CDOT Geotechnical Design Manual 5 AASHTO LRFD Bridge Design Specifications (Customary U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloping and Benching Systems

Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING AND BENCHING SYSTEMS OBJECTIVES Upon the completion of this section, the participant should be able to: 1. Describe the difference between maximum allowable slope and actual slope. 2. Observe how the angle of various sloped systems varies with soil type. 3. Evaluate layered systems to determine the proper trench slope. 4. Illustrate how shield systems and sloping systems interface in combination systems. ©HMTRI 2000 Page 42 Trenching REV1 Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING SYSTEMS If enough surface room is available, sloping or benching the trench walls will offer excellent protection without any additional equipment. Cutting the slope of the excavation back to its prescribed angle will allow the forces of cohesion (if present) and internal friction to hold the soil together and keep it from flowing downs the face of the trench. The soil type primarily determines the excavation angle. Sloping a method of protecting employees from caveins by excavating to form sides of an excavation that are inclined away from the excavations so as to prevent caveins. In practice, it may be difficult to accurately determine these sloping angles. Most of the time, the depth of the trench is known or can easily be determined. Based on the vertical depth, the amount of cutback on each side of the trench can be calculated. A formula to calculate these cutback distances will be included with each slope diagram. NOTE: Remember, the beginning of the cutback distance begins at the toe of the slope, not the center of the trench. Accordingly, the cutback distance will be the same regardless of how wide the trench is at the bottom. -

Engineering Bulletin 07-009

To: New York State Department of EB Transportation ENGINEERING 07-009 BULLETIN Expires one year after issue unless replaced sooner Title: HIGHWAY DESIGN MANUAL (HDM) REVISION NO. 52 CHAPTER 9 - SOILS, WALLS, AND FOUNDATIONS CHAPTER 20.00 –CANTILEVER AND GRAVITY WALLS Distribution: Approved: Manufacturers (18) Surveyors (33) Local Govt. (31) Consultants (34) Agencies (32) Contractors (39) /s/Daniel D’Angelo________________ 3/2/07____ ____________( ) Daniel D’Angelo, P.E. Date Deputy Chief Engineer, Design ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION: Effective Date: This Engineering Bulletin (EB) is effective upon signature. Superseded Issuance(s): No Engineering Instructions or EBs are superseded by this EB. PURPOSE: To announce the availability of Revision No. 52 to the HDM and to rescind HDM Chapter 20.00 –Cantilever and Gravity Walls. TECHNICAL INFORMATION: Chapter 9. HDM users should replace their entire existing Chapter 9 dated June 7, 1995, and revised July 9, 2004, with the updated version dated March 2, 2007. Chapter 9 has been revised to clarify, update, and add material. Although the entire chapter is being issued, not all material has been revised. Noteworthy changes are as follows: . Section 9.3 “Soil and Foundation Considerations” was expanded to include the following: “Embankment Foundation.” This subsection combines previous subsections including “Unsuitable Material” and “Unstable Material.” “Water Quality.” This subsection replaces the previous “Erosion and Sedimentation” subsection. “Excavation Protection and Support.” This subsection replaces the previous “Trench, Culvert, and Structure Excavation” subsection. “Controlled Low-Strength Material (CLSM).” This is a new subsection. “Contract Information” was moved from Section 9.4 to Section 9.7 and Section 9.4 is retitled “Retaining Walls and Reinforced Soil Slopes and Walls.” This section incorporates the former HDM Chapter 20.00 “Cantilever and Gravity Walls.” . -

Assessment of Pavement Foundation Stiffness Using Cyclic Plate Load Test

Assessment of Pavement Foundation Stiffness using Cyclic Plate Load Test Mark H. Wayne & Jayhyun Kwon Tensar International Corporation, Alpharetta, U.S.A. David J. White R.L. Handy Associate Professor of Civil Engineering, Department of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa ABSTRACT: The quality of the pavement foundation layer is critical in performance and sustainability of the pavement. Over the years, various soil modification or stabilization methods were developed to achieve sufficient bearing performance of soft subgrade. Geogrid, through its openings, confine aggre- gates and forms a stabilized composite layer of aggregate fill and geogrid. This mechanically stabilized layer is used to provide a stable foundation layer for roadways. Traditional density-based QC plans and associated QA test methods such as nuclear density gauge are limited in their ability to assess stiffness of stabilized composite layers. In North America, non-destructive testing methods, such as falling weight de- flectometer (FWD) and light weight deflectometer (LWD) are used as stiffness- or strength-based QA test methods. In Germany and some other European countries, a static strain modulus (Ev2) is more commonly used to verify bearing performance of paving layers. Ev2 is a modulus measured on second load stage of the static plate load test. In general, modulus determined from first load cycle is not reliable because there is too much re-arrangement of the gravel particles. However, a small number of load cycles may not be sufficiently dependable or reliable to be used as a design parameter. Experiments were conducted to study the influence of load cycles in bearing performance. -

