Patented Electric Guitar Pickups and the Creation of Modern Music Genres Sean M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.2 Humbuckers

5.2 Humbucker 5-9 5.2 Humbuckers The interference occurring with single-coil pickups motivated the development of the Humbucker. Single-coil pickups do not only pickup the vibration of the strings and generate a corresponding electric voltage, but they are also sensitive to magnetic fields as they are radiated by transformers, fluorescent lamps, or mains cables. Instead of having one coil, the "Hum-Bucker" consists of two coils connected to form a dipole and wired such that they are out of phase. The magnetic field generated by external interference sources induces in each coil the same voltage. Because of the anti-phase connection of the two coils the voltages cancel each other out. If the field generated by the permanent magnet would also flow through both coils with the same polarity, the signals generated by the vibrating string also be cancelled – this of course must not happen. For this reason the permanent field flows through the two coils in an anti-parallel manner such that the voltages induced by the vibrating strings are out of phase. Because the coils are connected out of phase, the voltages are turned twice by 180° i.e. they are again in phase (180° +180° = 360° corresp. to 0°). With this arrangement the signal-to-noise ratio can be improved somewhat compared to single-coil pickups (chapter 5.7). As early as the 1930s designers sought to develop a marketable pickup based on compensation principles which were generally already known. Seth Lover, technician with the guitar manufacturer Gibson, achieved the commercial break-through. -

Innovation & Inspiration

Lesson: Innovation & Inspiration: The Technology that Made Electrification Possible Overview In this lesson students learn about technological innovations that enabled the development of the electric guitar. Students place guitar innovations on a timeline of technology and draw conclusions about the relationship between broad technological changes and their impact on music. This lesson builds on the Introduction to the Electric Guitar and borrows concepts from history and science. Ages: High School Estimated Time: up to 35 minutes Objectives: Students will be able to… • Identify significant technological changes that led to the development of the electric guitar. • Analyze the extent to which guitar innovators were influenced by changes in technology. Washington EALRs: • Social Studies: 4.1.1, 4.1.2 • Science: 3.2 Materials Provided by EMP • Electric Guitar Technology Timeline • Guitar Innovations handout Materials Provided by Teacher • N/A Playlist • N/A Procedure 1. Tell students they have three minutes to list as many electrical or digital inventions they use on a daily basis as possible. After time is up, have them share what they came up with and list responses on the board. Choose one or two inventions and ask students to brainstorm all the innovations that made that invention possible. How far can they get? Tell students that today they are going to learn the various innovations that went into the modern electric guitar. (10 minutes) 2. Pass out “Electric Guitar Technology Timeline.” Have students quickly scan the inventions and pick out what inventions are familiar and which are new. Based on this list, can students guess how each invention impacted the development of the electric guitar? (up to 10 minutes) 3. -

Manual V1.0B

An Impact Soundworks Instrument for Kontakt Player 5.7+ Produced by Dimitris Plagiannis User Manual v1.0b CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 INSTALLATION 3 USER INTERFACE 4 PERFORMANCE CONTROLS 5 VOICE MODE 5 ARTICULATION 5 FRET POSITION 6 TONIC 6 VOLUME PEDAL 6 VIBRATO MODE 7 VIBRATO DEPTH 7 AUTO VIBRATO DELAY 7 AUTO VIBRATO ATTACK 7 AUTO VIBRATO RELEASE 7 PREFERENCES 8 RELEASE VOLUME 8 NOISE VOLUME 8 NOISE CHANCE 9 POLY LEGATO THRESHOLD 9 POLY LEGATO PRIORITY 9 SAMPLE OFFSET 9 ROUND ROBIN 10 PITCH BEND RANGE 10 HUMANIZE PITCH 10 HUMANIZE TIMING 10 EXP > VOLUME TABLE 11 VEL > PORTA TABLE 11 VEL > HARM VOL TABLE 12 TEMPERAMENT TABLE 13 HARMONIZATION 13 HARMONY 14 CAPTIONS 14 OPERATION TIPS 14 CREDITS 15 TROUBLESHOOTING 15 COPYRIGHT & LICENSE AGREEMENT 15 OVERVIEW 15 AUTHORIZED USERS 16 A. INDIVIDUAL PURCHASE 16 B. CORPORATE, ACADEMIC, INSTITUTIONAL PURCHASE 16 SCOPE OF LICENSE 16 OWNERSHIP, RESALE, AND TRANSFER 17 INTRODUCTION The pedal steel guitar’s journey to Nashville began in the Hawaiian Islands. Islanders would take an old guitar, lose the frets, raise the strings, and then slide the dull edge of a steel knife to sound wavering chords up and down the strings. Further tinkering led to the invention of the Dobro, the classic bluegrass instrument. The Dobro eventually morphed into the lap steel, which when electrified was one of the first electric guitars, and along with the ukulele became one of the signature sounds of Hawaii. After pedals were added to the lap steel, pedal modifications developed until the standardized pedal steel was born. Unlike the lap steel, the pedal steel guitar is not limited in its voicings – it allows for an unlimited amount of inversions and chords. -

