Northen Biscayne Bay in 1776 : Tequesta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Florida Historical Quarterly

Florida Historical Quarterly V OLUME XXXVIII July 1959 - April 1960 Published by the FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXXVIII Anderson, Russell H., The Shaker Community in Florida, 29 Arnade, Charles W., Florida On Trial, review of, 254 Bashful, Emmett W., The Florida Supreme Court, review of, 355 Beater, Jack, True Tales of the Florida West Coast, review of, 175 Book reviews, 74, 172, 252, 347 Boyd, Mark F., Historic Sites in and Around the Jim Woodruff Reservoir Area, Florida-Georgia, review of, 351 Camp, Vaughan, Jr., book review of, 173 Capron, Louis, The Spanish Dance, 91 Carpetbag Rule in Florida, review of, 357 Carson, Ruby Leach, book review of, 252 Carter, Clarence Edwin, (ed.), The Territory of Florida, review of, 347 Contributors, 90, 194, 263, 362 Corliss, Carlton J., Henry M. Flagler, Railroad Builder, 195 Covington, James W., Trade Relations Between Southwestern Florida and Cuba, 1600-1840, 114; book reviews of, 175, 254 Cushman, Joseph D., Jr., The Episcopal Church in Florida Dur- ing the Civil War, 294 Documents Pertaining to the Georgia-Florida Frontier, 1791- 1793, by Richard K. Murdoch, 319 Doherty, Herbert J., book review by, 78; The Whigs of Florida, 1845-1854, review of, 173 Douglas, Marjory Stoneman, Hurricane, review of, 178 Dovell, J. E., book review of, 351 Dodd, Dorothy, book review of, 347 “Early Birds” of Florida, by Walter P. Fuller, 63 Episcopal Church in Florida During the Civil War, by Joseph D. Cushman, Jr., 294 Florida - A Way of Life, review of, 252 Florida Handbook, review of, 172 Florida on Trial, 1593-1602, review of, 254 Florida Supreme Court, review of, 355 Foreman, M. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

The Everglades Before Reclamation

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 26 Number 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 26, Article 4 Issue 1 1947 The Everglades Before Reclamation J. E. Dovell Part of the American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Article is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Dovell, J. E. (1947) "The Everglades Before Reclamation," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 26 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol26/iss1/4 Dovell: The Everglades Before Reclamation THE EVERGLADES BEFORE RECLAMATION by J. E. DOVELL Within our own generation a scientist who always weighed his words could say of the Everglades: Of the few as yet but very imperfectly explored regions in the United States, the largest perhaps is the southernmost part of Florida below the 26th degree of northern latitude. This is particularly true of the central and western portions of this region, which inland are an unmapped wilderness of everglades and cypress swamps, and off-shore a maze of low mangrove “keys” or islands, mostly unnamed and uncharted, with channels, “rivers” and “bays” about them which are known only to a few of the trappers and hunters who have lived a greater part of their life in that region. 1 This was Ales Hrdlicka of the Smithsonian Institution, the author of a definitive study of anthropology in Florida written about 1920 ; and it is not far from the truth today. -

SUMMER ADVENTURES Indigenous Origins O N T H E R O a D EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK

SUMMER ADVENTURES Indigenous Origins O N T H E R O A D EVERGLADES NATIONAL PARK DID YOU KNOW? The Indigenous peoples of the Americas arrived from Asia more than 10,000 years ago. The prevailing theory is that they crossed from Siberia to what is now Alaska. Over the ensuing millennia, many of them migrated east and south, populating areas as distant as present-day Nevada and Brazil. Some of them formed communities in the Everglades. One of the major Indigenous peoples in the Everglades were the Calusa, who lived along the southwestern coast of the Florida Peninsula. They used shells to build earthwork platforms and barriers, potentially as protection from the ocean, and they subsisted largely on fish they caught from dugout canoes they crafted. The Calusa, together with the Tequesta and other Indigenous peoples, numbered about 20,000 when the Spanish landed in Florida in the early 16th century. By the late 18th century, their populations were dramatically smaller, decimated by diseases introduced by the Spanish to which they had no immunity. Around that time, Creeks from Georgia and northern Florida began migrating to South Florida, where they assumed the name “Seminoles.” In addition to hunting and fishing, the Seminole farmed corn, squash, melons, and other produce. Beginning in 1818, the U.S. waged a series of wars to remove the Seminoles from Florida. It managed to forcibly relocate some Seminoles to the Indian Territory, though others evaded capture by venturing into the Everglades. Today, Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee tribes include thousands of members. Some live on reservations, while others live in off-reservation towns or cities. -

