PLD 2010 Sc 612 at Page 618

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

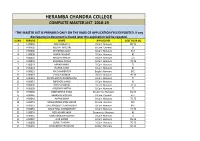

Heramba Chandra College Complete Master List 2018-19

HERAMBA CHANDRA COLLEGE COMPLETE MASTER LIST 2018-19 *THE MASTER LIST IS PREPARED ONLY ON THE BASIS OF APPLICATION FEES DEPOSITED. If any discrepancy in document is found later the application will be rejected. SL NO. FORM ID NAME APPLIED FOR BEST FOUR (%) 1 H00001 RIBHU BAGCHI B.Com Honours 80.75 2 H00002 VEDANT NAGORI B.Com. General 58 3 H00006 INTEKHAB ALAM B.Com Honours 91.5 4 H00009 NABIN BHAGAT B.Com Honours 85 5 H00016 NIKESH CHHETRI B.Com Honours 72.5 6 H00018 MONISHA PANJA B.Com Honours 78.25 7 H00019 ARNAB NANDI B.Com Honours 79 8 H00021 RUPNIL SAHA B.Com Honours 84 9 H00025 KAUSHAMBI ROY English Honours 80.5 10 H00027 LYDIA S KUMAR B.Com Honours 70.75 11 H00031 PUNYA BRATO SANKAR DAS B.Com Honours 77 12 H00035 SHREYOSI NANDI B.Com Honours 90 13 H00036 ROHIT MONDAL B.Com Honours 76.75 14 H00038 ANUBHAV MITRA B.Com Honours 73 15 H00040 SIDDHARTHA SHAW Economics Honours 81.75 16 H00045 SAHANUR HOSSAIN B.Com. General 61.5 17 H00048 ARPAN SAHA B.Com Honours 75.75 18 H00051 MOHAMMAD MOHIUDDIN B.Com. General 58.5 19 H00052 SHOURADEEP CHAKRABORTY B.Com Honours 89.5 20 H00053 IMAN PAUL CHOWDHURY B.Com Honours 74.75 21 H00054 NEELANJAN SAHA Economics Honours 89 22 H00055 ASMIT BANDOPADHYAY B.Com Honours 74 23 H00057 ALIK GAYEN B.Com Honours 85.25 24 H00058 SURAJ THADANI B.Com Honours 70.75 25 H00059 RAJSUBHRA PRAMANIC English Honours 66.25 26 H00060 JAY PRAKASH TIWARY B.Com Honours 89.75 27 H00063 TAPO BRATA SANKAR DAS B.Com Honours 71 28 H00065 PRATIK SEN B.Com Honours 82 29 H00068 AKASH KUMAR SINGH B.Com Honours 73 30 H00073 MAUSAMI SINGH B.Com Honours 83.5 31 H00076 NISSAN DHAR B.Com Honours 80 32 H00078 SUBHAJIT CHAKRABORTY B.Com Honours 78.25 33 H00080 ADARSH ANAND B.Com. -

Attorney-General of Pakistan - a Brief Overview Umair Ghori

Bond Law Review Volume 23 | Issue 2 Article 5 2011 Attorney-General of Pakistan - A brief overview Umair Ghori Follow this and additional works at: http://epublications.bond.edu.au/blr This Article is brought to you by the Faculty of Law at ePublications@bond. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bond Law Review by an authorized administrator of ePublications@bond. For more information, please contact Bond University's Repository Coordinator. Attorney-General of Pakistan - A brief overview Abstract The legal system of Pakistan represents a fusion of the Shariah law and common law systems. Traditionally, the Pakistani legal system adapted the pre-1947 colonial law for local use. Amendments to these colonial laws, in particular inspired by the Islamic traditions, have been interspersed in intervals. As a result, the Pakistan legal system retains fundamental common law doctrines (such as binding precedent and delegated legislation) while gradually integrating laws of Islamic origin within the existing common law framework. However, Pakistan’s legal system is far from being a complete mirror of the English legal system. One such major distinction is that there is no division within the legal profession into barristers and solicitors. This has meant, amongst other things, that the chief legal officer representing the Federation of Pakistan (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Federation’) is the Attorney-General of Pakistan and that there is no comparable office of Solicitor- General in Pakistan as in other common law jurisdictions. This article provides a brief overview of the Attorney-General of Pakistan and the importance of the office to Pakistan as a developing country and a maturing legal system in its own right. -

