Arxiv:Physics/9803034V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lausanne 2016: Long Jump W

Women's Long Jump Diamond Race 25.08.2016 Start list Long Jump Time: 21:00 Records Order Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Blessing OKAGBARE-IGHOTEGUONOR NGR 7.12 7.00 6.73 WR 7.52 Galina CHISTYAKOVA URS Leningrad 11.06.88 2 Christabel NETTEY CAN 6.99 6.99 6.75 AR 7.52 Galina CHISTYAKOVA URS Leningrad 11.06.88 NR 6.84 Irene PUSTERLA SUI Chiasso 20.08.11 3 Akela JONES BAR 6.75 6.75 6.75 WJR 7.14 Heike DRECHSLER GDR Bratislava 04.06.83 4 Lorraine UGEN GBR 7.07 6.92 6.76 MR 7.48 Heike DRECHSLER GER 08.07.92 5 Shara PROCTOR GBR 7.07 7.07 6.80 DLR 7.25 Brittney REESE USA Doha 10.05.13 6 Darya KLISHINA RUS 7.52 7.05 6.84 SB 7.31 Brittney REESE USA Eugene 02.07.16 7 Ivana SPANOVIĆ SRB 7.08 7.08 7.08 8 Tianna BARTOLETTA USA 7.49 7.17 7.17 2016 World Outdoor list 7.31 +1.7 Brittney REESE USA Eugene 02.07.16 7.17 +0.6 Tianna BARTOLETTA USA Rio de Janeiro 17.08.16 Medal Winners Diamond Race 7.16 +1.6 Sosthene MOGUENARA GER Weinheim 29.05.16 1 Ivana SPANOVIĆ (SRB) 36 7.08 +0.6 Ivana SPANOVIĆ SRB Rio de Janeiro 17.08.16 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Brittney REESE (USA) 16 7.05 +2.0 Brooke STRATTON AUS Perth 12.03.16 1. Tianna BARTOLETTA (USA) 7.17 3 Christabel NETTEY (CAN) 15 6.95 +0.6 Malaika MIHAMBO GER Rio de Janeiro 17.08.16 2. -

Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & XC Running

//ÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊÀVÃÊvÊÌ iÊ/À>`iÊvÀÊ ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ``iÊ ÃÌ>Vi]ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÃÌ>ViÊ>`ÊÊ ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} ÀÃÃ ÕÌÀÞÊ,Õ} Ê iVÌÊvÊÌ iÊÊ iÃÌÊ,Õ}ÊÀÌViÃÊvÀÊÊ * ÞÃV>Ê `ÕV>ÌÊ }iÃÌÊ>}>âi ÞÊ VÊÃÃ How to Navigate Within this EBook While the different versions of Acrobat Reader do vary slightly, the basic tools are as follows:. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Make Page Print Back to Previous Actual Fit in Fit to Width Larger Page Page View Enlarge Size Page Window of Screen Reduce Drag to the left or right to increase width of pane. TOP OF PAGE Step 1: Click on “Bookmarks” Tab. This pane Click on any title in the Table of will open. Click any article to go directly to that Contents to go to that page. page. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Double click then enter a number to go to that page. Advance 1 Page Go Back 1 Page BOTTOM OF PAGE ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country Tricks of the Trade for Middle Distance, Distance & Cross-Country Running By Dick Moss (All articles are written by the author, except where indicated) Copyright 2004. Published by Physical Education Digest. All rights reserved. ISBN#: 9735528-0-8 Published by Physical Education Digest. Head Office: PO Box 1385, Station B., Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 5K4, Canada Tel/Fax: 705-523-3331 Email: [email protected] www.pedigest.com U.S. Mailing Address Page 3 Box 128, Three Lakes, Wisconsin, 54562, USA ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Tricks of the Trade for MD, Distance & Cross-Country This book is dedicated to Bob Moss, Father, friend and founding partner. -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

PETER TALLBERG an IOC Member Was During My Long Chairmanship of the IOC Athletes’ Moderator • International Olympic Committee Commission

