Protecting Our Green Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protected Landmark Designation Report

CITY OF HOUSTON Archaeological & Historical Commission Planning and Development Department PROTECTED LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT LANDMARK NAME: Sam Houston Park (originally known as City Park) AGENDA ITEM: III.a OWNER: City of Houston HPO FILE NO.: 06PL33 APPLICANT: City of Houston Parks and Recreation Department and DATE ACCEPTED: Oct-20-06 The Heritage Society LOCATION: 1100 Bagby Street HAHC HEARING DATE: Dec-21-06 30-DAY HEARING NOTICE: N/A PC HEARING DATE: Jan-04-07 SITE INFORMATION: Land leased from the City of Houston, Harris County, Texas to The Heritage Society authorized by Ordinance 84-968, dated June 20, 1984 as follows: Tract 1: 42, 393 square feet out of Block 265; Tract 2: 78,074 square feet out of Block 262, being part of and out of Sam Houston Park, in the John Austin Survey, Abstract No. 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein; and Tract 3: 11,971 square feet out of Block 264, S. S. B. B., and part of Block 54, Houston City Street Railway No. 3, John Austin Survey, Abstract 1, more fully described by metes and bounds therein, Houston, Harris County, Texas. TYPE OF APPROVAL REQUESTED: Landmark and Protected Landmark Designation for Sam Houston Park. The Kellum-Noble House located within the park is already designated as a City of Houston Landmark and Protected Landmark. HISTORY AND SIGNIFICANCE SUMMARY: Sam Houston Park is the first and oldest municipal park in the city and currently comprises nineteen acres on the edge of the downtown business district, adjacent to the Buffalo Bayou parkway and Bagby Street. -

30Th Anniversary of the Center for Public History

VOLUME 12 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2015 HISTORY MATTERS 30th Anniversary of the Center for Public History Teaching and Collection Training and Research Preservation and Study Dissemination and Promotion CPH Collaboration and Partnerships Innovation Outreach Published by Welcome Wilson Houston History Collaborative LETTER FROM THE EDITOR 28½ Years Marty Melosi was the Lone for excellence in the fields of African American history and Ranger of public history in our energy/environmental history—and to have generated new region. Thirty years ago he came knowledge about these issues as they affected the Houston to the University of Houston to region, broadly defined. establish and build the Center Around the turn of the century, the Houston Public for Public History (CPH). I have Library announced that it would stop publishing the been his Tonto for 28 ½ of those Houston Review of History and Culture after twenty years. years. Together with many others, CPH decided to take on this journal rather than see it die. we have built a sturdy outpost of We created the Houston History Project (HHP) to house history in a region long neglectful the magazine (now Houston History), the UH-Oral History of its past. of Houston, and the Houston History Archives. The HHP “Public history” includes his- became the dam used to manage the torrent of regional his- Joseph A. Pratt torical research and training for tory pouring out of CPH. careers outside of writing and teaching academic history. Establishing the HHP has been challenging work. We In practice, I have defined it as historical projects that look changed the format, focus, and tone of the magazine to interesting and fun. -

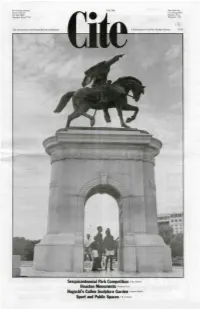

Sesquicentennial Park Competition **« N*»« Houston

Rice Design Alliance Fall 1986 Non-Pmfil Org. Rice University U.S. Postage Paid P.O. Box 1892 Houston. Texas Houslon, Texas 77251 Permit No. 754" The Architecture and Design Review of Houston \ Publication oflhe Rice Design Alliance $3.00 Sesquicentennial Park Competition **« n*»« Houston Monuments Stephen FOX Noguchi's Cullen Sculpture Garden ^-» »••«'- Sport and Public SpacesJ B •'«•«» Cite Flit 1986 InCite 4 Citelines 8 ForeCite L\ 8 The Sesquicentennial Park Design Competition Cite 12 Remember Houston 14 Romancing the Stone: The Cullen Sculpture Garden PlANTS 16 Fields of Play: Sport and Public Spaces Cover: Sam Houston Monument. Hermann 17 Citesurvey: Rubenstein Park. 1925, Enrico F. Cerracchio. sculptor. Group Building J. W. Northrop. Jr., architect (Photo by 18 Citeations ARETHE Paul Hester) 23 Hind Cite NATURE Editorial Committee Thomas Colbert Neil Printz John Gilderbloom Malcolm Quantril! Bruce C. Webb Elizabeth S. Glassman Eduardo Robles Chairman David Kaplan William F. Stern Phillip Lopate Drexel Turner OF OUR Jeffrey Karl Ochsner Peter D. Waldman BUSINESS Guest Editor: Drexel Turner The opinions expressed in Cite do not Managing Editor: Linda Leigh Sylvan necessarily represent the views of the Editorial Assistant: Nancy P, Henry Board of Directors of the Rice Design Graphic Designer: Alisa Bales Alliance. Typesetting and Production: Baxt & Associates Cite welcomes unsolicited manuscripts. Director of Advertising: Authors take full responsibility for Kathryn Easterly securing required consents and releases Publisher: Lynette M. Gannon and for the authenticity of their articles. All manuscripts will be considered by the During our thirty years in business The Spencer Company's client list Publication of this issue of Cite is Editorial Board. -