Université De Montréal /7 //F Ç /1 L7iq/5-( Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema Ofthe 1990S Par Tania

/7 //f Ç /1 l7Iq/5-( Université de Montréal Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema ofthe 1990s par Tania Ahmad Département d’anthropologie Faculté des arts et sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.Sc. en programme de la maîtrise août 2003 © Tania Ahrnad 2003 n q Université (1111 de Montréal Direction des bibliothèques AVIS L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse. L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur. Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant. NOTICE The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexclusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes. The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document. -

The Trial and Execution of Bhutto by J. C. Batra

THE TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF BHUTTO J. C. BATRA Barrister-at-law Consulting Editor Danial Latifi Barrister-at-law (Senior Advocate, Supreme Court) Reproduced by Sani Hussain Panhwar The Trial and Execution of Bhutto; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 1 Dedicated to the people of Pakistan The Trial and Execution of Bhutto; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 2 Contents 1. Political Turmoil. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 2. Behind the bars. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 3. More Accusations. .. .. .. .. .. .. 67 4. Lahore High Court Judgment. .. .. .. .. 73 5. Reactions and Clemency Appeals .. .. .. .. 98 6. The Final Judgment. .. .. .. .. .. .. 106 7. Renewed Pleas to Save Bhutto. .. .. .. .. 158 8. The Final Review. .. .. .. .. .. .. 164 9. Historic Hanging. .. .. .. .. .. .. 173 The Trial and Execution of Bhutto; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 3 Political Turmoil Suffering is one very long moment. We cannot divide it by seasons. We can only record its moods and chronicle their return. Oscar Wilde Destiny is not always kind. Many great statesmen, soldiers and saints have been its victims and their worth ridiculed. Though I do not believe in Astrology, the "March link" on Pakistan is astounding. Astrologers have always forecast the month of March as being ill-starred for the country. It was on March 23, 1940 that the Muslim League finally committed itself to the two-nation theory and adopted the Lahore Resolution calling for the establishment of Pakistan as a separate State. In March, 1947 communal riots broke up in the Punjab which further led to the division of the Punjab and Bengal. In March, 1953 the Martial Law was imposed in Pakistan for the first time in the wake of the anti-Qadian riots. -

The Mirage of Power, by Mubashir Hasan

The Mirage of Power AN ENQUIRY INTO THE BHUTTO YEARS 1971-1977 BY MUBASHIR HASAN Reproduced By: Sani H. Panhwar Member Sindh Council PPP. CONTENTS About the Author .. .. .. .. .. .. i Preface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ii Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. .. v 1. The Dramatic Takeover .. .. .. .. .. 1 2. State of the Nation .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 3. Meeting the Challenges (1) .. .. .. .. 22 4. Meeting the Challenges (2) .. .. .. .. 43 5. Restructuring the Economy (1) .. .. .. .. 64 6. Restructuring the Economy (2) .. .. .. .. 85 7. Accords and Discords .. .. .. .. 100 8. All Not Well .. .. .. .. .. .. 120 9. Feeling Free .. .. .. .. .. .. 148 10. The Year of Change .. .. .. .. .. 167 11. All Power to the Establishment .. .. .. .. 187 12. The Losing Battle .. .. .. .. .. .. 199 13. The Battle Lost .. .. .. .. .. .. 209 14. The Economic Legacy .. .. .. .. .. 222 Appendices .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 261 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Mubashir Hasan is a well known figure in both academic and political circles in Pakistan. A Ph.D. in civil engineering, he served as an irrigation engineer and taught at the engineering university at Lahore. The author's formal entry into politics took place in 1967 when the founding convention of the Pakistan Peoples' Party was held at his residence. He was elected a member of the National Assembly of Pakistan in 1970 and served as Finance Minister in the late Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's Cabinet from 1971-1974. In 1975, he was elected Secretary General of the PPP. Following the promulgation of martial law in 1977, the author was jailed for his political beliefs. Dr. Hasan has written three books, numerous articles, and has spoken extensively on social, economic and political subjects: 2001, Birds of the Indus, (Mubashir Hasan, Tom J. -

