 ALARM, THE eye of the hurricane *** E8 7.50 809 ASIA silent nation R4 13.40 932 13 TH FLOOR ELEVATORS going up-very best of A5 7.50 750 ALARM, THE in the poppyfields X3 -

Karaoke List

Artist Code Song 10cc 8497 I'm Not In Love 2 Pac 61426 Life Goes On 2 Pac 61425 Changes 3 Doors Down 61165 When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars 60147 Attack 3OH!3 84954 My First Kiss ft Kesha 3rd Storee 60145 Dry Your Eyes 4 Non Blondes 2459 What's Up 50 Cent 60944 Candy Shop ft. Olivia 50 Cent 61147 In Da Club 50 Cent 60748 21 Questions ft Nate Dogg 50 Cent 60483 Pimp 98 Degrees 60543 Because Of You 98 Degrees 84943 True To Your Heart 98 Degrees 8984 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 61890 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 60332 My Everything A.M. Canche 1051 Adoro Aaliyah 61681 Are You That Somebody Aaliyah 61801 Try Again Aaliyah 60468 Journey To The Past Aaron Carter 61588 Summertime Aaron Carter 60458 I Want Candy Aaron Carter 60557 I'm All About You ABBA 61352 Andante Andante ABBA 8073 Gimme!Gimme!Gimme! ABBA 2692 SOS ABBA 60413 Super Trooper ABBA 8952 Waterloo ABBA 61830 Thank You For The Music ABBA 8369 Chiquitita ABBA 61199 Dancing Queen ABBA 8842 Fernando ABBA 8444 Happy New Year ABBA 60001 Honey Honey ABBA 61347 I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do ABBA 8865 I Have A Dream ABBA 60134 Mamma Mia ABBA 60818 Money, Money, Money ABBA 61678 The Winner Takes It All Above Envy 79073 Followed Above Envy 79092 Revolution 10 Things I Hate About You AC/DC 61319 Back In Black Ace Of Base 2466 All That She Wants Ace Of Base 8592 Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 61118 Beautiful Morning Ace Of Base 61346 Happy Nation Ace Of Base 8729 The Sign Ace Of Base 61672 Don't Turn Around Acid House Kings 61904 This Heart Is A Stone Acquiesce 60699 Oasis Adam -

Girlhood and Autonomy in YA Shakespeares Victoria R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Girlhood and Autonomy in YA Shakespeares Victoria R. Farmer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES GIRLHOOD AND AUTONOMY IN YA SHAKESPEARES By VICTORIA R. FARMER A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2014 Victoria R. Farmer defended this dissertation on October 27, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Celia R. Caputi Daileader Professor Directing Dissertation Aimée Boutin University Representative A.E.B Coldiron Committee Member Margaret (Meegan) Kennedy Hanson Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Jackie and Rachael Weinell, who inspired the genesis of this project. You give me hope for the future of feminism. And to my three wonderful nieces, Afton, Abby, and Eliza, may you grow up with the courage to tell your own stories in your own words. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to my dissertation committee for their guidance, encouragement, and patience throughout the completion of this project. You have given me an excellent professional example. Thank you to my colleagues at Crown College for their inquiries, prayers, and good wishes during this process. I appreciate you listening to me discuss this over and over for the past three years. -

Copy of CDLIST

CD LIST FOR RICK OBEY'S ENTERTAINMENT SONG ARTIST ALBUM 3:00 AM MATCHBOX 20 PROMO ONLY RADIO 11/97 7 PRINCE THE HITS 1 19 PAUL HARDCASTLE ROCK OF THE 80'S 24 JEM PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT MARCH 2005 360 JOSH HOGE PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT JULY 2006 409 THE BEACH BOYS GREATEST HITS 1963 NEW ORDER SUBSTANCE DISC 2 1979 SMASHING PUMPKINS PROMO ONLY CLUB 4/96 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT JULY 2004 1999 PRINCE DJ TOOLS VOLUME 7 1999 PRINCE THE HITS 1 1999 PRINCE PROMO ONLY-CLUB-DEC. '98 TITO PUENTE JR & THE LATIN ( ACCAPELLA) RHYTHM ETHNIC-OYE COMO VA MORE THAN A FEELING BOSTON SWINGIN SINGLES #1 NELLY COLD PROMO ONLY-RADIO-OCT. 2001 $250 A HEAD ALAN SILVESTRI SOUND TRACK- FATHER OF THE BRIDE LUTHER VANDROSS & MARIAH ( INSTRUMENTAL) CAREY ENDLESS LOVE (BABY) HULLY GULLY THE OLYMPICS ULTIMATE 50'S PARTY (GOD MUST HAVE SPENT) A LITTLE MORE TIME ON YOU N SYNC PROMO ONLY-RADIO-NOV. 98 (HOT S**T) COUNTRY GRAMMAR NELLY PROMO ONLY-RADIO-AUG. '00 (HOW COULD YOU) BRING HIM HOME EAMON PROMO ONLY RADIO EDIT AUGUST 2006 (I HATE) EVERYTHING ABOUT YOU THREE DAYS GRACE PROMO ONLY RADIO JANUARY 2004 (I JUST) DIED IN YOUR ARMS CUTTING CREW SOUNDS OF THE 80'S (1987) (I KNOW) I'M LOSING YOU UPTOWN GIRLS LOSING YOU (I) GET LOST ERIC CLAPTON PROMO ONLY - CLUB-DEC. '99 (MUCHO MAMBO)SWAY SHAFT PROMO ONLY-CLUB-NOV. '99 (MUNCHO MAMBO) SWAY (RADIO EDIT) SHAFT BURN THE FLOOR (NOT THE)GREATEST RAPPER 1000 CLOWNS PROMO ONLY-RADIO-FEB.