Untimely Detritus: Christian Marclay's Cyanotypes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bio Information: CHRISTIAN MARCLAY / TOSHIO KAJIWARA / DJ OLIVE: Djtrio Title: 21 SEPTEMBER 2002 (Cuneiform Rune 348) Format: LP

Bio information: CHRISTIAN MARCLAY / TOSHIO KAJIWARA / DJ OLIVE: djTRIO Title: 21 SEPTEMBER 2002 (Cuneiform Rune 348) Format: LP Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) http://www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: EXPERIMENTAL / SOUND ART / AVANT-GARDE / TURNTABLISM “At various moments, the mix suggested nature sounds, urban cacophony, 12-tone compositions and the tuning of radio dial” – Washington Post “An archeological excavation where whirlpool scratches, microtones and samples of thrift store-mined cheese fly around like poltergeists released from a tomb.” – XLR8R “Some amazing, static-riddled alien music.” – Dusted Start off by dispelling any outmoded notions about taking things at face value – sometimes a DJ is not just a DJ, a record is not a record, and a turntable is more than a record player. These are the basic tenets with which to enter the world of Christian Marclay’s djTRIO, especially in the case of their live recordings. World-renowned multi-media artist Marclay may be best known these days for his globally embraced film collage piece “The Clock,” but he began by redefining the roles of “musician,” “DJ,” and even “artist” itself. Since the late ‘70s, Marclay has created art by masterfully mistreating both vinyl and phonographic equipment, using them both in a manner more consistent with the way an abstract sculptor employs raw materials in the service of a larger vision. Sometimes these sonic journeys utilizing a turntable as a sextant have been in-the-moment experiences and sometimes they’ve been captured for posterity, but 21 September 2002 on Cuneiform Records happens to be both. -

T of À1 Radio

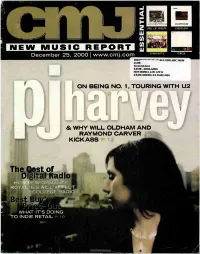

ism JOEL L.R.PHELPS EVERCLEAR ,•• ,."., !, •• P1 NEW MUSIC REPORT M Q AND NOT U CIRCLE December 25, 2000 I www.cmj.com 138.0 ******* **** ** * *ALL FOR ADC 90198 24498 Frederick Gier KUOR -REDLANDS 5319 HONDA AVE APT G ATASCADERO, CA 93422-3428 ON BEING NO. 1, TOURING WITH U2 & WHY WILL OLDHAM AND RAYMOND CARVER KICK ASS tof à1 Radio HOW PERFORMANCE ROYALTIES WILL AFFECT COLLEGE RADIO WHAT IT'S DOING TO INDIE RETAIL INCLUDING THE BLAZING HIT SINGLE "OH NO" ALBUM IN STORES NOW EF •TARIM INEWELII KUM. G RAP at MOP«, DEAD PREZ PHARCIAHE MUNCH •GHOST FACE NOTORIOUS J11" MONEY PASTOR TROY Et MASTER HUM BIG NUMB e PRODIGY•COCOA BROVAZ HATE DOME t.Q-TIIP Et WORDS e!' le.‘111,-ZéRVIAIMPUIMTPIeliElrÓ Issue 696 • Vol 65 • No 2 Campus VVebcasting: thriving. But passion alone isn't enough 11 The Beginning Of The End? when facing the likes of Best Buy and Earlier this month, the U.S. Copyright Office other monster chains, whose predatory ruled that FCC-licensed radio stations tactics are pricing many mom-and-pops offering their programming online are not out of business. exempt from license fees, which could open the door for record companies looking to 12 PJ Harvey: Tales From collect millions of dollars from broadcasters. The Gypsy Heart Colleges may be among the hardest hit. As she prepares to hit the road in support of her sixth and perhaps best album to date, 10 Sticker Shock Polly Jean Harvey chats with CMJ about A passion for music has kept indie music being No. -

Holiday Fund 8 Spectrum 17 Seniors 18 Eating out 25 Shop Talk 26 INSIDE ENJOY CLASS GUIDE

