The Evolution of the Melbourne Beth Din Chaim Cowen Abstract This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting Your Get At

Getting your Get at www.gettingyourget.co.uk Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers. by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB The website at www.gettingyourget.co.uk is sponsored by Barnett Alexander Conway Ingram, Solicitors, London 1 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Dedicated to the loving memory of Sharon Faith’s late parents, Maisie and Dr Oswald Ross (zl) and Deanna Levine’s late parents, Cissy and Ellis Levine (zl) * * * * * * * * Published by Cissanell Publications PO Box 12811 London N20 8WB United Kingdom ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 © Sharon Faith and Deanna Levine First edition: February 2002 Second edition: July 2002 Third edition: 2003 Fourth edition: 2005 ISBN 0-9539213-1-X Fifth edition: 2006 ISBN 0-9539213-4-4 Sixth edition: 2008 ISBN 978-0-9539213-5-5 2 www.gettingyourget.co.uk Getting your Get Information for Jewish men and women in England, Wales and Scotland about divorce according to Jewish law with articles, forms and explanations for lawyers by Sharon Faith BA (Law) (Hons) and Deanna Levine MA LLB List of Contents Page Number Letters of endorsement. Quotes from letters of endorsement ……………………………………………………………. 4 Acknowledgements. Family Law in England, Wales and Scotland. A note for the reader seeking divorce…………. 8 A note for the lawyer …………….…….. …………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 Legislation: England and Wales …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 Legislation: Scotland ………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 1. Who needs a Get? .……………………………………………………………………………….…………………... 14 2. What is a Get? ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 3. Highlighting the difficulties ……………………………………………………………………………….………….. 15 4. Taking advice from your lawyer and others ………………………………………………………………………. -

About the London Beth Din Published on United Synagogue (

About the London Beth Din Published on United Synagogue (https://www.theus.org.uk) About the London Beth Din Jewish life in England goes back almost 1000 years. It is believed that the first Jews were brought over from Normandy by William the Conqueror in 1066; there is reference to Jews in Oxford as early as 1075 and the Doomsday Book of 1086 records the Jew Mennasseh owning land in Oxfordshire. Several Baalei Tosafot (commentators) lived in England including R.Yaakov Mi’Orleans, (martyred in London at the coronation of Richard the Lionheart in 1189), R. YomTov Mi’Yoigny, author of Omnam Kein recited on Yom Kippur Maariv (martyred in the York massacre of 1190) and the R'i Mi’Londri, who is mentioned in the Remo in Hilchot Pesach (Siman 473 Sif 76) as recommending that the Hagadah be recited in the vernacular. In 1290, however, Jewish life in England came to abrupt end when the Edict of Expulsion was proclaimed by King Edward I, resulting in the banishment of the entire Jewish population from Britain. The Edict was issued on 18th July, which fell on Fast of Tisha B'Av. England remained "Yudenrein" free of Jews until 1656 when R. Menashe Ben Israel successfully petitioned Oliver Cromwell to allow the readmission of Jews. It is said that Menashe Ben Israel pressed Oliver Cromwell on the grounds that England -Angleterre- was one of the four "angles" of the earth referred to in the prophecies of the ingathering of the exiles, and thus resettlement would hasten the coming of the Messiah! Within only 50 years the offices of the Chief Rabbi and the London Beth Din came into being to provide a central religious authority for Jewish communities in London and throughout the United Kingdom - a role reflected in the London Beth Din's official title "D'Kehila Kedosha London Bet Din Vehamedina" - The Beth Din of London and the Country. -

