Body Size and Diversity Exemplified by Three Trilobite Clades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of the Diminutive Trilobite Flexicalymene Retrorsa Minuens from the Cincinnatian Series (Upper Ordovician), Cincinnati Region

EVOLUTION & DEVELOPMENT 9:5, 483–498 (2007) Evaluating paedomorphic heterochrony in trilobites: the case of the diminutive trilobite Flexicalymene retrorsa minuens from the Cincinnatian Series (Upper Ordovician), Cincinnati region Brenda R. Hundaa,Ã and Nigel C. Hughesb aCincinnati Museum Center, 1301 Western Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45203, USA bDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA ÃAuthor for correspondence (email: [email protected]) SUMMARY Flexicalymene retrorsa minuens from the upper- rate of progress along a common ontogenetic trajectory with most 3 m of the Waynesville Formation of the Cincinnatian respect to size, coupled with growth cessation at a small size, Series (Upper Ordovician) of North America lived ‘‘sequential’’ progenesis, or non-uniform changes in the rate of approximately 445 Ma and exhibited marked reduction in progress along a shared ontogenetic trajectory with respect to maximum size relative to its stratigraphically subjacent sister size, can also be rejected. Rather, differences between these subspecies, Flexicalymene retrorsa retrorsa. Phylogenetic subspecies are more consistent with localized changes in analysis is consistent with the notion that F. retrorsa retrorsa rates of character development than with a global hetero- was the ancestor of F. retrorsa minuens. F. retrorsa minuens chronic modification of the ancestral ontogeny. The evolution has been claimed to differ from F. retrorsa retrorsa ‘‘in size of F. retrorsa minuens from F. retrorsa retrorsa was largely alone,’’ and thus presents a plausible example of global dominated by modifications of the development of characters paedomorphic evolution in trilobites. Despite strong similarity already evident in the ancestral ontogeny, not by the origin of in the overall form of the two subspecies, F. -

001-012 Primeras Páginas

PUBLICACIONES DEL INSTITUTO GEOLÓGICO Y MINERO DE ESPAÑA Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO. Nº 9 ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH IN ADVANCES planeta tierra Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and Ciencias de la Tierra para la Sociedad D. García-Bellido 9 788478 407590 MINISTERIO MINISTERIO DE CIENCIA DE CIENCIA E INNOVACIÓN E INNOVACIÓN ADVANCES IN TRILOBITE RESEARCH Editors: I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido Instituto Geológico y Minero de España Madrid, 2008 Serie: CUADERNOS DEL MUSEO GEOMINERO, Nº 9 INTERNATIONAL TRILOBITE CONFERENCE (4. 2008. Toledo) Advances in trilobite research: Fourth International Trilobite Conference, Toledo, June,16-24, 2008 / I. Rábano, R. Gozalo and D. García-Bellido, eds.- Madrid: Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, 2008. 448 pgs; ils; 24 cm .- (Cuadernos del Museo Geominero; 9) ISBN 978-84-7840-759-0 1. Fauna trilobites. 2. Congreso. I. Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, ed. II. Rábano,I., ed. III Gozalo, R., ed. IV. García-Bellido, D., ed. 562 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher. References to this volume: It is suggested that either of the following alternatives should be used for future bibliographic references to the whole or part of this volume: Rábano, I., Gozalo, R. and García-Bellido, D. (eds.) 2008. Advances in trilobite research. Cuadernos del Museo Geominero, 9. -

Introduction to the Trilobites: Morphology, Ecology, Macroevolution and More by Michelle M