FARRAR-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (13.02Mb)

THE MILAM STREET BRIDGE ARTIFACT ASSEMBLAGE: HOUSTONIANS JOINED BY THE COMMON THREAD OF ARTIFACTS – A STORY SPANNING FROM THE CIVIL WAR TO MODERN DAY A Dissertation by JOSHUA ROBERT FARRAR Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Luis F. M. Vieira De Castro Committee Members, Donny L. Hamilton Christopher M. Dostal Joseph G. Dawson III Anthony M. Filippi Head of Department, Darryl J. De Ruiter May 2020 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2020 Joshua R. Farrar ABSTRACT Buffalo Bayou has connected Houston, Texas to Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico since Houston’s founding in 1837. During the American Civil War of 1861-65, Houston served as a storehouse for weapons, ammunition, food, clothing, and other supplies destined for the war effort in Galveston and the rest of the Confederacy. Near the end or soon after the Civil War ended, Confederate material supplies were lost or abandoned in Buffalo Bayou under the Milam Street Bridge in Houston. In 1968, the Southwestern Historical Exploration Society (SHES) recovered around 1000 artifacts with an 80-ton dragline crane operated off the Milam Street Bridge. About 650 artifacts from this collection were rediscovered by the Houston Archeological Society in 2015, stored in filing boxes at the Heritage Society at Sam Houston Park. This dissertation serves as an artifact and document-based study using newspaper accounts, sworn statements, and archaeological reports to assemble and detail the history of the Milam Street Artifact Assemblage – from abandonment in the bayou to rediscovery at the Heritage Society. -

Houston-Galveston, Texas Managing Coastal Subsidence

HOUSTON-GALVESTON, TEXAS Managing coastal subsidence TEXAS he greater Houston area, possibly more than any other Lake Livingston A N D S metropolitan area in the United States, has been adversely U P L L affected by land subsidence. Extensive subsidence, caused T A S T A mainly by ground-water pumping but also by oil and gas extraction, O C T r has increased the frequency of flooding, caused extensive damage to Subsidence study area i n i t y industrial and transportation infrastructure, motivated major in- R i v vestments in levees, reservoirs, and surface-water distribution facili- e S r D N ties, and caused substantial loss of wetland habitat. Lake Houston A L W O Although regional land subsidence is often subtle and difficult to L detect, there are localities in and near Houston where the effects are Houston quite evident. In this low-lying coastal environment, as much as 10 L Galveston feet of subsidence has shifted the position of the coastline and A Bay T changed the distribution of wetlands and aquatic vegetation. In fact, S A Texas City the San Jacinto Battleground State Historical Park, site of the battle O Galveston that won Texas independence, is now partly submerged. This park, C Gulf of Mexico about 20 miles east of downtown Houston on the shores of Galveston Bay, commemorates the April 21, 1836, victory of Texans 0 20 Miles led by Sam Houston over Mexican forces led by Santa Ana. About 0 20 Kilometers 100 acres of the park are now under water due to subsidence, and A road (below right) that provided access to the San Jacinto Monument was closed due to flood- ing caused by subsidence. -

Printable Schedule

CALENDAR OF EVENTS AUGUST – NOVEMBER 2021 281-FREE FUN (281-373-3386) | milleroutdoortheatre.com Photo by Nash Baker INFORMATION Glass containers are prohibited in all City of Houston parks. If you are seated Location in the covered seating area, please ensure that your cooler is small enough to fit under your seat in case an emergency exit is required. 6000 Hermann Park Drive, Houston, TX 77030 Smoking Something for Everyone Smoking is prohibited in Hermann Park and at Miller Outdoor Theatre, including Miller offers the most diverse season of professional entertainment of any Houston the hill. performance venue — musical theater, traditional and contemporary dance, opera, classical and popular music, multicultural performances, daytime shows for young Recording, Photography, & Remote Controlled Vehicles audiences, and more! Oh, and it’s always FREE! Audio/visual recording and/or photography of any portion of Miller Outdoor Theatre Seating presentations require the express written consent of the City of Houston. Launching, landing, or operating unmanned or remote controlled vehicles (such as drones, Tickets for evening performances are available online at milleroutdoortheatre.com quadcopters, etc.) within Miller Outdoor Theatre grounds— including the hill and beginning at 9 a.m. two days prior to the performance until noon on the day of plaza—is prohibited by park rules. performance. A limited number of tickets will be available at the Box Office 90 minutes before the performance. Accessibility Face coverings/masks are strongly encouraged for all attendees in the Look for and symbols indicating performances that are captioned for the covered seats and on the hill, unless eating or drinking, especially those hearing-impaired or audio described for the blind. -

