Spire Light 2019 Spire Light: a Journal of Creative Expression Andrew College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joe's Cozy Powell Collection

Joe’s Cozy Powell Collection Cozy POWELL singles Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Belgium}<export 7”, p/s (1), orange lettering> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Belgium}<export blue vinyl 7”, p/s (1), orange / white lettering> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {UK / Denmark}<export 7”, different p/s (2)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Germany}<7”, different p/s (3)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Holland}<7”, different p/s (4)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Holland}<7”, reissue, different p/s (5)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {EEC}<7”, Holland different p/s (6)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Mexico}<7”, different p/s (7)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Spain}<7”, different p/s (8)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Italy}<7”, different p/s (9)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {France}<7”, different p/s (10)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Turkey}<7”, different p/s (11)> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Yugoslavia}<7”, different p/s (12)> Dance With The Drums / And Then There Was Skin {South Africa}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Ireland}<7”> Dance With The Devil [mono] / Dance With The Devil [stereo] {USA}<promo 7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {USA}<7”> Dance With The Devil / And Then There Was Skin {Sweden}<7”> Dance With The -

The Great Gatsby

The Great Gatsby By F. Scott Fitzgerald Download free eBooks of classic literature, books and novels at Planet eBook. Subscribe to our free eBooks blog and email newsletter. Then wear the gold hat, if that will move her; If you can bounce high, bounce for her too, Till she cry ‘Lover, gold-hatted, high-bouncing lover, I must have you!’ —THOMAS PARKE D’INVILLIERS The Great Gatsby Chapter 1 n my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave Ime some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. ‘Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,’ he told me, ‘just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.’ He didn’t say any more but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. In consequence I’m in- clined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores. The abnormal mind is quick to detect and attach itself to this quality when it appears in a normal person, and so it came about that in college I was unjustly accused of being a politician, because I was privy to the secret griefs of wild, unknown men. Most of the con- fidences were unsought—frequently I have feigned sleep, preoccupation, or a hostile levity when I realized by some unmistakable sign that an intimate revelation was quiver- ing on the horizon—for the intimate revelations of young men or at least the terms in which they express them are usually plagiaristic and marred by obvious suppressions. -

Bulfinch's Mythology the Age of Fable by Thomas Bulfinch

1 BULFINCH'S MYTHOLOGY THE AGE OF FABLE BY THOMAS BULFINCH Table of Contents PUBLISHERS' PREFACE ........................................................................................................................... 3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 7 ROMAN DIVINITIES ............................................................................................................................ 16 PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA ............................................................................................................ 18 APOLLO AND DAPHNE--PYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS ............................ 24 JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTO--DIANA AND ACTAEON--LATONA AND THE RUSTICS .................................................................................................................................................... 32 PHAETON .................................................................................................................................................. 41 MIDAS--BAUCIS AND PHILEMON ....................................................................................................... 48 PROSERPINE--GLAUCUS AND SCYLLA ............................................................................................. 53 PYGMALION--DRYOPE-VENUS -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Service Spouse Series

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Service Spouse Series BETTY JANE PEURIFOY (MRS. ARTHUR STEWART) Interviewed by: n/a Initial interview date: n/a TABLE OF CONTENTSS Mrs. Ste art describes her years living in Greece, during the years 1950 to 1953, as the ife of )nited States Ambassador to Greece, John E. Peurifoy. FRAGMENTS OF THE GOLDEN FLEECE A Glorious ,eginning Responsibilities of the ife of the Ambassador Rules of conduct, dress and official protocol Arrival reception in Greece Protocol visits .). S. Envoy/s 0ife Gets Teacup Snub1 2ady Norton/s recent face lift A Royal Gree4 Holiday, ,.C. 6,efore Cyrus7 8isit of Princess Eli9abeth and the Du4e of Edinburgh Royal reception Gree4 Revival Gree4 language study Ne Address: Athens Ambassador/s Residence; 2ydis House Maximos House Moutain in Mauve Mt. Hymettus Her Imperial Highness, the Princess Helen Prince Nicholas of Greece German 00II occupation 1 Peloponnesian Pilgrimage 0ith King and Queen on Royal Yacht 8illage of Malavryta Agia 2avra monastery Gree4AAmerican Affair or Scions of Pericles Gree4s from )nited States Gree4 living customs Affection for )S Island Odyssey 8isit to Dodecanese Patmos, 2eros, Kalymnos and Cos Easter Island in the Hellenes Rhodes, history 2indos Orthodox Easter Kansas Comes to Greece Touring ith relatives Golden Jubilee King Paul/s fiftieth birthday celebrations Distaff Diplomacy Official responsibilities of the Ambassador/s ife Diplomats at 0or4 2ocal charity functions Fleet visits Athens 0or4ing -

