LONDON BOROUGH of LEWISHAM & ORS) Claimants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy Specifications and All Exam Boards

Get help and support GCSE Visit our website for information, guidance, support and resources at aqa.org.uk/8464 You can talk directly to the science subject team COMBINED E: [email protected] T: 01483 477 756 SCIENCE: TRILOGY (8464) Specification For teaching from September 2016 onwards For exams in 2018 onwards Version 1.1 04 October 2019 aqa.org.uk Copyright © 2016 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved. AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, schools and colleges registered with AQA are permitted to copy material from this specification for their own internal use. G00571 AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. AQA GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy 8464. GCSE exams June 2018 onwards. Version 1.1 04 October 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Why choose AQA for GCSE Combined Science: Trilogy 5 1.2 Support and resources to help you teach 6 2 Specification at a glance 9 2.1 Subject content 9 2.2 Assessments 9 3 Working scientifically 13 4 Biology subject content 19 4.1 Cell biology 20 4.2 Organisation 26 4.3 Infection and response 34 4.4 Bioenergetics 39 4.5 Homeostasis and response 42 4.6 Inheritance, variation and evolution 49 4.7 Ecology 59 4.8 Key ideas 65 5 Chemistry subject content 67 5.1 Atomic structure and the periodic table 67 5.2 Bonding, structure, and the properties of matter 75 5.3 Quantitative -

Private Candidate Coursework Information Form Candidate

2017 private candidate coursework information form You must complete this form if you are a private candidate entering a modular A-level coursework unit in one of the outgoing specifications, or a Level 1/Level 2 Certificate subject. If you are a private candidate entering controlled assessment, or non-exam assessment for a GCSE, AS or A-level subject you do not need to complete this form, as your centre must authenticate and mark your work. You must complete a separate form for each coursework unit/component. You must give this completed form to the exams officer of your accommodating centre when you make your entry. Exams officers: Please ensure that the appropriate sections have been completed and forward to [email protected] or post to Private Candidates, AQA, Devas Street, Manchester, M15 6EX. 1. Candidate’s personal details (Please use block capitals) Candidate name Candidate no Centre name Centre no Qualification, subject & unit Exam series and Year June 2017 Candidate address postcode telephone no 2. Coursework details Do you wish to ‘carry forward’ your coursework mark from a previous ☐ Yes (go to section 5) ☐ No attempt? (applicable only if you are re-taking the component) 3. Method of study Please one of the following boxes to indicate the method of study you are following: (1) I am a student following a course at an AQA approved centre (eg evening class). The centre will ☐ authenticate and mark* my work alongside and to the same standard as any internal candidates that are being entered. * unless entered for externally-assessed coursework component (2) I am a student studying independently (eg distance learning; private tuition; educated at home) ☐ AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England PCCIF and Wales (number 3644723). -

Obtaining Exam Results

Past exam certificates JMHS does not hold records of students' individual awards nor does it retain any copies of past certificates. To obtain copies of past certificates, you would need to contact the relevant awarding bodies. There are now five main awarding bodies for these qualifications operating in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Please consult the list below to see who may now have a copy of your past certificate: Old Exam Title New Awarding Body Board AEB Associated Examinations AQA (Guildford) Board Tel - Switchboard: 01483 506506 - ask for Candidates Services Records SEG Southern Examining Group Email: [email protected] Fax: 01483 455731 SEREB South East Regional Examinations Board SWExB South Western (Regional) Examinations Board ALSEB Associated Lancashire AQA (Manchester) Schools Examining Board Tel - Exam Records : 0161 953 1180 - ask for Candidates Services Records JMB Joint Matriculation Board Email: [email protected] Fax: 0161 4555 444 NEA Northern Examining Association NEAB Northern Examinations and Assessment Board NREB North Regional Examining Board NWREB North Western Regional Examining Board TWYLREB The West Yorkshire and Lindsey Regional Examinations Board YHREB Yorkshire and Humberside Regional Examinations Board NISEAC Northern Ireland School CCEA Examinations and Assessment Council Download form from the CCEA website , print out and send in hard copy, or NISEC Northern Ireland School Examinations Council Request form - asking for Exam Support - by: Post Tel - Exam Support: 02890 261200 Email: -

Level Physics Specifications and All Exam Boards

Get help and support AS AND Visit our website for information, guidance, support and resources at aqa.org.uk/7408 You can talk directly to the Science subject team A-LEVEL E: [email protected] T: 01483 477 756 PHYSICS AS (7407) A-level (7408) Specifications For teaching from September 2015 onwards For AS exams in May/June 2016 onwards For A-level exams in May/June 2017 onwards Version 1.3 June 2017 aqa.org.uk Copyright © 2015 AQA and its licensors. All rights reserved. AQA retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, schools and colleges registered with AQA are permitted to copy material from these specifications for their own internal use. G00486 AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (company number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. AS Physics (7407) and A-level Physics (7408). AS exams May/June 2016 onwards. A-level exams May/June 2017 onwards. Version 1.2 Contents 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Why choose AQA for AS and A-level Physics 5 1.2 Support and resources to help you teach 6 2 Specification at a glance 8 2.1 Subject content 8 2.2 AS 8 2.3 A-level 9 3 Subject content 10 3.1 Measurements and their errors 10 3.2 Particles and radiation 12 3.3 Waves 17 3.4 Mechanics and materials 21 3.5 Electricity 27 3.6 Further mechanics and thermal physics (A-level only) 30 3.7 Fields and their consequences (A-level only) 34 3.8 Nuclear physics (A-level only) 41 3.9 Astrophysics -

