Lachlan Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Study Lachlan Shire Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey

2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and Survey 43-51 Cowper Wharf Road September 2013 Woolloomooloo NSW 2011 w: www.mgnsw.org.au t: 61 2 9358 1760 Introduction • This report is presented in two parts: The 2013 NSW Museum & Gallery Sector Census and the 2013 NSW Small to Medium Museum & Gallery Survey. • The data for both studies was collected in the period February to May 2013. • This report presents the first comprehensive survey of the small to medium museum & gallery sector undertaken by Museums & Galleries NSW since 2008 • It is also the first comprehensive census of the museum & gallery sector undertaken since 1999. Images used by permission. Cover images L to R Glasshouse, Port Macquarie; Eden Killer Whale Museum , Eden; Australian Fossil and Mineral Museum, Bathurst; Lighting Ridge Museum Lightning Ridge; Hawkesbury Gallery, Windsor; Newcastle Museum , Newcastle; Bathurst Regional Gallery, Bathurst; Campbelltown arts Centre, Campbelltown, Armidale Aboriginal Keeping place and Cultural Centre, Armidale; Australian Centre for Photography, Paddington; Australian Country Music Hall of Fame, Tamworth; Powerhouse Museum, Tamworth 2 Table of contents Background 5 Objectives 6 Methodology 7 Definitions 9 2013 Museums and Gallery Sector Census Background 13 Results 15 Catergorisation by Practice 17 2013 Small to Medium Museums & Gallery Sector Survey Executive Summary 21 Results 27 Conclusions 75 Appendices 81 3 Acknowledgements Museums & Galleries NSW (M&G NSW) would like to acknowledge and thank: • The organisations and individuals -

Listing and Sitting Arrangements, Nsw Local Court

LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Listing and sitting arrangements of the NSW Local Court Click on the links below to find the listing and sitting arrangements for each court. CHAMBER DAYS – Please note that Chamber Days have been cancelled from August 2020 to March 2021 to allow for the listing of defended work Albion Park Broken Hill Deniliquin Albury Burwood Downing Centre Armidale Byron Bay Dubbo Assessors - Small Claims Camden Dunedoo Ballina Campbelltown Dungog Bankstown Campbelltown Children's Eden Batemans Bay Casino Fairfield Bathurst Central Finley Bega Cessnock Forbes Bellingen Cobar Forster Belmont Coffs Harbour Gilgandra Bidura Children's Court Commonwealth Matters - Glen Innes (Glebe) (see Surry Hills see Downing Centre Gloucester Children’s Court) Condobolin Gosford Blayney Cooma Goulburn Blacktown Coonabarabran Grafton Boggabilla Coonamble Grenfell Bombala Cootamundra Griffith Bourke Corowa Gulgong Brewarrina Cowra Broadmeadow Children's Gundagai Crookwell Court Circuits Gunnedah 1 LISTING AND SITTING ARRANGEMENTS, NSW LOCAL COURT Hay Manly Nyngan Hillston Mid North Coast Children’s Oberon Court Circuit Holbrook Orange Milton Hornsby Parkes Moama Hunter Children’s Court Parramatta Circuit Moree Parramatta Children’s Court Illawarra Children's Court Moruya Peak Hill (Nowra, Pt. Kembla, Moss Moss Vale Vale and Goulburn) Penrith Mt Druitt Inverell Picton Moulamein Junee Port Kembla Mudgee Katoomba Port Macquarie Mullumbimby Kempsey Queanbeyan Mungindi Kiama Quirindi Murrurundi Kurri Kurri Raymond Terrace Murwillumbah -

