The Child's Voice: a Closer Look at Pedagogy and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

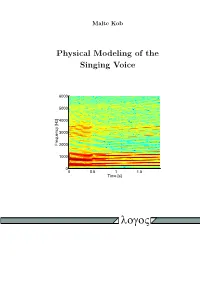

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

Detection and Analysis of Human Emotions Through Voice And

International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology (IJCTT) – Volume 52 Number 1 October 2017 Detection and Analysis of Human Emotions through Voice and Speech Pattern Processing Poorna Banerjee Dasgupta M.Tech Computer Science and Engineering, Nirma Institute of Technology Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Abstract — The ability to modulate vocal sounds high-pitched sound indicates rapid oscillations, and generate speech is one of the features which set whereas, a low-pitched sound corresponds to slower humans apart from other living beings. The human oscillations. Pitch of complex sounds such as speech voice can be characterized by several attributes such and musical notes corresponds to the repetition rate as pitch, timbre, loudness, and vocal tone. It has of periodic or nearly-periodic sounds, or the often been observed that humans express their reciprocal of the time interval between similar emotions by varying different vocal attributes during repeating events in the sound waveform. speech generation. Hence, deduction of human Loudness is a subjective perception of sound emotions through voice and speech analysis has a pressure and can be defined as the attribute of practical plausibility and could potentially be auditory sensation, in terms of which, sounds can be beneficial for improving human conversational and ordered on a scale ranging from quiet to loud [7]. persuasion skills. This paper presents an algorithmic Sound pressure is the local pressure deviation from approach for detection and analysis of human the ambient, average, or equilibrium atmospheric emotions with the help of voice and speech pressure, caused by a sound wave [9]. Sound processing. The proposed approach has been pressure level (SPL) is a logarithmic measure of the developed with the objective of incorporation with effective pressure of a sound relative to a reference futuristic artificial intelligence systems for value and is often measured in units of decibel (dB). -

Consonance & Dissonance

UIUC Physics 406 Acoustical Physics of Music Consonance & Dissonance: Consonance: A combination of two (or more) tones of different frequencies that results in a musically pleasing sound. Why??? Dissonance: A combination of two (or more) tones of different frequencies that results in a musically displeasing sound. Why??? n.b. Perception of sounds is also wired into (different of) our emotional centers!!! Why???/How did this happen??? The Greek scholar Pythagoras discovered & studied the phenomenon of consonance & dissonance, using an instrument called a monochord (see below) – a simple 1-stringed instrument with a movable bridge, dividing the string of length L into two segments, x and L–x. Thus, the two string segments can have any desired ratio, R x/(L–x). (movable) L x x L When the monochord is played, both string segments vibrate simultaneously. Since the two segments of the string have a common tension, T, and the mass per unit length, = M/L is the same on both sides of the string, then the speed of propagation of waves on each of the two segments of the string is the same, v = T/, and therefore on the x-segment of string, the wavelength (of the fundamental) is x = 2x = v/fx and on the (L–x) segment of the string, we have Lx = 2(L–x) = v/fLx. Thus, the two frequencies associated with the two vibrating string segments x and L – x on either side of the movable bridge are: v f x 2x v f Lx 2L x - 1 - Professor Steven Errede, Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois 2002 - 2017. -

Ingressive Phonation in Contemporary Vocal Music, Works by Helmut Lachenmann, Georges Aperghis, Michael Baldwin, and Nicholas