Kosher Certificate

COURT OF THE CHIEF RABBI BETH DIN, LONDON Dayan Ch. Ehrentreu, KASHRUT DIVISION - KLBD Emeritus Rosh Beth Din & Consultant Dayan Rabbi J. D. Conway, Director Dayan M. Gelley, Rosh Beth Din Dayan I. Binstock Dayan S. Simons KOSHER CERTIFICATE Date Cover Page 08.05.2021 Company Code: 5780 26th Iyar 5781 THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT Certificate Number: 49755 IS A KLBD – LONDON BETH DIN CERTIFIED COMPANY AUTHORIZED TO PRODUCE KOSHER PRODUCTS FROM THEIR PRODUCTION SITE LISTED BELOW, AS PER THE ITEMS LIST AND THE RESTRICTIONS SPECIFIED IN THE ATTACHED DOCUMENT This certificate is valid until 08 May 2022 and is then subject to renewal. Rabbi Jeremy Conway Dayan Menachem Gelley Head Office: Kashrut Division, 305 Ballards Lane, London, N12 8GB, United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 20 8343 6246 Fax: +44 (0) 20 8343 6254 eMail: [email protected] Web: www.klbdkosher.org COURT OF THE CHIEF RABBI BETH DIN, LONDON Dayan Ch. Ehrentreu, KASHRUT DIVISION - KLBD Emeritus Rosh Beth Din & Consultant Dayan Rabbi J. D. Conway, Director Dayan M. Gelley, Rosh Beth Din Dayan I. Binstock Dayan S. Simons KOSHER CERTIFICATE Date Page Number: 1 of 2 08.05.2021 Company Code: 5780 26th Iyar 5781 Certificate Number: 49755 The following products manufactured by BDF NATURAL INGREDIENTS SL, Spain at the factory site listed below are Kosher certified by the London Beth Din Kashrut Division (KLBD) for year round use when bearing the kosher logo and according to the Kosher status below. BDF Natural Ingredients SL Carrer Cuirol, 8, Polígon Industrial Pla de l'Illa Quart Girona 17242 Spain -

The KA Kosher Certification

Kosher CertifiCation the Kashrut authority of australia & new Zealand the Ka Kosher CertifiCation he Kashrut Authority (KA) offers a wide range of exceptional T Kosher Certification services to companies in Australia, New Zealand and Asia. A trusted global leader in the field of Kosher Certification for more than a century, The Kashrut Authority is deeply committed to aiding clients on their kosher journey, helping to realise a profitable and long lasting market outlet for many and varied products. Accessing the kosher market offers a competitive edge, with vast potential on both a local and international scale. The Kashrut Authority believes in keeping the process simple, presenting a dedicated team and offering cutting edge technological solutions—The Kashrut Authority looks forward with confidence. 2 welCome n behalf of the entire KA Team, I am delighted to welcome O you to The Kashrut Authority, a dynamic organisation that has been instrumental in bringing kosher products to the people for more than a century. Our name, The Kashrut Authority, embodies who we are and what we do: kashrut is simply the Hebrew word for kosher, and we truly are authoritative experts in this field. Our KA logo is a proven trust–mark that consumers hold in the highest regard and we have extensive experience in helping clients with Kosher Certification for an incredible array of products. Our vast knowledge and experience in the kosher field helps each client on their kosher journey. Many of our clients have received KA Kosher Certification and, under the Kashrut Authority’s guidance, have been incredibly successful at both a local and global level. -

