Wrongful Convictions in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three, Four, Five Civil Liberties Groups Emerge in WA

Chapter 8 – Western Australia Three, four, five civil liberties groups emerge in WA The first mention of a civil liberties body in Perth came in an article in a local daily newspaper in September 1936: “The establishment of a Council of Civil Liberties in Perth was advocated yesterday by Mr. C. Bader (sic), readers’ counsellor under the adult education scheme of the University of Western Australia. Mr. Badger made the suggestion when discussing the action of the Customs Department in seizing 17 books from the Perth Literary Institute last week. “In view of the general tendency to interfere with the free circulation of books, and especially the tendency of the Federal Government to devolve its powers to irresponsible departments, said Mr. Badger, one felt there was a great need for a body in Perth affiliated to or parallel with the Council of Civil Liberties in Melbourne. This council, in its own way, was a development of the Council for Civil Liberties in England, whose president was Mr. E. W. Forster, the author of ‘Passage to India’. “It was a saddening fact that the battle for liberty, which people were apt to regard as having been won for them by their ancestors, had to be fought anew in each generation. “Despite the ample powers which governments had to suppress overt sedition and treachery, continued Mr. Badger, democratic governments still found it necessary to pass Acts like the Crimes Act, which were contrary to the whole tradition of British law and justice.” 1 Badger (photo), then just starting his career, went on to become the first Director of the Council of Adult Education in Victoria, a position he held until 1971. -

University of Canberra Matthew Ricketson The

Ricketson Writing interior monologues University of Canberra Matthew Ricketson The perils of writing interior monologues in narrative journalism Abstract: The interior monologue is perhaps the most controversial element of what is variously called narrative journalism, literary journalism, creative non-fiction or narrative non-fiction. Many practitioners and critics argue it is impossible to accurately convey a person’s innermost thoughts and feelings while some say that it is possible, if difficult. A small minority are unconcerned by any issues that may arise in journalists and other non-fiction writers writing interior monologues for the subjects of their stories. There is certainly no consensus on the issue. This paper examines what it is about the interior monologue that makes it so contentious. It draws on a review of contemporary practice and criticism, including an analysis of views offered by 19 leading practitioners interviewed by American scholar Robert Boynton and on interviews conducted by this paper’s author with leading Australian practitioners: John Bryson, Helen Garner, Chloe Hooper, Malcolm Knox, David Marr and Margaret Simons, and on analysis of the work of another, Estelle Blackburn. This review of contemporary practice is presented as suggestive rather than conclusive. It finds only seven of the 26 practitioners have written interior monologues. Biographical note: Dr Matthew Ricketson is an academic and journalist. He has worked in the Australian news media, at The Australian newspaper, Time Australia magazine and, most recently, as Media and Communications editor for The Age. He ran the journalism program at RMIT between 1995 and 2006 and in 2009 was appointed inaugural professor of journalism at the University of Canberra. -

Estelle Blackburn

EVENING SEMINAR BUTTONHOLING JUSTICE: THE STORY BEHIND BROKEN LIVES WITH ESTELLE BLACKBURN, JOHN BUTTON & TONY COOKE 24 November 2003, 7.30 pm, Niche Lotteries House, Hospital Ave, Nedlands (cnr Hospital Ave & Aberdare Rd, near St John Ambulance depot) Estelle Blackburn OAM is a Perth journalist and the author of Broken lives, the book that exposed an injustice and led to last year’s quashing of John Button’s 1963 manslaughter conviction. Estelle’s 10 year long justice crusade also brought her the prestig- ious Order of Australia and the Golden Walkley Award for journalism. Her book won the Ned Kelly Award for the best true crime story in 2001 and the WA Premier’s Award for non fiction in 1999. Estelle will speak about the events that prompted her interest in John Button’s case and how she maintained her determination to see it through. It is a compelling story about miscarriage of justice, perserverance and the impact on the lives of many people, including 11 unknown victims of attempted murder. John Button was convicted in 1963 for the hit and run killing of his 17 year old girlfriend Rosemary Anderson and for which he served five years in prison and a further five years on strict parole. Rosemary’s death occurred during a tumultous time in Perth with a series of murders by Eric Edgar Cooke, who was convicted and hung for these crimes. In 2002 the Court of Criminal Appeal quashed John Button’s conviction, largely as a result of the research for Estelle’s book,. In 2003 John Button was awarded $460,000 as compensation for his wrongful conviction and imprisonment for Rosemary’s death. -

