Problems of Transmedia Storytelling in Game of Thrones Rebecca L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brewery Ommegang Cooperstown, New York

Volume 17 Issue 10 Brewery Ommegang Cooperstown, New York Valar Dohaeris We’ve long been fans of Brewery artisans of medieval Brussels came of Belgian kriek (cherry beer) added. Ommegang in upstate New together to stage a celebration Ommegang’s Witte Wheat Ale was added York, which has been making for the Holy Roman Emperor King in 2004 and became their first beer amazing Belgian-style beers Charles V and his Royal Court. The packaged into kegs, and the brewery’s since 1996. Ommegang became annual gathering would be known Belgium Comes to Cooperstown festival the first farmhouse brewery in as the “Ommegang” (meaning was first held in July of that same year. America in 100+ years, created ‘walking about’ and ‘coming Combining beer tastings, local foods, when the Belgian breweries together’) and continues as the camping, and music at Ommegang’s Duvel Moortgat, Affligem, and Brussels Ommegang Festival to scenic farmhouse location proved to Scaldis joined with importers/ this day. be a big hit, with over 50,000 people entrepreneurs Don Feinberg participating in the annual event over the and Wendy Littlefield to Brewery Ommegang following 15 years. create a Belgian-style launched its first beer in brewery in Cooperstown, 1997 with Ommegang The brewery’s done a ton of cool New York. They located Abbey Dubbel, a hefty projects over the years. There’s a the brewery on an old Trappist-style dark ale natural amphitheater that sits behind 140-acre hop farm in with spices that was Ommegang, and in 2011 the brewery the Susquehanna River packaged in 750mL valley, in a region once bottles—all pretty out (Continued on reverse page) known as Nova Belgium. -

Download 1St Season of Game of Thrones Free Game of Thrones, Season 1

download 1st season of game of thrones free Game of Thrones, Season 1. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. The PlayOn Blog. Record All 8 Seasons Game of Thrones | List of Game of Thrones Episodes And Running Times. Here at PlayOn, we thought. wouldn't it be great if we made it easy for you to download the Game of Thrones series to your iPad, tablet, or computer so you can do a whole lot of binge watching? With the PlayOn Cloud streaming DVR app on your phone or tablet and the Game of Thrones Recording Credits Pack , you'll be able to do just that, AND you can do it offline. That's right, offline . -

Zoological Nomenclature of Ice and Fire

Zoological Nomenclature of Ice and Fire Evangelos Vlachos CONICET & Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio, Trelew, Chubut, Argentina. Email: [email protected] Valar gūrēñis — All men must learn probably sounded differently in the Common Tongue. The diversity of the World of Ice and Fire Back to our world, following the pioneering (Westeros, Essos and the other continents work of C. Linnaeus in 1758 the need of a stable combined) is remarkable. All kinds of species of and universal system of biological animals and plants are known, including some nomenclature became necessary. Since then, a mythical creatures. The purpose of this set of rules has been created, revised, used and contribution is to provide a system of applied to Zoological Nomenclature, forming nomenclature for the most important animal the so-called International Code of Zoological species from the World of Ice and Fire. This Nomenclature (ICZN, or simply ‘the Code’). The new system is based on the High Valyrian latest edition was published in 1999, and some language, and aims to provide a set of names parts of the Code have been recently (2012) that can be applied to the various species of life amended to include names and acts published that survived, or even became extinct, in this in electronic-only journals. world. I will briefly present the main features of The World of Ice and Fire is a fictional this system of nomenclature for those not world. Although most of the wild and entirely familiar with it. The backbone concept domesticated animals are the same or similar of nomenclature is the binomen: each species to our own, there several animals that are name is formed by two components, the genus unique to it. -