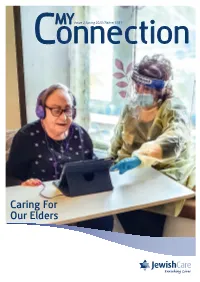

Caring for Our Elders MESSAGE from OUR PRESIDENT and CEO INBOX

CMYonnIssue 2 Spring 2020/Tishreiecti 5781 on Caring For Our Elders MESSAGE FROM OUR PRESIDENT AND CEO INBOX The past few months have been I still have tears in my eyes as I write unprecedented, to say the least, this email - I am just blown away by your causing far-reaching distress thoughtfulness, support and care. Words and destruction on the lives of cannot adequately describe how much many individuals and families. Jewish Care’s offer means to me, I am so Australia’s extraordinary beyond grateful. Thank you so much. From uninterrupted run of economic the first time we spoke your sincerity and growth has experienced a most genuine concern for me and my children’s dramatic interruption. We wellbeing has been so heart-warming and are now officially in a severe I wanted to thank you again for just being Susie Ivany OAM, President Bill Appleby, CEO recession after 29 years of there to listen on the other end of the prosperity, impacting hundreds of thousands of people and communities across this line, simply taking the time to call, and for country. The effects have amplified pre-existing disadvantage in our community, arranging the food deliveries. adversely affected the most vulnerable, whilst also impacting individuals and ~ Anonymous families who have never experienced such despair. This viral tsunami has compelled our governments to act quickly to protect those most negatively impacted through a Share your feedback about range of various supports. Nevertheless, these supports will be wound back over the our services by emailing next 6 months and we must be ready as a community to stand up and respond. -

Shelach Lecha Shabbat Mevarechim

17 June 2017 23 Sivan 5777 Shabbat ends London 10.27pm Jerusalem 8.29pm Volume 29 No. 38 Shelach Lecha Shabbat Mevarechim. Rosh Chodesh Tammuz is next Shabbat and Sunday Artscroll p.798 | Hertz p.623 | Soncino p.860 In memory of Harav Yisrael ben Harav Uriah “They arrived at the Valley of Eshkol and cut from there a vine with one cluster of grapes, and bore it on a double pole, and of the pomegranates and of the figs” (Bemidbar 13:23). 1 Sidrah Summary: Shelach Lecha 1st Aliya (Kohen) – Bemidbar 13:1-20 20 will die in the desert over the next 40 years. God tells Moshe to send spies into Cana’an (later The spies die in a plague, except Yehoshua the Land of Israel), one from each tribe. The and Calev. Moshe tells the nation about the names of the spies are listed. One of them is 40 year decree and they mourn. Despite Moshe’s Hoshea, whose name Moshe changes to discouragement, a section of the people attempt Yehoshua (Joshua). Moshe instructs the spies to enter the Land but are brutally thwarted by the to enter the Land from the south, look at its Amalekites and Cana’anites. nature and check the strength of its inhabitants. God tells Moshe to instruct the nation that when Point to Consider: why did Moshe change they bring animal offerings, these should be Yehoshua’s name? (See Rashi to 13:17). accompanied by a bread meal offering (mincha) and a wine libation (nesech). 2nd Aliya (Levi) – 13:21-14:7 Question: why did the punishment last for 40 The spies enter the Land. -

