Do Tax Havens Flourish?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tax Haven Networks and the Role of the Big 4 Accountancy Firms

-RXUQDORI:RUOG%XVLQHVV[[[ [[[[ [[[²[[[ Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of World Business journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jwb Tax haven networks and the role of the Big 4 accountancy firms Chris Jonesa,⁎, Yama Temouria,c, Alex Cobhamb a Economics & Strategy Group, Aston Business School, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK b Tax Justice Network, Oxford, UK c Faculty of Business, University of Wollongong Dubai, UAE ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This paper investigates the association between the Big 4 accountancy firms and the extent to which multi- Tax havens national enterprises build, manage and maintain their networks of tax haven subsidiaries. We extend inter- Varieties of capitalism nalisation theory and derive a number of hypotheses that are tested using count models on firm-level data. Our Corporate taxation key findings demonstrate that there is a strong correlation and causal link between the size of an MNE’s tax Poisson regression haven network and their use of the Big 4. We therefore argue that public policy related to the role of auditors can Big 4 accountancy firms have a significant impact on the tax avoidance behaviour of MNEs. 1. Introduction 2014 which has provided a number of clear insights. These documents showed that PwC assisted MNEs to obtain at least 548 legal but secret Given the impact that the recent financial crisis of 2008 has had on tax rulings in Luxembourg from 2002 to 2010. The rulings allowed the public finances of developed economies, the use of tax avoidance MNEs to channel hundreds of billions of dollars through Luxembourg, measures by multinational enterprises (MNEs) has come under in- arising from economic activities that took place in other jurisdictions creasing scrutiny from various governments and civil society organi- and with effective tax rates so low that they saved billions of dollars in sations across the world. -

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting

Tax Heavens: Methods and Tactics for Corporate Profit Shifting By Mark Holtzblatt, Eva K. Jermakowicz and Barry J. Epstein MARK HOLTZBLATT, Ph.D., CPA, is an Associate Professor of Accounting at Cleveland State University in the Monte Ahuja College of Business, teaching In- ternational Accounting and Taxation at the graduate and undergraduate levels. axes paid to governments are among the most significant costs incurred by businesses and individuals. Tax planning evaluates various tax strategies in Torder to determine how to conduct business (and personal transactions) in ways that will reduce or eliminate taxes paid to various governments, with the objective, in the case of multinational corporations, of minimizing the aggregate of taxes paid worldwide. Well-managed entities appropriately attempt to minimize the taxes they pay while making sure they are in full compliance with applicable tax laws. This process—the legitimate lessening of income tax expense—is often EVA K. JERMAKOWICZ, Ph.D., CPA, is a referred to as tax avoidance, thus distinguishing it from tax evasion, which is illegal. Professor of Accounting and Chair of the Although to some listeners’ ears the term tax avoidance may sound pejorative, Accounting Department at Tennessee the practice is fully consistent with the valid, even paramount, goal of financial State University. management, which is to maximize returns to businesses’ ownership interests. Indeed, to do otherwise would represent nonfeasance in office by corporate managers and board members. Multinational corporations make several important decisions in which taxation is a very important factor, such as where to locate a foreign operation, what legal form the operations should assume and how the operations are to be financed. -

The Relationship Between MNE Tax Haven Use and FDI Into Developing Economies Characterized by Capital Flight

1 The relationship between MNE tax haven use and FDI into developing economies characterized by capital flight By Ali Ahmed, Chris Jones and Yama Temouri* The use of tax havens by multinationals is a pervasive activity in international business. However, we know little about the complementary relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the developing world. Drawing on internalization theory, we develop a conceptual framework that explores this relationship and allows us to contribute to the literature on the determinants of tax haven use by developed-country multinationals. Using a large, firm-level data set, we test the model and find a strong positive association between tax haven use and FDI into countries characterized by low economic development and extreme levels of capital flight. This paper contributes to the literature by adding an important dimension to our understanding of the motives for which MNEs invest in tax havens and has important policy implications at both the domestic and the international level. Keywords: capital flight, economic development, institutions, tax havens, wealth extraction 1. Introduction Multinational enterprises (MNEs) from the developed world own different types of subsidiaries in increasingly complex networks across the globe. Some of the foreign host locations are characterized by light-touch regulation and secrecy, as well as low tax rates on financial capital. These so-called tax havens have received widespread media attention in recent years. In this paper, we explore the relationship between tax haven use and foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing countries, which are often characterized by weak institutions, market imperfections and a propensity for significant capital flight. -