Final Draft Thesis Corrected

REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !1 Redefining Masculinity through Disability in HBO’s Game of Thrones A Capstone Thesis Submitted to Southern Utah University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Professional Communication April 2016 By Amanda J. Dearman Capstone Committee: Dr. Kevin A. Stein, Ph.D., Chair Dr. Arthur Challis, Ed.D. Dr. Matthew H. Barton, Ph.D. Running head: REDEFINING MASCULINITY IN GAME OF THRONES !3 Acknowledgements I have been blessed with the support of a number of number of people, all of whom I wish to extend my gratitude. The completion of my Master’s degree is an important milestone in my academic career, and I could not have finished this process without the encouragement and faith of those I looked toward for support. Dr. Kevin Stein, I can’t thank you enough for your commitment as not only my thesis chair, but as a professor and colleague who inspired many of my creative endeavors. Under your guidance I discovered my love for popular culture studies and, as a result, my voice in critical scholarship. Dr. Art Challis and Dr. Matthew Barton, thank you both for lending your insight and time to my committee. I greatly appreciate your guidance in both the completion of my Master’s degree and the start of my future academic career. Your support has been invaluable. Thank you. To my family and friends, thank you for your endless love and encouragement. Whether it was reading my drafts or listening to me endlessly ramble on about my theories, your dedication and participation in this accomplishment is equal to that of my own. -

Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of York As Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow

Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Memòria del Treball de Fi de Grau Rewriting Historical Characters: Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of York as Daenerys Targaryen and Jon Snow Maria Antònia Llabrés Font Grau d'Estudis Anglesos Any acadèmic 2018-19 DNI de l’alumne:43472881Y Treball tutelat per José Igor Prieto Arranz Departament de Filologia Espanyola, Moderna i Clàssica S'autoritza la Universitat a incloure aquest treball en el Repositori Autor Tutor Institucional per a la seva consulta en accés obert i difusió en línia, Sí No Sí No amb finalitats exclusivament acadèmiques i d'investigació Paraules clau del treball: reversal gender roles, historical discourse, power, recognition, fantasy Abstract This essay examines the relationship between the historical figures Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and the fictional characters Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen from the popular TV series Game of Thrones. Through the analysis of the similarities between their lives, this project attempts to prove how both fictional characters are based and influenced by Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. Moreover, there is very little previous literature about the life of Elizabeth of York, obscuring and undermining her important role in putting an end to the Wars of the Roses. Thus, besides proving the relationship between these historical characters and the fictional ones, the aim of this paper is also to emphasise the historical importance given to Elizabeth of York in Game of Thrones by means of using her as a main source of inspiration for two of the most important an relevant characters of the series. As a result, this work also intends to prove how Game of Thrones demolishes gender boundaries by using characteristics of both Henry VII and Elizabeth of York to shape the characters of Jon Snow and Daenerys Targaryen. -

Style and World-Building in George R. R. Martin's a Song of Ice and Fire

HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO Style and World-Building in George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire Jaru Hirsso 013028752 Pro Gradu Spring 2015 Department of Modern Languages / English University of Helsinki Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos – Institution – Department Humanistinen tiedekunta Nykykielten laitos Tekijä – Författare – Author Jaru Tapio Hirsso Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Style and World-Building in George R. R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Englantilainen filologia Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and Sivumäärä – Sidoantal – Number of pages year Pro gradu Huhtikuu 2015 82 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielmani käsittelee kielellisen tyylin ja maailmanrakennuksen suhdetta George R. R. Martinin fantasiakirjasarjassa A Song of Ice and Fire (suom. Tulen ja jään laulu). Tarkoituksena on erityisesti selvittää, miten kirjojen kieli poikkeaa tavanomaisesta englannin kielestä, ja miten kielen poikkeavat muodot puolestaan toimivat keskiaikaisen fantasiamaailman rakennuspalikoina. Susan Mandalan (2010) mukaan kielellinen tyyli on jäänyt lapsipuolen asemaan tieteis- ja fantasiakirjallisuuden tutkimuksessa: kieltä on lähes poikkeuksetta pidetty tavanomaisena tai heikkona, ja sen roolia on myös vähätelty. Mandalan mukaan tällaiset käsitykset ovat perusteettomina, ja hänen mielestään toimiva tyyli on todella tärkeässä roolissa nimenomaan näissä genreissä, sillä se on oleellinen osa muun muassa uskottavien vaihtoehtoismaailmojen luomista. Kirjojen maailma on keskiaikainen, -