Vol. XXXV, Number 13 N January 3, 2014 PAGE 22 Holiday Fund 8 Spectrum 17 Seniors 18 Eating Out 25 Shop Talk 26 INSIDE ENJOY CLASS GUIDE NUpfront Plane route over Palo Alto eyed Page 5 NHome Website offers remodeling ideas Page 27 NSports Stanford loses 24-20 in the Rose Bowl Page 44 LIGHT UP YOUR LIFE (AND POCKET THE SAVINGS) RECEIVE ENERGY STAR® DISCOUNT LED BULBS! City of Palo Alto Utilities is selling SWITCH Infi nia 60W equivalent LED bulbs for $9.99, and a 40W equivalent for $8.99. (Prices are about half of regular retail!) Take advantage of this great energy-saving offer while supplies last! * t Lifetime residential warranty t 25,000 hour/22 year life t Full 300o light distribution t Warm light (2700K) t Works with most dimmers (See switchlightingco.com/infi nia) tUL rated for indoor, outdoor and damp locations Use the coupon below to receive your discounted energy effi cient LED light bulbs, while supplies last at any of these three locations: Ace Hardware—875 Alma St. Fry’s Electronics—340 Portage Ave. Piazza’s Fine Foods—3922 Middlefi eld Rd. LED DISCOUNT * COUPON ""#$# $ $$' %#$ "# ' %#$# &!" "#' &$ %! $$ !%"# 650-329-2241 www.cityofpaloalto.org/lighting Page 2ÊUÊ>Õ>ÀÞÊÎ]ÊÓä£{ÊUÊ*>ÊÌÊ7iiÞÊUÊÜÜÜ°*>Ì"i°V Sellers Wanted Our Motivated Buyers Need Your Help Buyer 1 Buyer 2 Buyer 3 3 Bed + | 2 Bath + 3 Bed + | 2 Bath + 3 Bed + | 2 Bath + | View 1 Acre lot + Atherton Sharon Heights Woodside | Portola Valley Central Atherton Up to $3,500,000 Emerald Hills Up to $5,000,000 Up to $3,000,000 Buyer 4 Buyer 5 Buyer 6 3 Bed -

Christian Marclay

CHRISTIAN MARCLAY Born 1955, San Rafael, California. Lives and works in London and New York. SELECTED INDIVIDUAL EXHIBITIONS 2016 “Six New Animations”, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, CA 2015 “The Clock,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles “Up and Out”, Cinema Bellevaux, Lausanne, Switzerland “Christian Marclay” Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aurau, Switzerland “Christian Marclay” Artspace, San Antonio, TX “Christian Marclay” White Cube, London, UK “Surround Sounds” Paula Cooper Galley, New York 2013 “Things I’ve Heard,” Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco “The Clock,” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco “The Clock,” Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, OH “The Clock,” Winnipeg Art Gallery, Canada “Christian Marclay,” Paula Cooper Gallery, New York 2012 “The Clock,” Museum of Modern Art, New York “Every Day,” Queen Elizabeth Hall, London “The Clock,” Power Plant, Toronto “The Clock,” Kunsthalle Zurich, Zurich “Seven Windows,” Palais de Tokyo, Paris 2011 “Cyanotypes,” Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco “Scrolls,” Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo “The Clock,” Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; Garage Center for Contemporary Culture, Moscow; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Centre Pompidou, Paris; National Gallery of Canada, Ontario 2010 “The Clock,” White Cube, London “Christian Marclay: Festival,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York “Fourth of July,” Paula Cooper Gallery, New York 2009 “Ephemera,” Louvre Museum, Paris “Performa Biennial,” P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, New York “Video Quartet,” -

President's Report

Massachusetts college of a rt and d esign a nnual r eport J uly 2010–June 2011 Big things are happening here. You can see it in the numbers — undergraduate enrollment up almost 5 percent; the $140 million comprehensive campaign at 89 percent of its goal. You can hear it across campus — the rattle of construction equipment working on the site of the new 21-story residence hall. You can feel it in the air — a palpable energy sparked by local and global community engagement. ¶ The 2010 academic year was anything but ordinary. It was a year when we applauded the achievements of an extraordinary leader, and anticipated the arrival of a new one. And when we celebrated the ingenuity of our faculty, students, and alumni, who continued to expand the boundaries of creativity. ¶ iii Flourish: Alumni Works on Paper The artwork you see throughout these pages appeared in Flourish: i Alumni Works on Paper, hall residence new MassArt’s first juried alumni exhibition held last June in the Bakalar & Paine Galleries. ii The exhibition highlights the wide range of talent and excellence embodied by MassArt’s inners w artists and designers. president, dawn barrett dawn president, th ard aw eadership l lumni lumni our 11 a Leah De Prizio bfa painting ’63 Arbor Vitae, papier-mâché woodblock print, acrylic, 58" x 24" x 15", 2005. Courtesy of the artist. iv Alumni Film Wins Top AWArd v renovATing The gAlleries newspapers, 24" x 24", 2011. Courtesyoftheartist. 2011. x 24", 24" newspapers, ELD Jichova K. Bara _0300 vi , Painting , FAculTy FinAlisTs For icA FosTer prize bfa sim’07 bfa / collage on Czechoslovakian collage onCzechoslovakian vii cAreer conFerence viii neW sTore connecTs ArT WiTh communiTy ix cenTer For design And mediA x ArTWArd Bound lAunch xi FloATing World projecT annual report anddesign collegeofart report massachusetts annual xii solAr decAThlon 1 2 massachusetts college of art and design annual report In September, after 15 years as MassArt’s president, Kay Sloan announced her retirement. -

