Optimizing Prophylactic Treatment of Migraine: Subtypes and Patient Matching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ERJ-01090-2018.Supplement

Shaheen et al Online data supplement Prescribed analgesics in pregnancy and risk of childhood asthma Seif O Shaheen, Cecilia Lundholm, Bronwyn K Brew, Catarina Almqvist. 1 Shaheen et al Figure E1: Data available for analysis Footnote: Numbers refer to adjusted analyses (complete data on covariates) 2 Shaheen et al Table E1. Three classes of analgesics included in the analyses ATC codes Generic drug name Opioids N02AA59 Codeine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AA79 Codeine, combinations with psycholeptics N02AA08 Dihydrocodeine N02AA58 Dihydrocodeine, combinations N02AC04 Dextropropoxyphene N02AC54 Dextropropoxyphene, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02AX02 Tramadol Anti-migraine N02CA01 Dihydroergotamine N02CA02 Ergotamine N02CA04 Methysergide N02CA07 Lisuride N02CA51 Dihydroergotamine, combinations N02CA52 Ergotamine, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02CA72 Ergotamine, combinations with psycholeptics N02CC01 Sumatriptan N02CC02 Naratriptan N02CC03 Zolmitriptan N02CC04 Rizatriptan N02CC05 Almotriptan N02CC06 Eletriptan N02CC07 Frovatriptan N02CX01 Pizotifen N02CX02 Clonidine N02CX03 Iprazochrome N02CX05 Dimetotiazine N02CX06 Oxetorone N02CB01 Flumedroxone Paracetamol N02BE01 Paracetamol N02BE51 Paracetamol, combinations excluding psycholeptics N02BE71 Paracetamol, combinations with psycholeptics 3 Shaheen et al Table E2. Frequency of analgesic classes prescribed to the mother during pregnancy Opioids Anti- Paracetamol N % migraine No No No 459,690 93.2 No No Yes 9,091 1.8 Yes No No 15,405 3.1 No Yes No 2,343 0.5 Yes No -

The Serotonergic System in Migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone

J Headache Pain (2001) 2:S43–S46 © Springer-Verlag 2001 MIGRAINE AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY Massimo Leone The serotonergic system in migraine Andrea Rigamonti Domenico D’Amico Licia Grazzi Susanna Usai Gennaro Bussone Abstract Serotonin (5-HT) and induce migraine attacks. Moreover serotonin receptors play an impor- different pharmacological preventive tant role in migraine pathophysiolo- therapies (pizotifen, cyproheptadine gy. Changes in platelet 5-HT content and methysergide) are antagonist of are not casually related, but they the same receptor class. On the other may reflect similar changes at a neu- side the activation of 5-HT1B-1D ronal level. Seven different classes receptors (triptans and ergotamines) of serotoninergic receptors are induce a vasocostriction, a block of known, nevertheless only 5-HT2B-2C neurogenic inflammation and pain M. Leone • A. Rigamonti • D. D’Amico and 5HT1B-1D are related to migraine transmission. L. Grazzi • S. Usai • G. Bussone (౧) syndrome. Pharmacological evi- C. Besta National Neurological Institute, Via Celoria 11, I-20133 Milan, Italy dences suggest that migraine is due Key words Serotonin • Migraine • e-mail: [email protected] to an hypersensitivity of 5-HT2B-2C Triptans • m-Chlorophenylpiperazine • Tel.: +39-02-2394264 receptors. m-Chlorophenylpiperazine Pathogenesis Fax: +39-02-70638067 (mCPP), a 5-HT2B-2C agonist, may The 5-HT receptor family is distinguished from all other 5- Introduction 1 HT receptors by the absence of introns in the genes; in addi- tion all are inhibitors of adenylate cyclase [1]. Serotonin (5-HT) and serotonin receptors play an important The 5-HT1A receptor has a high selective affinity for 8- role in migraine pathophysiology. -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

