The Egoist Vol. 2, No. 10 (October 1, 1915)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making the New: Literary Periodicals and the Construction of Modernism

Making the New: Literary Periodicals and the Construction of Modernism Peter Marks University of Sydney We are told that we live in a postmodernworld, experiencing unprecedented innovations, delights, and anxieties. Rather than rehearse these here, I want initially to touch brieflyon one theoretical attempt to make sense of this condition, one that definesPostmodernism in relation to its presumed antecedent, Modernism. I want to use this as a way of questioning the "monumental" view of literary Modernism, in which a massive landscape abounds with canonical texts carved by mythical giants: Joyce, Eliot, Woolf, Pound, Stein-the usual suspects. I do this by considering the role of literary periodicals in the construction, production, and initial reception of those texts. The later part of this discussion focuses on transition, the Paris-based journal of the 1920s and 1930s whose aspirations, pretensions, vigor and perilous existence typify the complex forces in play. I emphasize the point that while indi vidual periodicals consciously adopted distinct identities, they need to be understood collectively forthe vital functionsthey performed: they printed avant-garde work as well as advanced criticism and theory; acted as nurseries for experimental young writers, and as platformsfor the already-established; forged and maintained interna tional links between writers and groups; provided avant-garde writers with sophisti cated readers, and vice versa; and maintained an ipteractiveplurality of cultural dis course. Alive with the energy of experimentation, they register the fertile, complex, yet intriguingly tentative development of modem literature. In his inquisitive and provocative work, ThePostmodern Turn, lhab Hassan moves towards a concept of postmodernism by constructing a table of "certain schematic differences from modernism" (91). -

Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture

GENETIC JOYCE STUDIES – Issue 9 (Spring 2009) Early Sources for Joyce and the New Physics: the “Wandering Rocks” Manuscript, Dora Marsden, and Magazine Culture Jeff Drouin The bases of our physics seemed to have been put in permanently and for all time. But these bases dissolve! The hour accordingly has struck when our conceptions of physics must necessarily be overhauled. And not only these of physics. There must also ensue a reissuing of all the fundamental values. The entire question of knowledge, truth, and reality must come up for reassessment. Obviously, therefore, a new opportunity has been born for philosophy, for if there is a theory of knowledge which can support itself the effective time for its affirmation is now when all that dead weight of preconception, so overwhelming in Berkeley's time, is relieved by a transmuting sense of instability and self-mistrust appearing in those preconceptions themselves. — Dora Marsden, “Philosophy: The Science of Signs XV (continued)—Two Rival Formulas,” The Egoist (April 1918): 51. There is a substantial body of scholarship comparing James Joyce's later work with branches of contemporary physics such as the relativity theories, quantum mechanics, and wave-particle duality. Most of these studies focus on Finnegans Wake1, since it contains numerous references to Albert Einstein and also embodies the space and time debate of the mid-1920s between Joyce, Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. There is also a fair amount of scholarship on Ulysses and physics2, which tends to compare the novel's metaphysics with those of Einstein's theories or to address the scientific content of the “Ithaca” episode. -

A MEDIUM for MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY and AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997

A MEDIUM FOR MODERNISM: BRITISH POETRY AND AMERICAN AUDIENCES April 1997-August 1997 CASE 1 1. Photograph of Harriet Monroe. 1914. Archival Photographic Files Harriet Monroe (1860-1936) was born in Chicago and pursued a career as a journalist, art critic, and poet. In 1889 she wrote the verse for the opening of the Auditorium Theater, and in 1893 she was commissioned to compose the dedicatory ode for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Monroe’s difficulties finding publishers and readers for her work led her to establish Poetry: A Magazine of Verse to publish and encourage appreciation for the best new writing. 2. Joan Fitzgerald (b. 1930). Bronze head of Ezra Pound. Venice, 1963. On Loan from Richard G. Stern This portrait head was made from life by the American artist Joan Fitzgerald in the winter and spring of 1963. Pound was then living in Venice, where Fitzgerald had moved to take advantage of a foundry which cast her work. Fitzgerald made another, somewhat more abstract, head of Pound, which is in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Pound preferred this version, now in the collection of Richard G. Stern. Pound’s last years were lived in the political shadows cast by his indictment for treason because of the broadcasts he made from Italy during the war years. Pound was returned to the United States in 1945; he was declared unfit to stand trial on grounds of insanity and confined to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital for thirteen years. Stern’s novel Stitch (1965) contains a fictional account of some of these events. -