Introduction to the Trilobites: Morphology, Ecology, Macroevolution and More By Michelle M. Casey1, Perry Kennard2, and Bruce S. Lieberman1, 3 1Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 66045, 2Earth Science Teacher, Southwest Middle School, USD497, and 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045 Middle level laboratory exercise for Earth or General Science; supported provided by National Science Foundation (NSF) grants DEB-1256993 and EF-1206757. Learning Goals and Pedagogy This lab is designed for middle level General Science or Earth Science classes. The learning goals for this lab are the following: 1) to familiarize students with the anatomy and terminology relating to trilobites; 2) to give students experience identifying morphologic structures on real fossil specimens 3) to highlight major events or trends in the evolutionary history and ecology of the Trilobita; and 4) to expose students to the study of macroevolution in the fossil record using trilobites as a case study. Introduction to the Trilobites The Trilobites are an extinct subphylum of the Arthropoda (the most diverse phylum on earth with nearly a million species described). Arthropoda also contains all fossil and living crustaceans, spiders, and insects as well as several other extinct groups. The trilobites were an extremely important and diverse type of marine invertebrates that lived during the Paleozoic Era. They only lived in the oceans but occurred in all types of marine environments, and ranged in size from less than a centimeter to almost a meter across. They were once one of the most successful of all animal groups and in certain fossil deposits, especially in the Cambrian, Ordovician, and Devonian periods, they are extremely abundant. -

Contributions in BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY

MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions In BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 51 November 29, 1982 A Compendium of Fossil Marine Families J. John Sepkoski, Jr. MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM Contributions in BIOLOGY and GEOLOGY Number 51 November 29, 1982 A COMPENDIUM OF FOSSIL MARINE FAMILIES J. JOHN SEPKOSKI, JR. Department of the Geophysical Sciences University of Chicago REVIEWERS FOR THIS PUBLICATION: Robert Gernant, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee David M. Raup, Field Museum of Natural History Frederick R. Schram, San Diego Natural History Museum Peter M. Sheehan, Milwaukee Public Museum ISBN 0-893260-081-9 Milwaukee Public Museum Press Published by the Order of the Board of Trustees CONTENTS Abstract ---- ---------- -- - ----------------------- 2 Introduction -- --- -- ------ - - - ------- - ----------- - - - 2 Compendium ----------------------------- -- ------ 6 Protozoa ----- - ------- - - - -- -- - -------- - ------ - 6 Porifera------------- --- ---------------------- 9 Archaeocyatha -- - ------ - ------ - - -- ---------- - - - - 14 Coelenterata -- - -- --- -- - - -- - - - - -- - -- - -- - - -- -- - -- 17 Platyhelminthes - - -- - - - -- - - -- - -- - -- - -- -- --- - - - - - - 24 Rhynchocoela - ---- - - - - ---- --- ---- - - ----------- - 24 Priapulida ------ ---- - - - - -- - - -- - ------ - -- ------ 24 Nematoda - -- - --- --- -- - -- --- - -- --- ---- -- - - -- -- 24 Mollusca ------------- --- --------------- ------ 24 Sipunculida ---------- --- ------------ ---- -- --- - 46 Echiurida ------ - --- - - - - - --- --- - -- --- - -- - - --- -

The Evolution of Trilobite Body Patterning

ANRV309-EA35-14 ARI 20 March 2007 15:54 The Evolution of Trilobite Body Patterning Nigel C. Hughes Department of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, California 92521; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2007. 35:401–34 Key Words First published online as a Review in Advance on Trilobita, trilobitomorph, segmentation, Cambrian, Ordovician, January 29, 2007 diversification, body plan The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences is online at earth.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: The good fossil record of trilobite exoskeletal anatomy and on- 10.1146/annurev.earth.35.031306.140258 togeny, coupled with information on their nonbiomineralized tis- Copyright c 2007 by Annual Reviews. sues, permits analysis of how the trilobite body was organized and All rights reserved developed, and the various evolutionary modifications of such pat- 0084-6597/07/0530-0401$20.00 terning within the group. In several respects trilobite development and form appears comparable with that which may have charac- terized the ancestor of most or all euarthropods, giving studies of trilobite body organization special relevance in the light of recent advances in the understanding of arthropod evolution and devel- opment. The Cambrian diversification of trilobites displayed mod- Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2007.35:401-434. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org ifications in the patterning of the trunk region comparable with by UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA - RIVERSIDE LIBRARY on 05/02/07. For personal use only. those seen among the closest relatives of Trilobita. In contrast, the Ordovician diversification of trilobites, although contributing greatly to the overall diversity within the clade, did so within a nar- rower range of trunk conditions. -

