Hegemony and Media in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media Performance in Sri Lanka (Related to Selected Newspaper Media from April of 1983 to September of 1983)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 23, Issue 1, Ver. 8 (January. 2018) PP 25-33 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Ethnic Crisis and Newspaper Media performance in Sri Lanka (Related to selected Newspaper media from April of 1983 to September of 1983) Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Department of Political Science University of Kelaniya Kelaniya Corresponding Author: Assistant Lecturer Sarasi Chaya Bandara Abstract: The strong contribution denoted by media, in order to create various psychological printings to contemporary folk consciousness within a chaotic society which is consist of an ethnic conflict is extremely unique. Knowingly or unknowingly media has directly influenced on intensification of ethnic conflict which was the greatest calamity in the country inherited to a more than three decades history. At the end of 1970th decade, the newspaper became as the only media which is more familiar and which can heavily influence on public. The incident that the brutal murder of 13 military officers becoming victims of terrorists on 23rd of 1983 can be identified as a decisive turning point within the ethnic conflict among Sinhalese and Tamils. The local newspaper reporting on this case guided to an ethnical distance among Sinhalese and Tamils. It is expected from this investigation, to identify the newspaper reporting on the case of assassination of 13 military officers on 23rd of July 1983 and to investigate whether that the government and privet newspaper media installations manipulated their own media reporting accordingly to professional ethics and media principles. The data has investigative presented based on primary and secondary data under the case study method related with selected newspapers published on July of 1983, It will be surely proven that journalists did not acted to guide the folk consciousness as to grow ethnical cordiality and mutual trust. -

29 Complaints Against Newspapers

29 complaints against newspapers PCCS, Colombo, 07.06.2007 The Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka had received 29 complaints against newspapers during the first quarter of this year of which the commission had dealt with. A statement by the commission on its activities is as follows: The Press Complaints Commission of Sri Lanka (PCCSL) was established three and a half years ago (Oct. 2003) by the media to resolve disputes between the press, and the public speedily and cost-effectively, for both, the press and the public, outside the statutory Press Council and the regular courts system. We hope that the PCCSL has made things easier for editors and journalists to dispose of public complaints on matters published in your newspapers, and at no costs incurred in the retention of lawyers etc. In a bid to have more transparency in the work of the Dispute Resolution Council of the PCCSL, the Commission decided to publish the records of the complaints it has received. Complaints summary from January - April 2007 January PCCSL/001/01/2007: Thinakkural (daily) — File closed. PCCSL/OO2/O1/2007: Lakbima (daily)— Goes for mediation. PCCSL/003 Divaina (daily)- Resolved. PGCSL/004/01 /2007: Mawbima — Resolved. (“Right of reply” sent direct to newspaper by complainant). PCCSL/005/01/2007: Lakbima (Sunday) — Goes for mediation. February PCCSL/OO 1/02/2007: The Island (daily) — File closed. PCCSL/O02/02/2007: Divaina (daily) — File closed. F’CCSL/003/02/2007: Lakbima (daily) File closed. PCCSL/004/02/2007: Divaina (daily)— File closed. PCCSL/005/02/2007: Priya (Tamil weekly) — Not valid. -

Alison Phillips Editor, Daily Mirror Media Masters – September 26, 2018 Listen to the Podcast Online, Visit

