Indoleamine Hallucinogens in Cluster Headache: Results of the Clusterbusters Medication Use Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Serotonergic System in Migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone

J Headache Pain (2001) 2:S43–S46 © Springer-Verlag 2001 MIGRAINE AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Massimo Leone The serotonergic system in migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone Abstract Serotonin (5-HT) and induce migraine attacks. Moreover serotonin receptors play an impor- different pharmacological preventive tant role in migraine pathophysiolo- therapies (pizotifen, cyproheptadine gy. Changes in platelet 5-HT content and methysergide) are antagonist of are not casually related, but they the same receptor class. On the other may reflect similar changes at a neu- side the activation of 5-HT1B-1D ronal level. Seven different classes receptors (triptans and ergotamines) of serotoninergic receptors are induce a vasocostriction, a block of known, nevertheless only 5-HT2B-2C neurogenic inflammation and pain M. Leone • A. Rigamonti • D. D’Amico and 5HT1B-1D are related to migraine transmission. L. Grazzi • S. Usai • G. Bussone (౧) syndrome. Pharmacological evi- C. Besta National Neurological Institute, Via Celoria 11, I-20133 Milan, Italy dences suggest that migraine is due Key words Serotonin • Migraine • e-mail: [email protected] to an hypersensitivity of 5-HT2B-2C Triptans • m-Chlorophenylpiperazine • Tel.: +39-02-2394264 receptors. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine Pathogenesis Fax: +39-02-70638067 (mCPP), a 5-HT2B-2C agonist, may The 5-HT receptor family is distinguished from all other 5- Introduction 1 HT receptors by the absence of introns in the genes; in addi- tion all are inhibitors of adenylate cyclase [1]. Serotonin (5-HT) and serotonin receptors play an important The 5-HT1A receptor has a high selective affinity for 8- role in migraine pathophysiology. -

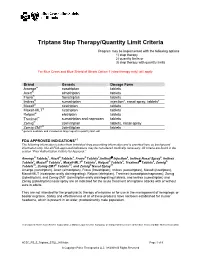

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

(DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact

pharmaceuticals Review Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics of Ayahuasca Alkaloids N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa 1 , Diana Dias-da-Silva 1,2,* , Nelson G. M. Gomes 1,3 , Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira 1,2,4,* and Áurea Madureira-Carvalho 1,3 1 Department of Sciences, IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies, University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS), CESPU, CRL, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.M.B.-d.-C.); ngomes@ff.up.pt (N.G.M.G.); [email protected] (Á.M.-C.) 2 UCIBIO-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Toxicology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 3 LAQV-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 Department of Public Health and Forensic Sciences, and Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.D.-d.-S.); [email protected] (R.J.D.-O.); Tel.: +351-224-157-216 (R.J.D.-O.) Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic botanical beverage originally used by indigenous Amazonian tribes in religious ceremonies and therapeutic practices. While ethnobotanical surveys still indicate its spiritual and medicinal uses, consumption of ayahuasca has been progressively related with a recreational purpose, particularly in Western societies. The ayahuasca aqueous concoction is typically prepared from the leaves of the N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing Psychotria viridis, and the stem and bark of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of harmala alkaloids. -

Daily Triptans for Headache

Expert Opinion Daily Triptans for Headache Case History Submitted by Randolph W. Evans, MD Expert Opinion by Lawrence Robbins, MD Key words: headache, triptans Abbreviations: CDH chronic daily headache (Headache 2001;41:907-909) Will a triptan a day keep the headache away? I advised the patient that the increased frequency of the headaches could be rebound due to sumatriptan CLINICAL HISTORY and that the headaches might decrease by restricting This 47-year-old woman has a history of migraine the sumatriptan to no more than 2 days per week and since aged 4 years. Until 1 year ago, the headaches oc- starting another preventative such as sodium valpro- curred one to two times per week, lasted all day, re- ate. She is concerned about the possible side effects sulted in functional incapacity, and were not relieved of sodium valproate, which she has read can make you by over-the-counter medications or nonsteroidal anti- fat and bald. She also stated that the headaches were inflammatory drugs. About 10 years ago, she was tak- quite tolerable with the daily sumatriptan and she ing Fiorinal #3 but stopped when she developed could not see the difference between taking daily rebound headaches. She has been on multiple preven- sumatriptan as compared to a preventative which may tative medications including amitriptyline, -blockers, or may not work and may have significant side effects. paroxetine, fluoxetine, and verapamil which were ei- Questions.—Is there evidence to support daily ther not effective or stopped due to side effects. triptan use for migraine? What would you recom- One year ago, she saw another neurologist and mend in this case? had an MRI scan of the brain with normal findings. -