ARCHIVE of AUSTRALIAN JUDAICA HOLDINGS 1983–2012 Compiled

Monograph No. 16 ISSN 0815-3850 ARCHIVE OF AUSTRALIAN JUDAICA HOLDINGS 1983–2012 Compiled by Marianne Dacy Project director Suzanne Rutland Published by the Archive of Australian Judaica, University of Sydney Library, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INDIVIDUAL COLLECTIONS - Bibliographical 1–25 Resources Name Index Collection (by shelf list) 26 Subject Index (by shelf list) 27 IIA ORGANISATIONAL ARCHIVES 28 IIB COMMUNITY ARCHIVES 39 III PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION 41 IV AUSTRALIAN YIDDISH LITERATURE 42 V SUBJECT FILES 44 VI TAPE COLLECTIONS 53 VII CURRENT PERIODICALS (JEWISH COMMUNITIES) 54 VIII CURRENT PERIODICALS (JEWISH ORGANISATIONS) 54 IX CURRENT ANNUAL REPORTS 56 X THESES AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS 57 XI EPHEMERA 59 XII PERIODICALS (ASSEMBLED) 65 XIII VIDEOS 2 INDEX OF NAMES OF INDIVIDUALS (by shelf list) COLLECTIONS (by shelf list) Shelf List) AARON, Aaron 30 PATKIN, Ben Zion 20 APPLE, Raymond Rabbi 73 PEARL, Cyril 18 ABRAHAM, Vivienne 59 PIZEM, Sam 69 BAER, Werner 25 PORUSH, Israel 54 BERG, Maurice de 16 RICH-SCHALIT, Ruby 40 BERGER, Theo 22 ROSENBLUM, Myer 52 BISCHOPSWERDER, Boaz 54 RUBINSTEIN, W. 63 BOAS, Harold 37 SCHWARTZ, Agnes 33 BRAHAM, Mark 8 SHEPPARD, Alec W. 9 CAPLAN, Leslie 29B SOLVEY, Joseph 31 CAPLAN, Sophie 29A SPITZER, Sam 65 CHER, Ivan 43 STRICKER, Beata 60 COHEN, Ilana 58 STRICKER, Henry 61 COHEN, David 35 STONE, Julius 58 CROWN, Alan 44 SYMONDS, Ken 48 DAVIS, Richard 74 TAMARI, Moshe 55 EVEN, Arie 11 WATSON, Leo 66 FABIAN, Alfred 46 YOUNG, Joy 51 FALK, Leib Aisack 14 ZBAR, Abraham 53 FEHER, Yehuda 1 FINK, Lote 80 GOLDBERG, Solomon 15 GREGORY, George 34 GUTMAN, Margaret 49 HAMMERMAN, Bernhard 28 HELFGOTT, Eva 24A HELFGOTT, Sam 24B HERTZBERG, Leopold 42 HONIG, Eliyahu 39 ISAACS, Maurice 3 JAMES, Henry 21 JOEL, Asher 62 JOSEPH, Max 2 KAIM, Ilana 58 KARPIN, Sam 4 KATZ, Dr. -

1998-05-17 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

-----------~~~--~~~ ·- -~ .. -I COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES FRIDAY, SATURDAY AND SUNDAY, MAY 15,16 AND 17,1998 JOYCE CENTER UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME NOTRE DAME, INDIANA ---1\NJ Events of the Weekend FRIDAY, MAY 15 Noon RESIDENCE HALLS available for check-in to parents and guests (Registration and payment required.) 3-4 p.m. COLLEGE OF ARTS AND LETTERS HONORS CONVOCATION Washington Hall (Reception to follow - LaFortune Stt(dent Center Ballroom) 4p.m. CHORALE CONCERT · University of Notre Dame Chorale - Basilica of the Sacred Heart 6:30p.m. LAWN CONCERT University Concert Band - Main· Building Mall (Incleinent weather location: Band Building) 6:30-8 p.m. BUFFET-STYLE DINNER North Dining Hall . - -~ - .. (Tickets must be purchased in advance.) 8-10 p.m. GRADUATE SCHOOL RECEPTION by the Vice President for Graduate Studies and Research, for degree candidates in The Graduate School and their families and guests - Center for Continuing Education Auditorium 9 p.m. -1 a.m GRADUATION DANCE Joyce Center - North Dome SATURDAY, MAY 16 9:30a.m. ROTC COMMISSIONING Joyce Center - South Dome 10 a.m. SENDING CEREMONY FOR STUDENTS DOING VOLUNTEER SERVICE AFTER COMMENCEMENT Washington Hall (Reception to follow - Center for Social Conccms) F1iday, Saturday and Sunday, May 15, 16 and 17, 1998. Except when noted, all ceremonies and activities arc open 10:30 a.m. and 11:30 a.m. to the public and tickets are not required. GUIDED MUSEUM TOUR The Snite Museum of Art (45 minutes) 11:30 a.m. 6:45-8 p.m. PHI BETA KAPPA INSTALLATION GRADUATION DINNER DeBartolo Hall Audit01iwn - Room 101 Joyce Center - North Dome and N011h Dining Hall (Initiates are requested to arrive at 11 a.m.) (Tickets must be purchased in advance per infonnation and ticket procurement procedures.) Noon -1 p.m. -