© 2012 Amanda DeBoer Bartlett All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jane Schoonmaker Rodgers, Advisor The use of ingressive phonation (inward singing) in contemporary vocal music is becoming more frequent, yet there is limited research on the physiological demands, risks, and pedagogical requirements of the various ingressive phonation techniques. This paper will discuss ingressive phonation as it is used in contemporary vocal music. The research investigates the ways in which ingressive phonation differs acoustically, physiologically, and aesthetically from typical (egressive) phonation, and explores why and how composers and performers use the various ingressive vocal techniques. Using non-invasive methods, such as electroglottograph waveforms, aerodynamic (pressure, flow, flow resistance) measures, and acoustic analyses of recorded singing, specific data about ingressive phonation were obtained, and various categories of vocal techniques were distinguished. Results are presented for basic vocal exercises and tasks, as well as for specific excerpts from the repertoire, including temA by Helmut Lachenmann and Ursularia by Nicholas DeMaison. The findings of this study were applied to a discussion surrounding pedagogical and aesthetic applications of ingressive phonation in contemporary art music intended for concert performance. Topics of this discussion include physical differences in the production and performance of ingressive phonation, descriptive information regarding the various techniques, as well as notational and practical recommendations for composers. iv This document is dedicated to: my husband, Tom Bartlett my parents, John and Gail DeBoer and my siblings, Mike, Matt, and Leslie DeBoer Thank you for helping me laugh through the process – at times ingressively – and for supporting me endlessly. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I have endless gratitude for my advisor and committee chair, Dr. -

A Review of Related Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 703 SO 025 705 AUTHOR Sipley, Kenneth L. TITLE The Adolescent Female Voice: A Review of Related Literature. PUB DATE Sep 95 NOTE 48p. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; Choral Music; *Females; Fine Arts; Literature Reviews; Music; *Singing; *Vocal Music; Voice Disorders; *Womens Studies ABSTRACT This paper discusses the research findings in voice mutation, vocal instruction, and the application of knowledge to vocal instruction. Much research involves changes in the male aad female adolescent voices, especially of interest to choral directors and music educators. The research defines the vocal development categories as:(1) posture; (2) breath management; (3) relaxation; (4) phonation;(5) resonance; (6) registration; and (7) articulation. A segment on therapy and exercise suggests ways to develop the voice that has been abused. An extensive list of references offers further topics for research. (EH) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OfficemEftm=a1Re.mchamirmovereem EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION v / CENTER (ERIC) "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS is, (his document has been reproducedas MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person or organization originating it. I (,),. 0 Minor changes have been made to 10..014\)`" improve reproduction quality. The Adolescent Female Voice: Points of view or opinions stated in this A review of Related Literature document do not necessarily reprssent officiat OERI position or policy. TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." Introduction This article will present and discuss research findings in voice mutation, vocal instruction, and the application of CD knowledge to vocal instruction.Vocal pedagogues and laryngologists have studied the human voice extensively. -

Analysing and Understanding the Singing Voice

Analysing and Understanding the Singing Voice: Recent Progress and Open Questions Malte Kob, Nathalie Henrich Bernardoni, Hanspeter Herzel, David Howard, Isao Tokuda, Joe Wolfe To cite this version: Malte Kob, Nathalie Henrich Bernardoni, Hanspeter Herzel, David Howard, Isao Tokuda, et al.. Analysing and Understanding the Singing Voice: Recent Progress and Open Questions. Current Bioinformatics, Benthams Science, 2011, 6 (3), pp.1574-8936. 10.2174/157489311796904709. hal- 00618255 HAL Id: hal-00618255 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00618255 Submitted on 22 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 362 Current Bioinformatics, 2011, 6, 362-374 Analysing and Understanding the Singing Voice: Recent Progress and Open Questions Malte Kob*,1, Nathalie Henrich2, Hanspeter Herzel3, David Howard4, Isao Tokuda5 and Joe Wolfe6 1Erich Thienhaus Institute, University of Music Detmold, Germany; 2Department of Speech and Cognition, GIPSA-lab (UMR 5216: CNRS, INPG, University Stendhal, UJF), Grenoble, France; 3Institute for Theoretical Biology, Humboldt- University, Berlin, Germany; 4Department of Electronics, University of York, UK; 5Department of Micro System Technology, Ritsumeikan University, Kusatsu, Japan; 6School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Abstract: The breadth of expression in singing depends on fine control of physiology and acoustics. -

Differentiating Between Human and Electronic Speakers for Voice Interface Security