Practical Handbook

AS AND A-LEVEL CHEMISTRY AS (7404) A-level (7405) Required practical handbook Version 2.0 This is the Chemistry version of this practical handbook. The sections on tabulating data, significant figures, uncertainties, graphing, and subject specific vocabulary are particularly useful for students and could be printed as a student booklet by schools. The information in this document is correct, to the best of our knowledge as of October 2017. Key There have been a number of changes to how practical work will be assessed in the new A-levels. Some of these have been AQA-specific, but many are by common agreement between all the exam boards and Ofqual. The symbol signifies that all boards have agreed to this. The symbol is used where the information relates to AQA only. AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 2 of 175 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4 Practical work in reformed A-level Biology, Chemistry and Physics ............................................. 7 Practical skills assessment in question papers .......................................................................... 12 Guidelines for supporting students in practical work .................................................................. 18 Use of lab books ....................................................................................................................... -

JCQ Guidance on the Determination of Grades for A/AS Levels and Gcses

JCQInstructions Guidance for on conducting the determination examinations of grades for A/AS Levels and GCSEs for Summer 2021: 1 September 2020 to 31 August 2021 PROCESSES TO BE ADOPTED BY EXAM CENTRES AND SUPPORT AVAILABLEFor the attention FROM of AWARDINGheads of centre, ORGANISATIONS senior leaders within schools and colleges and examination officers Produced on behalf of: UPDATED: 27/07/2021 ©JCQCIC 2020 Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................5 Scope of guidance......................................................................................................................................................................5 Other essential documentation.......................................................................................................................................6 Other relevant documentation.........................................................................................................................................6 Terminology....................................................................................................................................................................................6 What will awarding organisations do?.........................................................................................................................7 What will centres do?...............................................................................................................................................................8 -

AQA Response Reforming Functional Skills Qualifications in English And

Reforming functional skills qualifications in English and maths Introduction Would you like us to treat your response as confidential?If you answer 'yes', we will not include your details in any list of people or organisations that responded to the consultation. No Telephone 01483 556330 Email [email protected] Consultation questions Q1. To what extent do you agree or disagree that we should introduce requirements setting minimum, but no maximum overall assessment times for reformed functional skills qualifications? Disagree Please give reasons for your answer We disagree with this position. In order to ensure public confidence in the qualifications, there will need to be a degree of comparability between the offers of different providers. In our view, this is best achieved with tight frameworks for the awarding organisations to work within, ensuring, for example, that the sampling of the content domain is broadly comparable from all providers. Q2. To what extent do you agree or disagree that we should not set requirements around the number of assessments within individual functional skills qualifications? Agree Please give reasons for your answer If minimum and maximum assessment times are set, we agree that there is no need to stringently define the number of assessments needed within individual Functional Skills Qualifications. Awarding organisations are well placed to evaluate the appropriate number of assessments (and associated marks) needed to create valid assessments that satisfactorily differentiate between students of all abilities. The freedom to develop assessments that fit with the qualification structure will make the marketplace richer. If no maximum assessment time is set, we would re-iterate our concern around comparability of offers, and the risk of how the content domain is sampled, which could make comparisons more challenging. -

SUBJECT BCCS Link: Art AQA A-Level Art and Design Https

SUBJECT BCCS Link: Art AQA A-Level Art and Design https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/art-and-design/specificat ions/AQA-ART-SP-2015.PDF Biology AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/biology/specifications/A QA-7401-7402-SP-2015.PDF Business Studies WJEC Euqas https://www.eduqas.co.uk/qualifications/business/as-a-level/e duqas-a-business-spec-from-2015.pdf Chemistry AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/chemistry/specifications/ AQA-7404-7405-SP-2015.PDF Drama & TS AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/drama/specifications/AQ A-7262-SP-2016.PDF Economics Edexcel https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev el/economics-a/2015/specification-and-sample-assessment- materials/A_Level_Econ_A_Spec.pdf English Language AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/english/specifications/A QA-7701-7702-SP-2015.PDF English Literature OCR H472 English Literature https://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/171200-specification-accredite d-a-level-gce-english-literature-h472.pdf French AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/french/specifications/AQ A-7652-SP-2016.PDF Further Maths AQA https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/mathematics/specificatio ns/AQA-7367-SP-2017.PDF Geography Edexcel: Options are diverse places, https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev coasts, health and human rights el/Geography/2016/specification-and-sample-assessments/P earson-Edexcel-GCE-A-level-Geography-specification-issue- 5-FINAL.pdf German Government & Politics Edexcel - America Path https://qualifications.pearson.com/content/dam/pdf/A%20Lev -