Outback NSW Regional

TO QUILPIE 485km, A THARGOMINDAH 289km B C D E TO CUNNAMULLA 136km F TO CUNNAMULLA 75km G H I J TO ST GEORGE 44km K Source: © DEPARTMENT OF LANDS Nindigully PANORAMA AVENUE BATHURST 2795 29º00'S Olive Downs 141º00'E 142º00'E www.lands.nsw.gov.au 143º00'E 144º00'E 145º00'E 146º00'E 147º00'E 148º00'E 149º00'E 85 Campground MITCHELL Cameron 61 © Copyright LANDS & Cartoscope Pty Ltd Corner CURRAWINYA Bungunya NAT PK Talwood Dog Fence Dirranbandi (locality) STURT NAT PK Dunwinnie (locality) 0 20 40 60 Boonangar Hungerford Daymar Crossing 405km BRISBANE Kilometres Thallon 75 New QUEENSLAND TO 48km, GOONDIWINDI 80 (locality) 1 Waka England Barringun CULGOA Kunopia 1 Region (locality) FLOODPLAIN 66 NAT PK Boomi Index to adjoining Map Jobs Gate Lake 44 Cartoscope maps Dead Horse 38 Hebel Bokhara Gully Campground CULGOA 19 Tibooburra NAT PK Caloona (locality) 74 Outback Mungindi Dolgelly Mount Wood NSW Map Dubbo River Goodooga Angledool (locality) Bore CORNER 54 Campground Neeworra LEDKNAPPER 40 COUNTRY Region NEW SOUTH WALES (locality) Enngonia NAT RES Weilmoringle STORE Riverina Map 96 Bengerang Check at store for River 122 supply of fuel Region Garah 106 Mungunyah Gundabloui Map (locality) Crossing 44 Milparinka (locality) Fordetail VISIT HISTORIC see Map 11 elec 181 Wanaaring Lednapper Moppin MILPARINKA Lightning Ridge (locality) 79 Crossing Coocoran 103km (locality) 74 Lake 7 Lightning Ridge 30º00'S 76 (locality) Ashley 97 Bore Bath Collymongle 133 TO GOONDIWINDI Birrie (locality) 2 Collerina NARRAN Collarenebri Bullarah 2 (locality) LAKE 36 NOCOLECHE (locality) Salt 71 NAT RES 9 150º00'E NAT RES Pokataroo 38 Lake GWYDIR HWY Grave of 52 MOREE Eliza Kennedy Unsealed roads on 194 (locality) Cumborah 61 Poison Gate Telleraga this map can be difficult (locality) 120km Pincally in wet conditions HWY 82 46 Merrywinebone Swamp 29 Largest Grain (locality) Hollow TO INVERELL 37 98 For detail Silo in Sth. -

Growing Lachlan

Growing Lachlan: Community Driven Place-Based Change FIONA MCKENZIE October 2019 This research was commissioned by Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation and member organisations of the Growing Lachlan Alliance: Lower Lachlan Community Services, Tottenham Welfare Council, and Western NSW Regional Network National Indigenous Australians Agency. It has been undertaken independently by Orange Compass. It is not intended to be used or relied upon by anyone else and is published for general information only. While all efforts have been taken to ensure accuracy, Orange Compass does not accept any duty, liability or responsibility in relation to this Report. Please email: [email protected] with any feedback. CITATION McKenzie, F., 2019. Growing Lachlan: community driven place-based change. Prepared by Orange Compass for Vincent Fairfax Family Foundation, Lower Lachlan Community Services, Tottenham Welfare Council, and Western NSW Regional Network National Indigenous Australians Agency. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 2 ABOUT THIS REPORT 2 ABOUT THE LACHLAN SHIRE 2 ABOUT GROWING LACHLAN 2 ACHIEVEMENTS 6 AN INCREASE IN COMMUNITY PRIORITIES DIRECTING INVESTMENT 7 1. HEARING AND ELEVATING COMMUNITY VIEWS 7 2. WIDER AND MORE EFFECTIVE USE OF DATA 7 3. BRINGING IN EXTRA FUNDING TO THE REGION 8 CHANGES IN HOW THE COMMUNITY WORKS TOGETHER 9 4. BREAKING DOWN LONG STANDING BARRIERS 9 5. JOINING THE DOTS TO FILL SERVICE GAPS 11 6. FINDING COMMON GROUND 12 7. CATALYSING NEW CONVERSATIONS AND ACTIVITIES 12 GROWTH IN THE CAPACITY OF THE COMMUNITY TO DRIVE LONG-TERM CHANGE 13 8. ASKING HARD QUESTIONS AND CHALLENGING LONG HELD PRACTICES 13 9. BUILDING NEW SKILLS IN MANY ORGANISATIONS 13 10. -

