Vanilla Culture in Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Something Sweet Cupcake Flavor List 2017 Name Description

Something Sweet Cupcake Flavor List 2017 Name Description (Some Flavors May Not Be Available All Year) Abigail Cream Cake, Vanilla Bean frosting, topped with a fondant flower Almond-Raspberry Almond Cake, Raspberry filling, Almond/Raspberry swirled frosting, topped w/sliced almonds Aloha Pineapple Cake, Pineapple frosting, topped with Macadamia nuts and toasted coconut AmaZING Yellow Cake, Vanilla filling, Raspberry frosting - Like a Hostess Zinger Apple Pie Apple Cake, Vanilla/ Cinnamon frosting, topped w/ Caramel sauce and a pie crust wafer Banana Cream Banana Cake, Vanilla frosting, topped w/vanilla wafers Banana Loco Banana Cake, Nutella filling, Chocolate/Nutella swirled frostong topped with yellow jimmies and a banana chip Banana Split Banana Cake, Vanilla frosting, topped w/ caramel, chocolate and strawberry sauce plus a cherry on top Beautifully Bavarian Yellow Cake, Chocolate frosting, Bavarian cream filling Better Than Heath Chocolate Cake, Caramel frosting, topped w/Caramel sauce and Heath toffee bits Birthday Cake Vanilla Cake with sprinkles, Tie-dyed Vanilla frosting, topped w/sprinkles Black Bottom Chocolate Fudge Cake filled and iced with Cream Cheese frosting, edged with black sugar crystals Black Forest Dark Chocolate Cake, Vanilla cream filling, Cherry frosting, cherry on top Blackberry Lemon Lemon Cake with Blackberries, Lemon/Blackberry frosting Blueberry Swirl Blueberry cake, blueberry vanilla frosting Boston Cream Pie Yellow Cake, Cream filling, covered with chocolate ganache Bourbon Pecan Bourban flavored chocolate -

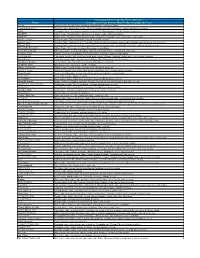

Lista Plantas, Reserva

Lista de Plantas, Reserva, Jardín Botanico de Vallarta - Plant List, Preserve, Vallarta Botanical Garden [2019] P 1 de(of) 5 Familia Nombre Científico Autoridad Hábito IUCN Nativo Invasor Family Scientific Name Authority Habit IUCN Native Invasive 1 ACANTHACEAE Dicliptera monancistra Will. H 2 Henrya insularis Nees ex Benth. H NE Nat. LC 3 Ruellia stemonacanthoides (Oersted) Hemsley H NE Nat. LC 4 Aphelandra madrensis Lindau a NE Nat+EMEX LC 5 Ruellia blechum L. H NE Nat. LC 6 Elytraria imbricata (Vahl) Pers H NE Nat. LC 7 AGAVACEAE Agave rhodacantha Trel. Suc NE Nat+EMEX LC 8 Agave vivipara vivipara L. Suc NE Nat. LC 9 AMARANTHACEAE Iresine nigra Uline & Bray a NE Nat. LC 10 Gomphrena nitida Rothr a NE Nat. LC 11 ANACARDIACEAE Astronium graveolens Jacq. A NE Nat. LC 12 Comocladia macrophylla (Hook. & Arn.) L. Riley A NE Nat. LC 13 Amphipterygium adstringens (Schlecht.) Schiede ex Standl. A NE Nat+EMEX LC 14 ANNONACEAE Oxandra lanceolata (Sw.) Baill. A NE Nat. LC 15 Annona glabra L. A NE Nat. LC 16 ARACEAE Anthurium halmoorei Croat. H ep NE Nat+EMEX LC 17 Philodendron hederaceum K. Koch & Sello V NE Nat. LC 18 Syngonium neglectum Schott V NE Nat+EMEX LC 19 ARALIACEAE Dendropanax arboreus (l.) Decne. & Planchon A NE Nat. LC 20 Oreopanax peltatus Lind. Ex Regel A VU Nat. LC 21 ARECACEAE Chamaedorea pochutlensis Liebm a LC Nat+EMEX LC 22 Cryosophila nana (Kunth) Blume A NT Nat+EJAL LC 23 Attalea cohune Martius A NE Nat. LC 24 ARISTOLOCHIACEAE Aristolochia taliscana Hook. & Aarn. V NE Nat+EMEX LC 25 Aristolochia carterae Pfeifer V NE Nat+EMEX LC 26 ASTERACEAE Ageratum corymbosum Zuccagni ex Pers. -