Alison Phillips Editor, Daily Mirror Media Masters – September 26, 2018 Listen to the podcast online, visit www.mediamasters.fm Welcome to Media Masters, a series of one to one interviews with people at the top of the media game. Today, I’m here in Canary Wharf, London, and at the offices of the Daily Mirror, joined by their editor in chief, Alison Phillips. Previously in charge of the Sunday Mirror and Sunday People, she was also launch editor of New Day, the short-lived newspaper, in 2016. She also leads on addressing gender imbalance at Mirror publisher Reach, heading up their Women Together network, and is this year’s Society of Editor’s popular columnist of the year. Alison, thank you for joining me. Hi. Alison, you were appointed in March. It must have been an incredibly proud moment for you, how is it going? It’s going really well, I think. I hope. It’s been a busy few months, because obviously Reach has bought the Express as well, so there have been a lot of issues going on. But in terms of the actual paper at the Mirror, I hope, I feel, that we’re reaching a point of sustained confidence, which is so important for a paper. We’ve had some real success on campaigns, which I think is really our lifeblood. And I think we’re managing to energise the staff, which is absolutely essential for a well-functioning newspaper. Is it more managerial at the moment with the organisational challenges that you’ve been dealing with? Because you must, as the leader of the business, as the editor, you’ve got so many things you could be doing, you’ve got to choose, having to prioritise. -

Family Planning in Ceylon1

1 [This book chapter authored by Shelton Upatissa Kodikara, was transcribed by Dr. Sachi Sri Kantha, Tokyo, from the original text for digital preservation, on July 20, 2021.] FAMILY PLANNING IN CEYLON1 by S.U. Kodikara Chapter in: The Politics of Family Planning in the Third World, edited by T.E.Smith, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London, 1973, pp 291-334. Note by Sachi: I provide foot note 1, at the beginning, as it appears in the published form. The remaining foot notes 2 – 235 are transcribed at the end of the article. The dots and words in italics, that appear in the text are as in the original. No deletions are made during transcription. Three tables which accompany the article are scanned separately and provided. Table 1: Ceylon: population growth, 1871-1971. Table 2: National Family Planning Programme: number of clinics and clinic-population ratio by Superintendent of Health Service (SHS) Area, 1968-9. Table 3: Ceylon: births, deaths and natural increase per 1000 persons living, by ethnic group. The Table numbers in the scans, appear as they are published in the book; Table XII, Table XIII and Table XIV. These are NOT altered in the transcribed text. Foot Note 1: In this chapter the following abbreviations are used: FPA, Family 2 Planning Association, LSSP, Lanka Samasamaja Party, MOH, Medical Officer of Health, SLFP, Sri Lanka Freedom Party; SHS, Superintendent of Health Services; UNP, United National Party. Article Proper The population of Ceylon has grown rapidly over the last 100 years, increasing more than four-fold between 1871 and 1971. -

Clippings January 2020.Pdf

-1- mqj;am; - wreK Èkh - 2020-01-01 -2- mqj;am; - Èjhsk Èkh - 2020-01-01 -3- Newspaper – Daily Mirror Date – 01-01-2020 -4- mqj;am; - ,xld§m Èkh - 2020-01-01 -5- mqj;am; - wreK Èkh - 2020-01-01 -6- mqj;am; - /i Èkh - 2020-01-01 -7- Newspaper – Daily FT Date – 01-01-2020 -8- Newspaper – Daily FT Date – 01-01-2020 -9- Newspaper – Daily Mirror Date – 01-01-2020 -10- Newspaper – Daily News Date – 01-01-2020 -11- Newspaper – Ceylon Today Date – 02-01-2020 -12- Newspaper – Daily FT Date – 02-01-2020 -13- Newspaper – Daily News Date – 02-01-2020 -14- Newspaper – Daily Mirror Date – 02-01-2020 -15- Newspaper – Daily Mirror Date – 02-01-2020 -16- Newspaper – Ceylon Today Date – 03-01-2020 -17- mqj;am; - ÈkñK Èkh - 2020-01-03 -18- Newspaper – The Island Date – 03-01-2020 -19- mqj;am; - uõìu Èkh - 2020-01-03 -20- Newspaper – Daily Mirror Date – 04-01-2020 -21- Newspaper – Sunday Morning Date – 05-01-2020 -22- Newspaper – Sunday Times Date – 05-01-2020 -23- Newspaper – Sunday Observer Date – 05-01-2020 -24- Newspaper – Sunday Island Date – 05-01-2020 -25- Newspaper – Daily News Date – 06-01-2020 -26- mqj;am; - ÈkñK Èkh - 2020-01-07 -27- mqj;am; - wo Èkh - 2020-01-07 -28- mqj;am; - uõìu Èkh - 2020-01-07 -29- Newspaper – Daily FT Date – 07-01-2020 -30- mqj;am; - /i Èkh - 2020-01-08 -31- mqj;am; - ÈkñK Èkh - 2020-01-08 -32- Newspaper – Ceylon Today Date – 08-01-2020 -33- Newspaper – The Island Date – 08-01-2020 -34- Newspaper – Daily News Date – 09-01-2020 -35- Newspaper – Daily FT Date – 09-01-2020 -36- mqj;am; - uõìu Èkh - 2020-01-10 -37- Newspaper -