7 Lead Guitar Success Secrets Click Here

7 Lead Guitar Success Secrets Click Here >>> (Video Course) - 7 Lead Guitar Success Secrets - (Video Course) 7 Lead Guitar Success Secrets Disclaimer and Terms of Use: Your reliance upon information and content obtained by you at or through this publication is solely at your own risk. The author assumes no liability or responsibly for damage or injury to you, other persons, or property arising from any use of any product, information, idea, or instruction contained in the content provided to you through this report. This information is intended for individuals taking action to achieve higher musical awareness, and expand their lead guitar vocabulary. However, I can’t be responsible for loss or action to any individual or corporation acting, or not acting, as a result of the material presented here. Reproduction or translation of any part of this work by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, beyond that permitted by the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is unlawful. Much effort has been applied to assure this report is free from errors. These proven lead guitar success secrets are the result of 25 years of lead guitar playing, and teaching. You’re about to learn 7 extremely effective Lead Guitar Success Secrets to quickly ramp up your lead guitar playing. In moments, I'm going to reveal 7 highly important lead guitar success secrets, and you're going to focus upon them quite possibly more than you ever have in all your years of guitar playing. Say goodbye to stale lead guitar playing, and hello to an injection of fresh horsepower. -

ECE313 Music & Engineering Electric Guitars & Basses

ECE313 Music & Engineering Electric Guitars & Basses Tim Hoerning Fall 2014 (last modified 10/13/14) Overview • Electric Guitar • Parts • Electronics • Simulated Circuit • Common styles of Electric guitars • Other electro-mechanical instruments • Pedal Steel • Keyboard Based • Fender Rhodes • Hammond B3 • Hohner Clavinet The Electric Guitar body neck • Main Parts • Body • Wood • Routing • Neck • Fret board • Connection • Bolt on • Set Neck • Neck through Electric Guitar Parts • Physical • Neck • Tuners • Nut (possibly locking) • Fingerboard • Frets (typically 21 – 24) • Fret markers (3,5,7,9,12,15,17 19,21,24) • Wood type • Main Part of neck • Truss rod • Construction (mirrored, skunk stripe, etc) • Body • Bridge • Saddles • Variants • Fixed (Stop tail, tele style) • Whammy bar (standard, 2 point, Floyd Rose, Kahler, Bigsby) • Electronics • Controls • Pickups • Body shape • Single Cutaway • Dual Cutaway • Other Body Pickups Strap Button Bridge (Whammy Bar) Strings Strap Button Pickup Selector Switch Pick Output Guard Jack Coil Split Switch Volume Control Tone Controls Neck String Retainer Tuners & Tuning Pegs Locking Nut Manufacturer and Model Maple Neck Headstock Rosewood Fingerboard Fret Markers Electronics • Electrical • Pickups • Single Coil • Strat • Tele • P90 • Humbucker • 4 wires • Switches • 1 pole 2 throw with bridging • 2 pole 3 throw with and without bridging • 4 pole 5 throw – Super Switch • Pots • Standard Values • 250k, 500k, 1 Meg • Variants • No-Load, Push Pull Pictures of Electronics • Pots • Switches & Jack • Pickups Pickups • The Fundamental guitar pickup is • Source of magnetism North • 1 magnet under 6 ferro- magnetic pole pieces South • 6 magnetic pole pieces • A coil of wire • Usually several thousand turns of wire • The more turns • The hotter the output signal North • The more higher frequency components lost. -