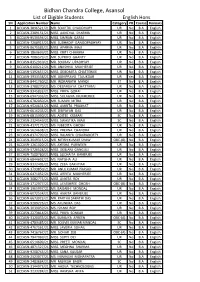

English Hons. SN Application Number Name Category PH Course Honours 1 BCCASN-3896521/21 MR

Bidhan Chandra College, Asansol List of Eligible Students English Hons. SN Application Number Name Category PH Course Honours 1 BCCASN-3896521/21 MR. SOUPTIK CHAUDHURY UR No B.A English 2 BCCASN-2389151/21 MISS. AANCHAL SHARMA UR No B.A English 3 BCCASN-9539594/21 MISS. SIMRAN GARAI UR No B.A English 4 BCCASN-7268915/21 MR. SUBHADIP GANGOPADHYAY UR No B.A English 5 BCCASN-8675585/21 MISS. APARNA MAJI UR No B.A English 6 BCCASN-1860639/21 MISS. KRITI CHHABRA UR No B.A English 7 BCCASN-7086579/21 MR. SUPRIYO GHANTY UR No B.A English 8 BCCASN-8352910/21 MR. SOURAV UPADHYAY UR No B.A English 9 BCCASN-6100212/21 MR. ANJISHNU MUKHERJEE UR No B.A English 10 BCCASN-5392657/21 MISS. DEBOMITA CHATTERJEE UR No B.A English 11 BCCASN-3933538/21 MR. AGNIPRAVO TALUKDAR UR Yes B.A English 12 BCCASN-8441760/21 MR. INDRANATH MANDI ST No B.A English 13 BCCASN-3788270/21 MS. DEBARGHYA CHATTARAJ UR No B.A English 14 BCCASN-9345833/21 MISS. PRIYA GORAI UR No B.A English 15 BCCASN-6947333/21 MISS. SULAGNA MUKHERJEE UR No B.A English 16 BCCASN-6782050/21 MR. SUMAN MITRA UR No B.A English 17 BCCASN-9520631/21 MISS. AMRITA PRABHAT UR No B.A English 18 BCCASN-6616235/21 MR. DIBYAYAN DAS UR No B.A English 19 BCCASN-6815390/21 MS. ADITEE KUMARI SC No B.A English 20 BCCASN-2324549/21 MISS. SWASTIKA MAJI SC No B.A English 21 BCCASN-4177175/21 MS. -

Witness to Splendour Splendour to Witness Splendour

WITNESS TO WITNESS TO SPLENDOUR SPLENDOUR Z.A. Bhutto Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar Member Sindh Council PPP CHAPTER ONE: THE FIRST DAY Mr. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: My Lords, I know that according to protocol and the ethics of the court, I am not supposed to express my thanks and gratitude to this honorable court for permitting me to appear before you this morning. Nevertheless, according to the social conditions of the country, and in Rome do as the Romans do, I am very thankful to you for allowing me this opportunity. In my application to Your Lordships on the 4th of December, I submitted that I would like to present before this honorable court my point of view because not only my life as life of an individual is involved but because, according to my objective appreciation, far more is at stake. My reputation, the honor of my family, my political career and above fall the future of Pakistan itself is involved. This is my view; it may be a mistaken view but it is an honest and sincere view. I am not trying to dramatize or exaggerate. In my application, I said that in the interest of justice I would appreciate that kind favorable consideration be given to my application. On the 5th of December, Your Lordships were kind enough to pass an order stating that Your Lordships had decided at the inception that if needed I should make an appearance before this honorable court in the course of this appeal. Your Lordships reiterated the observation made originally and observed that it was not in any way connected with the developments that took place subsequently as a result of the necessity of Mr. -