An Bolaspide Doza, Argentina

Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser udgivet af Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab Bind 32, nr. 11 Mat. Fys. Medd. Dan. Vid. Selsk. 32, no. 11 (1960) DANISH SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATIONS IN ARGENTINA UNDER THE AUSPICES OF FUNDAC1ÖN WILLIAMS, BUENOS AIRES MIDDI AN BOLASPIDE 01 DOZA, ARGENTINA BY CHIU POULSEN København I960 i kommission hos Ejnar Munksgaard CONTENTS Page Page Introduction................................................. 3 Stigmagnostus canotensis (Rusconi). 15 Remarks on the locality, Cerrillo El Soli- Prometeoraspis canotensis n. sp........... 17 tario........................................................... 5 Williamsina cortesi n. sp...................... 19 Descriptions of genera and species .... 5 harringtoni n. sp............. 20 Brachiopoda............................................. 5 mikkelseni n. sp.............. 21 Dicellomus? sp. ind............................... 5 ornata n. sp..................... 22 Mollusca?................................................... 5 Talbotinella communis n. sp................... 24 Orthotheca sp.......................................... 5 leanzai n. sp..................... 25 Trilobita..................................................... 6 rusconii n. sp.................... 27 Agnostus exsulatus n. sp....................... 6 Bolaspidella lucieae n. sp..................... 28 Baltagnostus hospitus n. sp.................. 7 Canotaspis aliéna ................................ 29 — mendozertsis n. sp............ 8 Goycoia tellecheai Rusconi................ 30 CAavagnostus chipiquensis -

Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites from Antarctica

Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites From Antarctica GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 456-D Early and Middle Cambrian Trilobites From Antarctica By ALLISON R. PALMER and COLIN G. GATEHOUSE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE GEOLOGY OF ANTARCTICA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 456-D Bio stratigraphy and regional significance of nine trilobite faunules from Antarctic outcrops and moraines; 28 species representing 21 genera are described UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1972 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 73-190734 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 70 cents (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-2071 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ ________________________ Dl Physical stratigraphy______________________________ D6 I&troduction. _______________________ 1 Regional correlation within Antarctica ________________ 7 Biostratigraphy _____________________ 3 Systematic paleontology._____-_______-____-_-_-----_ 9 Early Cambrian faunules.________ 4 Summary of classification of Antarctic Early and Australaspis magnus faunule_ 4 Chorbusulina wilkesi faunule _ _ 5 Middle Cambrian trilobites. ___________________ 9 Chorbusulina subdita faunule _ _ 5 Agnostida__ _ _________-____-_--____-----__---_ 9 Early Middle Cambrian f aunules __ 5 Redlichiida. __-_--------------------------_---- 12 Xystridura mutilinia faunule- _ 5 Corynexochida._________--________-_-_---_----_ -

(Upper Cambrian, Paibian) Trilobite Faunule in the Central Conasauga River Valley, North Georgia, Usa