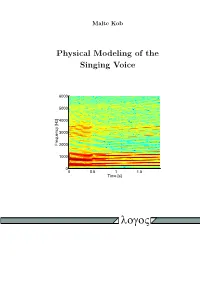

Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice

Malte Kob Physical Modeling of the Singing Voice 6000 5000 4000 3000 Frequency [Hz] 2000 1000 0 0 0.5 1 1.5 Time [s] logoV PHYSICAL MODELING OF THE SINGING VOICE Von der FakulÄat furÄ Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik der Rheinisch-WestfÄalischen Technischen Hochschule Aachen zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER INGENIEURWISSENSCHAFTEN genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Diplom-Ingenieur Malte Kob aus Hamburg Berichter: UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr. rer. nat. Michael VorlÄander UniversitÄatsprofessor Dr.-Ing. Peter Vary Professor Dr.-Ing. JuÄrgen Meyer Tag der muÄndlichen PruÄfung: 18. Juni 2002 Diese Dissertation ist auf den Internetseiten der Hochschulbibliothek online verfuÄgbar. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kob, Malte: Physical modeling of the singing voice / vorgelegt von Malte Kob. - Berlin : Logos-Verl., 2002 Zugl.: Aachen, Techn. Hochsch., Diss., 2002 ISBN 3-89722-997-8 c Copyright Logos Verlag Berlin 2002 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. ISBN 3-89722-997-8 Logos Verlag Berlin Comeniushof, Gubener Str. 47, 10243 Berlin Tel.: +49 030 42 85 10 90 Fax: +49 030 42 85 10 92 INTERNET: http://www.logos-verlag.de ii Meinen Eltern. iii Contents Abstract { Zusammenfassung vii Introduction 1 1 The singer 3 1.1 Voice signal . 4 1.1.1 Harmonic structure . 5 1.1.2 Pitch and amplitude . 6 1.1.3 Harmonics and noise . 7 1.1.4 Choir sound . 8 1.2 Singing styles . 9 1.2.1 Registers . 9 1.2.2 Overtone singing . 10 1.3 Discussion . 11 2 Vocal folds 13 2.1 Biomechanics . 13 2.2 Vocal fold models . 16 2.2.1 Two-mass models . 17 2.2.2 Other models . -

Layout 1 (Page 1)

OWNER’S MANUAL 1550-07 GUS © 2007 Gibson Guitar Corp. To the new Gibson owner: Congratulations on the purchase of your new Gibson electric guitar—the world’s most famous electric guitar from the leader of fretted instruments. Please take a few minutes to acquaint yourself with the information in this booklet regarding materials, electronics, “how to,” care, maintenance, and more about your guitar. And then begin enjoying a lifetime of music with your new Gibson. The Components of the Solidbody Electric Guitar 4 Gibson Innovations 6 The History of Gibson Electric Guitars 8 DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION Body 13 Neck and Headstock 13 Pickups 14 Controls 15 Bridge 17 Tailpiece 18 CARE AND MAINTENANCE Finish 19 Your Guitar on the Road 19 Things to Avoid 20 Strings 21 Install Your Strings Correctly 22 String Gauge 23 Brand of Strings 23 NEW TECHNOLOGY The Gibson Robot Guitar 24 64 Strap Stopbar Tune-o-matic Three-way 12th Fret Button Tailpiece Bridge Pickups Toggle Switch Marker/Inlay Neck Fret Fingerboard Nut Headstock The Components of the Solidbody Electric Guitar Featuring a Les Paul Standard in Heritage Cherry Sunburst Input Jack Tone Volume Binding Body Single Truss Machine Tuning Controls Controls Cutaway Rod Heads Keys Cover 57 Strap Stopbar Tune-o-matic 12th Fret Button Body Tailpiece Bridge Pickups Neck Marker/Inlay Fret Fingerboard Nut Headstock Three-way Toggle Switch The Components of the Solidbody Electric Guitar Featuring a V-Factor Faded in Worn Cherry Input Jack Tone Volume Pickguard Truss Machine Tuning Control Controls Rod Heads Keys Cover 6 Here are just a few of the Gibson innovations that have reshaped the guitar world: 1894 – First archtop guitar 1922 – First ƒ-hole archtop, the L-5 1936 – First professional quality electric guitar, the ES-150 1947 – P-90 single-coil pickup introduced 1948 – First dual-pickup Gibson, the ES-300 1949 – First three-pickup electric, the ES-5 1949 – First hollowbody electric with pointed cutaway, the ES-175 1952 – First Les Paul guitar 1954 – Les Paul Custom and Les Paul Jr. -