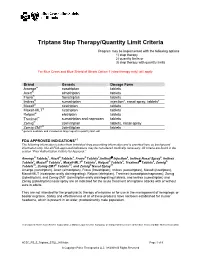

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria

Triptans Step Therapy/Quantity Limit Criteria Program may be implemented with the following options 1) step therapy 2) quantity limits or 3) step therapy with quantity limits For Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois Option 1 (step therapy only) will apply. Brand Generic Dosage Form Amerge® naratriptan tablets Axert® almotriptan tablets Frova® frovatriptan tablets Imitrex® sumatriptan injection*, nasal spray, tablets* Maxalt® rizatriptan tablets Maxalt-MLT® rizatriptan tablets Relpax® eletriptan tablets Treximet™ sumatriptan and naproxen tablets Zomig® zolmitriptan tablets, nasal spray Zomig-ZMT® zolmitriptan tablets * generic available and included as target agent in quantity limit edit FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS1-7 The following information is taken from individual drug prescribing information and is provided here as background information only. Not all FDA-approved indications may be considered medically necessary. All criteria are found in the section “Prior Authorization Criteria for Approval.” Amerge® Tablets1, Axert® Tablets2, Frova® Tablets3,Imitrex® injection4, Imitrex Nasal Spray5, Imitrex Tablets6, Maxalt® Tablets7, Maxalt-MLT® Tablets7, Relpax® Tablets8, Treximet™ Tablets9, Zomig® Tablets10, Zomig-ZMT® Tablets10, and Zomig® Nasal Spray11 Amerge (naratriptan), Axert (almotriptan), Frova (frovatriptan), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Maxalt (rizatriptan), Maxalt-MLT (rizatriptan orally disintegrating), Relpax (eletriptan), Treximet (sumatriptan/naproxen), Zomig (zolmitriptan), and Zomig-ZMT (zolmitriptan orally disintegrating) tablets, and Imitrex (sumatriptan) and Zomig (zolmitriptan) nasal spray are all indicated for the acute treatment of migraine attacks with or without aura in adults. They are not intended for the prophylactic therapy of migraine or for use in the management of hemiplegic or basilar migraine. Safety and effectiveness of all of these products have not been established for cluster headache, which is present in an older, predominantly male population. -

(DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact

pharmaceuticals Review Toxicokinetics and Toxicodynamics of Ayahuasca Alkaloids N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), Harmine, Harmaline and Tetrahydroharmine: Clinical and Forensic Impact Andreia Machado Brito-da-Costa 1 , Diana Dias-da-Silva 1,2,* , Nelson G. M. Gomes 1,3 , Ricardo Jorge Dinis-Oliveira 1,2,4,* and Áurea Madureira-Carvalho 1,3 1 Department of Sciences, IINFACTS-Institute of Research and Advanced Training in Health Sciences and Technologies, University Institute of Health Sciences (IUCS), CESPU, CRL, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal; [email protected] (A.M.B.-d.-C.); ngomes@ff.up.pt (N.G.M.G.); [email protected] (Á.M.-C.) 2 UCIBIO-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Toxicology, Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 3 LAQV-REQUIMTE, Laboratory of Pharmacognosy, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Porto, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal 4 Department of Public Health and Forensic Sciences, and Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, 4200-319 Porto, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.D.-d.-S.); [email protected] (R.J.D.-O.); Tel.: +351-224-157-216 (R.J.D.-O.) Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 23 October 2020 Abstract: Ayahuasca is a hallucinogenic botanical beverage originally used by indigenous Amazonian tribes in religious ceremonies and therapeutic practices. While ethnobotanical surveys still indicate its spiritual and medicinal uses, consumption of ayahuasca has been progressively related with a recreational purpose, particularly in Western societies. The ayahuasca aqueous concoction is typically prepared from the leaves of the N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing Psychotria viridis, and the stem and bark of Banisteriopsis caapi, the plant source of harmala alkaloids. -

Daily Triptans for Headache

Expert Opinion Daily Triptans for Headache Case History Submitted by Randolph W. Evans, MD Expert Opinion by Lawrence Robbins, MD Key words: headache, triptans Abbreviations: CDH chronic daily headache (Headache 2001;41:907-909) Will a triptan a day keep the headache away? I advised the patient that the increased frequency of the headaches could be rebound due to sumatriptan CLINICAL HISTORY and that the headaches might decrease by restricting This 47-year-old woman has a history of migraine the sumatriptan to no more than 2 days per week and since aged 4 years. Until 1 year ago, the headaches oc- starting another preventative such as sodium valpro- curred one to two times per week, lasted all day, re- ate. She is concerned about the possible side effects sulted in functional incapacity, and were not relieved of sodium valproate, which she has read can make you by over-the-counter medications or nonsteroidal anti- fat and bald. She also stated that the headaches were inflammatory drugs. About 10 years ago, she was tak- quite tolerable with the daily sumatriptan and she ing Fiorinal #3 but stopped when she developed could not see the difference between taking daily rebound headaches. She has been on multiple preven- sumatriptan as compared to a preventative which may tative medications including amitriptyline, -blockers, or may not work and may have significant side effects. paroxetine, fluoxetine, and verapamil which were ei- Questions.—Is there evidence to support daily ther not effective or stopped due to side effects. triptan use for migraine? What would you recom- One year ago, she saw another neurologist and mend in this case? had an MRI scan of the brain with normal findings. -