Earthwork Design and Construction

Technical Fundamentals for Design and Construction April 6, 2020 Earthwork Design and Construction Key Points • The primary objectives of earthwork operations are: (1) to increase soil bearing capacity; (2) control shrinkage and swelling; and (3) reduce permeability. • Particle shape is a critical physical soil property influencing engineering modification of a soil. • Proper water content is essential to economically achieve specified soil density. Purpose and Scope of Earthwork The purpose and scope of earth construction differ for various types of constructed facilities. The major types of earthwork projects include: • Transportation projects, which require embankments, roadways, and bridge approaches. • Water control, which usually involves dams, levies, and canals. • Landfill closures, which need impervious caps. • Building foundations, which must support loads and limit soil movement by shrinkage and swelling. Properly modified soils are the most economical solution for many constructed facilities. To meet structural support requirements, soils at some project sites may require treatment such as the addition of water, lime, or cement. 1 Technical Fundamentals for Earthwork Design, Materials, and Resources The physical chemical properties of project site soils have a major influence on the design of earthen structures and on the resources and operations needed to properly modify a soil. The fundamental properties of a soil include: granularity, course to fine; water content; specific gravity; and particle size distribution. Other properties include permeability, shear strength, and bearing capacity. The engineering design of a soil seeks to provide sufficient bearing capacity, settlement control, and either limit, in the case of dams and landfill caps, the movement of water or facilitate the movement of water in the case of drains, such as behind retaining walls. -

Failure of Slopes and Embankments Under Static and Seismic Loading

American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS) ISSN (Print) 2313-4410, ISSN (Online) 2313-4402 © Global Society of Scientific Research and Researchers http://asrjetsjournal.org/ Failure of Slopes and Embankments Under Static and Seismic Loading Nicolaos Alamanis* Lecturer, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Technological Educational Institute of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece, Civil engineer (National Technical University of Athens, D.E.A Ecole Centrale Paris) Email: [email protected] Summary The stability of slopes and embankments under the influence of static and seismic loads has been the subject of study for many researchers. This paper presents the mechanisms and causes of landslides as well as the forms of failure of slopes and embankments under static and seismic loading, with examples of failures from both Greek and international space. There is also mention to measures to protect and stabilize landslides, categories of slope stability analysis, and methods of seismic impact analysis. What follows is the determination of tolerable movements based on the caused damage on natural slopes, dams and embankments and an attempt is made to connect them with the vulnerability curves that are one of the key elements of stochastic seismic hazard. Particular importance is given to the statistical parameters of the mechanical characteristics of the sloping soil mass and to the simulation of random fields necessary for solving complex geotechnical works. Finally, we compare the simulation and description of random fields and the L.A.S. method is observed to be the most accurate of all simulation methods. The L.A.S. algorithm in conjunction with finite difference models can demonstrate the large fluctuations in the factor of safety values and the permanent seismic displacements of the slopes under the effect of seismic charges whose time histories are known. -

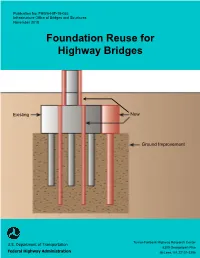

Foundation Reuse for Highway Bridges

Publication No. FHWA-HIF-18-055 Infrastructure Office of Bridges and Structures November 2018 Foundation Reuse for Highway Bridges Existing New Ground Improvement Turner-Fairbank Highway Research Center U.S. Department of Transportation 6300 Georgetown Pike Federal Highway Administration McLean, VA 22101-2296 FOREWORD Given the high percentage of deteriorated or obsolete bridges in the national bridge inventory, the reuse of bridge foundations may be a viable option that can present a significant cost savings in bridge replacement and rehabilitation efforts. The potential time savings associated with foundation reuse can, in turn, reduce mobility impacts and increase the economic viability and sustainability of a project. However, existing foundations may have uncertain material properties, geometry, or details that impact the risks associated with reuse. Unlike a new foundation, an existing foundation may have been damaged, may not have sufficient capacity, and may have limited remaining service life due to deterioration. Assessment of these issues as well as foundation strengthening and repair measures and innovative approaches to optimize loading are discussed in this report. To better demonstrate the engineering assessment of key integrity, durability and load carrying capacity issues, the report contains fifteen (15) case examples where foundation was reused by the owner agencies. On new construction, the report looks ahead and includes discussions on foundation design with consideration for reuse. Cheryl Allen Richter, P.E., Ph.D. Director, Office of Infrastructure Research and Development Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the use of the information contained in this document. -

