Raven's Valour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musery Endbericht

Endbericht PG 577: Musikempfehlungen - Automa- tische Erstellung von Playlis- ten zur Entdeckung von Musik Betreuer: Dr. Igor Vatolkin Dr. Geoffray Bonnin Prof. Dr. Dietmar Jannach 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Vorwort5 1.1. Allgemeine Hinweise zur Projektgruppe...................5 1.2. Aufbau des Endberichtes............................5 2. Einführung6 2.1. Wissenschaftlicher Kontext..........................6 2.2. Motivation und Ziele der Projektgruppe...................8 2.2.1. Minimalziele..............................8 2.2.2. Vorgaben für die Projektgruppe....................9 3. Seminarphase 10 3.1. Frontend-Entwicklung - Eine Einführung in JSF2.............. 10 3.2. Playlist Generation............................... 11 3.3. User-Centered Evaluation........................... 12 3.4. Recommender Systems............................. 13 3.5. Metadata Features............................... 14 3.6. High-Level Features.............................. 15 3.7. Similarity Analysis............................... 15 3.8. Emotion Models From Music Theory..................... 16 3.9. Scrum...................................... 16 3.10. MIR Frameworks................................ 17 4. Projektmanagement und Projektplanung 17 4.1. Projektabgrenzung............................... 17 4.1.1. Zeitliche Projektabgrenzung...................... 17 4.1.2. Sachliche Projektabgrenzung..................... 18 4.1.3. Soziale Projektabgrenzung....................... 19 4.2. Weitere Projekttools.............................. 20 5. Aufbau des Projektes und der Infrastruktur -

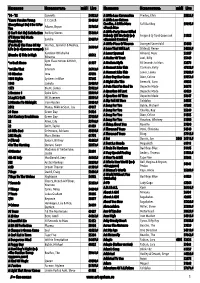

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

After the Burial the Fractal Effect

songcachecache_2017123185012 "Weird Al" Yankovic Shadow of Lucent Moon Hardware Store Slaves of the Plethora Season This Fragile Surface 311 Veil of Illumination Applied Science (Live) Veil of Illumination (2x Bass Pedal) Veil of Illumination (Part 1) (2x Bass Pedal) After The Burial Veil of Illumination (Part 2) (2x Bass Pedal) The Fractal Effect (B) Worst Enemy The Agonist Anika Nilles The Tempest (The Siren's Song Alter Ego AKHT Animals as Leaders B.B. -EVOLUTION- Arithmophobia (B) Backpfeifengesicht (B) Alex Rudinger Brain Dance (2x Bass Pedal) 7 Mindgames (Drum Cover) (2x Bass Pedal) CAFO (2x Bass Pedal) Addictive (Drum Cover) (2x Bass Pedal) Crescent (2x Bass Pedal) Gravity and Friction (Drum Cover) (2x Bass ... Ectogenesis (2x Bass Pedal) Say What You Say (Drum Cover) (2x Bass Pedal) Inner Assassins (Matt Garstka Drum Playthro... Shift (Drum Cover) (2x Bass Pedal) Ka$cade (2x Bass Pedal) Private Visions of the World Alex Skolnick Trio The Woven Web (2x Bass Pedal) Tom Sawyer As Blood Runs Black Alter Bridge Hester Prynne (B) Addicted To Pain (2x Bass Pedal) Blackbird Asuka Sakai, Ado Mizumori Bleed It Dry (2x Bass Pedal) A Crimson Rose and a Gin Tonic Cry A River Cry Of Achilles Babymetal Farther Than The Sun Megitsune (2x Bass Pedal) Fortress Peace Is Broken The Bad Plus The Uninvited Barracuda Andrea Vadrucci (Vadrum) Bad Salad Drum Intro Medley (2x Bass Pedal) Crowded Sky Hungarian Dance (2x Bass Pedal) Crowded Sky (2x Bass Pedal) Infernal Galop (2x Bass Pedal) Deep Roots (2x Bass Pedal) Summer (2x Bass Pedal) Moonlight Super -

AUDIO + VIDEO 8/2/11 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to Be Taken Directly to the Sell Sheet

NEW RELEASES WEA.COM ISSUE 16 AUGUST 2 + AUGUST 9, 2011 LABELS / PARTNERS Atlantic Records Asylum Bad Boy Records Bigger Picture Curb Records Elektra Fueled By Ramen Nonesuch Rhino Records Roadrunner Records Time Life Top Sail Warner Bros. Records Warner Music Latina Word AUDIO + VIDEO 8/2/11 Audio & Video Releases *Click on the Artist Names to be taken directly to the Sell Sheet. Click on the Artist Name in the Order Due Date Sell Sheet to be taken back to the Recap Page Street Date GUCCI MANE & CD- WAKA FLOCKA 1017 Bricksquad WB 528278 FLAME Presents...Ferrari Boyz $18.98 8/2/11 7/13/11 CD- KENNY WAYNE RLP 177232 SHEPHERD BAND How I Go $18.98 8/2/11 7/13/11 CD- KENNY WAYNE RLP 177235 SHEPHERD BAND How I Go (Special Edition) $21.98 8/2/11 7/13/11 A - KENNY WAYNE RRR 177231 SHEPHERD BAND How I Go (Vinyl) $18.98 8/2/11 7/13/11 CD- XIMENA WB 526518 SARINANA Ximena Sariñana $13.99 8/2/11 7/13/11 8/2/11 Late Additions Street Date Order Due Date CD- LAT 528585 Marco di Mauro Marco di Mauro $11.99 8/2/11 7/13/11 Last Update: 07/19/11 ARTIST: Gucci Mane & Waka Flocka Flame TITLE: 1017 Bricksquad Presents...Ferrari Boyz Label: WB/Warner Bros. Config & Selection #: CD 528278 Street Date: 08/09/11 Order Due Date: 07/20/11 UPC: 093624955832 Box Count: 30 AVAILABLE MERCH Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $18.98 Alphabetize Under: G For the latest up to date info on this release visit WEA.com. -