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17

Art and Vinyl — Artist Covers and Records Komposition René Pulfer Kuratoren: Søren Grammel, Philipp Selzer 17. November 2018 – 03. Februar 2019 Ausstellungsinformation Raumplan Wand 3 Wand 7 Wand 2 Wand 6 Wand 5 Wand 4 Wand 2 Wand 1 ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Komposition René Pulfer Der Basler Künstler René Pulfer, einer der Pioniere der Schweizer Videokunst und Hochschulprofessor an der HGK Basel /FHNW bis 2015, hat sich seit den späten 1970 Jahren auch intensiv mit Sound Art, Kunst im Kontext von Musik (Covers, Booklets, Artist Editions in Mu- sic) interessiert und exemplarische Arbeiten von Künstlerinnen und Künstlern gesammelt. Die Ausstellung konzentriert sich auf Covers und Objekte, bei denen das künstlerische Bild in Form von Zeichnung, Malerei oder Fotografie im Vordergrund steht. Durch die eigenständige Präsenz der Bildwerke treten die üblichen Angaben zur musikalischen und künstlerischen Autorschaft in den Hintergrund. Die Sammlung umfasst historische und aktuelle Beispiele aus einem Zeitraum von über 50 Jahren mit geschichtlich unterschiedlich gewachsenen Kooperationsformen zwischen Kunst und Musik bis zu aktuellen Formen der Multimedialität mit fliessenden Grenzen, so wie bei Rodney Graham mit der offenen Fragestellung: „Am I a musician trapped in an artist's mind or an artist trapped in a musician's body?" ARTIST WORKS for 33 1/3 and 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) Composition René Pulfer The Basel-based artist René Pulfer, one of the pioneers of Swiss video- art and a university professor at the HGK Basel / FHNW until 2015, has been intensively involved with sound art in the context of music since the late 1970s (covers, booklets, artist editions in music ) and coll- ected exemplary works by artists. -

Appropriation Film”

An unauthorized partial recording of Christian Marclay’s The Clock as accessed on Vimeo, May 21, 2015 . Trespassing Hollywood: Property, Space, and the “Appropriation Film” RICHARD MISEk In the two decades since the first exhibition of Douglas Gordon’s 24 Hour Psycho (1993), “appropriation”—a mainstay of visual art since the mid-twentieth century—has become a common feature of experimental filmmaking and artists’ film and video. Many of the most prominent contemporary practitioners in these fields (including Cory Arcangel, Mark Leckey, Christian Marclay, and Nicolas Provost) have made their names by creating montages, collages, mash-ups, and other transformative works from preexisting moving images. Perhaps the clearest evidence so far of appropriation’s prominence within moving-image arts was the 2012 Turner Prize, in which the works of two of the four finalists (Luke Fowler and Elizabeth Price, who won) were videos constructed mainly from archival televi - sion footage. Of course, this artistic turn is symptomatic of a broader cultural turn that has seen media reuse spread to everyday practice. However artists’ audiovisual appropriations may differ from fan-made YouTube supercuts, the two share a cru - cial technological precondition: the ability to copy and transform source files with - out a significant reduction in quality. 1 Applied to video, Nicolas Bourriaud’s char - acterization of contemporary artistic practice as “postproduction” loops back to its original meaning. It describes not only the creative process of “selecting cultural objects and inserting them into new contexts” but also the technologies through which this process takes place: video-editing, sound-mixing, and visual-effects (i.e., “postproduction”) software. -