Narrative Report on Panama

NARRATIVE REPORT ON PANAMA PART 1: NARRATIVE REPORT Rank: 15 of 133 Panama ranks 15th in the 2020 Financial Secrecy Index, with a high secrecy score of 72 but a small global scale weighting (0.22 per cent). How Secretive? 72 Coming within the top twenty ranking, Panama remains a jurisdiction of particular concern. Overview and background Moderately secretive 0 to 25 Long the recipient of drugs money from Latin America and with ample other sources of dirty money from the US and elsewhere, Panama is one of the oldest and best-known tax havens in the Americas. In recent years it has adopted a hard-line position as a jurisdiction that refuses to 25 to 50 cooperate with international transparency initiatives. In April 2016, in the biggest leak ever, 11.5 million documents from the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca revealed the extent of Panama’s involvement in the secrecy business. The Panama Papers showed the 50 to 75 world what a few observers had long been saying: that the secrecy available in Panama makes it one of the world’s top money-laundering locations.1 Exceptionally 75 to 100 In The Sink, a book about tax havens, a US customs official is quoted as secretive saying: “The country is filled with dishonest lawyers, dishonest bankers, dishonest company formation agents and dishonest How big? 0.22% companies registered there by those dishonest lawyers so that they can deposit dirty money into their dishonest banks. The Free Trade Zone is the black hole through which Panama has become one of the filthiest money laundering sinks in the huge world.”2 Panama has over 350,000 secretive International Business Companies (IBCs) registered: the third largest number in the world after Hong Kong3 and the British Virgin Islands (BVI).4 Alongside incorporation of large IBCs, Panama is active in forming tax-evading foundations and trusts, insurance, and boat and shipping registration. -

The Theory of International Tax Competition and Coordination

CHAPTER 5 The Theory of International Tax Competition and Coordination Michael Keen* and Kai A. Konrad†,‡ *International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Affairs Department,Washington DC 20431, USA †Max Planck Institute for Tax Law and Public Finance, Marstallplatz 1, 80539 Munich, Germany ‡Social Science Research Center Berlin, Germany Contents 1. Introduction 258 2. Uncoordinated Actions 262 2.1. Workhorse Models 263 2.1.1. The Zodrow, Mieszkowski, and Wilson (ZMW) Model 263 2.1.2. The Kanbur-Keen (KK) Model 275 2.2. Sequential Decision Making 278 2.3. Pure Profits and International Portfolio Diversification 282 2.4. Tax Competition with Multiple Instruments 284 2.5. Vertical Externalities and the Strategic Role of Internal Governance Structure 285 3. Coordination 288 3.1. Asymmetries and the Limits of Harmonization 289 3.2. Minimum Tax Rates 289 3.3. Coordination Among a Subset of Countries 293 3.4. Coordination Across a Subset of Instruments 295 3.5. Dynamic Aspects 296 3.5.1. Infinitely Repeated Interaction 296 3.5.2. Endogenous Savings and Time Consistent Taxation 298 3.5.3. Stock Effects and Agglomeration 302 4. Broadening the Perspective 303 4.1. Bidding for Firms 303 4.2. Preferential Regimes 305 4.3. Information Exchange and Implementation of the Residence Principle 308 4.4. Tax Havens 311 4.4.1. Which Countries Become Tax Havens? 311 4.4.2. Are Tax Havens Good or Bad? 312 4.4.3. Closing Down Tax Havens 314 4.5. Formula Apportionment 315 4.6. Political Economy and Agency Issues 318 4.6.1. Tax Competition and Leviathan 318 4.6.2. -

Gray Areas of Offshore Financial Centers

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2008 Gray Areas of Offshore Financial Centers Matthew Benjamin Davis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Davis, Matthew Benjamin, "Gray Areas of Offshore Financial Centers" (2008). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1167 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gray Areas of Offshore Financial Centers Matthew Davis Chancellor's Honors Program Senior Project Introduction Offshore finance often brings to mind illegal activities such as money laundering and tax evasion. Over the years, these shady dealings have become associated with offshore banking due to its lax regulations and strict adherence to client secrecy. On the other hand, offshore financial centers can also be used for legitimate reasons such as setting up offshore hedge funds. Many motives drive the move of funds offshore and increase the activity of offshore financial centers. Some are completely legal, while others focus more on criminal activity. Often, the line between these legal and illegal activities is a very thin one. Specific regulations cannot be made to cover every single new situation, and taxpayers are forced to make decisions about how to interpret the law. -