07-77817-02 Final Report Dickinson Bayou

Dickinson Bayou Watershed Protection Plan February 2009 Dickinson Bayou Watershed Partnership 1 PREPARED IN COOPERATION WITH TEXAS COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY AND U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY The preparation of this report was financed though grants from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency through the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 7 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................................................. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................. 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 10 SUMMARY OF MILESTONES ........................................................................................................................ 13 FORWARD ................................................................................................................................................... 17 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................... 18 The Dickinson Bayou Watershed .................................................................................................................. -

Houston Astrodome Harris County, Texas

A ULI Advisory ServicesReport Panel A ULI Houston Astrodome Harris County, Texas December 15–19, 2014 Advisory ServicesReport Panel A ULI Astrodome2015_cover.indd 2 3/16/15 12:56 PM The Astrodome Harris County, Texas A Vision for a Repurposed Icon December 15–19, 2014 Advisory Services Panel Report A ULI A ULI About the Urban Land Institute THE MISSION OF THE URBAN LAND INSTITUTE is ■■ Sustaining a diverse global network of local practice to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in and advisory efforts that address current and future creating and sustaining thriving communities worldwide. challenges. ULI is committed to Established in 1936, the Institute today has more than ■■ Bringing together leaders from across the fields of real 34,000 members worldwide, representing the entire estate and land use policy to exchange best practices spectrum of the land use and development disciplines. and serve community needs; ULI relies heavily on the experience of its members. It is through member involvement and information resources ■■ Fostering collaboration within and beyond ULI’s that ULI has been able to set standards of excellence in membership through mentoring, dialogue, and problem development practice. The Institute has long been rec- solving; ognized as one of the world’s most respected and widely ■■ Exploring issues of urbanization, conservation, regen- quoted sources of objective information on urban planning, eration, land use, capital formation, and sustainable growth, and development. development; ■■ Advancing land use policies and design practices that respect the uniqueness of both the built and natural environments; ■■ Sharing knowledge through education, applied research, publishing, and electronic media; and Cover: Urban Land Institute © 2015 by the Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW Suite 500 West Washington, DC 20007-5201 All rights reserved. -

The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: a Chronicle of Colonel J.G

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 33 Issue 2 Article 7 10-1995 The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: A Chronicle of Colonel J.G. Kellersberger, the Confederate Chief Engineer of East Texas W. T. Block Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Block, W. T. (1995) "The Ghostly-Silent Guns of Galveston: A Chronicle of Colonel J.G. Kellersberger, the Confederate Chief Engineer of East Texas," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol33/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORlCAL ASSOCIATION THE GHOSTLY·SILENT GUNS OF GALVESTON: A CHRONICLE OF COLONEL J.G. KELLERSBERGER, THE CONFEDERATE CHIEF ENGINEER OF EAST TEXAS by WT. Block Tn 1896, as wintry blasts swept down the valley of the River Aare in northern Switzerland, an old man consumed endless hours in his ancestral home, laboring to complete a manuscript. With his hair and beard as snow capped as the neighboring Alpine peaks, Julius Getulius Kellersberger, who felt that life was fast ebbing from his aging frame, wrote and rewrote each page with an engineer~s masterful precision, before shipping the finished version of his narrative to Juchli and Beck, book publishers of Zurich.] After forty-nine years in America, Kellersberger, civil engineer, former Forty-oiner, San Francisco Vigilante, surveyor~ town, bridge, and railroad builder; and Confederate chief engineer for East Texas, bade farewell to a son and four daughters, his grandchildren~ and the grave of his wife, all located at Cypress Mill, Blanco County, Texas. -