Prepare to Teach Meeting: Pre-Event Booklet

A-level Modern Hebrew Preparing to teach Example questions, responses and mark schemes Published: Summer 2018 Non-confidential AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 2 of 56 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Contents Contents Page Paper 1, Question 2 – summary task 4 Paper 1, Question 5 – translation task 10 Paper 1, Question 6 15 Paper 1, Question 7 22 Paper 2, Question 3.2 28 Paper 2, Question 5.2 32 Paper 3, Question 4 – summary task 37 Paper 3, Question 5 – translation task 45 Paper 3, Question 6 – multi-skill task 50 AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 3 of 56 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Paper 1, Question 2 – summary task AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 4 of 56 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Student response AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 5 of 56 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. Mark scheme AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in 6 of 56 England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. -

Application for Past Exam Results Guidance Notes

Application for past exam results Guidance notes Personal details and identity documentation Current full name and title: the name and title you are currently known by. Your full name at time of exam: the name by which you were entered for the exam(s) by your school or college. If this is different to how you are currently known you will need to provide ID showing each name (please see below). Proof of identity We are unable to release any exam records that we may hold for you without appropriate proof of ID in adherence with the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) and security reasons. You need to provide a copy of your official ID with your application showing your full name and date of birth. This can be a birth certificate, a valid passport or ID card, or driving licence. You must prove your name at the time of sitting the exams. • If your name has changed since you took your exams, you must also send a copy of documentary evidence of this, for example: a marriage certificate (decree absolute if you are divorced) or change of name deed (deed poll). • For transgender cases, please contact [email protected] for further advice. • If you have been entered by your school/college under a different name from your legal name, you must send proof of this, for example an official letter (on a letter head) from your school/college or from an official body (e.g. GP or solicitor) confirming your identity and linking the two names. • If your personal details are incorrect, e.g. -

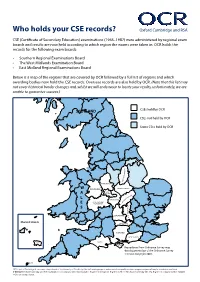

Who Holds Your CSE Records? Oxford Cambridge and RSA

Who holds your CSE records? Oxford Cambridge and RSA CSE (Certificate of Secondary Education) examinations (1965–1987) were administered by regional exam boards and results are now held according to which region the exams were taken in. OCR holds the records for the following exam boards: • Southern Regional Examinations Board • The West Midlands Examination Board • East Midland Regional Examinations Board Below is a map of the regions that are covered by OCR followed by a full list of regions and which awarding bodies now hold the CSE records. Overseas records are also held by OCR. (Note that this list may not cover historical border changes and, whilst we will endeavour to locate your results, unfortunately, we are unable to guarantee success.) SCOTLAND CSEs held by OCR CSEs not held by OCR Some CSEs held by OCR E R I H S M A H G N I T T O N STAFFORDSHIRE W SHROPSHIRE LEICESTERSHIRE WEST A MIDLANDS RE HI NS TO L P M WARWICKSHIRE A H T R HEREFORD AND O E WORCESTER N E R I S H S M A H G N I K OXFORDSHIRE C U B Channel Islands BERKSHIRE Guernsey HAMPSHIRE WEST SUSSEX Jersey DORSET ISLE OF WIGHT Reproduced from Ordnance Survey map data by permission of the Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright 2001. ISLES OF SCILLY OCR is part of Cambridge Assessment, a department of the University of Cambridge. For staff training purposes and as part of our quality assurance programme your call may be recorded or monitored. © OCR 2016 Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. -

AQA March 2014

Exams Officer meetings – spring 2014 The following is an update on the latest developments at JCQ & AQA AQA Information and Updates Entries Some entries for the summer series have been coming in with only partial units, or with only the Subject Award Code. Please note that: o All qualifying units must be entered, with the Subject Award Code, from now on (The 100% rule); o AQA will not be able to retroactively ‘fix’ an entry that comes in with only the Subject Award Code. Speaking and Listening (S&L) assessments from summer 2014 • No longer counts towards final grades but are still reported on certificates alongside the externally assessed grades • Student entries made in the same way as before, with same entry code ENG02 • You will need to submit a mark out of 45 for the S&L assessment • Students without S&L marks will still get their English grades if the entry has been made and not withdrawn. They must also have a valid entry and marks for the written paper and controlled assessment units • Special consideration is not available as S&L is a non-timetabled component • GCSE English and Speaking and Listening FAQs are available on our website at: http://store.aqa.org.uk/pdf/English-Most-FAQ-Booklet.pdf and www.aqa.org.uk/exams-administration/entries/speaking-and-listening AQA Education (AQA) is a registered charity (number 1073334) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales (number 3644723). Our registered address is AQA, Devas Street, Manchester M15 6EX. New script bags • You do not need to complete the box on the front of the bags – this is for examiners to complete.