Carolyne Larrington

Winter is coming Carolyne Larrington Winter is coming LES RACINES MÉDIÉVALES DE GAME OF THRONES Traduit de l’anglais par Antoine Bourguilleau ISBN 978‑2‑3793‑3049‑0 Dépôt légal – 1re édition : 2019, avril © Passés Composés / Humensis, 2019 170 bis, boulevard du Montparnasse, 75014 Paris Le code de la propriété intellectuelle n’autorise que « les copies ou reproductions stric‑ tement réservées à l’usage privé du copiste et non destinées à une utilisation collec‑ tive » [article L. 122‑5] ; il autorise également les courtes citations effectuées dans un but d’exemple ou d’illustration. En revanche « toute représentation ou reproduction intégrale ou partielle, sans le consentement de l’auteur ou de ses ayants droit ou ayants cause, est illicite » [article L. 122‑4]. La loi 95‑4 du 3 janvier 1994 a confié au C.F.C. (Centre français de l’exploitation du droit de copie, 20, rue des Grands Augustins, 75006 Paris), l’exclusivité de la gestion du droit de reprographie. Toute photocopie d’oeuvres protégées, exécutée sans son accord préalable, constitue une contrefaçon sanctionnée par les articles 425 et suivants du Code pénal. Sommaire Liste des abréviations ....................................................... 9 Préface ................................................................................ 15 Introduction ....................................................................... 19 Chapitre 1. Le Centre ........................................................ 31 Chapitre 2. Le Nord ......................................................... -

Game of Thrones Season 3 Episode 10 Download Free Game of Thrones, Season 3

game of thrones season 3 episode 10 download free Game of Thrones, Season 3. Game of Thrones is an American fantasy drama television series created for HBO by David Benioff and D. B. Weiss. It is an adaptation of A Song of Ice and Fire, George R. R. Martin's series of fantasy novels, the first of which is titled A Game of Thrones. The series, set on the fictional continents of Westeros and Essos at the end of a decade-long summer, interweaves several plot lines. The first follows the members of several noble houses in a civil war for the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms; the second covers the rising threat of the impending winter and the mythical creatures of the North; the third chronicles the attempts of the exiled last scion of the realm's deposed dynasty to reclaim the throne. Through its morally ambiguous characters, the series explores the issues of social hierarchy, religion, loyalty, corruption, sexuality, civil war, crime, and punishment. Game of Thrones – Season 3 Complete. The third season of the fantasy drama television series Game of Thrones premiered in the United States on HBO on March 31, 2013, and concluded on June 9, 2013. It was broadcast on Sunday at 9:00 pm in the United States, consisting of 10 episodes, each running approximately 50–60 minutes. [1] The season is based roughly on the first half of A Storm of Swords (the third of the A Song of Ice and Fire novels by George R. R. Martin, of which the series is an adaptation). -

2013 HPA Awards Announce Craft Category Nominees and Special Award Winners

Sponsors 2013 HPA Awards Announce Craft Category Nominees and Special Award Winners HPA Engineering Excellence Award Sponsor Judges Award for Creativity & Innovation and Engineering Excellence Winners Revealed BRONZE September 4, 2013 (Los Angeles, CA) Today in a special on-line press event, the Hollywood Post Alliance® - the trade association for the post production community - announced the nominees for the craft categories of the 8th Annual HPA Awards and winners of several special awards. The HPA Awards honor SUPPORTING excellence in post production and bring recognition to the achievements of individuals and companies who are engaged in significant and revolutionary work in post production. The HPA Awards will take place on the evening of November 7th, 2013 at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, CA. The number of entries in all categories and for special awards topped every year to date for this year's honors. The nominees in the 12 craft categories were chosen from a field of talented and innovative entries in color grading, editing, sound, and visual effects for motion pictures, commercials and television. Nominees for the 2013 HPA Awards are: Outstanding Color Grading – Feature Film “Star Trek Into Darkness” Stefan Sonnenfeld // Company 3 “Oblivion” Mike Sowa // Technicolor “Anna Karenina” Adam Glasman // Company 3 (more) 846 S. Broadway, Suite 601 • Los Angeles, CA 90014 • Ph: 213-614-0860 • Fax: 213-614-0890 • www.hpaawards.net Outstanding Color Grading – Feature Film (continued) “Life of Pi” David Cole // Technicolor -