Schwimmer.fm Page 31 Monday, June 18, 2012 11:54 AM SOUTHEASTERN GEOLOGY V. 49, No. 1, June 2012, p. 31-41 AN APHELASPIS ZONE (UPPER CAMBRIAN, PAIBIAN) TRILOBITE FAUNULE IN THE CENTRAL CONASAUGA RIVER VALLEY, NORTH GEORGIA, USA DAVID R. SCHWIMMER1 WILLIAM M. MONTANTE2 1Department of Chemistry & Geology Columbus State University, 4225 University Avenue, Columbus, Georgia 31907, USA <[email protected]> 2Marsh & McLennan, Inc., 3560 Lenox Road, Suite 2400, Atlanta, Georgia 30326, USA <[email protected]> ABSTRACT shelf-to-basin break, which is interpreted to be east of the Alabama Promontory and in Middle and Upper Cambrian strata the Tennessee Embayment. The preserva- (Cambrian Series 3 and Furongian) in the tion of abundant aphelaspine specimens by southernmost Appalachians (Tennessee to bioimmuration events may have been the re- Alabama) comprise the Conasauga Forma- sult of mudflows down the shelf-to-basin tion or Group. Heretofore, the youngest re- slope. ported Conasauga beds in the Valley and Ridge Province of Georgia were of the late INTRODUCTION Middle Cambrian (Series 3: Drumian) Bo- laspidella Zone, located on the western state Trilobites and associated biota from Middle boundary in the valley of the Coosa River. Cambrian beds of the Conasauga Formation in Two new localities sited eastward in the Co- northwestern Georgia have been described by nasauga River Valley, yield a diagnostic suite Walcott, 1916a, 1916b; Butts, 1926; Resser, of trilobites from the Upper Cambrian 1938; Palmer, 1962; Schwimmer, 1989; Aphelaspis Zone. Very abundant, Schwimmer and Montante, 2007. These fossils polymeroid trilobites at the primary locality and deposits come from exposures within the are referable to Aphelaspis brachyphasis, valley of the Coosa River, in Floyd County, which is a species known previously in west- Georgia, and adjoining Cherokee County, Ala- ern North America. -

First Record of the Ordovician Fauna in Mila-Kuh, Eastern Alborz, Northern Iran

Estonian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2015, 64, 2, 121–139 doi: 10.3176/earth.2015.22 First record of the Ordovician fauna in Mila-Kuh, eastern Alborz, northern Iran Mohammad-Reza Kebria-ee Zadeha, Mansoureh Ghobadi Pourb, Leonid E. Popovc, Christian Baarsc and Hadi Jahangird a Department of Geology, Payame Noor University, Semnan, Iran; [email protected] b Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, Golestan University, Gorgan 49138-15739, Iran; [email protected] c Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales, Cathays Park, Cardiff CF10 3NP, United Kingdom; [email protected], [email protected] d Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, Ferdowsi University, Azadi Square, Mashhad 91775-1436, Iran; [email protected] Received 12 May 2014, accepted 5 September 2014 Abstract. Restudy of the Cambrian–Ordovician boundary beds, traditionally assigned to the Mila Formation Member 5 in Mila- Kuh, northern Iran, for the first time provides convincing evidence of the Early Ordovician (Tremadocian) age of the uppermost part of the Mila Formation. Two succeeding trilobite assemblages typifying the Asaphellus inflatus–Dactylocephalus and Psilocephalina lubrica associations have been recognized in the uppermost part of the unit. The Tremadocian trilobite fauna of Mila-Kuh shows close similarity to contemporaneous trilobite faunas of South China down to the species level, while affinity to the Tremadocian fauna of Central Iran is low. The trilobite species Dactylocephalus levificatus and brachiopod species -