Cuban Experiences: 1959-1969 in Miami Pathfinder August, 2015

Cuban Experiences: 1959-1969 in Miami Pathfinder August, 2015 1. Key Books and Search Terms Search Terms Search su:Cuban American in the Library Catalog. The search will retrieve titles with subject headings containing “Cuban American” or Cuban Americans Specific subject searches: su:Cuban Americans History su:Cuban Florida su:Cuban Americans Biography Books Bretos, Miguel A. Cuba & Florida: Exploration of an Historic Connection, 1539-1991. Miami, Fla: Historical Association of Southern Florida (1991). Casavantes Bradford, Anita. The Revolution is for the Children: The Politics of Childhood in Havana and Miami, 1959-1962. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press (2014). García, María Cristina. Havana USA: Cuban Exiles and Cuban Americans in South Florida, 1959-1994. Berkeley: University of California Press (1996). Rieff, David. The Exile: Cuba in the Heart of Miami. New York: Simon & Schuster (1993). Shell-Weiss, Melanie. Coming to Miami: A Social History. Gainesville: University Press of Florida (2009). 2. Journal and Newspaper Articles Search the following databases, listed alphabetically in A-to-Z Databases, for articles: Academic Search Premier Access World News Latin America & the Caribbean (Gale World Scholar) Miami Herald New York Times (1851-2010) New York Times (1980-Current) ProQuest Central Search The Voice/La Voz newspapers of the Archdiocese of Miami (1961-1990). Available at St. Thomas University Library Media Archive, http://library.stu.edu/ulma/va/3005/. 3. Pertinent Historical Articles Badillo, David A. "Cuban Catholics in the United States, 1960-1980: Exile and Integration." The Americas 67, no. 1 (07, 2010): 118-119. Mandri, Flora M. González. "Operation Pedro Pan: A Tale of Trauma and Remembrance." Latino Studies 6, no. -

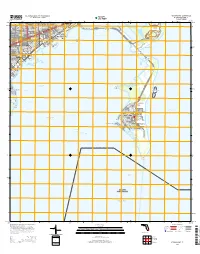

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Key Biscayne, Florida

S W W KEY BISCAYNE QUADRANGLE U.S.2 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 7 T SW 31ST RD H H U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLORIDA-MIAMI-DADE CO. A V E 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 1ST TER SW 14THAVE 80°15' SW 2 972 12'30" 913 10' 80°07'30" 2ND ST ¬ «¬ SW576 2000mE 577 578 « 579 40 580 581 582 583 584 585 16 586 940 000 FEET 587 25°45' n█ 25°45' SW 22ND TER SW 29TH AVE E SW 23RD ST SW 21ST AVE V 9 S A «¬ W D 28 000m SW 34TH AVE SW 23RD TER R William M 48 N SW 23RD ST SW 25TH AVE 3 VE Lamar 2 SW 1ST AVE West Bay Heights 10 I A BRICKELL AVE Powell 28 SW 24TH ST 2 W SW 23RD AVE S M N IA Bridge Lake 48 D D SW 24TH TER M Bridge The S A SHORE DR W DR RIC Y V B TS KENBACKER CSW A H Pines E G 40 Bay Bridge SW 24TH TER Y EI SW 25TH ST H SW 25TH ST S n█ W W SHORE DR E 10 SW 25TH TER 1 16 7 SW 26TH ST n█ ¤£1 T 17 Virginia Key 15 H SW 26TH ST n█ 16 A SW 26TH LN V E 16SW 27TH ST E Intracoastal Waterway M MICANOPY AVE n█ A T T54S R41E H L MIAMI D TEQUESTA LN A R H LAMB J R S ARTHUR n█ OVERBROOK ST T 14 28 R n█ 47 E D Sister n█ OR 28 10 SH F Banks 47 AY A B I WASHINGTON ST S R Deering I S L Channel E E R SWANSON AVE S D T Grove R TRAPP AVE IC H K C E A LINCOLN AVE Isle N E n█ B B MATILDA ST A 510 000 Ocean View C INIA S K VIRG Virginia Beach W W E E20 SHIPPING AVE Heights AV R VIRGINIA ST 2 IL 22 C FEET MARY ST A 7 T S SW 32ND AVE W T R Y H H E Bear IG A T Bear V Cut E Cut Bridge 28 F 46 ¥^ OAK AVE 2846 n█ Dinner GRAND AVE GRAND AVE ▄PO 21 ¥^¥^ n Key 21 n█ █ Northwest Point CHARLES AVE FRANKLIN AVE Coconut 21 ROYAL RD Grove n█ n█ Dinner D V 28 L Key B 45 n█ 10 Channel 2845 N N P IN O O C D I N A A N R A A C VE 28 28 28 29 2844 MATHESON AVE 2844 Four-Way . -