Also, a Look at Whitney Houston's New Album

M&M Features Its Year -End Jazz Special. Also, A Look At Whitney Houston's New Album. See Pages 1 0-14 & 9. Europe's Music Radio Newsweekly.Volume 9. Issue 50 .December 12, 1992.3, US$ 5, ECU 4 BPW To Launch Three New Charts Using PhonoNet Data rate and reliable sales data sup- already charted. After battling for by Miranda Watson plied .by PhonoNet will make a changes to the current charts for Separate dance, classical and jazz returnto a sales -only national more than one year, Martinsohn singlessaleschartswillbe chart possible. now worries that some compa- launched in Germany by the end Martinsohn claims the use of nies might give up. "These recent of next year using data compiled airplayweightingputsdance developments are good and I'm byPhonoNet,thecompany companies at a big disadvantage pleased that we've had such open founded by the country's record because the music gets little air- dialogue," he says. "The fact that trade body BPW. PhonoNet has play in Germany, unless it has (continues on page 25) IN THE PICTURE WITH MADONNA - Two lucky winners of a com- been moving closer towards its petition at Italian EHR net Rete 105 were given the chance to meet goal of establishing an electronic Madonna during the her promotion campaign for album "Erotica." The in-store sales monitoring- system event was later followed by a disco in Milan during which the album to replace the old and much -criti- Rush Expected For was previewed. cised questionnaire system. Over 50 stores. are now taking part in the PhonoNet system and testing UK Regional Licence will begin during the first quarter thelargestserviceoutsideof PolyGram Plans of 1993 using 40-60 outlets. -

BIOGRAFIA Queen É Uma Banda De Rock Formada Em Londres

QUEEN BIOGRAFIA Queen é uma banda de rock formada em Londres, Inglaterra, integrada por Freddie Mercury (vocal, falecido), Brian May (guitarra), Roger Taylor (bateria) e John Deacon (baixo). Foi uma das mais populares bandas inglesas dos anos 1970 e 1980, sendo precursora do rock tal como hoje o conhecemos, com magníficas produções dos seus concertos e videoclipes das suas canções. Mesmo nunca tendo sido levada a sério pelos críticos, que consideravam a sua música “comercial”, a banda tornou-se das mais famosas entre o público, graças à sua mistura única entre as complexas e elaboradas apresentações ao vivo e o dinamismo e carisma da sua estrela maior, o vocalista Freddie Mercury. História 1968-1970 Brian May e Roger Taylor tocavam numa banda chamada Smile, com o vocalista/baixista Tim Staffel. Freddie era colega de quarto de Tim e seguia assiduamente os concertos do grupo. A essa altura, Freddie era vocalista de outras bandas, como os Wreckage ou os Ibex. Para além disso, não tinha qualquer problema em partilhar as suas ideias acerca da direção musical que os Smile deviam tomar. Tim decidiu então pôr fim à sua carreira nos Smile e juntou-se a uma banda chamada Humpty Bong. Freddie substituiu-o e o grupo começou à procura de um baixista profissional. O primeiro seria Barry Mitchell; só em 1971 o grupo descobriu John Deacon. Com a formação definida, o quarteto estava definitivamanete em marcha, possuidores de uma imagem inovadora, desfazendo regras musicais anteriores, compondo temas de absoluta originalidade, nada, ou bem pouco a ver com o resto do rock daqueles tempos. -