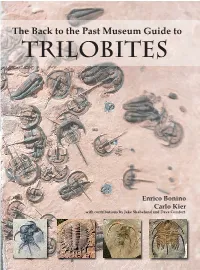

Th TRILO the Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILO BITES

With regard to human interest in fossils, trilobites may rank second only to dinosaurs. Having studied trilobites most of my life, the English version of The Back to the Past Museum Guide to TRILOBITES by Enrico Bonino and Carlo Kier is a pleasant treat. I am captivated by the abundant color images of more than 600 diverse species of trilobites, mostly from the authors’ own collections. Carlo Kier The Back to the Past Museum Guide to Specimens amply represent famous trilobite localities around the world and typify forms from most of the Enrico Bonino Enrico 250-million-year history of trilobites. Numerous specimens are masterpieces of modern professional preparation. Richard A. Robison Professor Emeritus University of Kansas TRILOBITES Enrico Bonino was born in the Province of Bergamo in 1966 and received his degree in Geology from the Depart- ment of Earth Sciences at the University of Genoa. He currently lives in Belgium where he works as a cartographer specialized in the use of satellite imaging and geographic information systems (GIS). His proficiency in the use of digital-image processing, a healthy dose of artistic talent, and a good knowledge of desktop publishing software have provided him with the skills he needed to create graphics, including dozens of posters and illustrations, for all of the displays at the Back to the Past Museum in Cancún. In addition to his passion for trilobites, Enrico is particularly inter- TRILOBITES ested in the life forms that developed during the Precambrian. Carlo Kier was born in Milan in 1961. He holds a degree in law and is currently the director of the Azul Hotel chain. -

An Inventory of Trilobites from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 74. 179 AN INVENTORY OF TRILOBITES FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS MEGAN R. NORR¹, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI1 and JUSTIN S. TWEET2 1National Park Service. 1201 Eye Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20005; -email: [email protected]; 2Tweet Paleo-Consulting. 9149 79th St. S. Cottage Grove. MN 55016; Abstract—Trilobites represent an extinct group of Paleozoic marine invertebrate fossils that have great scientific interest and public appeal. Trilobites exhibit wide taxonomic diversity and are contained within nine orders of the Class Trilobita. A wealth of scientific literature exists regarding trilobites, their morphology, biostratigraphy, indicators of paleoenvironments, behavior, and other research themes. An inventory of National Park Service areas reveals that fossilized remains of trilobites are documented from within at least 33 NPS units, including Death Valley National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Yellowstone National Park, and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. More than 120 trilobite hototype specimens are known from National Park Service areas. INTRODUCTION Of the 262 National Park Service areas identified with paleontological resources, 33 of those units have documented trilobite fossils (Fig. 1). More than 120 holotype specimens of trilobites have been found within National Park Service (NPS) units. Once thriving during the Paleozoic Era (between ~520 and 250 million years ago) and becoming extinct at the end of the Permian Period, trilobites were prone to fossilization due to their hard exoskeletons and the sedimentary marine environments they inhabited. While parks such as Death Valley National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve have reported a great abundance of fossilized trilobites, many other national parks also contain a diverse trilobite fauna. -

Olenid Trilobites: the Oldest Known Chemoautotrophic Symbionts?

Olenid trilobites: The oldest known chemoautotrophic symbionts? Richard Fortey* Department of Paleontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom Communicated by Lynn Margulis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, April 3, 2000 (received for review March 1, 2000) Late Cambrian to early Ordovician trilobites, the family Olenidae, Given the widespread occurrence and taxonomic spread of were tolerant of oxygen-poor, sulfur-rich sea floor conditions, and chemoautotrophic symbiosis, it is likely to have been an ancient a case is made that they were chemoautotrophic symbionts. adaptation. Because direct evidence of the fossil bacteria seldom Olenids were uniquely adapted to this habitat in the Lower preserves, evidence of such habits tends to be inferred from Paleozoic, which was widespread in the Late Cambrian over Scan- taxonomic and͞or morphological data, which is not always dinavia. This life habit explains distinctive aspects of olenid mor- reliable (11). The long-ranging solemyid and lucinid bivalves (10) phology: wide thoraces and large numbers of thoracic segments, indicate that by the Silurian (ca. 420 million years), this life mode thin cuticle and, in some species, degenerate hypostome, and the already had been adopted by some groups with living descen- occasional development of brood pouches. Geochemical and field dants. Ancient vent associations have been recognized from at evidence is consistent with this interpretation. Olenids occupied least the Devonian (12). their specialized habitat for 60 million years until their extinction I show in this paper that even by the late Cambrian period (505 at the end of the Ordovician. million years ago) certain extinct arthropods, trilobites belonging to the family Olenidae, evolved features best understood as evidence olorless sulfur bacteria, a heterogeneous category of bacte- of sulfur chemoautotrophic mode of metabolism.