Italian-Hungarian Support for the Internal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6Th CICA-STR Conference

[Blank page] [blank page] Page • 2 Terrorism and Aggression: Towards Increased Freedom and Security Page • 3 [blank page] Page • 4 Terrorism and Aggression: Towards Increased Freedom and Security 6th Annual CICA-STR International Conference Program and Abstracts Burgas, Bulgaria 8 September through 11 September 2012 Edited by Tali K. Walters, J. Martín Ramírez, Tatyana Dronzina, & Lyndsey Harris Copyright © 2012 Tali K. Walters, J. Martín Ramírez, Tatyana Dronzina, & Lyndsey Harris Printed in Bulgaria All rights reserved ISBN: 978-954-91557-7-8 Page • 6 CONTENTS • GREETINGS • CONFERENCE ORGANIZERS • LOCAL EXECUTIVE PLANNING COMMITTEE • INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • EXECUTIVE PLANNING COMMITTEE • SPONSORS • SCIENTIFIC PROGRAM • ABSTRACTS • LIST OF PARTICIPANTS • PREVIOUS PUBLICATIONS • PARTICIPANTS’ INDEX • NOTES Page • 7 [Blank Page] Page • 8 GREETINGS Dear friends, As conference organizers, we are pleased to welcome you to Bulgaria for the 6th Annual CICA- STR International Conference on Terrorism and Aggression: Towards Increased Freedom and Security. An impressive group of scholars, researchers and analysts have gathered here to discuss one of the most challenging issues facing contemporary societies in Bulgaria and around the world. More specifically, about 80 active participants are attending this CICA-STR Conference, either physically or sending their scientific contributions. They come from a total of 23 countries from all the continents: twelve from the European Union (Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Rumania, Spain, United Kingdom and, obviously, our host Bulgaria) and other Eastern European countries (Macedonia, Moldova, Russia, Turkey); six from Asia: Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan), Indostan (India, Pakistan), Hong Kong - China and Iran; two Africans (Nigeria, South Africa), and one from Oceania (New Zealand), as well as delegates from the two American countries that hosted our last two international conferences (USA and Colombia). -

Turkey's Relations with Italy (1932-39)

TURKEY’S RELATIONS WITH ITALY (1932-39): REALITIES AND PERCEPTIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY MEHMET DOĞAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS JULY 2020 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Oktay Fırat Tanrısever Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Ebru Boyar Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Bağcı (METU, IR) Prof. Dr. Ebru Boyar (METU, IR) Assist. Prof. Dr. Onur İşçi (Bilkent Uni., IR) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Mehmet Doğar Signature : iii ABSTRACT TURKEY’S RELATIONS WITH ITALY (1932-39): REALITIES AND PERCEPTIONS Doğar, Mehmet M.Sc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ebru Boyar July 2020, 233 pages This thesis examines Turkey’s relations with Italy between 1932 and 1939 through key historical events and analyses the role of Italy in Turkish foreign policy making. -

Topography, Cartography and Cadastre in Bulgaria at the End of 19Th Century and in the Beginning of 20Th Century – First Steps and First Results

Topography, Cartography and Cadastre in Bulgaria at the End of 19th Century and in the Beginning of 20th Century – First Steps and First results Veneta KOTSEVA, Bulgaria Keywords: Topography, Cartography, History of Geodesy SUMMARY The topographical and cartographical activities performed on the Bulgarian territories during the 1877-1878 Russian-Turkish war and in thereafter are described. There was a Topographic Corps formed during the War with the Russian Army preparing for military actions on the Bulgarian lands with a task to improve the found triangulation network of European Turkey and to modernize the Russian ”General Map”. After passing the Danube River, however, it was established that there was no developed triangulation and that the “General Map”, issued in 1829, was aged. Geodesy and cartography in our country developed in two main directions after the Liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman Rule in 1878: for the needs of the Army and for economic purposes. Up to year 1932 the State Geographic Institute to the Ministry of War was the only in the country institution for the performance of the main geodetic measurement works. Special attention is devoted to the first printed editions for topography, military geodesy and cartography in Bulgaria in the period 1891-1920. First applications of cartographical and geodetic products for the purposes of the statistics in the Principality Bulgaria in 1897 are presented. The history and the development of the geodetic and cartographic activities in Bulgaria are in fact history of the military topography and cartography of Bulgaria. The scientific and the scientific applied contributions of the Geographic Institute to the Ministry of War and of the Bulgarian geodesists who worked in it and who left a bright trail in various spheres of military topography, higher geodesy, geodetic astronomy, cartography, photogrammetry, gravimetry and the other geosciences are incontestable, big and of great significance. -

Rifatre Book

The Rise and Fall of Trenches A Contribution to the Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Beginning of World War I This page was intentionally left blank. i The Rise and Fall of Trenches A Contribution to the Commemoration of the 100th Anniversary of the Beginning of World War I Coordinator Project Reference 555485-CITIZ-1-2014-1-EL-CITIZ-REMEM This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. ii This page was intentionally left blank. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Participating Organisations .................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ...............................................................................................................................vi In Lieu of a Preface ...............................................................................................................................1 Photos ...................................................................................................................................................3 Articles ..................................................................................................................................................5 Lyceum Artis – Sofia, Bulgaria ................................................................................................................................................................6 -