The Impact of Triptan and Doxycycline on Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in Acute Migraine: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial Study Protocol

iMedPub Journals INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MEDICINE 2015 http://journals.imed.pub SECTION: NEUROLOGY Vol. 8 No. 13 ISSN: 1755-7682 doi: 10.3823/1612 The impact of triptan and doxycycline on neuroinflammatory biomarkers in acute migraine: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial STUDY PROTOCOL Shaheen E Lakhan, MD, Abstract PhD, MEd, MS1 Background: Increased inflammatory cytokines and matrix meta- 1 Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, lloproteinases (MMPs) have been recently implicated in migraine. In- Euclid Ave, S100C, Cleveland OH . flammation may be a key player in the pathophysiology of migraine by altering blood-brain barrier (BBB) function. As an inflammation induced MMP, MMP-9 is involved in both BBB disruption and neuro- Contact information: pathic pain, and is largely derived by neutrophil degranulation during neutrophil-BBB interaction. The tetracycline group of antibiotics may Shaheen E Lakhan, MD, PhD, MEd, MS. Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, suppress MMP production and neutrophil degranulation. 9500 Euclid Ave, S100C, Cleveland OH 44195. Methods/Design: We hypothesize that migraine is a primary neu- Tel: (216) 444-2200 roinflammatory disorder. We will address this theory by measuring serum biomarkers in healthy controls and after one of three abortive slakhan @gnif.org therapy strategies for acute migraine attacks and inter-ictally. We intend to investigate known neuroinflammatory biomarkers with a focus on BBB breakdown during acute migraine attacks and assess marker responses to conventional treatment (triptans), novel MMP targeted therapy (doxycycline), or a combination of triptan and do- xycycline. We will measure the effects of the interventions on neu- roinflammatory markers for acute migraine attacks, clinical outcomes (headache relief and recurrence) for acute migraine attacks, inter- ictal neuroinflammatory load per serum biomarkers in migraineurs versus healthy controls, and neuroinflammatory markers correlation with headache duration and peak headache intensity during acute migraine attacks. -

United States Patent 19 11) Patent Number: 5,387,604 Mcdonald Et Al

US005387604A United States Patent 19 11) Patent Number: 5,387,604 McDonald et al. 45 Date of Patent: Feb. 7, 1995 (54) 14 BENZODIOXIN DERIVATIVES AND pp. 323-330, Role of 5HT1-like receptors in the reduc THEIR USE AS SEROTONIN 5HT tion of porcine cranial arteriovenous anastomotic shunt AGONSTS ing by Sumatriptan. 75 Inventors: Ian A. McDonald, Loveland; Ronald Saxena, et al, TiPS, May 1989, vol. 10, pp. 200-204; C. Bernotas, Cincinnati; Mark W. 5HT1-like receptor agonists and the pathophysiology Dudley, Somerville; Jeffrey S. of migraine. Sprouse, Cincinnati, all of Ohio Hamel et al., Br. J. Pharmacol, (1991), 102, pp. 227-233; Contractile 5HT1 receptors in human isolated pial arte 73) Assignee: Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., rioles: correlation with 5-HT1D binding sites. Cincinnati, Ohio Edward E. Schwiezer, et al.; Psychopharmacology Bul 21 Appl. No.: 962,434 leting, vol. 22, No. 1, 1986, pp. 183-185; Open Trial of Buspirone in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disor 22 Filed: Oct. 16, 1992 der. Related U.S. Application Data European Journal of Pharmacology, 180 (1990) pp. 339-349, Dreteler, et al.; Comparison of the cardiovas 60 Division of Ser. No. 735,700, Jul. 30, 1991, Pat. No. cular effects of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist flexinoxan 5,189,179, which is a continuation-in-part of Ser. No. with that of 8-OH-DPAT in the rat. 574,710, Aug. 29, 1990, abandoned. European Journal of Pharmacology, 182 (1990) 63-72, 51) int. C.6 .................. C07D 319/20: A61K 31/335. Connor, et al.; Cardiovascular effects of 5HT1 receptor 52 U.S. -

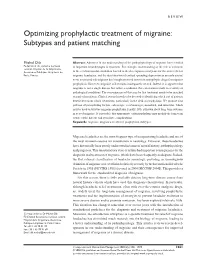

Optimizing Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine: Subtypes and Patient Matching