Rare LP) German MCA VG/VG+ £2 14

2010 LP and CD CATALOGUE WINDMILL RECORDS P.O.BOX 262 SHEFFIELD S1 1FS ENGLAND TEL. 0114 2649185 TEL. 0114 2640135 (If no answer at the above number) FAX. 0114 2530489 EMAIL – [email protected] WEBSITE – www.windmill-records.co.uk THE FOLLOWING CONDITION CODES APPLY. M = MINT (Played Slightly but with no visible signs of being so) EX = EXCELLENT (Played Regularly, but ver well looked after) VG = VERY GOOD (Average Wear, should play and sound OK) G = GOOD (Lots Of Surface Wear) THE FOLLOWING ABBREVIATIONS USED. DH = Drill hole thru label LT = Label Tear WOL = Writing On Label LS = Sticker On Label LM = Label Mark RE = Re- Issue ST = Stereo WOC = Writing On Cover WOBC = Writing on Back Cover POSTAGE AND PACKING (UK) £2.50 for 1st LP then 70p each one after – On large orders Maximum P&P is £7 (UK Only) CDs/DVDs = £1.60 for 1st, then 20p each one after Recorded Delivery (1 to 3 LPs) = 75p Extra Special Delivery = Please Enquire for rates All Records sent with Certificate Of Postage and we cannot accept responsibility For records lost or damaged in the post – If in doubt have your order sent by Special Delivery (Overseas Registered) UK PAYMENT CHEQUES – Please make payable to Windmill Records CASH – Please Send By Special Delivery or at least Recorded Delivery POSTAL ORDERS – Please leave blank as I can use these for refunds CREDIT CARDS – Mastercard/Visa/Maestro/Switch etc PAYPAL OVERSEAS. Please Write,Phone,fax or email your order and we will let you know total including Postage. -

Great Gatsby

Chapter 1 n my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave I me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since. “Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the ad- vantages that you’ve had.” He didn’t say any more, but we’ve always been unusually communicative in a reserved way, and I understood that he meant a great deal more than that. In consequence, I’m in- clined to reserve all judgments, a habit that has opened up many curious natures to me and also made me the victim of not a few veteran bores. The abnormal mind is quick to detect and attach itself to this quality when it appears in a normal person, and so it came about that in college I was unjustly accused of being a politician, because I was privy to the secret griefs of wild, unknown men. Most of the confidences were unsought — frequently I have feigned sleep, preoccupation, or a hostile lev- ity when I realized by some unmistakable sign that an intimate revelation was quivering on the horizon; for the intimate revel- ations of young men, or at least the terms in which they ex- press them, are usually plagiaristic and marred by obvious sup- pressions. Reserving judgments is a matter of infinite hope. I am still a little afraid of missing something if I forget that, as my father snobbishly suggested, and I snobbishly repeat, a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth. -

Yet Another Way of Wiring… the Brian May Wiring System by Quentin Jacquemart with Permission

Yet another way of wiring… The Brian May Wiring System By Quentin Jacquemart with permission Brian May - well known for his superb guitar work in Queen - has one of the most distinctive sound in the world. Back to 1963, when he was 16, unsatisfied with the offers of big guitar manufacturers, and not able to buy one anyway, he decided to build, with the help of his father, his version of the dream guitar… now known as the Red Special (or The Old Lady). The work took 18 months and ended up with Brian’s guitar which he’s used since… and is still using as his main guitar today for both, live and studio. I’m not gonna expand on the built of the guitar and the special materials used for its construction because my point here is to explain the pickup wiring. However, many sites on the net tells you the story. Take a look, it’s worth it! Brian May playing the Red Special. (Freddie Mercury behind). Photo from QueenOnLine.com The guitar was fitted with Burns Tri-Sonics single coil pickups and was wired in series rather than parallel (like on Fenders or Gibsons) with additional phases switches. So now… what is a pickup wired in parallel? If you wire pickups in parallel, that means the output signal of the pickup (whatever you played on your strings) is directly going into the input of the amp, traveling the shortest way possible. And pickups in series? Well, the output of a pickup is going into the input of the next one. -