THE SOCIAL AND PROFESSIONAL LIFE When faced with retirement from elite sport, which usually happens in OF ATHLETES DURINg aNd afTER their early thirties, many athletes face a loss of identity, self-confidence, ELITE COMPETITION direction, status and financial security. I have met many interesting business and sports personalities in my life. But by far the finest experience I have had during my 33 years as PETER TALLBERG an IOC member was during my long chairmanship of the IOC Athletes’ Moderator • International Olympic Committee Commission. The members of the Commission were devoted, clever, well informed and motivated. They were mostly young people, who were usually well prepared for meetings, cooperative and well spoken in several languages. I can honestly say that the members of the IOC Athletes’ Commission are the very best group of people I have ever encountered or worked with. I would now like to mention some of the members from the very beginning of the IOC Athletes’ Commission: • Sebastian Coe, today Chairman of the London 2012 Games Organis- ing Committee; • Thomas Bach, today Vice-President of the IOC and President of the German Olympic Sports Confederation; • Kip Keino, today President of the Kenyan Olympic Committee and running an extremely successful children’s home in Kenya. ORIGINAL TEXT IN ENGLISH I could mention many more, but I believe these examples demonstrate that top athletes generally have a significantly higher level of profes- I have been given the task of acting as moderator during this session. This sionally oriented soft skills, such as the ability to focus on goals, time morning, we have listened to four speakers during “The Athletes” plenary management and strong work ethics. -

2020 Olympic Games Statistics

2020 Olympic Games Statistics - Women’s 400m by K Ken Nakamura The records to look for in Tokyo: 1) Can Miller-Uibo become only the second (after Perec) 400m sprinter to win the Olympic twice. Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA 1 Atlanta 1996 2 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS 2 Atla nta 1996 3 3 48.65 Olga Bryzgina URS 1 Seoul 1988 4 4 48.83 Valerie Brisco -Hooks USA 1 Los Angeles 1984 4 48 .83 Marie Jose -Perec 1 Barcelona 1992 6 5 48.88 Marita Koch GDR 1 Moskva 1980 7 6 49.05 Chandra Cheeseborough USA 2 Los Angeles 1984 Slowest winning time since 1976: 49.62 by Christine Ohuruogu (GBR) in 2008 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 1.23 49.28 Irena Szewinska POL Montreal 1976 Min 0.07 49.62 Christine Ohuruogu GBR Beijing 20 08 49.44 Shaunae Miller BAH Rio de Janeiro 2016 Fastest time in each round Round Time Name Nat Venue Year Final 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 Semi-final 49.11 Olga Nazarova URS Seoul 1988 First round 50.11 Sanya Richards USA Athinai 2004 Fastest non-qualifier for the final Time Position Name Nat Venue Year 49.91 5sf1 Jillian Richardson CAN Seoul 1988 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 48.25 Marie -Jose Perec FRA Atlanta 1996 2 48.63 Cathy Freeman AUS Atlanta 1996 3 49.10 Falilat Ogunkoya NGR Atlanta 1996 Last nine Olympics: Year Gold Nat Time Silver Nat Time Bronze Nat Time 2016 Shaunae Miller BAH 49.44 Allyson Felix USA 49.51 Shericka Jackson -

Athletics Records

Best Personal Counseling & Guidance about SSB Contact - R S Rathore @ 9001262627 visit us - www.targetssbinterview.com Athletics Records - 1. 100 Meters Usain Bolt, Jamaica, 9.58. Bolt, who was once a 200-meter specialist, broke the 100-meter world mark for the third time during a thrilling showdown with Tyson Gay at the World Outdoor Championships in Berlin on Aug. 16, 2009. The Jamaican pulled ahead of Gay early in the race and never let up, finishing in 9.58 seconds. The victory came exactly one year after Bolt broke the record for the second time, winning the 2008 Olympic gold medal in 9.69. 2. 200 Meters Usain Bolt, Jamaica, 19.19. Bolt broke his own world mark at the 2009 World Outdoor Track & Field Championships, where he finished in 19.19 seconds on Aug. 20. He first broke Michael Johnson's 12-year-old mark during the Olympic final exactly one year earlier, finishing in 19.30 seconds while running into a slight headwind (0.9 kilometers per hour). 3. 400 Meters Michael Johnson, USA, 43.18. Many expected Johnson to eventually break Butch Reynolds' mark of 43.29 seconds, set in 1988, but 1999 seemed an unlikely year for the record to fall. Johnson suffered from leg injuries that season, missed the U.S. Championships and ran only four 400-meter races before the World Championships (where he gained an automatic entry as the defending champ). By the day of the World final, however, it was apparent that Johnson was in top form and that Reynolds' record was in jeopardy. -

Comparative Analysis on Speed Distribution of Women 400M Finalist Athletes in the World Athletics and Olympic Championships