Guitar Educator Resource Guide

GUITAR EDUCATOR RESOURCE GUIDE Introduction This guide is intended to assist precollege classroom guitar educators, studio guitar educators, curriculum administrators, and other stakeholders review the curricula, texts, materials, and supplements available and decide which are appropriate for their own students and educational setting. When considering a curriculum, resource, or text, it is important to consider standards in your own locale and district. For national, state, GFA, and professional standards, see the GFA website Education menu >> Education Standards. Contents Quick Reference Comprehensive Guitar Curricula for Classroom Use “Out-of-the-box” methods that include student text, teacher resources/materials, and a sequenced approach to multiple levels. These may also include ensemble and solo repertoire. Classroom Guitar Methods Methods for the classroom that include student text/materials only and/or for a single level General Guitar Methods Methods for general guitar instruction Graded Solo Repertoire Series Sequenced solo repertoire for individual student development. Online Guitar Education Publishers Online/digital publishers with a focus on educational content or application. General Guitar Publishers & Sheet Music Resources General publishers of guitar materials Guitar Educator’s Library Suggestions for reference materials from guitar educators and GFA Certified Schools Teaching Guitar Handbooks Professional Organizations and Professional Development for Guitar Educators Notes - Publisher Descriptions may be redacted for -

Lead Series Guitar Amps

G10, G20, G35FX, G100FX, G120 DSP, G120H DSP, G412A USER’S MANUAL G120H DSP G412A G100FX G120 DSP G10 G20 G35FX LEAD SERIES GUITAR AMPS www.acousticamplification.com IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS Exposure to high noise levels may cause permanent hearing loss. Individuals vary considerably to noise-induced hearing loss but nearly everyone will lose some hearing if exposed to sufficiently intense noise over time. The U.S. Government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has specified the following permissible noise level exposures: DURATION PER DAY (HOURS) 8 6 4 3 2 1 According to OSHA, any exposure in the above permissible limits could result in some hearing loss. Hearing protection SOUND LEVEL (dB) 90 93 95 97 100 103 must be worn when operating this amplification system in order to prevent permanent hearing loss. This symbol is intended to alert the user to the presence of non-insulated “dangerous voltage” within the products enclosure. This symbol is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) instructions in the literature accompanying the unit. Apparatus shall not be exposed to dripping or splashing. Objects filled with liquids, such as vases, shall not be placed on the apparatus. • The apparatus shall not be exposed to dripping or splashing. Objects filled with liquids, such as vases, shall not be placed on the apparatus. L’appareil ne doit pas etreˆ exposé aux écoulements ou aux éclaboussures et aucun objet ne contenant de liquide, tel qu’un vase, ne doit etreˆ placé sur l’objet. • The main plug is used as disconnect device. -

Confusão Entre Viola, Violão E Guitarra. - História Dos Captadores Eletromagnéticos

...e ainda: - Confusão entre Viola, Violão e Guitarra. - História dos captadores eletromagnéticos. … entre outros. Por: João Gravina para Ebora Guitars Ebora Guitars agradece ao Luthier brasileiro João Gravina os textos cedidos, abaixo, para ajudar a entender melhor o mundo da guitarra. O mestre Gravina, pelo que nos é dado a conhecer, é sem dúvida uma voz a ter em conta no mundo da Luthearia pelos anos de prática e conhecimentos adquiridos. … a ele um muito obrigado! Francisco Chinita (Ebora Guitars) O QUE É UMA GUITARRA ELÉTRICA? Tudo começou quando o captador eletromagnético foi criado em 1931, pois antes disso só havia guitarras/violas 100% acústicas. A intenção não era criar um instrumento novo, mas sim aumentar o volume delas num amplificador, para poder tocar guitarra em grupos musicais onde houvesse piano, bateria e metais, ou seja, instrumentos com som muito mais forte. Entretanto, a amplificação acabou conduzindo a uma sonoridade diferente, o que deu na criação de um novo instrumento chamado GUITARRA ELÉTRICA. Só que essa guitarra microfonava muito devido ao seu corpo oco. A busca pelo fim da microfonia é que levou à invenção da guitarra de corpo maciço (solidboby guitar). Esse novo instrumento criado após a Segunda Guerra, a GUITARRA SOLIDBODY, ganhou personalidade própria no início dos anos 50, mudando o curso da História, pois a Música nunca mais foi a mesma a partir daí. Uma das solidbody pioneiras foi a Fender, que dominou pouco a pouco o mercado, devido à sua inteligente postura de marketing. Em poucos anos, seus modelos tornaram-se ícones nas mãos dos ídolos musicais. -