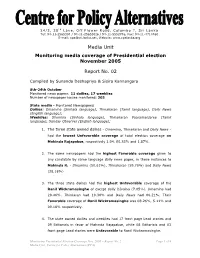

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

PDF995, Job 7

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara First week from nomination: 8th-15th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 94 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); • The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.14, 00% and 1.82%. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda Rajapakse. - Dinamina (43.56%), Thinakaran (56.21%) and Daily News (29.32%). • The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe, of any daily news paper. Dinamina had 28.82%. Thinkaran had 8.67% and Daily News had 12.64%. • Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe, was 10.75%, 5.10% and 11.13% respectively. • The state owned dailies and weeklies had 04 front page Lead stories and 02 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 02 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. State media coverage of two main candidates (in sq.cm% of total election coverage) Mahinda Rajapakshe Ranil W ickramasinghe Newspaper Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable Dinamina 43.56 1.14 10.75 28.88 Silumina 28.82 10.65 18.41 30.65 Daily news 29.22 1.82 11.13 12.64 Sunday Observer 23.24 00 12.88 00.81 Thinakaran 56.21 00 03.41 00.43 Thi. -

You Are What You Read

You are what you read? How newspaper readership is related to views BY BOBBY DUFFY AND LAURA ROWDEN MORI's Social Research Institute works closely with national government, local public services and the not-for-profit sector to understand what works in terms of service delivery, to provide robust evidence for policy makers, and to help politicians understand public priorities. Bobby Duffy is a Research Director and Laura Rowden is a Research Executive in MORI’s Social Research Institute. Contents Summary and conclusions 1 National priorities 5 Who reads what 18 Explaining why attitudes vary 22 Trust and influence 28 Summary and conclusions There is disagreement about the extent to which the media reflect or form opinions. Some believe that they set the agenda but do not tell people what to think about any particular issue, some (often the media themselves) suggest that their power has been overplayed and they mostly just reflect the concerns of the public or other interests, while others suggest they have enormous influence. It is this last view that has gained most support recently. It is argued that as we have become more isolated from each other the media plays a more important role in informing us. At the same time the distinction between reporting and comment has been blurred, and the scope for shaping opinions is therefore greater than ever. Some believe that newspapers have also become more proactive, picking up or even instigating campaigns on single issues of public concern, such as fuel duty or Clause 28. This study aims to shed some more light on newspaper influence, by examining how responses to a key question – what people see as the most important issues facing Britain – vary between readers of different newspapers. -

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation

Freedom of Expression in Sri Lanka: How the Sri Lankan Constitution Fuels Self-Censorship and Hinders Reconciliation By Clare Boronow Human Rights Study Project University of Virginia School of Law May 2012 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 II. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND SELF -CENSORSHIP .................................................................... 3 A. Types of self-censorship................................................................................................... 4 1. Good self-censorship .................................................................................................... 4 2. Bad self-censorship....................................................................................................... 5 B. Self-censorship in Sri Lanka ............................................................................................ 6 III. SRI LANKA ’S CONSTITUTION FACILITATES THE VIOLATION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION, THEREBY PROMOTING SELF -CENSORSHIP ............................................................................ 11 A. Express textual limitations on the freedom of expression.............................................. 11 B. The Constitution handcuffs the judiciary ....................................................................... 17 1. All law predating the 1978 Constitution is automatically valid ................................. 18 2. Parliament may enact unconstitutional -