NSW HRSI NEWS May 2020

NSWHRSI NEWSLETTER Issue 23 K will do HRSI NSW HRSI NEWS May 2020 A 1965 view of the rarely seen Kelso railway station in western NSW. Leo Kennedy collection NSW HERITAGE RAILWAY STATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE NEWS ISSUE N.23 WELCOME to the 23rd NSWHRSI Australian Rail Maps, Tenterfield newsletter. The objective of this railway museum, Ian C Griggs, Outback Newsletter index newsletter is to inform, educate and Radio 2 Web, Robyne Ridge, Alex WELCOME / MAIN NEWS 1 provide insights about the latest Goodings, Trove, Warren Travis, Barry Trudgett, Alex Avenarius, Brian Blunt, updates, plans and heritage news Chris Gillespie, Brian Hill, Hugh NAMBUCCA RAILWAY STATION 2 relating to Heritage Railway Campbell Stations and Infrastructure (HRSI) NSWGR ANNUAL REPORT 1929-1930 3 across NSW. The news in is separated into 4 core NSW regions TOTTENHAM BRANCH LINE REVIEW 3 – Northern, Western and Southern NSW and Sydney. HAY RAILWAY STATION REVIEW 21 MAIN NEWS NSW NEWS 41 Phil Buckley, NSW HRSI Editor NORTHERN NSW 42 Copyright © 2014 - 2020 NSWHRSI . WESTERN NSW 47 All photos and information remains property of NSWHRSI / Phil Buckley SOUTHERN NSW 58 unless stated to our various contributors / original photographers SYDNEY REGION 63 or donors. YOUR SAY - HERITAGE PHOTOS 74 Credits/Contributors this issue – Rob Williams, Leo Kennedy, Chris Stratton, OTHER NEWS, NEXT ISSUE AND LINKS Brett Leslie, MyTrundle, NSW State 76 Records, Tottenham Historicial Society Nathan Markcrow, Peter McKenzie, Bob Richardson, Warren Banfield, Simon Barber, James Murphy, Page | 1 NSWHRSI NEWSLETTER Issue 23 NAMBUCCA RAILWAY STATION by Rob Williams Some information on the the smaller buildings at the Nambucca Heads railway station.The 2 small buildings located on the northern end were the BGF (Banana Growers Federation) buildings. -

Lachlan River Jemalong Gap to Condobolin Floodplain Management Plan

Floodplain Management Plan Lachlan River (Jemalong Gap to Condobolin) February 2012 The Lachlan River Jemalong Gap to Condobolin Floodplain Management Plan project is indebted to the Lachlan River Floodplain Management Committee, Jemalong Gap to Condobolin, and the landholders who provided input and allowed access to private property. The cooperation received from landholders greatly assisted the collection of data and information on local land use and flooding history. Funding for the Lachlan River Jemalong Gap to Condobolin Floodplain Management Plan was provided by the Commonwealth Natural Disaster Mitigation Program with financial support from the State. Cover photos (clockwise from main photo): Lachlan River downstream of Jemalong Gap, August 1990 (Steve Hogg, NSW Department of Water Resources); Goobang Creek and Lachlan River upstream of Condobolin, August 1990 (Steve Hogg, NSW Department of Water Resources); River red gum woodland near Warroo Bridge (Paul Bendeich, OEH); Goobang Creek (Paul Bendeich, OEH). Disclaimer While every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that this document is correct at the time of printing, the State of New South Wales, its agents and employees, disclaim any and all liability to any person in respect of anything or the consequences of anything done or omitted to be done in reliance upon the whole or any part of this document. © State of NSW, Office of Environment and Heritage, Department of Premier and Cabinet, and Office of Water, Department of Primary Industries. The Office of Environment and Heritage, Office of Water, and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced, for educational or non-commercial use, in whole or in part, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. -

Clean Teq Sunrise Project Road Upgrade and Maintenance Strategy 2020-CTEQ-1220-41PA-0001 27 March 2019

Clean TeQ Sunrise Project Road Upgrade and Maintenance Strategy 2020-CTEQ-1220-41PA-0001 27 March 2019 CONTENTS 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Structure of this Road Upgrade and Maintenance Strategy................................................... 3 2. Scope of Road Inspection Upgrades ............................................................................................. 4 3. Statutory Requirements, Design Standards and Other Applicable Requirements .................... 12 3.1 Statutory Requirements ....................................................................................................... 12 3.2 Design Standards ................................................................................................................. 12 3.3 Road Safety Audits ............................................................................................................... 12 4. Existing Road Description and Baseline Data ............................................................................ 14 4.1 Description of Existing Roads to be Upgraded .................................................................... 14 4.2 Historic Traffic Volumes and Capacity ................................................................................. 15 5. Project Traffic -

NSW Trainlink Regional Train and Coach Services Connect More Than 365 Destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland

Go directly to the timetable Dubbo Tomingley Peak Hill Alectown Central West Euabalong West Condobolin Parkes Orange Town Forbes Euabalong Bathurst Cudal Central Tablelands Lake Cargelligo Canowindra Sydney (Central) Tullibigeal Campbelltown Ungarie Wollongong Cowra Mittagong Lower West Grenfell Dapto West Wyalong Bowral BurrawangRobertson Koorawatha Albion Park Wyalong Moss Vale Bendick Murrell Barmedman Southern Tablelands Illawarra Bundanoon Young Exeter Goulburn Harden Yass Junction Gunning Griffith Yenda Binya BarellanArdlethanBeckomAriah Park Temora Stockinbingal Wallendbeen Leeton Town Cootamundra Galong Sunraysia Yanco BinalongBowning Yass Town ACT Tarago Muttama Harden Town TASMAN SEA Whitton BurongaEuston BalranaldHay Carrathool Darlington Leeton NarranderaGrong GrongMatong Ganmain Coolamon Junee Coolac Murrumbateman turnoff Point Canberra Queanbeyan Gundagai Bungendore Jervis Bay Mildura Canberra Civic Tumut Queanbeyan Bus Interchange NEW SOUTH WALES Tumblong Adelong Robinvale Jerilderie Urana Lockhart Wagga Wondalga Canberra John James Hospital Wagga Batlow VICTORIA Deniliquin Blighty Finley Berrigan Riverina Canberra Hospital The Rock Laurel Hill Batemans Bay NEW SOUTH WALES Michelago Mathoura Tocumwal Henty Tumbarumba MulwalaCorowa Howlong Culcairn Snowy Mountains South Coast Moama Barooga Bredbo Albury Echuca South West Slopes Cooma Wangaratta Berridale Cobram Nimmitabel Bemboka Yarrawonga Benalla Jindabyne Bega Dalgety Wolumla Merimbula VICTORIA Bibbenluke Pambula Seymour Bombala Eden Twofold Bay Broadmeadows Melbourne (Southern Cross) Port Phillip Bay BASS STRAIT Effective from 25 October 2020 Copyright © 2020 Transport for NSW Your Regional train and coach timetable NSW TrainLink Regional train and coach services connect more than 365 destinations in NSW, ACT, Victoria and Queensland. How to use this timetable This timetable provides a snapshot of service information in 24-hour time (e.g. 5am = 05:00, 5pm = 17:00). Information contained in this timetable is subject to change without notice. -

Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: an Economic Analysis

Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: An Economic Analysis Salahadin A. Khairo John D. Mullen Ronald B. Hacker Dean A. Patton Economic Research Report No. 31 Farming Systems in the Pastoral Zone of NSW: An Economic Analysis Salahadin Khairo Economist, Pastures and Rangelands NSW DPI, Trangie John Mullen Research Leader, Economics Research NSW DPI, Orange Ron Hacker Research Leader, Pastures and Rangelands NSW DPI, Trangie Dean Patton Manager Condobolin Agricultural Research Centre March 2008 Economic Research Report No. 31 ii © NSW DPI 2008 This publication is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owner. Neither may information be stored electronically in any way whatever without such permission. ABSTRACT A ‘broad brush’ picture of farming in the pastoral zone of NSW is presented in this report. The pastoral zone of NSW is characterised by wide variations in climatic conditions, soil type and vegetation species. Hence representative faming system analysis was conducted for three sub-regions - the Upper Darling, the Murray-Darling and Far West. The regions were defined and described in terms of their resources, climate and the nature of agriculture. The main enterprises that farmers choose between were described and whole farm budgets and statements of assets and liabilities for the representative farms were developed. The representative farm models were used to compare traditional Merino based sheep enterprises with alternative sheep enterprises where meat was an important source of income. We found that the farming systems that have evolved in these areas are well suited to their respective environments and that the economic incentives to switch to more meat focussed sheep enterprises were not strong. -

TAA 0319-2009 Please Note## Heritage Services Are to Be Managed As Passenger Trains, in Accordance with Network Management Principles