For 2021 Victoria`S Organisations List Click Here

1 The information contained in this directory has been provided by the organisations listed. The JCCV takes no responsibility for the accuracy of the information provided by the organisations, or lack thereof. # ACCESS INC Partners with young adults with disabilities to achieve goals CEO: Sharon Malecki T: 9272 5603 LJLA 304-306 Hawthorn Rd, Caulfield Sth 3162 PO Box 2401, Caulfield Junction 3161 [email protected] www.accessinc.org.au ADASS ISRAEL CONGREGATION 24 Glen Eira Ave, Ripponlea, 3183 T: 9523 1204, 9528 5632; Office: T: 9528 3079 [email protected] Adass Israel School 10-12 King St, & 86-90 Orrong Rd, Elsternwick 3185. Kindergarten-high school [email protected]; T: 9523 6422 Admin: Mr Moshe Nussbacher: [email protected] Adass Israel Chevra Kadisha 712 Princes Hwy, Springvale T: 9528 5424 Parlour: 16 Horne St, Elsternwick 3185 Caulfield-Adass Israel Mikvah 9 Furneaux Gve, East St Kilda 3183 T: 9528 1116 Ring for appointment. AIA – ASSOCIATION OF ISRAELIS IN AUSTRALIA www.ausraelim.com.au Pres: Eitan Drori 0414 235 567 Sec: Dr Ran Porat 0404 642 833 AISH AUSTRALIA Rabbi Andrew Saffer T: 1300 741 613 [email protected] www.aish.org.au 46 Balaclava Rd, St Kilda East Vic 3183 2 ALEPH MELBOURNE A support & advocacy group for people of diverse sexual orientation, gender identity and intersex status. [email protected] Unit 2/24 Winbirra Pde, Ashwood 3147 Michael Barnett T: 0417-595-541 www.aleph.org.au facebook.com/alephmelb ALIYAH CENTRE 306 Hawthorn Rd, Caulfield South 3162 T: 9272 5688 [email protected] ANTI-DEFAMATION -

The Rebbe's Sicha to the Shluchim Page 2 Chabad Of

1 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 כאן צוה ה’ את הברכה CommunityNewspaper פרשת חיי שרה | כג' חשון , תשס”ט | בס”ד WEEKLY VOL. II | NO 4 NOVEMBER 21, 2008 | CHESHVAN 23, 5769 WELCOME SHLUCHIM! Page 3 HoraV HachossiD CHABAD OF CHEVRON REB AharoN ZAKON pAGE 12 THE REBBE'S SICHA TO THE SHLUCHIM PAGE 2 Beis Din of Crown Heights 390A Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, NY Tel- 718~604~8000 Fax: 718~771~6000 Rabbi A. Osdoba: ❖ Monday to Thursday 10:30AM - 11:30AM at 390A Kingston Ave. ☎Tel. 718-604-8000 ext.37 or 718-604-0770 Sunday-Thursday 9:30 PM-11:00PM ~Friday 2:30PM-4:30 PM ☎Tel. (718) - 771-8737 Rabbi Y. Heller is available daily 10:30 to 11:30am ~ 2:00pm to 3:00pm at 788 Eastern Parkway # 210 718~604~8827 ❖ & after 8:00pm 718~756~4632 Rabbi Y. Schwei, 4:00pm to 9:00pm ❖ 718~604~8000 ext 36 Rabbi Y. Raitport is available by appointment. ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ☎ Rabbi Y. Zirkind: 718~604~8000 ext 39 Erev Shabbos Motzoei Shabbos Rabbi S. Segal: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 39 ❖ Sun ~Thu 5:30pm -9:00pm or ☎718 -360-7110 Rabbi Bluming is available Sunday - Thursday, 3 -4:00pm at 472 Malebone St. ☎ 718 - 778-1679 Rabbi Y. Osdoba ☎718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 10:0am -11:30am ~ Fri 10:am - 1:00 pm or 4:16 5:17 ☎ 718 -604-0770 Gut Shabbos Rabbi S. Chirik: ☎ 718~604~8000 ext 38 ❖ Sun~Thu: 5:00pm to 9:00pm 2 CROWN HEIGHTS NewsPAPER ~November 14, 2008 The Vaad Hakohol REBBE'S STORY “When one tells a story about his Rebbe he connects to the deeds of the Rebbe” (Sichos 1941 pg. -