In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Bixa Orellana (Annatto) Seed Extract

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science Vol. 4 (02), pp. 101-106, February, 2014 Available online at http://www.japsonline.com DOI: 10.7324/JAPS.2014.40216 ISSN 2231-3354 In vitro antioxidant activity of Bixa orellana (Annatto) Seed Extract 1Modupeola Abayomi*, 2Amusa S. Adebayo*, 3Deon Bennett, 4Roy Porter, and 1Janet Shelly-Campbell 1School of Pharmacy, College of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Jamaica, 237 Old Hope Road, Kingston 6. 2Department of Biopharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, Roosevelt University, 1400N Roosevelt Boulevard, Schaumburg, IL 60173, USA. 3Department of Chemistry Faculty of Science and Sports, University of Technology, Jamaica, 237 Old Hope Road, Kingston 6. 4Department of Chemistry, University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston 7, Jamaica. ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Article history: The seeds of Bixa orellana (Annatto, family Bixaceae), have been used in food coloring for over 50 years. With Received on: 03/09/2013 the aim of introducing its extracts as pharmaceutical colorant, there is the need to investigate the biological and Revised on: 05/11/2013 pharmacological activities of the extract. This study was designed to develop extraction protocols for annatto Accepted on: 10/02/2014 coloring fraction with potential for pharmaceutical application and evaluate the antioxidant activity of the Available online: 27/02/2014 extracts in vitro. Powdered seed material was extracted using acid-base protocols and the crystals obtained were washed with deionized water, oven-dried for about 12 hours at 45 °C and stored in air-tight containers. The in Key words: vitro antioxidant activity was tested via 2,2-diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity and In-vitro, Antioxidant, Bixa iron (III) oxide reducing power using ascorbic acid (vitamin C) as a reference standard. -

Use of Natural Colours in the Ice Cream Industry

USE OF NATURAL COLOURS IN THE ICE CREAM INDUSTRY Dr. Juan Mario Sanz Penella Dr. Emanuele Pedrazzini Dr. José García Reverter SECNA NATURAL INGREDIENTS GROUP Definition of ice cream Ice cream is a frozen dessert, a term that includes different types of product that are consumed frozen and that includes sorbets, frozen yogurts, non-dairy frozen desserts and, of course, ice cream. In order to simplify its classification, we can consider for practical purposes two different types of frozen desserts: ice cream and sorbets. Ice cream includes all products that have a neutral pH and contain dairy ingredients. While sorbet refers to products with an acidic pH, made with water and other ingredients such as fruit, but without the use of dairy. Additionally, when referring to ice cream, we are not referring to a single type of product, we are actually referring to a wide range of these. Ice cream is a food in which the three states of matter coexist, namely: water in liquid form and as ice crystals, sugars, fats and proteins in solid form and occluded air bubbles in gaseous form, Figure 1. Artisanal ice creams based on natural ingredients which give it its special texture. It should be noted that ice cream is a very complete food from a nutritional point of view since it incorporates in its formulation a wide range of ingredients (sugars, milk, fruits, egg products ...) essential for a balanced diet. Another aspect of great relevance in the manufacture of ice cream is the hedonic factor. Ice cream is consumed mainly for the pure pleasure of tasting it, the hedonic component being the main factor that triggers its consumption, considering its formulation and design a series of strategies to evoke a full range of sensations: gustatory, olfactory, visual and even, of the touch and the ear. -