Sight & Sound Annual Index 2017

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 27 January to December 2017 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 6:52(r) Amour (2012) 5:17; 6:17 Armano Iannucci Shows, The 11:42 Ask the Dust 2:5 Bakewell, Sarah 9:32 Film review titles are also interview with Koreeda Amours de minuit, Les 9:14 Armisen, Fred 8:38 Asmara, Abigail 11:22 Balaban, Bob 5:54 included and are indicated by Hirokazu 7:8-9 Ampolsk, Alan G. 6:40 Armstrong, Jesse 11:41 Asquith, Anthony 2:9; 5:41, Balasz, Béla 8:40 (r) after the reference; age and cinema Amy 11:38 Army 2:24 46; 10:10, 18, 44 Balch, Antony 2:10 (b) after reference indicates Hotel Salvation 9:8-9, 66(r) An Seohyun 7:32 Army of Shadows, The Assange, Julian Balcon, Michael 2:10; 5:42 a book review Age of Innocence, The (1993) 2:18 Anchors Aweigh 1:25 key sequence showing Risk 8:50-1, 56(r) Balfour, Betty use of abstraction 2:34 Anderson, Adisa 6:42 Melville’s iconicism 9:32, 38 Assassin, The (1961) 3:58 survey of her career A Age of Shadows, The 4:72(r) Anderson, Gillian 3:15 Arnold, Andrea 1:42; 6:8; Assassin, The (2015) 1:44 and films 11:21 Abacus Small Enough to Jail 8:60(r) Agony of Love (1966) 11:19 Anderson, Joseph 11:46 7:51; 9:9; 11:11 Assassination (1964) 2:18 Balin, Mireille 4:52 Abandon Normal Devices Agosto (2014) 5:59 Anderson, Judith 3:35 Arnold, David 1:8 Assassination of the Duke Ball, Wes 3:19 Festival 2017, Castleton 9:7 Ahlberg, Marc 11:19 Anderson, Paul Thomas Aronofsky, Darren 4:57 of Guise, The 7:95 Ballad of Narayama, The Abdi, Barkhad 12:24 Ahmed, Riz 1:53 1:11; 2:30; 4:15 mother! 11:5, 14, 76(r) Assassination of Trotsky, The 1:39 (1958) 11:47 Abel, Tom 12:9 Ahwesh, Peggy 12:19 Anderson, Paul W.S. -

Directory of Artists' Fellows & Finalists

NEW YORK FOUNDATION FOR THE ARTS Directory of Artists’ Fellows & Finalists 19 85 Liliana Porter Sorrel Doris Hays Architecture Crafts Film Susan Shatter Lee Hyla Elizabeth Diller Deborah Aguado Alan Berliner Elizabeth Yamin Oliver Lake Laurie Hawkinson John Dodd Bill Brand Meredith Monk David Heymann Lorelei Hamm Ayoka Chenzira Benny Powell John Margolies Wayne Higby Abigail Child Ned Rothenberg Michael Sorkin Patricia Kinsella Kenneth Fink Inter-Arts Pril Smiley Allan Wexler* Graham Marks George Griffin Mary K. Buchen Andrew Thomas Ellen Wexler* Robert Meadow Barbara Kopple William Buchen Judith Moonelis Cinque Lee Dieter Froese Louisa Mueller Christine Noschese Julia Heyward Robert Natalini Rachel Reichman Candace Hill-Montgomery Painting Choreography Douglas Navarra Kathe Sandler James Perry Hoberman Milet Andrejevic John Bernd Betty Woodman Richard Schmiechen Tehching Hsieh Luis Cruz Azaceta Trisha Brown Spike Lee Brenda Hutchinson William Bailey Yoshiko Chuma Patrick Irwin Ross Bleckner Blondell Cummings Barbara Kruger Eugene Brodsky Caren Canier Kathy Duncan Fiction Christian Marclay Karen Andes Martha Diamond Ishmael Houston-Jones Graphics M. Jon Rubin Michael Blaine Humberto Aquino Stephen Ellis Lisa Kraus William Stephens Magda Bogin Barbara Asch Mimi Gross Ralph Lemon Fiona Templeton Ray Federman Nancy Berlin Stewart Hitch Victoria Marks David Humphrey Arthur Flowers Enid Blechman Susan Marshall Yvonne Jacquette Wendy Perron Ralph Lombreglia Rimer Cardillo David Lowe Stephen Petronio Mary Morris Lloyd Goldsmith Music Medrie MacPhee -