Twenty-Seventh Year the Jewish Publication Society of America

REPORT OF THE TWENTY-SEVENTH YEAR OF THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA 1914-1913 JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY 397 THE JEWISH PUBLICATION SOCIETY OF AMERICA OFFICERS PRESIDENT SIMON MILLER, Philadelphia FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT DR. HENRY M. LEIPZIGER, New York SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT HORACE STERN, Philadelphia TREASURER HENRY FERNBERGER, Philadelphia SECRETARY BENJAMIN ALEXANDER, Philadelphia ASSISTANT SECRETARY I. GEORGE DOBSEVAGE, Philadelphia SECRETARY TO THE PUBLICATION COMMITTEE HENRIETTA SZOLD, New York TRUSTEES DR. CYRUS ADLER 2 Philadelphia HART BLUMENTHAL J Philadelphia CHARLES EISENMAN 1 Cleveland HENRY FERNBERGER 3 Philadelphia DANIEL GUGGENHEIM * New York 3 JOSEPH HAGEDORN Philadelphia S. CHARLES LAMPORT ' New York EPHRAIM LEDERER * Philadelphia 2 DR. HENRY M. LEIPZIGER New York SIMON MILLER * Philadelphia MORRIS NEWBURGER ' New York JULIUS ROSENWALD * Chicago SIGMUND B. SONNEBORN 1 Baltimore HORACE STERN S Philadelphia SAMUEL STRAUSS * New York a HON. SELIGMAN J. STRAUSS Wilkes-Barre, Pa. 3 CYRUS L. SULZBERGER New York HON. MAYER SULZBERGER 2 Philadelphia 1 Term expires in 1916. > Term expires in 1917. 3 Term expires in 1918. 3 398 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK A. LEO WEIL2 Pittsburgh 1 HARRIS WEINSTOCK Sacramento EDWIN WOLF ' Philadelphia HONORARY VICE-PRESIDENTS 3 ISAAC W. BEHNIIEIM Louisville REV. DR. HENRY COHEN 2 Galveston Louis K. GTJTMAN * Baltimore REV. DR. MAX HELLER * New Orleans Miss ELLA JACOBS * Philadelphia S. W. JACOBS 3 Montreal 3 Louis E. KIKSTEIN Boston HON. JULIAN W. MACK 3 Chicago REV. DR. MARTIN A. MEYER 1 San Francisco 1 HON. SIMON W. ROSENDALE Albany, N. Y. 2 MURRAY SEASONGOOD Cincinnati HON. M. C. SLOSS 2 San Francisco REV. DR. JOSEPH STOLZ * Chicago HON. SIMON WOLF 3 Washington, D. -

The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship

Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 8 Article 3 2016 The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship James L. Kugel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kugel, James L. (2016) "The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship," Studies in the Bible and Antiquity: Vol. 8 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol8/iss1/3 This Forum is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in the Bible and Antiquity by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Irreconcilability of Judaism and Modern Biblical Scholarship James L. Kugel Thanks to the work of scholars of the Hebrew Bible over the last two centuries or so, we now know a great deal about how and when various biblical texts were composed and assembled; in fact, this has been the focus of much of modern biblical scholarship. One thing has become clear as a result. Our biblical texts are actually the product of multiple acts of rewriting. All our canonical books have been found to be, in some degree, the result of editorial expansion, rearrangement, and redaction introduced by various anonymous ancient scholars. This raises an important question about those ancient scholars. To put it bluntly: How dare they? If you, an ancient Israelite, believe that Scripture