Rider Guide / Guía De Pasajeros

Updated 02/10/2019 Rider Guide / Guía de Pasajeros Stations / Estaciones Stations / Estaciones Northline Transit Center/HCC Theater District Melbourne/North Lindale Central Station Capitol Lindale Park Central Station Rusk Cavalcade Convention District Moody Park EaDo/Stadium Fulton/North Central Coffee Plant/Second Ward Quitman/Near Northside Lockwood/Eastwood Burnett Transit Center/Casa De Amigos Altic/Howard Hughes UH Downtown Cesar Chavez/67th St Preston Magnolia Park Transit Center Central Station Main l Transfer to Green or Purple Rail Lines (see map) Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Westbound – Central Station Capitol Eastbound – Central Station Rusk Eastbound Theater District to Magnolia Park Hacia el este Magnolia Park Main Street Square Bell Westbound Magnolia Park to Theater District Downtown Transit Center Hacia el oeste Theater District McGowen Ensemble/HCC Wheeler Transit Center Museum District Hermann Park/Rice U Stations / Estaciones Memorial Hermann Hospital/Houston Zoo Theater District Dryden/TMC Central Station Capitol TMC Transit Center Central Station Rusk Smith Lands Convention District Stadium Park/Astrodome EaDo/Stadium Fannin South Leeland/Third Ward Elgin/Third Ward Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales TSU/UH Athletics District Northbound Fannin South to Northline/HCC UH South/University Oaks Hacia el norte Northline/HCC MacGregor Park/Martin Luther King, Jr. Southbound Northline/HCC to Fannin South Palm Center Transit Center Hacia el sur Fannin South Destination Signs / Letreros Direccionales Eastbound Theater District to Palm Center TC Hacia el este Palm Center Transit Center Westbound Palm Center TC to Theater District Hacia el oeste Theater District The Fare/Pasaje / Local Make Your Ride on METRORail Viaje en METRORail Rápido y Fare Type Full Fare* Discounted** Transfer*** Fast and Easy Fácil Tipo de Pasaje Pasaje Completo* Descontado** Transbordo*** 1. -

SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History Through the Ages by Wallace W

PRESERVATION The 1847 Kellum-Noble House served as Houston Parks Department headquarters for many years. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS, Reproduction number HABS TEX, 101-HOUT, 4-1. SAM HOUSTON PARK: Houston History through the Ages By Wallace W. Saage he history of Texas and the history of the city grant from Austin’s widow, Mrs. J. F. L. Parrot, and laid Tof Houston are inextricably linked to one factor out a new city.1 They named it Houston. – land. Both Texas and Houston used the legacy of The growth of Sam Houston Park, originally called the land to encourage settlement, bringing in a great City Park, has always been closely related to the transfer multicultural mélange of settlers that left a lasting im- of land, particularly the physical and cultural evolution pression on the state. An early Mexican land grant to of Houston’s downtown region that the park borders. John Austin in 1824 led to a far-reaching development Contained within the present park boundaries are sites ac- plan and the founding of a new city on the banks of quired by the city from separate entities, which had erected Buffalo Bayou. In 1836, after the Republic of Texas private homes, businesses, and two cemeteries there. won its independence, brothers John Kirby Allen and Over the years, the city has refurbished the park, made Augustus C. Allen purchased several acres of this changes in the physical plant, and accommodated the increased use of automobiles to access a growing downtown. The greatest transformation of the park, however, grew out of the proposed demoli- tion of the original Kellum House built on the site in 1847. -

The Jewish Mardi Gras? Celebrate Purim with Emanu

March 3, 2020 I 7 Adar 5780 Bulletin VOLUME 74 NUMBER 6 FROM RABBI HAYON Sisterhood to Host Barbara Pierce Bush as 2020 The Jewish Mardi Gras? Fundraiser Speaker Now that March is here, we have arrived at Thursday, March 26, 11:30 a.m. what is said to be the most joyous time of Congregation the Jewish year. We are now in the Hebrew Emanu El month of Adar, and our tradition teaches: Sisterhood, in “When Adar begins, rejoicing multiplies.” partnership with the Barbara Jewish happiness reaches its apex during Adar because Bush Literacy it is the time of Purim, when convention and inhibition Foundation and Purim’s purpose is dissipate. During Purim we allow ourselves to indulge in Harris County to help us realize all sorts of fun as a way of commemorating our people’s Public Library, the potential of miraculous escape from Haman’s wicked plot in the an- will hold its transformative cient kingdom of Persia. annual fundraising event, Words joy, but it insists Change the World this month. This that enduring But we are not alone in our religious celebrations at this time of year. We’re all familiar with the raucous traditions year’s guest speaker will be Barbara happiness emerges Pierce Bush, humanitarian and co- less from satisfying associated with Mardi Gras, but we don’t often pause to recall that those celebrations are also rooted in religious founder and Board Chair of Global our own appetites Health Corps. than from working traditions of their own: the reason for the Christian tra- dition of indulging on Fat Tuesday is that it occurs imme- for the preserva- A Yale University graduate with a tion of others.