Patented Electric Guitar Pickups and the Creation of Modern Music Genres

2016] 1007 PATENTED ELECTRIC GUITAR PICKUPS AND THE CREATION OF MODERN MUSIC GENRES Sean M. O’Connor* INTRODUCTION The electric guitar is iconic for rock and roll music. And yet, it also played a defining role in the development of many other twentieth-century musical genres. Jump bands, electric blues and country, rockabilly, pop, and, later, soul, funk, rhythm and blues (“R&B”), and fusion, all were cen- tered in many ways around the distinctive, constantly evolving sound of the electric guitar. Add in the electric bass, which operated with an amplifica- tion model similar to that of the electric guitar, and these two new instru- ments created the tonal and stylistic backbone of the vast majority of twen- tieth-century popular music.1 At the heart of why the electric guitar sounds so different from an acoustic guitar (even when amplified by a microphone) is the “pickup”: a curious bit of very early twentieth-century electromagnetic technology.2 Rather than relying on mechanical vibrations in a wire coil to create an analogous (“analog”) electrical energy wave as employed by the micro- phone, “pickups” used nonmechanical “induction” of fluctuating current in a wire coil resulting from the vibration of a metallic object in the coil’s magnetized field.3 This faint, induced electrical signal could then be sent to an amplifier that would turn it into a much more powerful signal: one that could, for example, drive a loudspeaker. For readers unfamiliar with elec- tromagnetic principles, these concepts will be explained further in Part I below. * Boeing International Professor and Chair, Center for Advanced Studies and Research on Inno- vation Policy (CASRIP), University of Washington School of Law (Seattle); Senior Scholar, Center for the Protection of Intellectual Property (CPIP), George Mason University School of Law. -

Detection and Analysis of Human Emotions Through Voice And

International Journal of Computer Trends and Technology (IJCTT) – Volume 52 Number 1 October 2017 Detection and Analysis of Human Emotions through Voice and Speech Pattern Processing Poorna Banerjee Dasgupta M.Tech Computer Science and Engineering, Nirma Institute of Technology Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India Abstract — The ability to modulate vocal sounds high-pitched sound indicates rapid oscillations, and generate speech is one of the features which set whereas, a low-pitched sound corresponds to slower humans apart from other living beings. The human oscillations. Pitch of complex sounds such as speech voice can be characterized by several attributes such and musical notes corresponds to the repetition rate as pitch, timbre, loudness, and vocal tone. It has of periodic or nearly-periodic sounds, or the often been observed that humans express their reciprocal of the time interval between similar emotions by varying different vocal attributes during repeating events in the sound waveform. speech generation. Hence, deduction of human Loudness is a subjective perception of sound emotions through voice and speech analysis has a pressure and can be defined as the attribute of practical plausibility and could potentially be auditory sensation, in terms of which, sounds can be beneficial for improving human conversational and ordered on a scale ranging from quiet to loud [7]. persuasion skills. This paper presents an algorithmic Sound pressure is the local pressure deviation from approach for detection and analysis of human the ambient, average, or equilibrium atmospheric emotions with the help of voice and speech pressure, caused by a sound wave [9]. Sound processing. The proposed approach has been pressure level (SPL) is a logarithmic measure of the developed with the objective of incorporation with effective pressure of a sound relative to a reference futuristic artificial intelligence systems for value and is often measured in units of decibel (dB).