DESCRIPCIÓN MORFOLÓGICA Y MOLECULAR DE Vanilla Sp., (ORCHIDACEAE) DE LA REGIÓN COSTA SUR DEL ESTADO DE JALISCO

UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES TROPICALES DESCRIPCIÓN MORFOLÓGICA Y MOLECULAR DE Vanilla sp., (ORCHIDACEAE) DE LA REGIÓN COSTA SUR DEL ESTADO DE JALISCO. TESIS QUE PARA OBTENER EL GRADO DE MAESTRA EN ECOLOGÍA TROPICAL PRESENTA MARÍA IVONNE RODRÍGUEZ COVARRUBIAS Comité tutorial: Dr. José María Ramos Prado Dr. Mauricio Luna Rodríguez Dr. Braulio Edgar Herrera Cabrera Dra. Rebeca Alicia Menchaca García XALAPA, VERACRUZ JULIO DE 2012 i DECLARACIÓN ii ACTA DE APROBACIÓN DE TESIS iii DEDICATORIA Esta tesis se la dedico en especial al profesor Maestro emérito Roberto González Tamayo sus enseñanzas y su amistad. También a mis padres, hermanas y hermano; por acompañarme siempre y su apoyo incondicional. iv AGRADECIMIENTO A CONACyT por el apoyo de la beca para estudios de posgrado Número 41756. Así como al Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales por darme la oportunidad del Posgrado y al coordinador Odilón Sánchez Sánchez por su apoyo para que esto concluyera. Al laboratorio de alta tecnología de Xalapa (LATEX), Doctor Mauricio Luna Rodríguez por darme la oportunidad de trabajar en el laboratorio, asi como los reactivos. A mis compañeros que me apoyaron Marco Tulio Solórzano, Sergio Ventura Limón, Maricela Durán, Moisés Rojas Méndez y Gabriel Masegosa. A Colegio de Postgraduados (COLPOS) de Puebla por el apoyo recibido durante mis estancias y el trato humano. En especial al Braulio Edgar Herrera Cabrera, Adriana Delgado, Víctor Salazar Rojas, Maximiliano, Alberto Gil Muños, Pedro Antonio López, por compartir sus conocimientos, su amistad y el apoyo. A los investigadores de la Universidad Veracruzana Armando J. Martínez Chacón, Lourdes G. Iglesias Andreu, Pablo Octavio, Rebeca Alicia Menchaca García, Antonio Maruri García, José María Ramos Prado, Angélica María Hernández Ramírez, Santiago Mario Vázquez Torres y Luz María Villareal, por sus valiosas observaciones. -

A New Species of Vanilla (Orchidaceae) from the North West Amazon in Colombia

Phytotaxa 364 (3): 250–258 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/pt/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.364.3.4 A new species of Vanilla (Orchidaceae) from the North West Amazon in Colombia NICOLA S. FLANAGAN1*, NHORA HELENA OSPINA-CALDERÓN2, LUCY TERESITA GARCÍA AGAPITO3, MISAEL MENDOZA3 & HUGO ALONSO MATEUS4 1Departamento de Ciencias Naturales y Matemáticas, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana-Cali, Colombia; e-mail: nsflanagan@javeri- anacali.edu.co 2Doctorado en Ciencias-Biología, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia 3Resguardo Indígena Remanso-Chorrobocón, Guainía, Colombia 4North Amazon Travel & HBC, Inírida, Guainía, Colombia Abstract A distinctive species, Vanilla denshikoira, is described from the North West Amazon, in Colombia, within the Guiana Shield region. The species has morphological features similar to those of species in the Vanilla planifolia group. It is an impor- tant addition to the vanilla crop wild relatives, bringing the total number of species in the V. planifolia group to 21. Vanilla denshikoira is a narrow endemic, known from only a single locality, and highly vulnerable to anthropological disturbance. Under IUCN criteria it is categorized CR. The species has potential value as a non-timber forest product. We recommend a conservation program that includes support for circa situm actions implemented by the local communities. Introduction The natural vanilla flavour is derived from the cured seedpods of orchid species in the genus Vanilla Plumier ex Miller (1754: without page number). Vanilla is one of the most economically important crops for low-elevation humid tropical and sub-tropical regions, and global demand for this natural product is increasing. -

Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla Siamensis (Rolfe Ex Downie) in Thailand

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Chaipanich, Vinan Vince (2020) Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla siamensis (Rolfe ex Downie) in Thailand. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/85312/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Ecology and Ex Situ Conservation of Vanilla siamensis (Rolfe ex Downie) in Thailand By Vinan Vince Chaipanich November 2020 A thesis submitted to the University of Kent in the School of Anthropology and Conservation, Faculty of Social Sciences for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract A loss of habitat and climate change raises concerns about change in biodiversity, in particular the sensitive species such as narrowly endemic species. Vanilla siamensis is one such endemic species. -