Imagism and Te Hulme

I BETWEEN POSITIVISM AND Several critics have been intrigued by the gap between late AND MAGISM Victorian poetry and the more »modern« poetry of the 1920s. This book attempts to get to grips with the watershed by BETWEEN analysing one school of poetry and criticism written in the first decade of the 20th century until the end of the First World War. T To many readers and critics, T.E. Hulme and the Imagists . E POSITIVISM represent little more than a footnote. But they are more HULME . than mere stepping-stones in the transition. Besides being experimenting poets, most of them are acute critics of art and literature, and they made the poetic picture the focus of their attention. They are opposed not only to the monopoly FLEMMING OLSEN T AND T.S. ELIOT: of science, which claimed to be able to decide what truth and . S reality »really« are, but also to the predictability and insipidity of . E much of the poetry of the late Tennyson and his successors. LIOT: Behind the discussions and experiments lay the great question IMAGISM AND What Is Reality? What are its characteristics? How can we describe it? Can we ever get to an understanding of it? Hulme and the Imagists deserve to be taken seriously because T.E. HULME of their untiring efforts, and because they contributed to bringing about the reorientation that took place within the poetical and critical traditions. FLEMMING OLSEN UNIVERSITY PRESS OF ISBN 978-87-7674-283-6 SOUTHERN DENMARK Between Positivism and T.S. Eliot: Imagism and T.E. -

View PDF Datastream

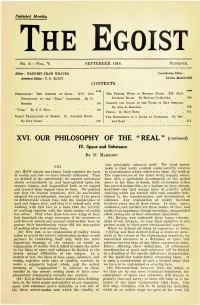

Published Monthly THE EGOIST No. 8.—VOL. V. SEPTEMBER 1918. SIXPENCE. Editor : HARRIET SHAW WEAVER Contributing Editor : Assistant Editor : T. S. ELIOT DORA MARSDEN CONTENTS PAGE PAOB PHILOSOPHY : THE SCIENCE OF SIGNS. XVI. OUR THE FRENCH WORD IN MODERN PROSE. XII. JEAN- RICHARD BLOCH. By Madame Ciolkowska . 108 PHILOSOPHY OF THE "REAL" (continued). By D. CHARITY AND GRACE IN THE WORK OF MAY SINCLAIR. Marsden ........ 101 By Jean de Bosschère . .109 " TARR." By T. S. Eliot 105 VISION. By Mary Butts 111 EARLY TRANSLATORS OF HOMER. II. ANDREAS DIVUS. THE MEDITATION OF A LOVER AT DAYBREAK. By Her By Ezra Pound . • . .106 bert Read 111 XVI. OUR PHILOSOPHY OF THE " REAL " (continued) IV. Space and Substance By D. MARSDEN time principally exhausts itself. The third motor- VIII mode is that newly evolved motor-activity relative (81) HOW closely our theory binds together the facts to symbolization which collectively form i the intellect. of reality and time we have already indicated. Time The supervention of the latter being happily coinci we defined as the potentiality for organic movement dent with a specialized development of the spatial slowly accumulated in, and impregnated upon, the power in the form of hands, their co-incident action organic tissues, and bequeathed both as to capital has proved responsible—in a fashion we have already and interest from organic form to form. We pointed described—for that unique form of activity called out that the human organism, with its mechanism realizing which has reacted with such amazing fruit- adapted for symbolization, brought with it the power fulness in the transformation and development of to differentiate simple time into the complexities of substance. -

Issues of Modernism: Editorial Authority in Little Magazines of the Avant Guerre

Issues of Modernism: Editorial Authority in Little Magazines of the Avant Guerre Raymond Tyler Babbie A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2017 Reading Committee: Brian Reed, Chair Leroy Searle Jeanne Heuving Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English © Copyright 2017 Raymond Tyler Babbie University of Washington Abstract Issues of Modernism: Editorial Authority in Little Magazines of the Avant Guerre Raymond Tyler Babbie Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Brian Reed, Professor Department of English Issues of Modernism draws from the rich archive of little magazines of the avant guerre in order to examine the editorial intervention that shaped the emergence of modernism in their pages. Beatrice Hastings of The New Age deployed modernist techniques both in her fiction and in her editorial practices, blurring the line between text and context in order to intervene forcefully in the aesthetic and political debates of her age, crucially in the ongoing debates over women’s suffrage. The first chapter follows her emergence as an experimental modernist writer and editor, showing how she intervened in the public sphere via pseudonyms and anonymous writing. When Roger Fry’s exhibition, Manet and the Post-Impressionists, became the scandal of the London art world in late 1910, she used the debate over its value as an impetus to write experimental fiction that self-consciously drew from post-impressionist techniques. She continued to develop and use these techniques through the following years. The second examines her career in 1913, during which she continued to develop her modernist fiction in counterpoint to her political interventions and satires. -