REVIEW Optimizing prophylactic treatment of migraine: Subtypes and patient matching Michel Dib Abstract: Advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of migraine have resulted Fédération du système nerveux in important breakthroughs in treatment. For example, understanding of the role of serotonin central, Hôpital de la Salpêtrière, Assistance Publique- Hôpitaux de in the cerebrovascular circulation has led to the development of triptans for the acute relief of Paris, France migraine headaches, and the identifi cation of cortical spreading depression as an early central event associated wih migraine has brought renewed interest in antiepileptic drugs for migraine prophylaxis. However, migraine still remains inadequately treated. Indeed, it is apparent that migraine is not a single disease but rather a syndrome that can manifest itself in a variety of pathological conditions. The consequences of this may be that treatment needs to be matched to particular patients. Clinical research needs to be devoted to identifying which sort of patients benefi t best from which treatments, particularly in the fi eld of prophylaxis. We propose four patterns of precipitating factors (adrenergic, serotoninergic, menstrual, and muscular) which may be used to structure migraine prophylaxis. Finally, little is known about long-term outcome in treated migraine. It is possible that appropriate early prophylaxis may modify the long-term course of the disease and avoid late complications. Keywords: migraine, diagnosis, treatment, prophylaxis, subtypes Migraine headaches are the most frequent type of incapacitating headache and one of the most common reasons for consultation in neurology. However, these headaches have historically been poorly understood in terms of natural history, pathophysiology and prognosis. -

L-Tryptophan

2008 368/L-THEANINE PDR FOR NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS Sugiyama T, Sadzuka' Y. Enhancing effects of green tea death. Pellagra is a vitamin B3 deficiency disease caused by components on the antitumor activity of adriamycin against dietary lack of niacin and protein, especially proteins M5076 ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Lef(. 1998; 133: 19-26 ... containing the essential amino acid L-tryptophan., Because Sugiyama T, Sadzuka Y. Theanine, a specific glutamate L-tryptophan can be converted into niacin, foods with L derivative in green tea, reduces the adverse reactions of tryptophan but without niacin, such as 'milk, prevent pellagra. doxorubicin by changing the glutathione level. Cancer Lett .. However, if dietary L-tryptophan is diverted into the 2004;212(2): 177 -184. production of protein, niacin deficiency may still exist, Sugiyama T, Sadzuka Y, Sonobe T: Theanine, a major amino leading to pell_agra. acid in green tea,' inhibits leukopenia and enhances antitumor activity induce by idarubicin. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. By the end of the 1980s, some millions of people, mainly 1999;40: \O(Abstract 63). ' women 'and mainly in the United States, were using Yamada T, Terashima T, Honma H, et al. Effects of theanine, supplemental, L-tryptophan for a variety of reasons-pre a unique amino acid in tea leaves, on memory in a rat menstrual sY!1drome (PMS), sleep disorders, anxiety, depres behavioral test.. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72(~): I ~56- sion, fibromyalgia, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and 1359. ' chronic pain syndromes. Supplemental L-tryptophan was Yamada T, Terashima T, Kawano S, et al. Theanine, gamma also used ,as an adjunct in the treatment of cocaine, glutamylethyl~mide, a unique amino acid in tea leav~s, amphetamirie, alcohol and other drug abuse and for jet lag. -

Nitric Oxide

P1: KWW/KKL P2: KWW/HCN QC: KWW/FLX T1: KWW GRBT050-15 Olesen- 2057G GRBT050-Olesen-v6.cls August 18, 2005 15:30 ••Chapter 15 ◗ Nitric Oxide Andrew A. Parsons The importance of nitric oxide (NO) in modulation of type tool inhibitor compounds that were simple analogs of biological pathways has been known for over 20 years. The arginine led to the use of these compounds to probe into seminal studies by Furchgott and Zwadzki that provided the biological role of NO in physiology and pathophys- an initial identification of a labile relaxing factor released iology. Many effects of NO were subsequently suggested from endothelial cells was a stimulus for many investiga- and involved many organ systems and integrated biologi- tors to identify the nature of the transmitter and explore its cal pathways. NO is now believed to play a key role in many role in biology (13). The tremendous volume of research physiologic processes such as in the gastrointestinal tract, papers on NO over the last two decades is a testament to respiratory and cardiovascular systems, as well as the CNS. the key physiologic and pathophysiologic roles that have The first new medicines to modulate the NO pathway have been attributed to this molecule. also been developed for male erectile dysfunction. The wealth of knowledge surrounding this molecule is represented by a variety of excellent reviews that provide a detailed account of the molecular and cellular effects of CONTROL AND REGULATION OF this agent (see Forstermann et al. [12], Ignarro [22]). The NITRIC OXIDE PRODUCTION aim of this manuscript is to provide a brief overview of how NO is generated by enzyme systems and how it can A schematic representation of the steps involved in the en- produce its biological actions with respect to its potential zymatic production of NO is shown in Figure 15-1. -