TRAIN ALTERATION ADVICE NO: TAA 0319-2009 Please Note## Heritage Services are to be managed as passenger trains, in accordance with Network Management Principles DUE TO THE FOLLOWING: THE RAIL MOTOR SOCIETY “PARKES RAIL MOTOR TOUR” 5th –9th JUNE 2009 THE FOLLOWING TIMETABLES WILL APPLY: NR70 on Fri 05/06/2009 will depart Paterson 1200, pass Mindaribba 1207, Telarah 1213, Maitland 1216, Thornton 1228, Sandgate 1240, Warabrook 1241, Islington Junction 1245, thence as tabled by RailCorp. WR71 on Sat 06/06/2009 will run as tabled by RailCorp to pass Wallerawang 1109, Tarana 1133, Kelso 1205, Bathurst 1210, arrive Blayney 1311, lunch, depart 1425, pass Polona 1436, Spring Hill 1445, Orange East Fork Jct 1455, arrive Orange 1500, a, depart 1515, pass Molong 1544, Manildra 1606, Bumberry 1630, arrive Parkes 1702, detrain passengers, stable. Final WR73 on Sun 07/06/2009 will depart Parkes 0830, pass Goobang Jct 0835, Gunningbland 0853, arrive Bogan Gate 0903, x, depart 0922, pass Yarrabandai 0939, Ootha 0949, Derriwong 0957, Condobolin 1010, Kiacatoo 1034, Euabalong West 1104, Matakana 1136, arrive Roto 1207, form WR74. WR74 on Sun 07/06/2009 will depart Roto 1222, pass Matakana 1229, arrive Euabalong West 1237, lunch stop, depart 1400, pass Kiacatoo 1437, Condobolin 1506, Derriwong 1524, Ootha 1535, Yarrabandai 1547, Bogan Gate 1605, Gunningbland 1619, SCT Parkes Junction 1641, Goobang Jct 1646, arrive Parkes 1650, detrain passengers, stable. WR75 on Mon 08/06/2009 will depart Parkes 0830, arrive Forbes 0902, a, g, depart 0932, arrive Wirrinya 1014, g, depart 1019, arrive Caragabal 1039, g, depart 1044, arrive Bribbaree 1119, g, depart 1124, arrive Stockinbingal 1210, g, depart 1215, arrive Cootamundra West 1228, g, depart 1238, arrive Cootamundra 1240, lunch stop, form SR76. -

Development Control Plan 2018

Development Control Plan 2018 LACHLAN SHIRE COUNCIL This page has been intentionally left blank. Lachlan Development Control Plan 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 NAME OF THIS PLAN ................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 PURPOSE OF THIS PLAN ............................................................................................................. 3 1.3 LAND TO WHICH THIS PLAN APPLIES ............................................................................................ 3 1.4 FORMAT OF THIS PLAN ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 THE DEVELOPMENT APPLICATION PROCESS ................................................................................. 4 1.6 APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS ..................................................................................................... 5 1.7 BASIX ...................................................................................................................................... 7 1.8 DEFINITIONS .............................................................................................................................. 8 1.9 SAVINGS PROVISIONS ................................................................................................................ 8 2. SUBDIVISION ................................................................................................................................ -

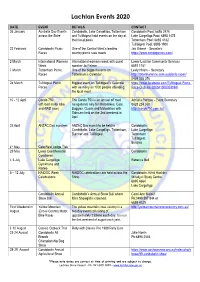

Lachlan Events 2020

Lachlan Events 2020 DATE EVENT DETAILS CONTACT 26 January Australia Day Events Condobolin, Lake Cargelligo, Tottenham Condobolin Pool: 6895 2475 across the Shire and Tullibigeal hold events on the day at Lake Cargelligo Pool: 6898 1475 their local pools Tottenham Pool: 6892 4142 Tullibigeal Pool: 6895 1900 22 February Condobolin Picnic One of the Central West's leading Joy Gibson - Secretary Races country picnic race meets https://www.condopicnics.com/ 2 March International Womens International womens week with guest Lower Lachlan Community Services Week speaker Jo Palmer 6892 1151 7 March Tottenham Picnic One of the biggest events on Lesly Hillam – Secretary Races Tottenham’s Calendar http://tottenhamnsw.com.au/picnic-races/ 0429 028 376 28 March Tullibigeal Picnic Biggest event on Tullibigeal’s Calendar https://www.facebook.com/Tullibigeal-Picnic- Races with as many as 1000 people attending Race-Club-Inc-200341300053194/ the local meet. 10 - 12 April Condo 750 The Condo 750 is an annual off road Adriana Pangas - Event Secretary (off road motor bike navigational rally for Motorbikes, Cars, 0428 234 350 and 4WD race) Buggies, Quads and Motorbikes with http://condo750.com.au/ Sidecars held on the 2nd weekend in April. 25 April ANZAC Day marches ANZAC Day march to be held in Condobolin: Condobolin, Lake Cargelligo, Tottenham, Lake Cargelligo: Burcher and Tullibigeal. Tottenham Tullibigeal: Burcher 4th May CareWest Lodge Trek 29 May Lewis Coe Memorial Condobolin Coroboree 4-5 July Lake Cargelligo Rebecca Bell Gymkhana and Rodeo 5 – 12 July NAIDOC Week NAIDOC celebrations are held across the Condobolin: Kristi Hoskins Celebrations Shire. Wiradjuri Study Centre 6895 4664 Lake Cargelligo: Condobolin Annual Condobolin’s Annual Show Ball where Carol-Ann Malouf Show Ball Miss Showgirl is crowned.