Bringing the Buddha Closer: the Role of Venerating the Buddha in The

BRINGING THE BUDDHA CLOSER: THE ROLE OF VENERATING THE BUDDHA IN THE MODERNIZATION OF BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA by Soorakkulame Pemaratana BA, University of Peradeniya, 2001 MA, National University of Singapore, 2005 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2017 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Soorakkulame Pemaratana It was defended on March 24, 2017 and approved by Linda Penkower, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies Joseph Alter, PhD, Professor, Anthropology Donald Sutton, PhD, Professor Emeritus, Religious Studies Dissertation Advisor: Clark Chilson, PhD, Associate Professor, Religious Studies ii Copyright © by Soorakkulame Pemaratana 2017 iii BRINGING THE BUDDHA CLOSER: THE ROLE OF VENERATING THE BUDDHA IN THE MODERNIZATION OF BUDDHISM IN SRI LANKA Soorakkulame Pemaratana, PhD. University of Pittsburgh, 2017 The modernization of Buddhism in Sri Lanka since the late nineteenth century has been interpreted as imitating a Western model, particularly one similar to Protestant Christianity. This interpretation presents an incomplete narrative of Buddhist modernization because it ignores indigenous adaptive changes that served to modernize Buddhism. In particular, it marginalizes rituals and devotional practices as residuals of traditional Buddhism and fails to recognize the role of ritual practices in the modernization process. This dissertation attempts to enrich our understanding of modern and contemporary Buddhism in Sri Lanka by showing how the indigenous devotional ritual of venerating the Buddha known as Buddha-vandanā has been utilized by Buddhist groups in innovative ways to modernize their religion. -

HUM, He Assisted Olcott in the Collection of Funds For

P 0.-HISTORY OF EDUCATION 246. HUM, "Anagarika Dharmapala as an Educator."Journal of the National Education Societ ofCeylon.va.15, 1964. pp. 18 -32. When Dharmapala was a youth he came underthe influence of Colonel Olcott and FadameBlavatsky of the Theosophical Society who visited Ceylon in the188018. He assisted Olcott in the collection of funds forthe Buddhist educational movement.He later developed to be a great educational and socialreformer, and a religious leader.He worked in the fields of educational and social reform in both India and Ceylon.He was an admirer of the educational systems of Japan and the United States, and he urged India and Ceylon toestablish an educationalsystem that would make every child grow up to be an intelligentthinking individual with a consciousness active for the good of all beings. He set up schools to translate intopractice the idealshe had in mind.He emphasised the importance of technical education, especiallyinthe fields of agriculture and industry.He started several industrial schools and tried to wean students away from too bookish an education. He was a great believer in adult education, which he thought could be best promoted throughthe mass media. For this purpose, he started a Sinhala newspaper in Ceylon and anEnglish journal The lishabodhi Jou.1. which had a wide circulationin'IndlTW" o. Ceylon. 247. KARUNARATNE, V. T. G. "Educational changes in Ceylon." ---Ceylon Daily Nears. December 3, 1963. 1550 words. December 1, 1960 is significant in the history of education in Ceylon as the day on which one of the fetters of colonialism, namely the denominationalschool system, was shattered.The Britishencouraged missionary enterprise in Ceylon and were reluctant to enter the field of education. -

SRI LANKA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

SRI LANKA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service 4 July 2011 SRI LANKA 4 JULY 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN SRI LANKA FROM 2 TO 27 JUNE 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON SRI LANKA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 2 TO 27 JUNE 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ..................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Key political events (1948 to December 2010) ............................................... 3.01 The internal conflict (1984 to May 2009) ......................................................... 3.15 Government treatment of (suspected) members of the LTTE ........................ 3.28 The conflict's impact: casualties and displaced persons ................................ 3.43 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Key recent developments (January – May 2011) ........................................... 4.01 Situation