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine

Triptan Therapy for Acute Migraine Headache John Farr Rothrock, MD University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL Deborah I. Friedman, MD, MPH University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX The “triptans” are 5HT-1B/1D receptor agonists that were developed to treat acute migraine and acute cluster headache. Sumatriptan, the original triptan preparation, has been in general use since 1993, so there has been considerable experience with triptans over time. There are currently seven oral triptans on the market in the United States: sumatriptan (Imitrex™), naratriptan (Amerge™), zolmitriptan (Zomig™), rizatriptan (Maxalt™), almotriptan (Axert™), frovatriptan (Frova™), and eletriptan (Relpax™); brand names may differ by country. There is also a combination preparation of oral sumatriptan/naproxen (Treximet™). Two triptans (sumatriptan, zolmitriptan) are marketed as nasal sprays, and sumatriptan is available for subcutaneous injection, including a needle-free subcutaneous delivery system (Sumavel™). Sumatriptan suppositories are marketed in Europe but not in North America. Zolmitriptan and rizatriptan are sold in an oral disintegrating tablet or “melt” formulation as well as in tablet form; while the “melt” formulations may be more convenient (no liquid is required to propel them into the stomach), they are absorbed similarly to regular tablets and there is no evidence to suggest that they work faster than the tablet formulations. Some patients with migraine-associated nausea prefer the disintegrating tablets while others cannot tolerate their taste. Although all of the triptans initially were investigated for the treatment of migraine headache of moderate to severe intensity and were superior to placebo in those pivotal trials, they appear to be more consistently effective when used to treat migraine earlier in the attack, when the headache is still mild to moderate. -

Triptans in the Treatment of Migraine in Adults

The role of triptans in the treatment of migraine in adults 28 Paracetamol or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) can be used first-line for pain relief in acute migraine. A triptan can then be trialled if this was not successful. Combination treatment with a triptan and paracetamol or NSAID may be required for some patients. Most triptans are similarly effective, so choice is usually based on formulation, e.g. a non-oral preparation may be more suitable for patients with nausea or vomiting. To avoid medication overuse headache, triptan use should not exceed ten or more days per month. Migraine is a condition characterised by attacks of moderate A stepwise approach to managing migraine: to severe, throbbing headache, which is usually unilateral. This triptans are appropriate at step two is often associated with other symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, photophobia or phonophobia. Approximately one- There are a number of treatment guidelines for acute migraine, third of patients with migraines also experience a preceding all of which differ slightly in their recommended approach (see aura. Worldwide, approximately one in every seven people the NICE and BASH guidelines).3, 4 Most algorithms, however, are affected by migraines, which are often associated with recommend stepwise treatment, with triptans usually tried significant personal and socioeconomic impact.1 In the Global after paracetamol and NSAIDs. Burden of Disease Survey 2010, migraine was ranked as the third most prevalent disorder and the seventh-highest specific A reasonable approach is: 2 cause of disability. Step 1: Over-the-counter analgesics (paracetamol, NSAIDs) Step 2: Triptan For information on diagnosing migraine, see: Step 3: Combination treatment with a triptan and an NSAID National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) +/- anti-emetic (prochlorperazine, metoclopramide) at Guideline: Headaches. -

Cyclisation of Indoles by Using Orthophosphoric Acid in Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan

Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 2013, 5(8):107-109 ISSN : 0975-7384 Research Article CODEN(USA) : JCPRC5 Cyclisation of indoles by using orthophosphoric acid in sumatriptan and rizatriptan K. Sudarshan Rao, K. Nageswara Rao, Bhausaheb Chavan, P. Muralikrishna and A. Jayashree Centre for Chemical Sciences and Technology, IST, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Kukatpally, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT A simple and Novel improved process for the preparation of pure Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan, the cyclisation of indole ring by the using of ortho phosphoric acid. The present work describes the detection, origin, synthesis, characterization and providing a commercial method to synthesize Sumatriptan and Rizatriptan. The procedure developed has several advantages such as mild reaction conditions, convenient operations and easily obtained materials. The synthetic method is suitable for industrial manufacture. Keywords: Cyclisation, Sumatriptan, Rizatriptan, ortho phosphoric acid, _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Triptans are a family of tryptamine-based drugs used as abortive medication in the treatment of migraines and cluster headaches. They were first introduced in the 1990s. While effective at treating individual headaches, they do not provide preventative treatment and are not considered a cure. The first triptan (i.e., tryptamine derivative) to be marketed for the acute treatment of migraine, sumatriptan, has been so successful that a number of second generation triptans are now marketed or in the late stages of clinical development 1,2 . The triptans represent a breakthrough in acute migraine treatment, being far more selective for 5-HT1B-1D receptors than their relatively nonselective predecessor’s ergotamine and dihydroergotamine (DHE) 3,4 .