Estelle Blackburn

Estelle Blackburn Speaker, Author, Walkley Award winning journalist Estelle Blackburn took on the justice system and, against all odds, rectified two grave injustices, demonstrating the power of an individual to alter history and improve society at a fundamental level. Now based in Canberra, Estelle is a former Perth journalist who has worked for The West Australian and the ABC, various W.A. Government ministers and a Premier. She gave up full-time work and spent six years researching and writing the book Broken Lives, published in 1998. Estelle’s book exposed an injustice which led to the 2002 and 2005 exonerations of John Button and Darryl Beamish, who had been convicted of murder in the 1960s, and created history as the longest standing convictions to be overturned in Australia. Her unfunded, determined sleuthing unearthed fresh evidence that prompted the Attorney General to allow the men new appeals after they had lost a combined total of seven Appeals in the 60s. Coming across the story by chance and persisting with it turned Estelle’s life around. Here was a courageous woman who without a second thought impoverished herself to fight the cause for strangers. With no legal training and armed only with extraordinary qualities of courage and determination, she took on the system and won. Because of her vision, hard work and self-sacrifice the justice system may have been set on a truer course. This work won her an Order of Australia medal in the 2002 Queens Birthday Honours List for her service to the community through investigative journalism. She has also won journalism’s highest honour, a Walkley Award for the Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism, the Perth Press Club Award, Western Australia’s Clarion Award, the Premier’s Award for non-fiction, the Australian Crime Writers’ Award for best true crime, and a scholarship to undertake a PhD in journalism at Murdoch University. -

Electronic Document

GriffithREVIEW47.indb 1 21/01/2015 3:43 pm Praise for Griffith Review ‘Essential reading for each and every one of us.’ Readings ‘A varied, impressive and international cast of authors.’ The Australian ‘Griffith Review is a must-read for anyone with even a passing interest in current affairs, politics, literature and journalism. The timely, engaging writing lavishly justifies the Brisbane-based publication’s reputation as Australia’s best example of its genre.’ The West Australian ‘There is a consistently high standard of writing: all of it well crafted or well argued or well informed, as befits the various genres.’ Sydney Review of Books ‘This quarterly magazine is a reminder of the breadth and talent of Australian writers. Verdict: literary treat.’ Herald Sun ‘Griffith Review editor Julianne Schultz is the ultra-marathoner of Australian cultural life.’ Canberra Times ‘At a time when long form journalism is under threat and the voices in our public debate are often off-puttingly condescending, hectoring and discordant, Griffith Review is the elegant alternative.’ Booktopia Buzz ‘Griffith Review is a consistently good journal. There is some terrific writing on display as well as variety and depth to the issues being grappled with.’ The Age ‘Australia’s most important literary essay magazine.’ Courier-Mail ‘At once comfortable and thought-provoking, edgy and familiar, [it] will draw the reader through its pages.’ Australian Book Review ‘Griffith Review is a wonderful journal. It’s pretty much setting the agenda in Australia and fighting way above its weight… You’re mad if you don’t subscribe.’ Phillip Adams ‘Once again, Griffith Review has produced a stunning volume of excellent work. -

Reflections While Researching Journalism and the Claremont Serial Killings

Coolabah, Nr 29, 2021, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians i Transnacionals / Observatory: Australian and Transnational Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Enigma of the Dark: Reflections while Researching Journalism and the Claremont Serial Killings Mary-Anne Romano Curtin University WA [email protected] Copyright© 2021 Mary-Anne Romano. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged, in accordance with our Creative Commons Licence. Abstract. After almost 25 years of mass media coverage on the Claremont Serial Killings, Perth audiences were informed in December 2020 that Bradley Robert Edwards would serve two life sentences for murdering two of the young women. This article draws on interviews with journalists to discuss media practices in the case that shocked Perth while shaping audience understandings of women as victims. The article describes how the term ‘serial killer’ came into use to bolster the importance of Western Australian news; how the status and resources of victim’s family influenced media coverage and, consequently, the police investigation; and, how the position of a journalist as an unbiased observer became untenable in the case. Keywords: Claremont Serial Killings; journalism as ritual; media coverage 17 Western Australia tends not to be a place where people come by accident. It is a conscious decision; whether it is to be with family, a long holiday, a place to work or in more recent times, to live life without the constraints of masks, lockdowns and the constant rhetoric of life during a pandemic. -