Hello, Is It Me You’re Looking For? Differentiating Between Human and Electronic Speakers for Voice Interface Security Logan Blue Luis Vargas Patrick Traynor University of Florida University of Florida University of Florida Gainesville, Florida Gainesville, Florida Gainesville, Florida bluel@ufl:edu lfvargas14@ufl:edu traynor@ufl:edu ABSTRACT that report when groceries are low to smart thermostats that can Voice interfaces are increasingly becoming integrated into a variety anticipate desired temperature changes offer great convenience to of Internet of Things (IoT) devices. Such systems can dramatically their users. Given that many of these devices have either limited simplify interactions between users and devices with limited dis- or entirely lack traditional interfaces, an increasing number now plays. Unfortunately, voice interfaces also create new opportunities incorporate voice commands as their primary user interfaces. Voice for exploitation. Specifically, any sound-emitting device within interfaces not only simplify interaction with such devices for tra- range of the system implementing the voice interface (e.g., a smart ditional users, but promote broader inclusion for both the elderly television, an Internet-connected appliance, etc) can potentially and those with disabilities [30]. cause these systems to perform operations against the desires of Voice interfaces also introduce a number of security problems. their owners (e.g., unlock doors, make unauthorized purchases, etc). First, few devices actually authenticate their users. Instead, if a We address this problem by developing a technique to recognize command can be understood by a voice-enabled device, it simply fundamental differences in audio created by humans and electronic executes the request. Any insecure sound-emitting IoT device (e.g., speakers. -

Strobostomp HD for Steel Guitar

peterson Pedal Strobe Tuner for Steel Guitar © 2020 Peterson Electro-Musical Products, Inc. CONTENTS Introduction 3 Registering your Warranty 5 Setting up the StroboStomp HD 5 Connections 6 Pedal Steel Guitar Tuning Options 7 Lap Steel Guitar Tuning Options 7 Dobro®/Resophonic Guitar Tuning Options 7 Tuning with the StroboStomp HD 7 Programming your own Personal Sweetener Settings 8 User Trading Post 10 Connecting the Peterson StroboStomp HD to a Computer 11 New to Pedal Steel Guitar? How to tune to E9th Tuning 12 Peterson Helpdesk 13 Peterson Tuner Range for Steel Guitar 13 Peterson Tuners Online Store 14 2 Strobe Tuners for Pedal Steel, Lap Steel and Resophonic Guitar Steel Guitar Tuning with the Peterson StroboStomp HD Introduction Congratulations on your purchase of the Peterson StroboStomp HD™ tuner pedal! You’ve just bought the most advanced (but simple to use) tuner for pedal steel guitar in the world today; no other pedal tuner has the wealth of steel guitar features found in the Peterson StroboStomp HD. 1.Ultra-accurate detection and highest definition display of any note on a huge color-assignable display. 2.Special Sweetened™ Tuning presets for E9, C6, U12, lap steel and Dobro®/Reso guitars. 3.Programmability – create your own Sweeteners, program up to 128 unique pitches, no limit on notes per octave. 4.Hands-free preset switching. 5.Guaranteed 100% silent, no-pop switching. 6.Choice of 100% True Bypass, Buffered Bypass or Monitor Mode operation. 7.Large easily legible LCD display, visible in direct sunlight or the darkest ambient conditions. 8.User-programmable with the unique ability to program multiple offsets for the same pitch in the same octave. -

Effect of Subglottic Stenosis on Vocal Fold Vibration and Voice Production Using Fluid–Structure–Acoustics Interaction Simulation

applied sciences Article Effect of Subglottic Stenosis on Vocal Fold Vibration and Voice Production Using Fluid–Structure–Acoustics Interaction Simulation Dariush Bodaghi 1, Qian Xue 1 , Xudong Zheng 1,* and Scott Thomson 2 1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04473, USA; [email protected] (D.B.); [email protected] (Q.X.) 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-207-581-2180 Abstract: An in-house 3D fluid–structure–acoustic interaction numerical solver was employed to investigate the effect of subglottic stenosis (SGS) on dynamics of glottal flow, vocal fold vibration and acoustics during voice production. The investigation focused on two SGS properties, including sever- ity defined as the percentage of area reduction and location. The results show that SGS affects voice production only when its severity is beyond a threshold, which is at 75% for the glottal flow rate and acoustics, and at 90% for the vocal fold vibrations. Beyond the threshold, the flow rate, vocal fold vibration amplitude and vocal efficiency decrease rapidly with SGS severity, while the skewness quotient, vibration frequency, signal-to-noise ratio and vocal intensity decrease slightly, and the open quotient increases slightly. Changing the location of SGS shows no effect on the dynamics. Further analysis reveals that the effect of SGS on the dynamics is primarily due to its effect on the flow resistance in the entire airway, which is found to be related to the area ratio of glottis to SGS. Below Citation: Bodaghi, D.; Xue, Q.; the SGS severity of 75%, which corresponds to an area ratio of glottis to SGS of 0.1, changing the SGS Zheng, X.; Thomson, S. -