Engineering Geological Characterisation and Slope Stability

Engineering Geological Characterisation and Slope Stability Assessment of Whitehall Quarry, Waikato. A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science in Engineering Geology at the University of Canterbury by Daniel Rodney Strang UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY 2010 I Frontispiece Whitehall Quarry “Over 4,000 tonnes of aggregate goes into every 1 km of a two lane road” II Abstract Whitehall Quarry is located 4 km east of Karapiro, near Cambridge within the Waikato District. Current quarrying operations produce between 150,000 and 300,000 tonnes of aggregate for use in the surrounding region. This study is an investigation into the engineering geological model for the quarry and pit slope stability assessment. Pit slope stability is an integral aspect of quarrying and open-pit mining since slopes should be as steep as possible to minimise waste material which needs to be removed, yet shallow enough to minimise potential hazards to personnel and equipment below pit slopes. This study also assesses the stability of complex wedge located within the north western corner of the quarry. Initial estimates approximate a wedge mass volume of 500,000 m3; failure was triggered during the late 80‟s due a stripping programme at the head of the mass. Field and laboratory investigations were carried out to identify and quantify engineering geological parameters. Photogrammetric and conventional scanline analytical techniques identified two domains within the quarry divided by the Main Quarry Shear Zone (MQSZ). Discontinuity orientations are the key differences between the two domains. Bedding planes appear to have slightly different orientations and each domain has very different joint sets identified. -

Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation

Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management G.P.O. BOX 4719, Babar Mahal, Kathmandu, Nepal Kathmandu, June 2016 T: 977-1-4220828/4220857 | F: 977-1-4221067 E: [email protected]/[email protected] (Asar 2073) W: www.dscwm.gov.np Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management Kathmandu, June 2016 (Asar 2073) Publisher Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation, Babar Mahal, Kathmandu, Nepal Cover photo credit Landslide in Rasuwa©Mr. Jagannath Joshi Credits © Department of soil Conservation and Watershed Management (DSCWM) Kathmandu, Nepal Landslide Treatment and Mitigation Sub-Group Coordinator: Mr. KesharMan Sthapit (FAO Nepal Office) Members: Mr. GehendraKeshariUpadhyaya (DSCWM) Dr. Jagannath Joshi (DSCWM) Mr. Deepak Bhardwaj (DSCWM) Mr. Shanmukhesh Chandra Amatya (Department of Water Induced Disaster Management) Ms. Laxmi Thagunna (Department of Environment) Ms. Racchya Shah (IUCN Nepal) Mr. Bhawani Shankar Dongol (WWF Nepal) Mr. Sanjay Devkota (Forum for Energy and Environment Development) Mr. Deo Raj Gurung (ICIMOD) Advisor: Mr. Purna Chandra Lal Rajbhandari (UNEP) Citation DSCWM (2016), Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation.Department of soil Conservation and Watershed Management, Kathmandu, Nepal. We are very thankful to USAID funded Hariyo Ban Program, WWF Nepal for providing support to edit, format and print this guideline. ii | Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation | iii iv | Guideline on Landslide Treatment and Mitigation Preface The working group on “Landslide Treatment and Mitigation” was established following the recommendations of the consultative workshop on “Landslide Inventory, Risk Assessment, and Mitigation” organized by the Department of Soil Conservation and Watershed Management (DSCWM) from 28-29 September 2015 at Kathmandu. -

Evaluating the Capacity of Helical Piles in Clay Tills Using Pile Load Tests

Evaluating the Capacity of Helical Piles in Clay Tills Using Pile Load Tests Ivanna Montani Stantec Consulting Ltd, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada ABSTRACT This thesis analyzes seven static load tests conducted on helical piles installed in clay till at a site in Northern Manitoba, Canada. Four methods, the Davisson Offset Limit, the Hansen Ultimate Load, the Chin-Kondner Extrapolation, and the Decourt Extrapolation are used to determine the ultimate capacity using the pile load test results. The ultimate capacities obtained were then used to determine the empirical parameter Kt for helical piles in clay tills, this parameter relates the pile capacity of helical piles to the installation torque of the pile. The Davisson Offset Limit and the Hansen Ultimate Load provided consistent and conservative ultimate capacities based on the pile load test results and showed lesser variability in results compared with the Chin-Kondner Extrapolation and Decourt Extrapolation methods. The ultimate loads based from the Hansen and Davisson methods were used to calculate a Kt value. It was determined that a Kt value ranging from 9 m-1 to 11 m-1 is appropriate for evaluating the capacity of a helical pile in clay tills using the installation torque of the pile. RÉSUMÉ Cette thèse fait l’analyse de sept essais de mise en charge statique effectués sur des pieux vissés installés dans une formation de moraine (till) argileuse dans le nord du Manitoba, au Canada. Quatre méthodes ont été utilisées pour la détermination de la capacité ultime utilisant les résultats des essais de mise en charge : la méthode de la charge limite décalée (Davisson), la méthode de la charge ultime (Hansen), ainsi que les méthodes d’extrapolation de Chin-Kondner et de Decourt. -