21 October, 1964.) 1747

[Wednesday. 21 October. 1964.1 141743 Progress page Progress reported and leave given to sit QUESTIONS ON NOTICE--coaiinsed again, on motion by The Hon. L. A. Logan Drudge "Sir James Mitchell "- (Minister for Local Government). Future Job .. 0.147 Period of Lay-off and Crew'ihid Off 1747 adjourned at 10.58 p.m. Education- House Bellevue State School :Provision of Staff Room.. ....... ... .-.. 1752 Hi1gh Schools : Ground Improvements 1747 Kindergartens :Government Subsidy for New Buildings .. ...1746 Muresk Agricultural College- Canteen : Sale of Cigarettes and Tobacco..........1752 Expulsion of Students:, Reasons.... 1752 Iti1rnidiativc Nm'eniblg Southern Cross State School : Tend- Wednesday, the 21st October, 1964 ens and Date of Completion .... 1744 Fertiliser- CONTENTS Fertilisers and Insecticides : Govern- Page ment Control over Aerial Spraying 1750 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT- Potash from Chandler- "Four Corners"1 Presentation of Eric Tonnage Recovered and Treated, Edgar Cooke Case ... .. 1762 and Market Value .. ...1744 Treatment Plant..............1744 CLOSING DAYS OF SESSION- Superphosphate Works at Esperanee-- Standing Orders Suspension.......1755 Establishment Cost and Capacity .... 1751 Financial Arrangements for Estab- BILLS- lishment ..... ............. 1751 Bibra Lake-Arinadale Railway Discon- Flour : Purchases by Government Institu- tinuance and Land Revesiment Bill- tIons--Quantity and Suppliers ........ 1747 Returned ... .. .. .. .. 1754 Clean Air Bill-Returned 1754 Health- Country Towns Sewerage Act Amendment Dental Treatment:- Facilities f or Bill-3r.............1756 Juveniles at Fremantle .... .... 1745 Electoral Act Amendment Dill-3r....1756 "P11l, The" :Availability and Cost 1745 Fremantle Harbour Trust Act Amendment Toilet Facilities- Bill-Returned .... ........... 1754 Availability at Surgeries ... 11749 Licensing Act Amendment Bill- Suburban Stations : Closure- Intro ; Ir .. .. .. 1755 Health Department's Approval Real Property (Foreign Governments) and Alternative Facilities ... -

14 September 2015 Michael Inman in the Canberra Times Reported “David Eastman to Sue ACT for Wrongful Imprisonment”

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge David Eastman Homepage This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles On 14 September 2015 Michael Inman in the Canberra Times reported “David Eastman to sue ACT for wrongful imprisonment” David Harold Eastman is suing the ACT government for wrongful imprisonment. An ACT Supreme Court suit alleges Eastman is eligible for compensation under the Human Rights Act. Attorney-General Simon Corbell confirmed he was aware of the litigation, but declined to comment on the case as it was before the courts. Lawyers have previously speculated that Eastman could be eligible for millions of dollars in compensation if he were to pursue a payout. Eastman spent 18 years, nine months, and 12 days (6860 days) behind bars for the murder of Australian Federal Police Assistant Commissioner Colin Winchester in 1989. Last year, an inquiry found his 1995 trial had been a miscarriage of justice, and the full bench of the ACT Supreme Court subsequently quashed his conviction. Canberra prosecutors intend to retry Eastman, but he has launched a stay application to halt the case – on the grounds he will not be able to get a fair hearing – before it can go before a jury. The stay application is listed to be heard before Acting Justice David Ashley, QC, in February. Court papers, filed by Eastman's lawyers, Ken Cush and Associates, last week, said the civil claim came as a result of their client's unlawful detention and wrongful conviction. It alleged the former Treasury official's imprisonment caused him deprivation of liberty, lost income, to suffer mental harm, damage to his reputation, and he had expended legal cost and time in fighting to reverse his conviction. -

Eric Edgar Cooke: What Makes a Serial Killer?

By Estelle Blackburn, who, in research for her book, Broken Lives, had access to a serial killer’s medical, legal, police and prison files and interviewed two psychiatrists and a psychologist who had dealt with him. Ms Blackburn is a member of CLA. This article appeared first in The West Australian – Go to article Eric Edgar Cooke: What makes a serial killer? Eric Edgar Cooke was a perfect fit for the serial killer type identified by criminal profilers. He was physically and emotionally abused as a child in a dysfunctional family, he escaped through disassociation and fantasy, sought to boost his low esteem through self- aggrandisement, raged against the society that ostracised him and he sought revenge, power and control through violent acts starting with arson and escalating to power over life and death. Cooke was born in February 1931 to a violent, alcoholic teenage father who loathed at first sight the son born with the facial deformity of a cleft palate and cleft lip. Eric had a misshapen mouth and bad mumble, surgery and speech therapy not in those days able to remedy what was called a hare lip, as it can today. He was subjected to daily beatings from his father using his fists, belts and sticks, as well as such general neglect and emotional cruelty as to leave him in no doubt that his father didn’t want him. His mother also suffered at her husband’s brutality, living in fear and poverty, working to raise him and two younger daughters on her meagre kitchenhand and cleaning wages, her husband drinking all he earned as a motor spare parts salesman. -