Conservation & Sustainable Production of Vanilla in Costa Rica

Conservation & Sustainable Production of Vanilla in Costa Rica Charlotte Watteyn, PhD student KU Leuven Promotor: Prof. Dr. Ir. Bart Muys Copromotors: Dr. Ir. Bert Reubens Prof. Amelia Paniagua Vasquez Prof. Dr. Adam Karremans Flower Vanilla trigonocarpa The Spice “Vanilla” • Orchidaceae • Vanilloideae • Vanilla (genus) Non-aromatic species Aromatic species (Xanata) Vanilla inodora Vanilla hartii Vanilla odorata Vanilla hartii Vanilla trigonocarpa Genus Vanilla Plum. ex Mill. - +/- 120 species - Pantropic genus - BUT aromatic species (Xanata): Neotropics - 33 aromatic species known so far - Still to be discovered Vanilla species in Costa Rica Vanilla costa rica Fragrant Vanilla dressleri Fragrant Vanilla hartii Fragrant Vanilla helleri ? Vanilla inodora Non-fragrant Vanilla insignis ? Vanilla karen-christianae (2018) Fragrant Vanilla odorata Fragrant Vanilla phaeantha Fragrant Vanilla pompona Fragrant Vanilla planifolia Fragrant Vanilla sarapiquensis ? Vanilla sotoarenasi (2017) Fragrant Vanilla trigonocarpa Fragrant CURRENT SITUATION PROJECT GOAL Wild aromatic species Introduced species (V. planifolia) (CWR) Hybrid (V. tahitensis) Indirect supply chain with intermediaires Direct supply chain between farmer and consumer CURRENT SITUATION PROJECT GOAL Wild aromatic species Introduced species (V. planifolia) (CWR) Hybrid (V. tahitensis) Indirect supply chain with intermediaires Direct supply chain between farmer and consumer Study Area Southwest Costa Rica Area de Conservación Osa (ACCOSA) Unsustainable Agriculture & Illegal Logging monocultures -

Biodiversity and Evolution in the Vanilla Genus

1 Biodiversity and Evolution in the Vanilla Genus Gigant Rodolphe1,2, Bory Séverine1,2, Grisoni Michel2 and Besse Pascale1 1University of La Reunion, UMR PVBMT 2CIRAD, UMR PVBMT, France 1. Introduction Since the publication of the first vanilla book by Bouriquet (1954c) and the more recent review on vanilla biodiversity (Bory et al., 2008b), there has been a world regain of interest for this genus, as witnessed by the recently published vanilla books (Cameron, 2011a; Havkin-Frenkel & Belanger, 2011; Odoux & Grisoni, 2010). A large amount of new data regarding the genus biodiversity and its evolution has also been obtained. These will be reviewed in the present paper and new data will also be presented. 2. Biogeography, taxonomy and phylogeny 2.1 Distribution and phylogeography Vanilla Plum. ex Miller is an ancient genus in the Orchidaceae family, Vanilloideae sub- family, Vanilleae tribe and Vanillinae sub-tribe (Cameron, 2004, 2005). Vanilla species are distributed throughout the tropics between the 27th north and south parallels, but are absent in Australia. The genus is most diverse in tropical America (52 species), and can also be found in Africa (14 species) and the Indian ocean islands (10 species), South-East Asia and New Guinea (31 species) and Pacific islands (3 species) (Portères, 1954). From floral morphological observations, Portères (1954) suggested a primary diversification centre of the Vanilla genus in Indo-Malaysia, followed by dispersion on one hand from Asia to Pacific and then America, and on the other hand from Madagascar to Africa. This hypothesis was rejected following the first phylogenetic studies of the genus (Cameron, 1999, 2000) which suggested a different scenario with an American origin of the genus (160 to 120 Mya) and a transcontinental migration of the Vanilla genus before the break-up of Gondwana (Cameron, 2000, 2003, 2005; Cameron et al., 1999). -

