Kathleen Tattersall's Speech

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confirmed Minutes the University of Manchester BOARD OF

Confirmed minutes The University of Manchester BOARD OF GOVERNORS Wednesday, 16 May 2012 Present: Mr Anil Ruia (in the Chair), President and Vice‐Chancellor, Dr Stuart Allan, Mr Stephen Dauncey, Mrs Gillian Easson, Professor Andrew Gibson, Mr Mark Glass, Dame Sue Ion, Mr Paul Lee, Dr Keith Lloyd, Miss Letty Newton, Professor Nancy Papalopulu, Mr Peter Readle, Mr Neville Richardson, Dr Brenda Smith, Professor Chris Taylor, Dr Andrew Walsh, Mr Gerry Yeung (18) In attendance: The Registrar, Secretary and Chief Operating Officer, the Deputy Secretary, the Deputy President and Deputy Vice‐Chancellor, the Director of Human Resources, the Director of Finance, General Counsel, Dr David Barker, Head of Compliance and Risk. The meeting of the Board of Governors was held at Jodrell Bank and preceded by a Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences event. Professor Colin Bailey, Vice‐President and Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, was also in attendance. 1. Declarations of Interest Noted: That the declaration of interest made by the Chair, Mr Anil Ruia, in relation to his role on the HEFCE Board and previously declared in the session, remained relevant to some items on the agenda. A new declaration was also recorded for the Registrar, Secretary and Chief Operating Officer, Will Spinks, who had joined the USS Joint Negotiating Committee as a representative of employers’ members. 2. Minutes Confirmed: The minutes of the meeting held on 8 February 2012. 3. Matters arising from the minutes Received: A report summarising actions consequent on decisions taken by the Board. 4. Summary of business Received: A report, prepared by the Deputy Secretary on the main items of business to be considered at the meeting. -

GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy Specifications and All Exam Boards

Get help and support GCSE Visit our website for information, guidance, support and resources at aqa.org.uk/8464 You can talk directly to the science subject team COMBINED E: [email protected] T: 01483 477 756 SCIENCE: TRILOGY (8464) Specification For teaching from September 2016 onwards For exams in 2018 onwards Version 1.1 04 October 2019 aqa.org.uk Copyright © 2016 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved. AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, schools and colleges registered with AQA are permitted to copy material from this specification for their own internal use. G00571 AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. AQA GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy 8464. GCSE exams June 2018 onwards. Version 1.1 04 October 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Why choose AQA for GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy 5 1.2 Support and resources to help you teach 6 2 Specification at a glance 9 2.1 Subject content 9 2.2 Assessments 9 3 Working scientifically 13 4 Biology subject content 19 4.1 Cell biology 20 4.2 Organisation 26 4.3 Infection and response 34 4.4 Bioenergetics 39 4.5 Homeostasis and response 42 4.6 Inheritance, variation and evolution 49 4.7 Ecology 59 4.8 Key ideas 65 5 Chemistry subject content 67 5.1 Atomic structure and the periodic table 67 5.2 Bonding, structure, and the properties of matter 75 5.3 Quantitative -

Private Candidate Coursework Information Form Candidate

2017 private candidate coursework information form You must complete this form if you are a private candidate entering a modular A-level coursework unit in one of the outgoing specifications, or a Level 1/Level 2 Certificate subject. If you are a private candidate entering controlled assessment, or non-exam assessment for a GCSE, AS or A-level subject you do not need to complete this form, as your centre must authenticate and mark your work. You must complete a separate form for each coursework unit/component. You must give this completed form to the exams officer of your accommodating centre when you make your entry. Exams officers: Please ensure that the appropriate sections have been completed and forward to [email protected] or post to Private Candidates, AQA, Devas Street, Manchester, M15 6EX. 1. Candidate’s personal details (Please use block capitals) Candidate name Candidate no Centre name Centre no Qualification, subject & unit Exam series and Year June 2017 Candidate address postcode telephone no 2. Coursework details Do you wish to ‘carry forward’ your coursework mark from a previous ☐ Yes (go to section 5) ☐ No attempt? (applicable only if you are re-taking the component) 3. Method of study Please one of the following boxes to indicate the method of study you are following: (1) I am a student following a course at an AQA approved centre (eg evening class). The centre will ☐ authenticate and mark* my work alongside and to the same standard as any internal candidates that are being entered. * unless entered for externally-assessed coursework component (2) I am a student studying independently (eg distance learning; private tuition; educated at home) ☐ AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England PCCIF and Wales (number 3644723). -