Discographie

CHRISTIAN SCHOLZ UNTERSUCHUNGEN ZUR GESCHICHTE UND TYPOLOGIE DER LAUTPOESIE Teil III Discographie GERTRAUD SCHOLZ VERLAG OBERMICHELBACH (C) Copyright Gertraud Scholz Verlag, Obermichelbach 1989 ISBN 3-925599-04-5 (Gesamtwerk) 3-925599-01-0 (Teil I) 3-925599-02-9 (Teil II) 3-925599-03-7 (Teil III) [849] INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 389 [850] 1. ANTHOLOGIEN 389 [850] 2. VORFORMEN 395 [865] 3. AUTOREN 395 [866] II. SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR 439 [972] III. HÖRSPIELE 452 [1010] ANHANG 460 [1028] IV. VOKALKOMPOSITIONEN 460 [1029] V. NACHWORT 471 [1060] [850] I. PRIMÄRLITERATUR 1. ANTHOLOGIEN Absolut CD # 1. New Music Canada. A salute to Canadian composers and performers from coast to coast. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD Absolut CD # 2. The Japanese Perspective. Ed. by David LL Laskin. Special Guest Editor: Toshie Kakinuma. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von Yamatsuka Eye & John Zorn, Ushio Torikai u. a. CD Absolut CD # 3. Improvisation/Composition. Beilage in: Ear Magazine. New York o. J., o. Angabe der Nummer. Beiträge von David Moss, Joan La Barbara u. a. CD The Aerial. A Journal in Sound. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur Foundation 1990, Nr. 1, Winter 1990. AER 1990/1. Mit Beiträgen von David Moss, Malcolm Goldstein, Floating Concrete Octopus, Richard Kostelanetz u. a. CD The Aerial. Santa Fe, NM, USA: Nonsequitur 1990, Nr. 2, Spring 1990. AER 1990/2. Mit Beiträgen von Jin Hi Kim, Annea Lockwood, Hildegard Westerkamp u. a. CD The Aerial. -

CHRISTIAN MARCLAY Parkett 70 – 2004 C Hristian M Arclay CHRISTIAN MARCLAY’S

CHRISTIAN MARCLAY Parkett 70 – 2004 C hristian M arclay CHRISTIAN MARCLAY’S PHILIP SHERBURNE Taking the musical world as his primary material, Christian Marclay fuses the documentary with the imaginary, merging the public and private worlds of listening. Many sound artists have traversed the limits of silence—beyond John Cage, of course, see Francisco López, or Reynols, or Richard Chartier—but Marclay’s work is different. It either emits sound or it does not. His inaudible works may be said, metaphorically, to hum with cultural resonances, but this is ultimately only a metaphor. A great deal of Marclay’s output, possibly the majority of it, is visual or plastic in nature. And yet even this is as much about sound—about the c u l - tural universe of sound—as any recording; perhaps more so, because it concerns the ubiq- uity of sound in culture. Marclay’s work is about the socially inscribed “flip side” of sound; it is about the very fact that I could use the phrase “flip side” as unthinkingly as I just did, real- izing only as I typed it that the term derives from records, and is thus infinitely apropos for use here. Before we consider Christian Marclay in more detail, two recent incidents serve as coinci- dental introductions to his work. Widely reported in the North American media, they hone in on Marclay’s practice as surely as the turntable stylus winds concentrically toward the center of the disc. Several weeks ago, I received an email—a forward of a forward of a forward, in the curi- ously passive manner of Internet activism—alerting me that unscrupulous businessmen were planning an act of wanton destruction, and enlisting my assistance in opposing them. -

Moma EXHIBITION AUTOMATIC UPDATE EXPLORES THE

MoMA’s NINTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL FESTIVAL OF FILM PRESERVATION SHOWCASES NEWLY RESTORED MASTERWORKS AND REDISCOVERIES Festival Features Films by Roger Corman, Forugh Farrokhzad, George Kuchar, Alberto Lattuada, Louis Malle, Agnes Martin, Georges Méliès, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, Jean Rouch, and Seijun Suzuki Guest presenters include Joe Dante, Walter Hill, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Elaine May, Mario Montez, Thelma Schoonmaker, and Martin Scorsese To Save and Project: The Ninth MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation October 14–November 19, 2011 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, September 20, 2011—The Museum of Modern Art presents To Save and Project: The Ninth MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation, the annual festival of preserved and restored films from archives, studios, and distributors around the world, from October 14 through November 19, 2011. This year’s festival comprises over 35 films from 14 countries, virtually all of them having their New York premieres, and some shown in versions never before seen in the United States. Complementing the annual festival is a retrospective devoted to filmmaker Jack Smith, featuring 11 newly struck prints acquired for MoMA’s collection and introduced on November 13 by Mario Montez, star of Smith’s Flaming Creatures (1962–63) and Normal Love (1963–65). To Save and Project is organized by Joshua Siegel, Associate Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art. Opening this year’s festival is Joe Dante’s digital preservation of The Movie Orgy (1968). Dante, who created some of the best genre-bending movies of the past 40 years, including Piranha, The Howling, Gremlins, and Matinee, will introduce a rare screening of The Movie Orgy on October 14.