From the Double Irish to the Bermuda Triangle by Joseph P

(C) Tax Analysts 2014. All rights reserved. does not claim copyright in any public domain or third party content. From the Double Irish to the Bermuda Triangle by Joseph P. Brothers In brief, the Irish Finance Department’s decision to Joseph P. Brothers is an toughen Ireland’s idiosyncratic corporate residency de- associate with Caplin & termination rules is unlikely to significantly impede the Drysdale in Washington. basic mechanics of the strategy or to allay the EU’s The ‘‘double Irish’’ tax concerns. The double Irish structure depends most cru- planning strategy em- cially on the U.S. check-the-box entity classification ployed by Apple and other rules to create a hybrid entity mismatch arrangement, multinational companies as well as the cost-sharing provisions of Treas. reg. sec- has been in the main- tion 1.482-7. stream press of late, as At its most basic level, the point of the structure is has the challenge brought simply to shift income from an Irish operating subsidi- by the European Union. This article explains ary into a holding company located in a zero-tax juris- how the strategy works, the gist of the EU diction, while also avoiding inclusions to the U.S. par- position, and the reaction of the Irish govern- ent that might result from outbound intellectual ment. property transfers. From the U.S. perspective, the oper- ating subsidiary is disregarded under the check-the-box regime so that the cash flowing into the holding com- ecently, the EU’s antitrust and competition regu- pany does not trigger subpart F inclusions to the U.S. -

The State Administration of International Tax Avoidance

THE STATE ADMINISTRATION OF INTERNATIONAL TAX AVOIDANCE Omri Marian* Forthcoming, Harvard Business Law Review, 2016 Abstract This Article documents a process in which a national tax administration in one jurisdiction, is consciously and systematically assisting taxpayers to avoid taxes in other jurisdictions. The aiding tax administration collects a small amount tax from the aided taxpayers. Such tax is functionally structured as a fee paid for government-provided tax avoidance services. Such behavior can be easily copied (and probably is copied) by other tax administrations. The implications are profound. On the normative front, the findings should fundamentally change our understanding of the concept of international tax competition. Tax competition is generally understood to be the adoption of low tax rates in order to attract investments into the jurisdiction. Instead, this Article identifies an intentional “beggar thy neighbor” behavior, aimed at attracting revenue generated by successful investments in other jurisdictions, without attracting actual investments. The result is a distorted competitive environment, in which revenue is denied from jurisdictions the infrastructure and workforce of which support economically productive activity. On the practical front, the findings suggest that internationally coordinated efforts to combat tax avoidance are misaimed. Current efforts are largely aimed at curtailing aggressive taxpayer behavior. Instead, the Article proposes that the focus of such efforts should be curtailing certain rogue practices adopted by national tax administrations. To explain these arguments, the Article uses an original dataset. In November of 2014, hundreds of advance tax agreement (ATAs) issued by Luxembourg’s Administration des Contributions Directes (Luxembourg’s Inland Revenue, or LACD) to multinational corporate taxpayers (MNCs) were made public. -

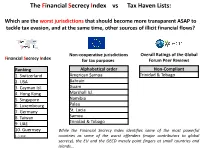

The Financial Secrecy Index Vs Tax Haven Lists

The Financial Secrecy Index vs Tax Haven Lists: Which are the worst jurisdictions that should become more transparent ASAP to tackle tax evasion, and at the same time, other sources of illicit financial flows? Non-cooperative jurisdictions Overall Ratings of the Global Financial Secrecy Index for tax purposes Forum Peer Reviews Ranking Alphabetical order Non-Compliant 1. Switzerland American Samoa Trinidad & Tobago 2. USA Bahrain 3. Cayman Isl. Guam 4. Hong Kong Marshall Isl. 5. Singapore Namibia 6. Luxembourg Palau 7. Germany St. Lucia 8. Taiwan Samoa 9. UAE Trinidad & Tobago 10. Guernsey While the Financial Secrecy Index identifies some of the most powerful (…) 112. countries as some of the worst offenders (major contributors to global secrecy), the EU and the OECD merely point fingers at small countries and islands… Financial Secrecy Non-cooperative Overall Index jurisdictions Ratings Number of jurisidctions considered not 1 (NC) & 7 112* 9 transparent / cooperative enough? (PC)** Average Secrecy Score of the worst 69.61 74.37*** 65.25 jurisdictions? [Top 10 jurisdictions only] [NC only] [0 = Transparency; 100 = Full Secrecy] Offshore Financial Services (FSI’s Global 58% [Top 10 jurisdictions only] 0.15%*** 0.0001% Scale Weight) of the worst jurisdictions? [NC only] [100% = all market share of offshore financial services] FSI Share (% of financial secrecy for which 32% [Top 10 jurisdictions only] 2.94%*** 0.09% the worst jurisdictions are responsable) [NC only] [100% = responsible for all of the world’s financial secrecy] * None of the 112 jurisdiction reaches at least 60% of transparency (no jurisdiction has a Secrecy Score equal to or below 40%). -

The Double Irish and Dutch Sandwich Tax Strategies: Could a General Anti- Avoidance Rule Counteract the Problems Caused by Utilisation of These Structures?