WHAT IS EDUCATION FOR? Speech by Michael Gove MP to the RSA 30 June 2009

WHAT IS EDUCATION FOR? Speech by Michael Gove MP to the RSA 30 June 2009 INTRODUCTION It’s a pleasure to be here at the Royal Society for the Arts – I am grateful to you Matthew for the kind invitation and appreciate the trouble you’ve taken to provide me with a platform today. I am also appreciative of the work you have done with the RSA since you took over – under your leadership the Society has flourished as never before, and leads debate in social policy, in science policy, and on educational reform. And talking of leadership changes… It is just over two years to the day since Gordon Brown took over as Prime Minister. Many of you I know will have chosen to mark the occasion quietly, in your own way with an appropriate private ceremony. And perhaps Matthew you, and your old boss Tony Blair, were among those of us reflecting on what might have been… And as well as marking the second anniversary of the Prime Minister’s accession, this month also marks the second anniversary of the demise of the old Department of Education and the birth of the Department for Children, Schools and Families. Now names themselves, especially names of Whitehall departments, are far less important than what goes on in their name – Titles, as Lord Mandelson could tell us, are far less important than the substance of policy. But the renaming of the old Department was no idle exercise in empty rebranding – it reflected a philosophical shift in how Government sees its role. -

Obtaining Exam Results

Past exam certificates JMHS does not hold records of students' individual awards nor does it retain any copies of past certificates. To obtain copies of past certificates, you would need to contact the relevant awarding bodies. There are now five main awarding bodies for these qualifications operating in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Please consult the list below to see who may now have a copy of your past certificate: Old Exam Title New Awarding Body Board AEB Associated Examinations AQA (Guildford) Board Tel - Switchboard: 01483 506506 - ask for Candidates Services Records SEG Southern Examining Group Email: [email protected] Fax: 01483 455731 SEREB South East Regional Examinations Board SWExB South Western (Regional) Examinations Board ALSEB Associated Lancashire AQA (Manchester) Schools Examining Board Tel - Exam Records : 0161 953 1180 - ask for Candidates Services Records JMB Joint Matriculation Board Email: [email protected] Fax: 0161 4555 444 NEA Northern Examining Association NEAB Northern Examinations and Assessment Board NREB North Regional Examining Board NWREB North Western Regional Examining Board TWYLREB The West Yorkshire and Lindsey Regional Examinations Board YHREB Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Examinations Board NISEAC Northern Ireland School CCEA Examinations and Assessment Council Download form from the CCEA website , print out and send in hard copy, or NISEC Northern Ireland School Examinations Council Request form - asking for Exam Support - by: Post Tel - Exam Support: 02890 261200 Email: -

Level Physics Specifications and All Exam Boards

Get help and support AS AND Visit our website for information, guidance, support and resources at aqa.org.uk/7408 You can talk directly to the Science subject team A-LEVEL E: [email protected] T: 01483 477 756 PHYSICS AS (7407) A-level (7408) Specifications For teaching from September 2015 onwards For AS exams in May/June 2016 onwards For A-level exams in May/June 2017 onwards Version 1.3 June 2017 aqa.org.uk Copyright © 2015 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved. AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, schools and colleges registered with AQA are permitted to copy material from these specifications for their own internal use. G00486 AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. AS Physics (7407) and A-level Physics (7408). AS exams May/June 2016 onwards. A-level exams May/June 2017 onwards. Version 1.2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Why choose AQA for AS and A-level Physics 5 1.2 Support and resources to help you teach 6 2 Specification at a glance 8 2.1 Subject content 8 2.2 AS 8 2.3 A-level 9 3 Subject content 10 3.1 Measurements and their errors 10 3.2 Particles and radiation 12 3.3 Waves 17 3.4 Mechanics and materials 21 3.5 Electricity 27 3.6 Further mechanics and thermal physics (A-level only) 30 3.7 Fields and their consequences (A-level only) 34 3.8 Nuclear physics (A-level only) 41 3.9 Astrophysics -