Louis K. Mackendrick TS ELIOT and the EGOIST

Louis K. MacKendrick T.S. ELIOT AND THE EGOIST: THE CRITICAL PREPARATION I T.S. Eliot is infrequently remembered as the last literary editor of the Egoist, a small avant-garde periodical with which he was associated from June 1917 until its expiry in December 1919. With the exception of the essay "Tradition and the Individual T alent" his other work for that little magazine has been largely overlooked. Yet a survey of Eliot's Egoist reviews, the form taken by his early criticism, indicates how his concern with tradition in literature reached the po int of formulation in his only maj or article for the journal. Because his role with t he Egoist was as a contributor rather than as an administrator, it is in this perspective that Eliot's writing as its Assistant Editor meri ts re consideration. Eliot secured his fi rs t editorial position throu gh the agency of Ez ra Pound. The Egoist was the re titled successor o f the New Freewoman (1 913), a fem ini st fortnigh tly com mandeered b y Pound as the principal English ou tlet for such Imagist poe ts as himsel f, "H.D." , Richa rd Aldington, and William Carlos Williams. With the change o f nam e in January 19l4 Aldington became its Assistan t Editor until his milita ry call-up in late 19 16. The Editor was Harriet Shaw Weaver, James J oyce's benefactress, who trusted Po und's judgement com pletely. Pound hungered for periodicals, but dissociated himself from Imagism when the movement was taken over by Amy Lowell and pursued hi s interests in Poetry (Chicago) and the Little R eview. -

Critical Survey of Poetry: British, Irish, & Commonwealth Poets

More Critical Survey of Poetry: British, Irish, & Commonwealth Poets Richard Aldington by Robert W. Haynes Other literary forms TABLE OF Richard Aldington established himself in the literary world of London as a CONTENTS youthful poet, but later in life he increasingly devoted his attention to prose Other literary forms fiction, translation, biography, and criticism. His first novel, Death of a Hero Achievements (1929), drew favorable attention, and it was followed in 1930 by Roads to Biography Glory, a collection of thirteen short stories. Aldington continued to publish Analysis fiction until 1946, when his last novel, The Romance of Casanova, appeared. Imagism The long poems Richard Aldington Bibliography (Library of Congress) From early in his career, Aldington was highly regarded as a translator. He translated Remy de Gourmont: Selections from All His Works (1929; 2 volumes) from French, The Decameron of Giovanni Boccaccio (1930) from Italian, Alcestis (1930) from classical Greek, and other works from Latin and Provençal. Aldington wrote biographies of the duke of Wellington (1943) and of Robert Louis Stevenson (1957), along with Voltaire (1925), D. H. Lawrence: Portrait of a Genius But . (1950), and Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry (1955), along with a substantial body of critical essays. Other miscellaneous works include Life for Life’s Sake: A Book of Reminiscences (1941) and Pinorman: Personal Recollections of Norman Douglas, Pino Orioli, and Charles Prentice (1954). Aldington also edited The Viking Book of Poetry of the English-Speaking World (1941). Achievements Despite Richard Aldington’s extensive publications in criticism and in a variety of literary genres, he remains inextricably associated with the movement known as Imagism, of which he was certainly a founding member, along with the American poets H. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tarr by Wyndham Lewis

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Tarr by Wyndham Lewis Tarr is a novel at war with itself, with tensions raging at not only the level of style and content, but at the level of the book itself in that it exists in a few versions, being altered and revised by Lewis as it suited his fancy and his temper and his ever-mutating world view, and so even subsequent editors have been at war in their attempts to produce a definitive version.3.4/5Ratings: 426Reviews: 32Tarr - Kindle edition by Lewis, Wyndham. Literature ...https://www.amazon.com/Tarr-Wyndham-Lewis-ebook/dp/B006J2YLP8Tarr is a novel I enjoyed from start to finish. Written in the era of the polite avant-garde social activism exemplified by Bloomsbury, Lewis' most well-known novel is none of those things. It could logically be argued that Tarr is mean-spirited, but I prefer to think of it as a Nietzschean parody.4.4/5(14)Format: KindleAuthor: Wyndham LewisPeople also askWhat did Lewis say about Tarr?What did Lewis say about Tarr?Tarr, generally thought to be modelled on Lewis himself, displays disdain for the 'bourgeois-bohemians' around him, and vows to 'throw off humour' which he regards—especially in its English form—as a 'means of evading reality' unsuited to ambition and the modern world.Tarr - Wikipedia Jul 25, 2020 · His novels include his pre-World War I-era novel Tarr (set in Paris), and The Human Age, a trilogy comprising The Childermass (1928), Monstre Gai and Malign Fiesta (both 1955), set in the afterworld. -

Dora Marsden "The Stirner of Feminism" ?