Nutrition Facts Serving Size (140G) Servings Per Container 1

BrustersBRUSTER’S Peaches PEACHES & Cream Ice ‘N Cream, CREAM Dish ICERegular CREAM - DISH - SM Nutrition Facts Serving Size (140g) Servings Per Container 1 Amount Per Serving Calories 230 Calories from Fat 80 % Daily Value* Total Fat 8g 13% Saturated Fat 5g 24% Trans Fat 0g Cholesterol 25mg 8% Sodium 50mg 2% Total Carbohydrate 37g 12% Dietary Fiber 0g 1% Sugars 32g Protein 2g Vitamin A 8% • Vitamin C 25% Calcium 8% • Iron 4% * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. Your daily values may be higher or lower depending on your calorie needs: Calories: 2,000 2,500 Total Fat Less than 65g 80g Saturated Fat Less than 20g 25g Cholesterol Less than 300mg 300mg Sodium Less than 2,400mg 2,400mg Total Carbohydrate 300g 375g Dietary Fiber 25g 30g Ingredients: VANILLA ICE CREAM: MILK, CREAM, SUGAR, CORN SYRUP, NONFAT MILK SOLIDS, SWEET WHEY, MONO & DIGLYCERIDES, GUAR GUM, LOCUST BEAN GUM, POLYSORBATE 80, CARRAGEENAN, VANILLA, VANILLIN, NATURAL FLAVOR, CARAMEL COLOR. PEACH SORBET: WATER, SUGAR, PEACHES, CORN SYRUP, CITRIC ACID, GUAR GUM, XANTHAN GUM, SODIUM BENZOATE (A PRESERVATIVE), NATURAL FLAVOR, AND YELLOW 6. Vertical, Full Thursday, May 26, 2011 BRUSTER’SBrusters Peaches PEACHES & Cream Ice ‘N Cream, CREAM Dish ICERegular CREAM +1 - DISH - REG Nutrition Facts Serving Size (210g) Servings Per Container 1 Amount Per Serving Calories 350 Calories from Fat 110 % Daily Value* Total Fat 13g 19% Saturated Fat 7g 37% Trans Fat 0g Cholesterol 35mg 12% Sodium 70mg 3% Total Carbohydrate 55g 18% Dietary Fiber 0g 1% Sugars 48g Protein 3g Vitamin A 10% • Vitamin C 35% Calcium 10% • Iron 6% * Percent Daily Values are based on a 2,000 calorie diet. -

PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE INTRODUCTION to the FABACEAE

1 PHASEOLUS LESSON ONE PHASEOLUS and the FABACEAE In this lesson we will begin our study of the GENUS Phaseolus, a member of the Fabaceae family. The Fabaceae are also known as the Legume Family. We will learn about this family, the Fabaceae and some of the other LEGUMES. When we study about the GENUS and family a plant belongs to, we are studying its TAXONOMY. For this lesson to be complete you must: ___________ do everything in bold print; ___________ answer the questions at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the world map at the end of the lesson; ___________ complete the table at the end of the lesson; ___________ learn to identify the different members of the Fabaceae (use the study materials at www.geauga4h.org); and ___________ complete one of the projects at the end of the lesson. Parts of the lesson are in underlined and/or in a different print. Younger members can ignore these parts. WORDS PRINTED IN ALL CAPITAL LETTERS may be new vocabulary words. For help, see the glossary at the end of the lesson. INTRODUCTION TO THE FABACEAE The genus Phaseolus is part of the Fabaceae, or the Pea or Legume Family. This family is also known as the Leguminosae. TAXONOMISTS have different opinions on naming the family and how to treat the family. Members of the Fabaceae are HERBS, SHRUBS and TREES. Most of the members have alternate compound leaves. The FRUIT is usually a LEGUME, also called a pod. Members of the Fabaceae are often called LEGUMES. Legume crops like chickpeas, dry beans, dry peas, faba beans, lentils and lupine commonly have root nodules inhabited by beneficial bacteria called rhizobia. -

The Lipstick Tree

The lipstick tree MARY CAREY-SCHNEIDER grows Bixa orellana as an ornamental on her estate in Argentina but elsewhere it is grown commercially for the colouring agent obtained from the ripe fruit and seeds. Locally called annatto or achiote, the fruits of Bixa orellana have satisfied two important areas of man’s needs for many centuries, fulfilling both basic dietary demands as a spice or colorant in a myriad of recipes across the Central and Latin American continent, and his spiritual aspirations and vanity as a face and body photograph © Mary Carey-Schneider 40 Bixa orellana, the lipstick tree, growing as an ornamental in Argentina. It is from the dark red seed and pods that dye is extracted. For illustration of the seed, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Bixa_orellana_seeds.jpg paint. From the Caribbean to the Incas and the Amazon indigenous peoples, the orange-red pigment from this small tree has been used in everyday life as well as on feast-days and high days, forming part of their way of living. The so-called lipstick tree is an easily grown shrub that bears fruit prolifically; one of four genera in the family Bixaceae, it is found from the southern Caribbean to the South American tropics. Its common name in English is derived from the pigment made from the abundant seeds that are made into face and body paints. Although it is also used as a food and fabric pigment the crushed seeds also have some medicinal use, as it is said to be hallucinogenic and a mild diuretic.