Delaware in the American Revolution (2002)

Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Delaware in the American Revolution An Exhibition from the Library and Museum Collections of The Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House Washington, D. C. October 12, 2002 - May 3, 2003 HIS catalogue has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition, Delaware in the American Revolution , on display from October 12, 2002, to May 3, 2003, at Anderson House, THeadquarters, Library and Museum of the Society of the Cincinnati, 2118 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, D. C. 20008. It is the sixth in a series of exhibitions focusing on the contributions to the American Revolution made by the original 13 he season loudly calls for the greatest efforts of every states and the French alliance. Tfriend to his Country. Generous support for this exhibition was provided by the — George Washington, Wilmington, to Caesar Rodney, Delaware State Society of the Cincinnati. August 31, 1777, calling for the assistance of the Delaware militia in rebuffing the British advance to Philadelphia. Collections of the Historical Society of Delaware Also available: Massachusetts in the American Revolution: “Let It Begin Here” (1997) New York in the American Revolution (1998) New Jersey in the American Revolution (1999) Rhode Island in the American Revolution (2000) Connecticut in the American Revolution (2001) Text by Ellen McCallister Clark and Emily L. Schulz. Front cover: Domenick D’Andrea. “The Delaware Regiment at the Battle of Long Island, August 27, 1776.” [detail] Courtesy of the National Guard Bureau. See page 11. ©2002 by The Society of the Cincinnati. -

CHAINING the HUDSON the Fight for the River in the American Revolution

CHAINING THE HUDSON The fight for the river in the American Revolution COLN DI Chaining the Hudson Relic of the Great Chain, 1863. Look back into History & you 11 find the Newe improvers in the art of War has allways had the advantage of their Enemys. —Captain Daniel Joy to the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety, January 16, 1776 Preserve the Materials necessary to a particular and clear History of the American Revolution. They will yield uncommon Entertainment to the inquisitive and curious, and at the same time afford the most useful! and important Lessons not only to our own posterity, but to all succeeding Generations. Governor John Hancock to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, September 28, 1781. Chaining the Hudson The Fight for the River in the American Revolution LINCOLN DIAMANT Fordham University Press New York Copyright © 2004 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored ii retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotation: printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson : the fight for the river in the American Revolution / Lincoln Diamant.—Fordham University Press ed. p. cm. Originally published: New York : Carol Pub. Group, 1994. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8232-2339-6 (pbk.) 1. New York (State)—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 2. United States—History—Revolution, 1775-1783—Campaigns. 3. Hudson River Valley (N.Y. -

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc. 7407 La Jolla Boulevard www.raremaps.com (858) 551-8500 La Jolla, CA 92037 [email protected] A Chorographical Map, of the Northern Department of North-America Drawn from the Latest and most accurate Observations Stock#: 56067 Map Maker: Romans Date: 1780 Place: Amsterdam Color: Hand Colored Condition: VG+ Size: Price: SOLD Description: Finely engraved map of xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx during the American Revolution. Originally engraved by Bernard Romans in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1778, the map is one of the rarest maps of the American Revolutionary War period. This edition of the map was issued by the Amsterdam firm of Covens & Mortier, based closely on one published by Bernard Romans in New Haven, Connecticut in 1778. Bernard Romans Bernard Romans was born in Delft, Netherlands about 1720. He learned mapmaking and surveying in England, before moving to the Colonies in 1757. He served as a Surveyor in Georgia, where he would rise to become Deputy Surveyor General in 1766 and one of the most important Colonial mapmakers. He is perhaps best known for his extensive survey and mapping or the Coastal Waters of East Florida. William Gerard De Braham, the Surveyor General for the Southern Colonies appointed him Deputy Surveyor General for the Southern District in 1773 and wrote A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida, published in 1775, one of the most important works on Florida. When war broke out in 1775, Romans was in Boston where Paul Revere was engraving Romans' maps of Florida. Romans enlisted in the American cause and was appointed a Captain and served with Benedict Arnold and Nathaniel Greene in their attacks on Fort George and Fort Ticonderoga. -