Instruments of Music Theory

Instruments of Music Theory The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Rehding, Alexander. 2016. "Instruments of Music Theory." Music Theory Online 22, no. 4. Published Version http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.4/mto.16.22.4.rehding.html Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34391750 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUTHOR: Rehding, Alexander TITLE: Instruments of Music Theory KEYWORDS: History of Music Theory, Critical Organology, Sound Studies, Acoustics, Epistemic Thing, Pythagoras, Gaffurius, Vicentino, Cowell, monochord, archicembalo, siren, rhythmicon. ABSTRACT: This article explores musical instruments as a source for the historical study of music theory. The figure of Pythagoras and his alleged penchant for the monochord offers a way into this exploration of the theory-bearing dimensions of instruments. Musicians tend to think of instruments primarily in terms of music-making, but in other contexts instruments are, more broadly, tools. In the context of scientific experimentation, specifically, instruments help researchers come to terms with “epistemic things”—objects under scrutiny that carry specific (but as yet unknown) sources of knowledge within them. Aspects of this experimental practice can productively be transferred to the study of music theory and are explored in a two test cases from different periods of musical theorizing (and instrument building): Nicola Vicentino’s archicembalo from mid-sixteenth century Italy, and Henry Cowell’s rhythmicon from the early-twentieth century America. -

Electroglottographic Analysis of the Voice in Young Male Role of Kunqu Opera

applied sciences Article Electroglottographic Analysis of the Voice in Young Male Role of Kunqu Opera Li Dong 1,* and Jiangping Kong 2 1 School of Humanities, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518060, China 2 Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-1581-182-5016 Abstract: The phonation types used in the young male role in Kunqu Opera were investigated. Two national young male role singers volunteered as the subjects. Each singer performed three voice conditions: singing, stage speech, and reading lyrics. Three electroglottogram parameters, the fundamental frequency, contact quotient, and speed quotient, were analyzed. Electroglottogram parameters were different between voice conditions. Five phonation types were found by clustering analysis in singing and stage speech: (1) breathy voice, (2) high adduction modal voice, (3) modal voice, (4) untrained falsetto, and (5) high adduction falsetto. The proportion of each phonation type was not identical in singing and stage speech. The relationship between phonation type and pitch was multiple to one in the low pitch range, and one to one in the high pitch range. The sound pressure levels were related to the phonation types. Five phonation types, instead of only the two phonation types (modal voice and falsetto) that are identified in traditional Kunqu Opera singing theory, were concomitantly used in the young male role’s artistic voices. These phonation types were more similar to those of the young female roles than to those of the other male roles in the Kunqu Opera. Citation: Dong, L.; Kong, J. Keywords: young male role; singing; stage speech; electroglottography Electroglottographic Analysis of the Voice in Young Male Role of Kunqu Opera. -

The Transformation of the Steel Guitar from Hawaiian Folk Instrument to Popular Music Mainstay

Across the Pacific: The transformation of the steel guitar from Hawaiian folk instrument to popular music mainstay by R. Guy S. Cundell B Mus (Hons.), Grad Dip Ed A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide April 2014 ii Table of Contents I. List of Music Examples ..................................................................................................... v II. Abstract ......................................................................................................................... vii III. Declaration .................................................................................................................. viii IV. Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... ix V. Notes on Transcriptions and Tablature ........................................................................... x Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review ...................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Origins of the Steel Guitar ....................................................................................... 9 1.1 A Mode of Performance .................................................................................................