The Impact of Triptan and Doxycycline on Neuroinflammatory Biomarkers in Acute Migraine: Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial Study Protocol

iMedPub Journals INTERNATIONAL ARCHIVES OF MEDICINE 2015 http://journals.imed.pub SECTION: NEUROLOGY Vol. 8 No. 13 ISSN: 1755-7682 doi: 10.3823/1612 The impact of triptan and doxycycline on neuroinflammatory biomarkers in acute migraine: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial STUDY PROTOCOL Shaheen E Lakhan, MD, Abstract PhD, MEd, MS1 Background: Increased inflammatory cytokines and matrix meta- 1 Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, lloproteinases (MMPs) have been recently implicated in migraine. In- Euclid Ave, S100C, Cleveland OH . flammation may be a key player in the pathophysiology of migraine by altering blood-brain barrier (BBB) function. As an inflammation induced MMP, MMP-9 is involved in both BBB disruption and neuro- Contact information: pathic pain, and is largely derived by neutrophil degranulation during neutrophil-BBB interaction. The tetracycline group of antibiotics may Shaheen E Lakhan, MD, PhD, MEd, MS. Neurological Institute, Cleveland Clinic, suppress MMP production and neutrophil degranulation. 9500 Euclid Ave, S100C, Cleveland OH 44195. Methods/Design: We hypothesize that migraine is a primary neu- Tel: (216) 444-2200 roinflammatory disorder. We will address this theory by measuring serum biomarkers in healthy controls and after one of three abortive slakhan @gnif.org therapy strategies for acute migraine attacks and inter-ictally. We intend to investigate known neuroinflammatory biomarkers with a focus on BBB breakdown during acute migraine attacks and assess marker responses to conventional treatment (triptans), novel MMP targeted therapy (doxycycline), or a combination of triptan and do- xycycline. We will measure the effects of the interventions on neu- roinflammatory markers for acute migraine attacks, clinical outcomes (headache relief and recurrence) for acute migraine attacks, inter- ictal neuroinflammatory load per serum biomarkers in migraineurs versus healthy controls, and neuroinflammatory markers correlation with headache duration and peak headache intensity during acute migraine attacks. -

Sample Chapter from Martindale

670 Antimigraine Drugs Antimigraine Drugs periods. Other drugs under investigation include gabapen- 4. Anonymous. Management of medication overuse headache. Drug Ther Bull Cluster headache, p. 670 tin, melatonin, and topiramate.4,9-11,13 2010; 48: 2–6. 5. Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and Medication-overuse headache, p. 670 Paroxysmal hemicrania is a rare variant of cluster migraine progression. Neurology 2008; 71: 1821–8. Migraine, p. 670 headache and differs mainly in the high frequency and 6. British Association for the Study of Headache. Guidelines for all Post-dural puncture headache, p. 671 shorter duration of individual attacks. One of its features, healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, which may be diagnostic, is its invariable response to tension-type, cluster and medication-overuse headache. 3rd edn. Tension-type headache, p. 671 (issued 18th January, 2007; 1st revision, September 2010). Available at: 10 indometacin. http://217.174.249.183/upload/NS_BASH/2010_BASH_Guidelines.pdf 1. Dodick DW, Capobianco DJ. Treatment and management of cluster (accessed 01/12/10) headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2001; 5: 83–91. 7. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management This chapter reviews the management of headache, in 2. Zakrzewska JM. Cluster headache: review of literature. Br J Oral of headache in adults (issued November 2008). Available at: http:// particular migraine and cluster headache, and the drugs Maxillofac Surg 2001; 39: 103–13. www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign107.pdf (accessed 26/01/09) Drug Safety used mainly for their treatment. The mechanisms of head 3. Ekbom K, Hardebo JE. -