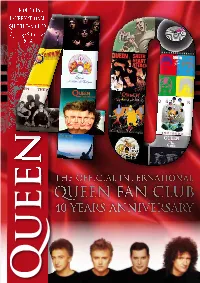

Qfc-Mag-Summer-2014-Print.Pdf

THE OFFICIAL INTERNATIONAL QUEEN FAN CLUB Spring/Summer 2014 Editorial From Queen to You Hi Everyone! „Queen and Adam Lambert have managed to ace the nerve-wracking first night of their tour I hope you are all well and happy wherever you are? Apologies for the delay in this issue - it in North America, rocking Chicago‘s United Center to its foundations with a bombastic rock has been manic in the fan club since the start of the year! When the North American/Canadian show to surpass all others.“ - Contactmusic.com All Pictures: Neal Preston tour was announced, I had about a thousands new members within the space of a week, and I am STILL trying to get them all entered into the database and sent out... then they „The show epitomized Queen, in all its flamboyant glory“ - announced Korea and Japan, then Australia! More new members! But I am not complai- Chicago Tribune. ning, it will ensure the fan club stays alive for a bit longer yet! Big thanks to Jim Jenkins for the fabulous article in this issue about the fan club and our Chicago, June 19, 2014 40 year reign! I am amazed at what we have managed to achieve in those 40 years (I have ‚only‘ done it for 32 of them...!). What a Queen year so far! I have seen footage of the shows - just AWESOME! The iHeart Radio show in Los Angeles on June 16th was quite brilliant - hopefully you have caught that on YouTube by now! Fingers crossed for dates THIS side of the pond in Europe and the UK! Obviously should I hear anything I will make sure you all know about it! Just make sure you are registered on our members website - www.queenmembers.com. -

2007 Ukprogram(5-14-07)

In London Call Toll Free: 0845 094 3256 In London Call Toll Free: 0845 094 3256 Welcome! Dear Rock Stars, Welcome to camp! I'd like to welcome all of you--campers, counselors, veterans, and media—to our first ever Rock 'n Roll Fantasy Camp in London. You are about to embark on an epic journey. This camp promises to be our most amazing yet! For the last 10 years, this camp has been a dream in the making. When I first started this camp, one of my dreams was to be able to give campers access to one of the most famous studios in the world, Abbey Road. Now that dream has been realized and I'm thrilled to bring you inside and let you experience what the Beatles, Pink Floyd, and Green Day have all been a part of. I'm equally excited to have you at John Henry’s. This is the very studio where rock royalty rehearses and records, where bands playing at Live 8 or the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame ceremony come to practice. Many thanks to John Henry for allowing us to use his famous facility. Then we're on to Liverpool! It's an even more special time to visit the city where the Beatles got their start, because it also happens to be the 40th Anniversary of one of the greatest albums of all time, Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Seeing the sights and sounds of Liverpool, and jamming to Beatles songs at the legendary Cavern Club---this year's camp will surely be a once-in-a-lifetime event! It's a week to make all your dreams come true, so turn off your cellphones and get ready. -

Brian May – Back to the Light (Gold Edition)

Brian May – Back To The Light (Gold Edition) (51:13, 2-CD, LP, Digital, Boxset, EMI/Universal, 2021/1992) Für viele Queen-Fans sah es 1992 ganz danach aus, dass Brian May künftig mit seiner Solokarriere ihre Bedürfnisse stillen würde. Wo Roger Taylor mit seinen Soloalben und seiner Zweitband The Cross sämtlich stilistischen Parallelen zu Queen vermieden hatte, John Deacon wenig auf Solo-Aktivitäten aus war und Freddie Mercury nicht mehr unter uns weilte, brachte Brian Mays offizielles Debüt über weite Strecken genau das, was man sich erwartete: breitwändig produzierte Songs voller Pathos, Energie und knackiger Gitarren, die man sich eigentlich allesamt auf einem potenziellen „Innuendo“-Nachfolger vorstellen könnte. Die alte Tante EMI bringt nun eine erweiterte und remasterte Neuauflage des längst rar gewordenen Albums in die Läden. Das Album „Back To The Light“ war im Prinzip das Ergebnis von mindestens zehn Jahren Arbeit. Das eröffnende Instrumental ‚The Dark‘ war beispielsweise ein Outtake des „Flash Gordon“- Soundtracks. ‚Too Much Love Will Kill You‘ war zu „The Miracle“-Zeiten von Queen als Demo aufgenommen, aber letztlich abgelehnt worden, weil May den Song mit zwei Gastautoren geschrieben hatte, was laut Meinung seiner Bandkollegen zu rechtlichem Hickhack hätte führen können. ‚Resurrection‘ und ‚Nothin‘ But Blue‘ waren in instrumentalen Versionen mit anderem Titel bereits auf dem Cozy-Powell-Album „The Drums Are Back“ erschienen, und ‚Let Your Heart Rule Your Head‘ hatte Brian für Skiffle-Legende Lonnie Donegan geschrieben. Dass das Endresultat so stringent und zeitlos klang, dürfte fraglos der Queen-Schule geschuldet sein: wenn jemand Erfahrung damit hatte, Material unterschiedlichster Couleur miteinander zu verbinden, dann die Ex-Queen-Mannschaft.