DANIELLE THORNE THE DOUBLE IRISH AND DUTCH SANDWICH TAX STRATEGIES: COULD A GENERAL ANTI- AVOIDANCE RULE COUNTERACT THE PROBLEMS CAUSED BY UTILISATION OF THESE STRUCTURES? LLM RESEARCH PAPER LAWS 516: TAXATION, DOMESTIC AND INTERNATIONAL FACULTY OF LAW 2013 Danielle Thorne Laws 516 Abstract This paper analyses the Double Irish and Dutch Sandwich tax structures used by large multinational enterprises. These structures enable companies to shift significant profits to offshore tax havens through the use of wholly owned subsidiaries in Ireland and the Netherlands. Application of the New Zealand General Anti- Avoidance rule in s BG 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007 reveals that any attempt to counteract these structures would be highly fact dependent. The paper concludes that it would be possible to apply the rule, but that there would be practical difficulties in relation to enforceability of the Commissioner’s ruling. A similar result was reached when applying the United States General Anti-Avoidance rule. The attempted application of the General Anti-Avoidance rules reveals a fundamental flaw in the income tax system. That is, the inability of the current system to regulate and control intangible resources and technology based transactions. Word length The text of this paper (excluding abstract, table of contents, footnotes and bibliography) comprises approximately 14,994 words. Subjects and Topics General Anti-Avoidance Rule Income Tax Act 2007 Multinational Enterprises Double Irish and Dutch Sandwich Tax Avoidance 2 Danielle Thorne Laws 516 Contents I Introduction .................................................................................... 5 II Avoidance Strategies: The Double Irish and the Dutch Sandwich.... 6 A Residency or Source Based Taxation .............................................. 7 B The Double Irish: Company Structure and Licensing Arrangements 8 C The Double Irish: Tax Benefits .................................................... -

Knocking on Tax Haven's Door: Multinational Firms and Transfer Pricing

KNOCKING ON TAX HAVEN’S DOOR: MULTINATIONAL FIRMS AND TRANSFER PRICING Ronald B. Davies, Julien Martin, Mathieu Parenti, and Farid Toubal* Abstract—This paper analyzes the transfer pricing of multinational firms. intrafirm, is generally not available. Moreover, it is impos- Intrafirm prices may systematically deviate from arm’s-length prices for two motives: pricing to market and tax avoidance. Using French firm-level sible to observe the counterfactual arm’s-length prices of an data on arm’s-length and intrafirm export prices, we find that the sensi- intrafirm transaction (see Diewert et al., 2006, for details). tivity of intrafirm prices to foreign taxes is reinforced once we control for Since the arm’s-length price is not observed, tax authorities pricing-to-market determinants. Most important, we find no evidence of tax avoidance if we disregard tax haven destinations. Tax avoidance through have to determine the market price, which raises obvious transfer pricing is economically sizable. The bulk of this loss is driven by definitional and methodological issues. the exports of 450 firms to ten tax havens. In this paper, we overcome both difficulties. We observe the export prices under each mode (arm’s length or intrafirm) I. Introduction at the level of firms, countries, and products. Moreover, our econometric methodology allows us to compare the intrafirm wealth of empirical evidence finds that within a multi- price used between a multinational and its affiliate with the Anational enterprise (MNE), reported profits vary sys- corresponding arm’s-length price charged by a firm shipping tematically with local corporate tax rates.1 This may be due to an unrelated party. -

Tax Cuts and Leprechauns by Paul Krugman June 15, 2018 – the New York Times

Tax cuts and Leprechauns By Paul Krugman June 15, 2018 – The New York Times The political news seems even more horrible So cutting the tax rate, according to this story, than usual today. So to get away from the will bring in lots of capital from abroad. This headlines a bit, I’m going to commit some will drive the rate of return down and wages economics. Specifically, I want to pull together up, so that in the long run the benefits of the some thoughts — some inspired by Gabriel tax cut will flow to workers rather than Zucman’s recent work, some of my own — shareholders. about the case or lack thereof for corporate tax Even if this story were right, long run effects cuts, the centerpiece of the only major aren’t the whole story for policy – in the long legislation enacted under Trump. run, we are all dead, and meanwhile capital Tax cuts: The rationale owners have a chance to take the money and run. So even if the eventual effect of the tax cut As Figure 1 shows, the immediate effect of were to raise wages, there might well be years, cutting the corporate tax rate has been, even decades, when a tax cut for corporations surprise, a big fall in taxes collected from is mainly a tax cut for wealthy shareholders. corporations. We’re looking at something on the order of $110 billion in revenue loss at an And as Figure 2 shows, so far there has been annual rate, which is real money – roughly the no visible effect on wages.