Abstract Council of Islamic Ideology Is a Permanent Constitutional Body

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).27 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).27 Citation: Hussain, S., Gillani, A. H., & Abbas, M. W. (2020). Role of Council of Islamic Ideology in Islamization During Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Era. Global Political Review, V(I), 241-250. doi:10.31703/gpr.2020(V-I).27 Vol. V, No. I (Winter 2020) Pages: 241 – 250 Role of Council of Islamic Ideology in Islamization During Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Era Sajid Hussain* Aftab Hussain Gillani† Muhammad Wasim Abbas‡ p- ISSN: 2521-2982 e- ISSN: 2707-4587 According to the Constitution of Pakistan 1973, the p- ISSN: 2521-2982 Abstract Council of Islamic Ideology is a permanent constitutional body. Its duties are not only to advise the Parliament whether or not the laws are repugnant to Islam in the light of Quran and Sunnah and but Headings also to recommend measures to be promulgated as legislations to promote Islamic way of life in the country. This paper discusses in detail • Abstract the efforts of the Council of Islamic Ideology in Islamization of Pakistan • Key Words in Bhutto’s era. This study is historical research and data has been • Introduction collected through primary and secondary sources. Many important laws • Research Methodology have been enacted, and departments have been established on the • Establishment of the Council of recommendation of the Council of Islamic Ideology. This article will not Islamic Ideology • Recommendations of the Council to only highlight the establishment, importance of the Council of Islamic the Government Ideology but also its achievements during the era of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. -

BORN to BE HANGED Praise Fo R the Book

BORN TO BE HANGED Praise fo r the Book While tracing the making of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto-the most popular leader of his people, Dr Syeda Hameed easily identifies him as a self-destroying character in a Greek tragedy. But the chief merit of this book lies in explaining the factors contributing to his meteoric rise and the unravelling of his mind through a reading of his prison letters with Dr Mubashir Hasan's help, and how Bhutto, with a Janus like posture, tried to build a socialist castle on the fo undation of Islamic ideology. The guardians of vested interest were not duped; they hanged him fo r shaking their throne. An eye-opener fo r students of Pakistan's muddled politics. -I.A. Rehman, Human Rights Activist and Political Analyst, Pakistan Syeda Hameed's labour of love, spanning two decades, has flowered into a vivid portrayal of one of the most intriguing public figures of South Asia -Asif Noorani, Senior Journalist and Author, Pakistan BORN TO BE HANGE POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF ZULFIKAR ALI BHUTTO SYEDA HAMEED RUPA Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/ 16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Sales Centres: Allahabad Bcngaluru Chennai Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu Kolkata Mumbai Copyright «;l Syeda Hameed 2017 Photo courtesy: Author's collection and Sheba George The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author's own and the facts are as reported by her which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers arc not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. -

Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across the Border: the Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Communication Master of Arts Theses College of Communication Winter 3-19-2018 Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry Dina Khdair DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Khdair, Dina, "Globalizing Pakistani Identity Across The Border: The Politics of Crossover Stardom in the Hindi Film Industry" (2018). College of Communication Master of Arts Theses. 31. https://via.library.depaul.edu/cmnt/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Communication at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Communication Master of Arts Theses by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GLOBALIZING PAKISTANI IDENTITY ACROSS THE BORDER: THE POLITICS OF CROSSOVER STARDOM IN THE HINDI FILM INDUSTRY INTRODUCTION In 2010, Pakistani musician and actor Ali Zafar noted how “films and music are one of the greatest tools of bringing in peace and harmony between India and Pakistan. As both countries share a common passion – films and music can bridge the difference between the two.”1 In a more recent interview from May 2016, Zafar reflects on the unprecedented success of his career in India, celebrating his work in cinema as groundbreaking and forecasting a bright future for Indo-Pak collaborations in entertainment and culture.2 His optimism is signaled by a wish to reach an even larger global fan base, as he mentions his dream of working in Hollywood and joining other Indian émigré stars like Priyanka Chopra. -

If I Am Assassinated; Zulfikar Ali Bhutto

IF I AM ASSASSINATED By ZULFIKAR ALI BHUTTO Reproduced in PDF Format By: Sani Hussain Panhwar CONTENTS In The Supreme Court of Pakistan Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 1 1. White Paper or White Lies? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 27 2. Misrepresentation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 33 3.”Warfare,” Rigging and Fraud .. .. .. .. .. .. 46 4. The Election Commission .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 55 5. The Government Machine .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 73 6. The “Larkana-Plan” .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 88 7. Rigged or Fair? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 102 8. The Inner Cancer .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 125 9. The External Crisis .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 138 10. Death Knell .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 154 11. Foreign Hand .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 169 12. The Death Cell and History .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 197 13. The Hour has struck .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 209 Addendum .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 232 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN Criminal Appellate Jurisdiction Criminal Appeal No. 11 of 1978 Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Son of Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto District Jail Rawalpindi ………………………………………. Appellant Versus The State.……………………………………………………….. Respondent The undersigned Appellant respectfully submits: 1. That during the pendency of the present Appeal and while it was being heard before this Honorable Court, the Government of Pakistan has come out with two White Papers, one on the alleged rigging of elections in March 1977, and the other on the alleged misuse of the news media during the tenure of my Government. Obviously the time for publicising the false, fabricated and malicious allegations contained in these two White Papers has been deliberately chosen and is a calculated attempt to prejudice man-kind against me and to prejudice the hearing of my case. The second White Paper on the media, which was issued on 28 August 1978, was in fact printed on 25 March 1978, as would appear from the printing date on the front page and the cover, on which another date was superimposed. -

YAHYA BAKHTIAR Original Letter

Yahya Bakhtiar to Fatima Jinnah [Letter], 2 February 1965 ∗ YAHYA BAKHTIAR M.A., BARRISTER-AT-LAW JINNAH ROAD QUETTA 2nd. Feb. 1965 I am writing this letter to explain my position during the recent meetings of the COP conference and our Working Committee. As soon as the reports of coercion, browbeating and all sorts of illegalities started pouring in at the Flag Staff House and soon thereafter the result of the Presidential election was announced I realized that the same ting will happen during the election to the Assemblies and openly expressed my opinion about boycotting the assembly elections. That night Shoukat Hayat, Pir Saifuddin and Manzar Bashir also arrived in Karachi and I told them about it. They also agreed with me and we came to the conclusion that we should not recognize the Presidential election as legal and proper and demand that election to the Assemblies and the ∗ Mohtarma Fatima Jinnah Papers, F.274, National Archives of Pakistan, Islamabad. Yahya Bakhtiar, M.A., Bar-at-Law was then President, West Pakistan Muslim League (Council) His address as shown in the letter, was Jinnah Road, Quetta. 62 Pakistan Journal of History & Culture, (Fatima Jinnah Number) office of the President be held on the basis of adult franchise and the National Assembly be moved to forthwith amend the Constitution accordingly. Two days later Mr. Fazlur Rahman arrived from Dacca and we discussed the problem with him also and he was already of the same opinion. Then I left for Quetta. It is not a fact that my opinion on the subject was formed by Shaukat or Fazlur Rahman.