S. M. Ramadan Theories & Applications, the International Edition Printed Version : (ISSN 2090-5262) Online Version : (ISSN 2090-5270) July 2014, Volume 4, No. 2 Pages (124 - 130) Comparative Analysis on Speed Distribution of Women 400m Finalist Athletes in the World Athletics and Olympic Championships. S. M. Ramadan Department of sports training – the faculty of sports education for women - Alexandria University, Egypt. Abstract The 400m dash sprint is considered to be one of the most interesting and difficult sprint events in the sport of athletics, this is why sports scientists are paying much attention now to develop the means of helping athletes to enhance their performance and numerical achievements through investigating the mechanical and kinematical and other scientific variables of the race trying to obtain reliable results as a base for modern training techniques. This study aims for presenting a comparative analysis on speed distribution of women 400m finalist athletes in the world athletics 2011 and 2012 Olympic championships by means of correlation analysis, regression analysis and cluster analysis, every 50m segment result has been studied as well as total results of world elite women 400m athletes. The main purpose is to reveal the relations between different 50m phases and the final 400m result, and to find out the basic features of their speed distribution, in order to provide scientific references for our women athletes to increase the ability of reaching higher performance levels. Key Words: women, world, 400m, analysis, speed, distribution will have to ask yourself am I going to compete or am I Introduction going to cave?" Michael Johnson, who won the 200 meter he 400 meters, or 400 meter dash, is a common and 400 meter at the 1996 Olympics - and still holds the 400 T sprinting event in track and field competitions. -

Newsletter 2020

NEWSLETTER 2020 POOVAMMA ENJOYING TRANSITION TO SENIOR STATESMAN ROLE IN DYNAMIC RELAY SQUAD M R Poovamma has travelled a long way from being the baby of the Indian athletics contingent in the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing to being the elder FEATURED ATHLETE statesman in the 2018 Asian Games in Jakarta. She has experienced the transition, slipping into the new role MR Poovamma (Photo: 2014 Incheon Asian Games @Getty) effortlessly and enjoying the process, too. “It has been a different experience over the past couple of years. Till 2017, I was part of a squad that had runners who were either as old as me or a couple of years older. But now, most of the girls in the team are six or seven years younger than I am,” she says from Patiala. “On the track they see me as a competitor but outside, they look up to me like a member of their family.” The lockdown, forced by the Covid-19 outbreak, and the aftermath have given her the opportunity to don the leadership mantle. “For a couple of months, I managed the workout of the other girls. I enjoyed the role assigned to me,” says the 30-year-old. “We were able to maintain our fitness even during lockdown.” Poovamma reveals that the women’s relay squad trained in the lawn in the hostel premises. “It was a change off the track. We hung out together. It was not like it was a punishment, being forced to stay away from the track and the gym. Our coaches and Athletics Federation of India President Adille (Sumariwalla) sir and (Dr. -

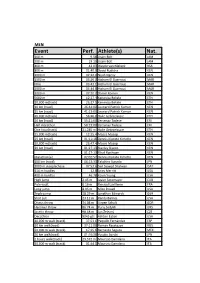

Event Perf. Athlete(S) Nat

MEN Event Perf. Athlete(s) Nat. 100 m 9.58 Usain Bolt JAM 200 m 19.19 Usain Bolt JAM 400 m 43.03 Wayde van Niekerk RSA 800 m 01:40.9 David Rudisha KEN 1000 m 02:12.0 Noah Ngeny KEN 1500 m 03:26.0 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR Mile 03:43.1 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 2000 m 04:44.8 Hicham El Guerrouj MAR 3000 m 07:20.7 Daniel Komen KEN 5000 m 12:37.4 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10,000 m(track) 26:17.5 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 10 km (road) 26:44:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 15 km (road) 41:13:00 Leonard Patrick Komon KEN 20,000 m(track) 56:26.0 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 20 km (road) 55:21:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI Half marathon 58:23:00 Zersenay Tadese ERI One hour(track) 21,285 m Haile Gebrselassie ETH 25,000 m(track) 12:25.4 Moses Mosop KEN 25 km (road) 01:11:18 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 30,000 m(track) 26:47.4 Moses Mosop KEN 30 km (road) 01:27:13 Stanley Biwott KEN 01:27:13 Eliud Kipchoge KEN Marathon[a] 02:02:57 Dennis Kipruto Kimetto KEN 100 km (road) 06:13:33 Takahiro Sunada JPN 3000 m steeplechase 07:53.6 Saif Saaeed Shaheen QAT 110 m hurdles 12.8 Aries Merritt USA 400 m hurdles 46.78 Kevin Young USA High jump 2.45 m Javier Sotomayor CUB Pole vault 6.16 m Renaud Lavillenie FRA Long jump 8.95 m Mike Powell USA Triple jump 18.29 m Jonathan Edwards GBR Shot put 23.12 m Randy Barnes USA Discus throw 74.08 m Jürgen Schult GDR Hammer throw 86.74 m Yuriy Sedykh URS Javelin throw 98.48 m Jan Železný CZE Decathlon 9045 pts Ashton Eaton USA 10,000 m walk (track) 37:53.1 Paquillo Fernández ESP 10 km walk(road) 37:11:00 Roman Rasskazov RUS 20,000 m walk (track) 17:25.6 Bernardo -