United States Patent 19 11) Patent Number: 5,387,604 Mcdonald Et Al

US005387604A United States Patent 19 11) Patent Number: 5,387,604 McDonald et al. 45 Date of Patent: Feb. 7, 1995 (54) 14 BENZODIOXIN DERIVATIVES AND pp. 323-330, Role of 5HT1-like receptors in the reduc THEIR USE AS SEROTONIN 5HT tion of porcine cranial arteriovenous anastomotic shunt AGONSTS ing by Sumatriptan. 75 Inventors: Ian A. McDonald, Loveland; Ronald Saxena, et al, TiPS, May 1989, vol. 10, pp. 200-204; C. Bernotas, Cincinnati; Mark W. 5HT1-like receptor agonists and the pathophysiology Dudley, Somerville; Jeffrey S. of migraine. Sprouse, Cincinnati, all of Ohio Hamel et al., Br. J. Pharmacol, (1991), 102, pp. 227-233; Contractile 5HT1 receptors in human isolated pial arte 73) Assignee: Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals Inc., rioles: correlation with 5-HT1D binding sites. Cincinnati, Ohio Edward E. Schwiezer, et al.; Psychopharmacology Bul 21 Appl. No.: 962,434 leting, vol. 22, No. 1, 1986, pp. 183-185; Open Trial of Buspirone in the Treatment of Major Depressive Disor 22 Filed: Oct. 16, 1992 der. Related U.S. Application Data European Journal of Pharmacology, 180 (1990) pp. 339-349, Dreteler, et al.; Comparison of the cardiovas 60 Division of Ser. No. 735,700, Jul. 30, 1991, Pat. No. cular effects of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist flexinoxan 5,189,179, which is a continuation-in-part of Ser. No. with that of 8-OH-DPAT in the rat. 574,710, Aug. 29, 1990, abandoned. European Journal of Pharmacology, 182 (1990) 63-72, 51) int. C.6 .................. C07D 319/20: A61K 31/335. Connor, et al.; Cardiovascular effects of 5HT1 receptor 52 U.S. -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

L-Tryptophan

2008 368/L-THEANINE PDR FOR NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS Sugiyama T, Sadzuka' Y. Enhancing effects of green tea death. Pellagra is a vitamin B3 deficiency disease caused by components on the antitumor activity of adriamycin against dietary lack of niacin and protein, especially proteins M5076 ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Lef(. 1998; 133: 19-26 ... containing the essential amino acid L-tryptophan., Because Sugiyama T, Sadzuka Y. Theanine, a specific glutamate L-tryptophan can be converted into niacin, foods with L derivative in green tea, reduces the adverse reactions of tryptophan but without niacin, such as 'milk, prevent pellagra. doxorubicin by changing the glutathione level. Cancer Lett .. However, if dietary L-tryptophan is diverted into the 2004;212(2): 177 -184. production of protein, niacin deficiency may still exist, Sugiyama T, Sadzuka Y, Sonobe T: Theanine, a major amino leading to pell_agra. acid in green tea,' inhibits leukopenia and enhances antitumor activity induce by idarubicin. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. By the end of the 1980s, some millions of people, mainly 1999;40: \O(Abstract 63). ' women 'and mainly in the United States, were using Yamada T, Terashima T, Honma H, et al. Effects of theanine, supplemental, L-tryptophan for a variety of reasons-pre a unique amino acid in tea leaves, on memory in a rat menstrual sY!1drome (PMS), sleep disorders, anxiety, depres behavioral test.. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2008;72(~): I ~56- sion, fibromyalgia, seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and 1359. ' chronic pain syndromes. Supplemental L-tryptophan was Yamada T, Terashima T, Kawano S, et al. Theanine, gamma also used ,as an adjunct in the treatment of cocaine, glutamylethyl~mide, a unique amino acid in tea leav~s, amphetamirie, alcohol and other drug abuse and for jet lag. -

Nitric Oxide

P1: KWW/KKL P2: KWW/HCN QC: KWW/FLX T1: KWW GRBT050-15 Olesen- 2057G GRBT050-Olesen-v6.cls August 18, 2005 15:30 ••Chapter 15 ◗ Nitric Oxide Andrew A. Parsons The importance of nitric oxide (NO) in modulation of type tool inhibitor compounds that were simple analogs of biological pathways has been known for over 20 years. The arginine led to the use of these compounds to probe into seminal studies by Furchgott and Zwadzki that provided the biological role of NO in physiology and pathophys- an initial identification of a labile relaxing factor released iology. Many effects of NO were subsequently suggested from endothelial cells was a stimulus for many investiga- and involved many organ systems and integrated biologi- tors to identify the nature of the transmitter and explore its cal pathways. NO is now believed to play a key role in many role in biology (13). The tremendous volume of research physiologic processes such as in the gastrointestinal tract, papers on NO over the last two decades is a testament to respiratory and cardiovascular systems, as well as the CNS. the key physiologic and pathophysiologic roles that have The first new medicines to modulate the NO pathway have been attributed to this molecule. also been developed for male erectile dysfunction. The wealth of knowledge surrounding this molecule is represented by a variety of excellent reviews that provide a detailed account of the molecular and cellular effects of CONTROL AND REGULATION OF this agent (see Forstermann et al. [12], Ignarro [22]). The NITRIC OXIDE PRODUCTION aim of this manuscript is to provide a brief overview of how NO is generated by enzyme systems and how it can A schematic representation of the steps involved in the en- produce its biological actions with respect to its potential zymatic production of NO is shown in Figure 15-1.