Practical Handbook

AS AND A-LEVEL CHEMISTRY AS (7404) A-level (7405) Required practical handbook Version 2.0 This is the Chemistry version of this practical handbook. The sections on tabulating data, significant figures, uncertainties, graphing, and subject specific vocabulary are particularly useful for students and could be printed as a student booklet by schools. The information in this document is correct, to the best of our knowledge as of October 2017. Key There have been a number of changes to how practical work will be assessed in the new A-levels. Some of these have been AQA-specific, but many are by common agreement between all the exam boards and Ofqual. The symbol signifies that all boards have agreed to this. The symbol is used where the information relates to AQA only. AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 2 of 175 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 Practical work in reformed A-level Biology, Chemistry and Physics ............................................. 7 Practical skills assessment in question papers .......................................................................... 12 Guidelines for supporting students in practical work .................................................................. 18 Use of lab books ....................................................................................................................... -

EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Paul Newton, Jo-Anne Baird, Harvey

Prelims:Prelims 12/12/2007 11:05 Page 1 EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION Paul Newton, Jo-Anne Baird, Harvey Goldstein, Helen Patrick and Peter Tymms England operates a qualifications market in which a limited number of providers are accredited to offer curriculum-embedded examinations in many subject areas at a range of levels. The most significant of these qualifications are: • the major 16+ school-leaving examination, the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) • the principal 18+ university selection examination, the General Certificate of Education, Advanced level (A level). Although some examinations are offered by only a single examining board, the majority are offered by more than one. And, although each examination syllabus must conform to general qualifications criteria, and generally also to a common core of subject content, the syllabuses may differ between boards in other respects. A crucial question, therefore, is whether it is easier to pass a particular examination with one board rather than another. In fact, this is just one of many similarly challenging questions that need to be addressed. In recent years, central government has increasingly ensured the regulation of public services and, since 1997, the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA) has been empowered to exercise regulatory authority over the qualifications market in England. One of the ways in which this has been exercised is through commissioning and conducting investigations into comparability, to identify whether a common standard has been applied across -

JCQ Guidance on the Determination of Grades for A/AS Levels and Gcses

JCQInstructions Guidance for on conducting the determination examinations of grades for A/AS Levels and GCSEs for Summer 2021: 1 September 2020 to 31 August 2021 PROCESSES TO BE ADOPTED BY EXAM CENTRES AND SUPPORT AVAILABLEFor the attention FROM of AWARDINGheads of centre, ORGANISATIONS senior leaders within schools and colleges and examination officers Produced on behalf of: UPDATED: 27/07/2021 ©JCQCIC 2020 Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................5 Scope of guidance......................................................................................................................................................................5 Other essential documentation.......................................................................................................................................6 Other relevant documentation.........................................................................................................................................6 Terminology....................................................................................................................................................................................6 What will awarding organisations do?.........................................................................................................................7 What will centres do?...............................................................................................................................................................8 -