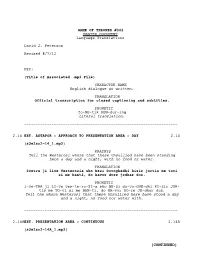

Master Dialogue for Game of Thrones Seasons 3 Through 8

GAME OF THRONES #302 MASTER DOCUMENT Language Translations David J. Peterson Revised 8/7/12 KEY: (Title of Associated .mp3 File) CHARACTER NAME English dialogue as written. TRANSLATION Official transcription for closed captioning and subtitles. PHONETIC fo-NE-tik REN-dur-ing Literal translation. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2.14 EXT. ASTAPOR - APPROACH TO PRESENTATION AREA - DAY 2.14 (s3e2sc2-14_1.mp3) KRAZNYS Tell the Westerosi whore that these Unsullied have been standing here a day and a night, with no food or water. TRANSLATION Ivetra ji live Vesterozia sko bezi Dovoghedhi kizir jortis me tovi si me banti, do havor dore jedhar dos. PHONETIC i-ve-TRA ji LI-ve ves-te-ro-ZI-a sko BE-zi do-vo-GHE-dhi KI-zir JOR- tis me TO-vi si me BAN-ti, do HA-vor DO-re JE-dhar dos. Tell the whore Westerosi that these Unsullied here have stood a day and a night, no food nor water with. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2.14AEXT. PRESENTATION AREA - CONTINUOUS 2.14A (s3e2sc2-14A_1.mp3) (CONTINUED) GAME OF THRONES Master Dialogues (Season 3-8) 04/11/20 2. 2.14ACONTINUED: 2.14A KRAZNYS Tell the silver-haired slut they will each stand until they drop. Such is their obedience. TRANSLATION Ivetra ji rene eji oghrar gelinko sko majorozlivis eva ruhilis (ERROR: Should be vrogilis). Vagizi poja pihtenkave sa. PHONETIC i-ve-TRA ji RE-ne E-ji OGH-rar ge-LIN-ko sko ma-jo-roz-LI-vis E-va ru-HI-lis. va-GI-zi PO-ja pih-ten-KA-ve sa. Tell the slut with-the hair of silver that they will stand until they drop. -

Binge Bootcamp

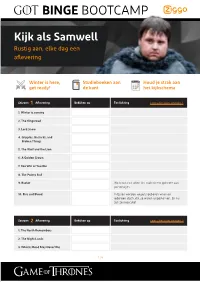

BINGE BOOTCAMP Kijk als Samwell Rustig aan, elke dag een aflevering Winter is here, Studieboeken aan Houd je strak aan get ready! de kant het kijkschema Seizoen1 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 1 1. Winter is coming 2. The Kingsroad 3. Lord Snow 4. Cripples, Bastards, and Broken Things 5. The Wolf and the Lion 6. A Golden Crown 7. You Win or You Die 8. The Pointy End 9. Baelor We leren een wijze les: raak niet te gehecht aan personages. 10. Fire and Blood In Essos worden wezens geboren waarvan iedereen dacht dat ze waren uitgestorven. En nu zijn ze nog cute! Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 1. The North Remembers 2. The Night Lands 3. What is Dead May Never Die 1 /4 BINGE BOOTCAMP Seizoen2 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 2 4. Garden of Bones 5. The Ghost of Harranhal 6. The Old Gods and the New 7. A Man Without Honor 8. The Prince of Winterfell 9. Blackwater King’s Landing, de hoofdstad van de Seven Kingsdoms, wordt aangevallen. Wat volgt is episch. 10. Valar Morghulis Seizoen3 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 3 1. Valar Dohaeris 2. Dark Wings, Dark Words 3. Walk of Punishment 4. And Now His Watch is 5. Kissed by Fire 6. The Climb 7. The Bear and the Maiden 8. Second Sons 9. The Rains of Castamere 10. Mhysa Seizoen4 Aflevering Bekijken op Toelichting Lees alles over seizoen 4 1. Two Swords 2. The Lion and the Rose Wraak is zoet! 3. -

A Dance with Old Tongues (PDF)

valar morghulis, valar dohaeris A Dance with Old Tongues valar morghulis valar dohaeris Carlos Quiles Version: 1.2 (draft) 21 April 2019 Images © 2019 by Carlos Quiles [email protected] Images and updates: <https://indo-european.eu/maps/game-of-thrones/> This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/> or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Text All materials using or referring to George R. R. Martin’s publications, or the Known World by the publisher/s, and/or companies with rights over such works or materials belong to the copyright holder/s. Texts or images copied or referenced from A Song of Ice and Fire Wiki and other blogs retain their original licenses (see each reference for details). Materials otherwise not subject to copyright are released under the same license as the images. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/> or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... 3 Foreword ...................................................................................................................... 5 Conventions ................................................................................................................