Library.Anarhija.Net Dora Marsden ”The Stirner of Feminism” ? Did Dora Marsden ”transcend” Stirner? Bernd A. Laska Bernd A. Laska Dora Marsden ”The Stirner of Feminism” ? Did Dora Marsden ”transcend” Stirner? 2001 http://www.lsr-projekt.de/poly/enmarsden.html lib.anarhija.net 2001 The New Freewoman, 1 vol., 15th Jun 1913 to Dec 1913 (Reprint 1967); The Egoist, 6 vols., Jan 1914 to Dec 1919 (Reprint 1967). On Dora Marsden: Sidney E. Parker: The New Freewoman. Dora Marsden & Ben- Contents jamin R. Tucker. In: Benjamin R. Tucker and the Champions of Lib- erty, ed. by Michael E. Coughlin, Charles H. Hamilton, Mark A. Sul- Abstract ............................ 3 livan. New York 1986. pp.149-157; Life summary ......................... 3 Sidney E. Parker: Archists, Anarchists and Egoists. In: The Egoist ”The Max Stirner of Feminism” ? .............. 6 (London), Nr.8 (1986), pp.1-6. From anarchism to archism ................. 8 Both articles also available at: ”The Egoist Archive” sowie ”The Bibliography: ......................... 10 Memory Hole” Les Garner: A Brave and Beautiful Spirit. Dora Marsden 1882- 1960. Aldershot, Hants., GB 1990. 214pp. Bruce Clarke: Dora Marsden and Early Modernism. Gender, In- dividualism, Science. Ann Arbor, MI, USA 1996. 273pp. 2 11 of his wishes. Some anarchists were indeed for the idea of the ego as Abstract a sovereign ruler, but only when it had first changed itself in a def- inite way, whereas Marsden, as an archist, meant the real, existing, Dora Marsden (1882-1960) was the editor of some avant-garde unchanged individuals and their egos, their spontaneous wishes literary journals (1911-1919; Ezra Pound, T.S. -

Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and the Publication Of

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 11 (2000) : 63-72 Writing Dialogues, Reading Myths: Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and the Publication of Kora in Hell João Paulo Nunes Between 1909 and 1920, William Carlos Williams published in many literary magazines and managed to produce three books of poems despite his busy professional life as a doctor. However, the publication of the book Kora in Hell in 1920 marked a turning point in Williams’ career, as the volume, a collection of poetic prose fragments dedicated to Williams’ wife, Florence Herman, inaugurated a new creative period for the poet. The texts gathered in Kora in Hell resemble the prose poems written by the French symbolists, and reflect diverse genres and influences that expand the boundaries of traditional conceptions of the literary text. The history of Kora in Hell’s writing and publication shows the influence of literary dialogues exchanged with Ezra Pound, and of writers such as Arthur Rimbaud, Pietro Metastasio, E.W. Sutton Pickhardt, and Homer, in whose “Hymn to Demeter” lies the explanation of the myth of Kora, a disturbing evocation of spring and fertility. In October 1917, the American literary magazine The Little Review, edited by Margaret Anderson, published three prose fragments by Williams, under the title “Improvisations” (IV. 7: 19). By this time, Williams was no stranger to the literary world. Before the publication of the Improvisations in The Little Review, he had already published the book Poems in 1909 at his own expense, The Tempers in 1913, and Al Que Quiere! in 1917, and participated actively in poetry readings and theatre performances in Rutherford (New Jersey), his hometown, where he lived and practised medicine. -

Short Form American Poetry

SHORT FORM AMERICAN POETRY The Modernist Tradition Will Montgomery Chapter 1 Ezra Pound, H.D. and Imagism While Imagism is typically given foundational status in the modernist line of anglophone poetry, it was produced by a grouping as confected and irregular as any in the long history of twentieth-century avant- gardes. Ezra Pound, obviously, is central to this conversation, but in this chapter I will also pay close attention to H.D., whose poetry was the most rigorous exemplar of imagist practice (even if Pound remained for many poets of the modernist line the pre-eminent model). I discuss austerity, clarity and directness in this writing, and the complex relation- ship that Imagism has with figures of the inexpressible, both in its highly mediated adaptations of poetry of the French symbolist tradition and in the literature of ancient Greece, China and Japan. The relationship between the empirical and short form is usually taken as implicit by poets of the imagist and post-imagist line: a reduced style becomes an inevitable concomitant of this mode of writing. Yet the use of ellipsis and the handling of the linebreak in this poetry go a long way beyond the eschewal of ornamentation. There is a contradiction between the reduced style and the empirical ambitions of such poets – the desire for direct statement as a means of forging a relationship between object and artwork that is unmediated by the artifice of poetic language. The compression and ellipsis that characterises such writing, even at the level of the sentence, works against conventional sense- making, preventing the poetry from representing the things of the world with anything approaching directness.