AQA Response Reforming Functional Skills Qualifications in English And

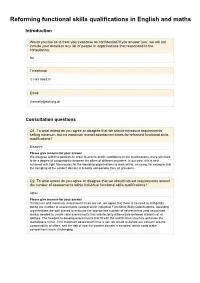

Reforming functional skills qualifications in English and maths Introduction Would you like us to treat your response as confidential?If you answer 'yes', we will not include your details in any list of people or organisations that responded to the consultation. No Telephone 01483 556330 Email [email protected] Consultation questions Q1. To what extent do you agree or disagree that we should introduce requirements setting minimum, but no maximum overall assessment times for reformed functional skills qualifications? Disagree Please give reasons for your answer We disagree with this position. In order to ensure public confidence in the qualifications, there will need to be a degree of comparability between the offers of different providers. In our view, this is best achieved with tight frameworks for the awarding organisations to work within, ensuring, for example, that the sampling of the content domain is broadly comparable from all providers. Q2. To what extent do you agree or disagree that we should not set requirements around the number of assessments within individual functional skills qualifications? Agree Please give reasons for your answer If minimum and maximum assessment times are set, we agree that there is no need to stringently define the number of assessments needed within individual Functional Skills Qualifications. Awarding organisations are well placed to evaluate the appropriate number of assessments (and associated marks) needed to create valid assessments that satisfactorily differentiate between students of all abilities. The freedom to develop assessments that fit with the qualification structure will make the marketplace richer. If no maximum assessment time is set, we would re-iterate our concern around comparability of offers, and the risk of how the content domain is sampled, which could make comparisons more challenging. -

SUBJECT BCCS Link: Art AQA A-Level Art and Design Https

SUBJECT BCCS Link: Art AQA A-Level Art and Design https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/art-and-design/specificat ions/AQA-ART-SP-2015.PDF Biology AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/biology/specifications/A QA-7401-7402-SP-2015.PDF Business Studies WJEC Euqas https://www.eduqas.co.uk/qualifications/business/as-a-level/e duqas-a-business-spec-from-2015.pdf Chemistry AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/chemistry/specifications/ AQA-7404-7405-SP-2015.PDF Drama & TS AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/drama/specifications/AQ A-7262-SP-2016.PDF Economics Edexcel https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev el/economics-a/2015/specification-and-sample-assessment- materials/A_Level_Econ_A_Spec.pdf English Language AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/english/specifications/A QA-7701-7702-SP-2015.PDF English Literature OCR H472 English Literature https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/171200-specification-accredite d-a-level-gce-english-literature-h472.pdf French AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/french/specifications/AQ A-7652-SP-2016.PDF Further Maths AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/mathematics/specificatio ns/AQA-7367-SP-2017.PDF Geography Edexcel: Options are diverse places, https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev coasts, health and human rights el/Geography/2016/specification-and-sample-assessments/P earson-Edexcel-GCE-A-level-Geography-specification-issue- 5-FINAL.pdf German Government & Politics Edexcel - America Path https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev -

The Results Generation

1 The Results Generation Anastasia de Waal and Nicholas Cowen ‘It is an annual ritual for some education commentators to claim that our exam results are evidence of grade inflation and “dumbing down”. This is demoralising for teachers and insulting for students who have worked hard all year.’ Ed Balls, Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families, 3 rd August 2007 i The government has made it clear that it wants its performance in education to be measured through exam performance. In itself, this demand is not necessarily problematic. What is deeply problematic, however, is the fact that the government has also made it clear that it is prepared to go to any lengths, however detrimental to ‘stakeholders’, to achieve the exam performance it is after in the short-term. Limited by flawed long-term education policies, it has resorted to quick-fix strategies to bolster results. Ultimately, the government’s treatment of A-levels has displayed a greater commitment to generating its results than to the students who produce them. This self-serving agenda has become a recurring theme throughout the education system and this is why we have focussed this summer on the disparity between education statistics and learning standards. When concern is voiced, particularly in the case of A-levels, it is quashed as reactionary carping about declining standards from an imaginary ‘golden era’. Critics are positively gagged by accusations of elitism and a devaluing of students’ efforts. It is vital therefore that our aim here is clear: whilst there may be some instances of underlying snobbery from those questioning the value of today’s A-levels, our concern is about the growing chasm between learning and grade production, about protecting students’ interests as opposed to defending the existing, malfunctioning system.