Guidebook: American Revolution

Guidebook: American Revolution UPPER HUDSON Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site http://nysparks.state.ny.us/sites/info.asp?siteId=3 5181 Route 67 Hoosick Falls, NY 12090 Hours: May-Labor Day, daily 10 AM-7 PM Labor Day-Veterans Day weekends only, 10 AM-7 PM Memorial Day- Columbus Day, 1-4 p.m on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday Phone: (518) 279-1155 (Special Collections of Bailey/Howe Library at Uni Historical Description: Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site is the location of a Revolutionary War battle between the British forces of Colonel Friedrich Baum and Lieutenant Colonel Henrick von Breymann—800 Brunswickers, Canadians, Tories, British regulars, and Native Americans--against American militiamen from Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire under Brigadier General John Stark (1,500 men) and Colonel Seth Warner (330 men). This battle was fought on August 16, 1777, in a British effort to capture American storehouses in Bennington to restock their depleting provisions. Baum had entrenched his men at the bridge across the Walloomsac River, Dragoon Redoubt, and Tory Fort, which Stark successfully attacked. Colonel Warner's Vermont militia arrived in time to assist Stark's reconstituted force in repelling Breymann's relief column of some 600 men. The British forces had underestimated the strength of their enemy and failed to get the supplies they had sought, weakening General John Burgoyne's army at Saratoga. Baum and over 200 men died and 700 men surrendered. The Americans lost 30 killed and forty wounded The Site: Hessian Hill offers picturesque views and interpretative signs about the battle. Directions: Take Route 7 east to Route 22, then take Route 22 north to Route 67. -

Defense of West Point on the Hudson, 1775 – 1783

GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology Defense of West Point on the Hudson, 1775 – 1783 The Hudson River and West Point GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology PURPOSE To inform students how possession of the Hudson River Valley and fortifications at West Point were vital to defense of the American Colonies during the Revolutionary War. The Hudson River and West Point GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology OUTLINE • Background/Orientation • Brief Chronology of Events • Military Implications • Major Fortifications • Summary • Conclusion The Hudson River and West Point GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology References • Walker, Paul. Engineers of Independence: A documentary of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775-1783. Washington, DC: Historical Division, Office of Administrative Services, Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1981. • Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson. New York: Carol, 1989. • LTC Dave Palmer. The River and The Rock: A History of Fortress West Point, 1775-1783. New York: Greenwood, 1969. • U.S. Military Academy Department of History. "West Point Fortifications Staff Ride Notecards." http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/pdfs/ Second Edition (1998). The Hudson River and West Point GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology Background/Orientation 1 of 3 • Located in the Hudson Highlands, 50mi North of New York City. • 16000 acres of Orange County, NY. • Located along the Hudson River’s “S” Curve The Hudson River and West Point GE 301 Introduction to Military Geology Background/Orientation 2 of 3 The Hudson River -

Download Catalogue

Dreams 1 of Unknown Islands Sasha Wortzel Sound installation, Cover: polymer PLA filament Big Cypress—Partnership 9.5 x 9.5 x 18 in. with Nature 2 3 7 min Year unknown Photo courtesy of Film still Pedro Wazzan Courtesy of the Everglades National Park Archives Kristan Kennedy Let us begin with “seashell resonance,” the folk more things, and therefore it’s been harder for me myth or phenomenon claiming that when you place to articulate specificity. I am thinking about different a conch shell against your ear, you can hear the binaries around gender and around time—around ocean. In actuality, the undulating and rushing sounds people, plants, and animals being labeled as invasive are generated by ambient noise passing through versus native—about queer ecology and queer the shell’s spiral body into our spiral ears, creating communities and histories.”4 We spent some time The Museum an occlusion effect. It is, in this moment, that the talking about Hito Steyerl’s writings and her use of imagined sounds of waves and the very real blood the term “free fall,” where the artist/author describes of All Possible flowing through our curving veins start to sing the mixed-up-ness one feels in times of disorientation 1 to each other. We feel connected, transported— or when there is a lack of an orienting horizon in the transmuted! We are the ocean.2 distance. Steyerl expands on the potential space of Shells In their solo exhibition Dreams of Unknown unknowing when she writes, “Traditional modes Islands, Sasha Wortzel proposes similar plangency of seeing and feeling are shattered.