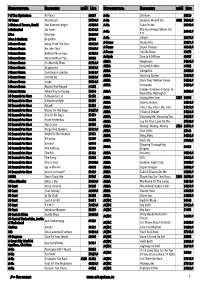

Название Исполнитель Midi Live Название Исполнитель Midi Live

Название Исполнитель midi Live Название Исполнитель midi Live '74 - '75 Connells 54922♫ A Little Less Coversation Presley, Elvis 58822♫ 'Cause You Are Young C.C.Catch 53656♫ A Little Less Sixteen (Everything I Do) I Do It For Candles, A Little More Fall Out Boy 59195♫ Adams, Bryan 53765♫ You «Touch Me» (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 55460♫ A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) (к-ф Fergie & Q-Tip & Goonrock 51958 (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra 59607♫ «Великий Гэтсби») Magdalena (I've Had) The Time Of My Warnes, Jennifer & Medley, A Little Piece Of Heaven Avenged Sevenfold 53880 56930♫ Life (к-ф «Грязные танцы») Bill A Love That Will Last Olstead, Renee 54284♫ Kardinal Offishall & A Lover Spurned Almond, Marc 52387 (Numba 1) Tide Is High 60512 Rihanna A Matter Of Trust Joel, Billy 55449 Gym Class Heroes & Hitch, *ss Back Home 61937 A Modern Myth 30 Seconds to Mars 52876 Neon A Moment Like This Clarkson, Kelly 47158♫ *ss Like That Eminem 56713♫ 10 Minutes Inna 47693 A Moment Like This Lewis, Leona 59382♫ A New Day Has Come Dion, Celine 59753♫ 1001 Nights Systems in Blue 57245 A Night Like This Emerald, Caro 49632 1944 Jamala 59489♫ A Pain That I'm Used To Depeche Mode 56175 1973 Blunt, James 59922♫ A Question Of Lust Depeche Mode 63023 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 58999♫ A Question Of Time Depeche Mode 58647 2 Legit 2 Quit MC Hammer 58991♫ A Sky Full Of Stars Coldplay 54585 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 58454♫ A Song For You Buble, Michael 47208 2012 Manja, Nikki & Sean, Jay 49117 A Song For You Charles, Ray 55249 21 -

Исполнитель Название Midi Live Исполнитель Название Midi Live

Исполнитель Название midi Live Исполнитель Название midi Live ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears 63627 A-Ha Lifelines 58529 10 Years Wasteland 58796♫ A-Ha Summer Moved On 4302 50362♫ 2 Eivissa & Tavare, David Hot Summer Night 45698♫ A-Ha Take On Me 56940♫ The Sun Always Shines On 2 Unlimited No Limit 52121♫ A-Ha 56941♫ 2Pac Changes 56669♫ T.V. 2Pac & Outlawz Breathin 59766 A-Ha Velvet 56377♫ 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 62812♫ A-Teens Mama Mia 53071♫ 3 Doors Down Be Like That 59349♫ A-Teens Super Trouper 46646♫ 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 62725♫ A-Teens Upside Down 43678 3 Doors Down Here Without You 59350 Aaliyah One In A Million 43107 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 62726♫ ABBA Angeleyes 54235♫ 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 59351♫ ABBA As Good As New 61285 3 Doors Down Landing In London 54454♫ ABBA Chiquitita 59187♫ 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 58435♫ ABBA Dancing Queen 53094♫ 3 Doors Down Loser 59534♫ ABBA Does Your Mother Know 54232♫ 3 Doors Down Round And Round 61258 ABBA Fernando 54233♫ Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A 3 Doors Down When You're Young 50614 ABBA 54002♫ Man After Midnight) 30 Seconds to Mars A Beautiful Lie 52152 ABBA Happy New Year 2927 56708 30 Seconds to Mars A Modern Myth 52876 ABBA Honey, Honey 54234♫ 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 52153 ABBA I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do, I Do 54218♫ 30 Seconds to Mars Closer To The Edge 54357♫ ABBA I Have A Dream 54226♫ 30 Seconds to Mars End Of All Days 57479 ABBA Knowing Me, Knowing You 54227♫ 30 Seconds to Mars From Yesterday 46306 ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me 59560♫ 30 Seconds to Mars Hurricane 53655 ABBA Money,