![[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 Using the System on December 31](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1420/tuesday-10-november-1998-2973-using-the-system-on-december-31-5351420.webp)

[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 Using the System on December 31

[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 using the system on December 31 1998 to coincide with amendments to the Public Sector Management (Review Procedures) Regulations 1995. Similar errors therefore should not occur in future. I have advised the relevant Ministers. The letter is signed, "Don Saunders, Commissioner for Public Sector Standards, November 4, 1998". [See paper No 339.] SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Final Report, Tabling Hon Tom Stephens (Leader of the Opposition) presented the final report of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia, and on his motion it was resolved - That the report do lie upon the Table and be printed. [See paper No 384.] Papers, Tabling HON TOM STEPHENS (Mining and Pastoral - Leader of the Opposition) [3.44 pm]: I seek leave to table papers of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia. By way of explanation to you, Mr President, and through you to the Leader of the Government, he will be familiar with this seeking of leave because he sought similar leave in similar circumstances for a committee that did some overseas work on an unrelated issue. Hon N.F. Moore: You do not have to talk me into it. Hon TOM STEPHENS: Okay. I have here a substantial number of documents which I hope the House will see fit to allow to lie on the Table of the House so that they may be accessed by the public. The committee has been particularly privileged in the work it undertook. The Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia has also directed me to present papers which the committee collected on its trip to Canada during July of this year. -

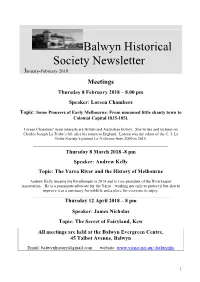

Newsletter Jan-Feb 2018 Final

Balwyn Historical Society Newsletter January-February 2018 Meetings Thursday 8 February 2018 – 8.00 pm Speaker: Loreen Chambers Topic: Some Pioneers of Early Melbourne: From unnamed little shanty town to Colonial Capital 1835-185l. Loreen Chambers’ main interests are British and Australian history. She writes and lectures on Charles Joseph La Trobe’s life after his return to England. Loreen was the editor of the C. J. La Trobe Society’s journal La Trobeana from 2009 to 2015. ___________________________________________________________________ Thursday 8 March 2018 -8 pm Speaker: Andrew Kelly Topic: The Yarra River and the History of Melbourne Andrew Kelly became the Riverkeeper in 2014 and is vice-president of the Riverkeeper Association. He is a passionate advocate for the Yarra – working not only to protect it but also to improve it as a sanctuary for wildlife and a place for everyone to enjoy. _____________________________________________________________________ Thursday 12 April 2018 – 8 pm Speaker: James Nicholas Topic: The Secret of Fairyland, Kew All meetings are held at the Balwyn Evergreen Centre, 45 Talbot Avenue, Balwyn Email: [email protected] website: www.vicnet.net.au/~balwynhs 1 A Word from the President Hello, I hope you all had a happy time with family and friends during the festive season and that you have renewed energy for exploring our history. We have an interesting program in place until our mid- year break in July. I would like to thank all the volunteers who have offered their help during our meetings. We could not manage without you as our committee is very small and it is not always possible for all of them to attend every meeting. -

The Suburbs of Hell

The Suburbs of Hell First Published - Secker & Warburg (London), Heinemann (Australia) 1984. Security is a fragile thing, as the people of the little medieval town of Old Tornwich soon find out. Against a relatively peaceful background, a series of apparently senseless, motiveless murders take place. The murders seem to be the work of a lunatic: the Tornwich Monster as the local papers call him. An epidemic of violence without apparent cause slices open the texture of Tornwich life, and sets it unravelling. Suspicion itself turns out to be a fatal infection. Afterword by Michelle de Krester: His eyes are on the one eye of the rifle. His mouth splits open his brown beard. He throws up a hand, palm outward, in an unwilled, futile gesture toward of death. A killer is hounding the seaside town of Old Tornwich. Residents are gripped with fear and suspicion, and the finger of blame is pointed in all directions. But the bodies keep falling and the crimes remain unsolved, the culprit at large. No mere whodunit, The Suburbs of Hell - its story inspired by a real-life serial killer - is a profoundly disturbing psychological drama with a devastating conclusion, the final work of one of Australia’s greatest writers. The Suburbs of Hell In the quiet seafaring town of Tornwich, little goes unnoticed. Neighbourhood gossip spreads like wildfire, leaving few skeletons in closets. But late one night a man is shot dead in his home. A short time later another body is discovered. The town is gripped by fear. The finger of blame is pointed in all directions.