Accelerated Load Testing of Pavements HVS-Nordic Tests at VTI Sweden 2003–2004

VTI rapport 544A www.vti.se/publications Published 2006 Accelerated load testing of pavements HVS-Nordic tests at VTI Sweden 2003–2004 Leif G Wiman Publisher: Publication: VTI rapport 544A Published: Project code: 2006 60813 SE-581 95 Linköping Sweden Project: Accelerated load testing of pavement using Heavy Vehicle Simulator (HVS) Author: Sponsor: Leif G Wiman Swedish Road Administration Title: Accelerated load testing of pavements – HVS-Nordic tests at VTI Sweden 2003–2004 Abstract (background, aim, method, result) max 200 words: During 2003 and 2004 two accelerated load tests were performed at the VTI test facility in Sweden (SE05 and SE06). The objective of SE05 was to investigate the deformation behaviour of two different unbound base materials. Half of the test area was constructed with a base layer of natural granular material and the other half with a base layer of crushed rock aggregate. This means that the two structures were tested simultaneously. The objective of SE06 was to be the third test in a series of structural design tests with stepwise higher bearing capacity. The previous two tests in this series are SE01 and SE02. In the unbound base material test, SE05, the surface rut depth propagation during the accelerated load testing was greater on the crushed rock aggregate structure especially in wet condition. This was not expected and more than half of the difference in surface rut depth was found in the difference in the base layer deformations. One main reason for this unexpected behaviour is believed to be unsatisfactory compaction of the crushed rock aggregate. The performance of the pavement structures SE01, SE02 and SE06 during the accelerated load testing will be analysed in more detail in the future. -

Downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE)

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR SOIL MECHANICS AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING This paper was downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). The library is available here: https://www.issmge.org/publications/online-library This is an open-access database that archives thousands of papers published under the Auspices of the ISSMGE and maintained by the Innovation and Development Committee of ISSMGE. Reliability of statnamic load testing of rock socketed end bearing bored piles Fiabilité d’un essai de charge Statnamic sur un pieu résistant à la pointe foré dans de la roche H. S. Thilakasiri Department of Civil Engineering, University of Moratuwa, Sri Lanka. ABSTRACT The pile load testing methods could be broadly classified into three categories: static, rapid and dynamic depending on the rate of loading. In this paper, the rapid load testing method referred to as the Statnamic test is discussed. The commonly used analysis method of the statnamic testing referred to as the Unloading Point (UP) method is used successfully for the floating piles but validity of some of the assumptions of the unloading point method to end bearing bored piles is questionable. Due to this problem, other analytical methods such as: Modified Unloading Point (MUP) method, Segmental Unloading Point (SUP) method and other signal matching techniques are introduced by some researches. Therefore, the validity of the unloading point method to rock socketed end bearing bored piles in Sri Lanka is investigated in this paper. This investigation is carried out using the commonly used wave number. Furthermore, the wave equation method, commonly used numerical procedure to model dynamic behavior of piles, is used by the author to investigate the validity of the assumptions associated with the unloading point method to rock socketed end bearing bored piles. -

Control and Inspection of Earthwork Construction

PDHonline Course C284 (8 PDH) Control and Inspection of Earthwork Construction Instructor: George E. Thomas, PE 2012 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDH Course C284 www.PDHonline.org Control and Inspection of Structural Earthwork Construction George E. Thomas, PE A. Principles of Construction Control 1. General. In many types of engineering work, structural materials are manufactured to obtain certain characteristics; their use is prescribed by building codes, handbooks, and codes of practice established by various engineering organizations. However, for earth construction, the common practice is to use material that is available locally rather than specifying that a particular type of material of specific properties be secured. A variety of procedures exists by which earth materials may be satisfactorily incorporated into a structure. When earth is the construction material, personnel in charge of construction control must become familiar with design requirements and must verify that the finished product meets the requirements. Design of earth structures must allow for an inherent range of earth material properties. For maximum economy, tolerance ranges will vary according to available materials, conditions of use, and anticipated methods of construction. A closer relationship is required among the operations of inspection, design, and construction for earthwork than is needed in other engineering disciplines. Construction control of earth structures involves not only practices similar to those normally required for structures using manufactured materials, but also the supervision and inspection normally performed at the manufacturing plant.