RESULTS 1500 Metres Men - Final

Doha (QAT) 27 September - 6 October 2019 RESULTS 1500 Metres Men - Final RECORDS RESULT NAME COUNTRY AGE VENUE DATE World Record WR 3:26.00 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR 24 Roma (Stadio Olimpico) 14 Jul 1998 Championships Record CR 3:27.65 Hicham EL GUERROUJ MAR 25 Sevilla (La Cartuja) 24 Aug 1999 World Leading WL 3:28.77 Timothy CHERUIYOT KEN 24 Lausanne (Pontaise) 5 Jul 2019 Area Record AR National Record NR Personal Best PB Season Best SB 6 October 2019 19:41 START TIME 24° C 64 % TEMPERATURE HUMIDITY PLACE NAME COUNTRY DATE of BIRTH ORDER RESULT 1 Timothy CHERUIYOT KEN 20 Nov 95 2 3:29.26 2 Taoufik MAKHLOUFI ALG 29 Apr 88 4 3:31.38 SB 3 Marcin LEWANDOWSKI POL 13 Jun 87 9 3:31.46 NR 4 Jakob INGEBRIGTSEN NOR 19 Sep 00 6 3:31.70 5 Jake WIGHTMAN GBR 11 Jul 94 12 3:31.87 PB 6 Josh KERR GBR 8 Oct 97 1 3:32.52 PB 7 Ronald KWEMOI KEN 19 Sep 95 7 3:32.72 SB 8 Matthew CENTROWITZ USA 18 Oct 89 3 3:32.81 SB 9 Kalle BERGLUND SWE 11 Mar 96 11 3:33.70 NR 10 Craig ENGELS USA 1 May 94 10 3:34.24 11 Neil GOURLEY GBR 7 Feb 95 5 3:37.30 12 Youssouf HISS BACHIR DJI 1 Jan 87 8 3:37.96 INTERMEDIATE TIMES 100 m13.46 Timothy CHERUIYOT 200 m27.09 Timothy CHERUIYOT 300 m41.06 Timothy CHERUIYOT 400 m55.01 Timothy CHERUIYOT 500 m1:08.91 Timothy CHERUIYOT 600 m1:22.88 Timothy CHERUIYOT 700 m1:40.44 Kalle BERGLUND 800 m1:51.74 Timothy CHERUIYOT 900 m2:06.19 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1000 m2:20.49 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1100 m2:34.54 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1200 m2:48.22 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1300 m3:01.73 Timothy CHERUIYOT 1400 m3:15.37 Timothy CHERUIYOT ALL-TIME TOP LIST SEASON TOP LIST RESULT -

Provided by All-Athletics.Com Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 06.07.2017

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 06.07.2017 Start list 100m Time: 21:20 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Kim COLLINS SKN 9.93 9.93 10.28 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Berlin 16.08.09 2 Henrico BRUINTJIES RSA 9.89 9.97 10.06 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Athina 22.08.04 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 3 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.97 9.97 AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Akani SIMBINE RSA 9.89 9.89 9.92 NR 10.11 Alex WILSON SUI Weinheim 27.05.17 5 Justin GATLIN USA 9.69 9.74 9.95 WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene 13.06.14 6 Ben Youssef MEITÉ CIV 9.96 9.96 9.99 MR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM 23.08.12 7 Alex WILSON SUI 10.11 10.11 10.11 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8 James DASAOLU GBR 9.87 9.91 10.11 SB 9.82 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 2017 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.82 +1.3 Christian COLEMAN USA Eugene 07.06.17 1 Andre DE GRASSE (CAN) 25 9.90 +0.9 Yohan BLAKE JAM Kingston 23.06.17 2016 - Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games 2 Ben Youssef MEITÉ (CIV) 17 9.92 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Pretoria 18.03.17 1. Usain BOLT (JAM) 9.81 3 Chijindu UJAH (GBR) 13 9.93 +1.8 Emmanuel MATADI LBR San Marcos 16.05.17 2. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J.