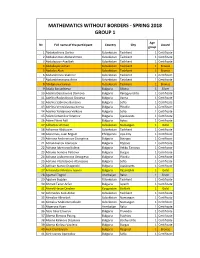

Mathematics Without Borders - Spring 2018 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2018 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdukadirova Darina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdukarimov Abdurahmon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 3 Abdulazizov Asadbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 4 Abdullayev Adnan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 5 Abdulov Alan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 6 Abdurahimov Shahrier Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdurakhmanova Aziza Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 8 Abidjanova Sureya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 9 Adalia Barutchieva Bulgaria Silistra 1 Silver 10 Adelina Desislavova Dankova Bulgaria Panagyurishte 1 Certificate 11 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 12 Adelina Sabinova Borisova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 13 Adelina Ventsislavova Koeva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 14 Adelina Yordanova Velkova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 15 Adem Dzhemilov Ademov Bulgaria Lyaskovets 1 Certificate 16 Adem Fikret Adil Bulgaria Aytos 1 Certificate 17 Adhamov Ahmad Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Gold 18 Adkamov Abduazim Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 19 Adoremos, Juan Miguel Philippines Lipa City 1 Certificate 20 Adreana Andreanova Georgieva Bulgaria Bourgas 1 Certificate 21 Adrian Ivanov Atanasov Bulgaria Popovo 1 Certificate 22 Adriana Iskrenova Koleva Bulgaria Veliko Tarnovo 1 Certificate 23 Adriana Ivanova Petkova Bulgaria Burgas 1 Certificate 24 Adriana Lyubomirova Georgieva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 25 Adriana Vladislavova Atanasova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 26 Adriyan Ivanov Draganski Bulgaria -

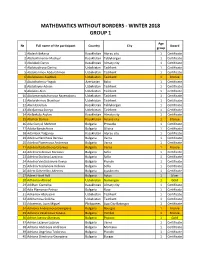

Mathematics Without Borders - Winter 2018 Group 1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - WINTER 2018 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abdesh Bekarys Kazakhstan Atyrau city 1 Certificate 2 Abdrakhmanov Madiyar Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 1 Certificate 3 Abdubek Daryn Kazakhstan Almaty city 1 Certificate 4 Abdukadirova Darina Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 5 Abdukarimov Abdurahmon Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 6 Abdulazizov Asadbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 7 Abdulhalimov Yagub Azerbaijan Baku 1 Certificate 8 Abdullayev Adnan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdulov Alan Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 10 Abdumannobzhonova Rayenabonu Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdurahimov Shaxriyor Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 12 Aben Ersultan Kazakhstan Taldykorgan 1 Certificate 13 Abidjanova Sureya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 14 Abilbekuly Asylan Kazakhstan Almaty city 1 Certificate 15 Abylkali Daniya Kazakhstan Astana city 1 Bronze 16 Ada Gunyul Mehmet Bulgaria Provadia 1 Certificate 17 Adalia Barutchieva Bulgaria Silistra 1 Certificate 18 Adambek Tolganay Kazakhstan Atyrau city 1 Certificate 19 Adelina Nencheva Berova Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 20 Adelina Plamenova Andreeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Certificate 21 Adelina Radostinova Grozeva Bulgaria Varna 1 Bronze 22 Adelina Sabinova Borisova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 23 Adelina Stoilova Lazarova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 24 Adelina Ventsislavova Koeva Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Certificate 25 Adelina Yordanova Velkova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 26 Adem Dzhemilov Ademov Bulgaria Lyaskovets 1 Certificate -

Proceeding of Selected Abstracts at KIN2021 in Pdf File Format

KIN2021 е финансирана от Фонд “Научни изследвания” по процедурата за подкрепа на международни научни форуми, провеждани в България по Договор КП-06-МНФ/24 от 16.12.2020 CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL HERITAGE Preservation, Presentation, Digitalization Proceedings selected abstracts, 2021 Veliko Tarnovo, Bulgaria Institute of Mathematics and Informatics, BAS The proceedings is funded by the National Research Fund of Bulgaria for 2021 under a program to support international scientific forums held in Bulgaria with a contract № KP-06-MNF/24 from 16.12.2020 This work is subject to copyright. Permission to make digital or hard copies of portions of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee, provided that the copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that the copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To otherwise reproduce or transmit in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage retrieval system or in any other way requires written permission from the publisher. 2021 http://www.math.bas.bg/vt/isc-kin/ Editors: Prof. PhD Petko St. Petkov Assoc. Prof. PhD Galina Bogdanova Copy editors: Assist. Prof. PhD Nikolay Noev Assist. Prof. PhD Kalina Sotirova-Valkova Kaloyan Nikolov © Editors, authors of papers, 2021 Institute of Mathematics and Informatics at the BAS, Bulgaria PREFACE The Seventh Scientific Conference with International Participation "Cultural and Historical Heritage: Preservation, Presentation, Digitization" (CHH2021) will be held in a hybrid form (present and virtual) from 21 to 24 April 2021. The main directions of the conference are the preservation, digitalization and presentation of the cultural and historical heritage (CHH). -

Winter21-Group1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS ‐ WINTER 2021 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abboskhudjaev Alisherkhuja Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 2 Abdimanap Aisultan Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 3 Abdrahman Yusufi AFGHANISTAN KABUL 1 Certificate 4 Abdukadirov Abdukadir Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 5 Abdukadirov Tamir Uzbekiston Tashkent 1 Certificate 6 Abdukadirova Sahiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 7 Abdulmuhtarov Zhavohir Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Silver 8 Abdulwaheb Alim AFGHANISTAN KABUL 1 Certificate 9 Abdumalikov Abdukhalil Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 10 Abduvahobov Alisher Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Bronze 11 Abdyrahman Ibragim Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 12 Abidov Salihbek Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 13 Abilseit Yerasyl Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 14 Abriol, Willen Philippines City of Naga 1 Certificate 15 Abzalova Jamila Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 16 Adel Dzhyuneyt Topchu Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Gold 17 Adelia Miglenova Davidova Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Certificate 18 Adelina Dobreva Peneva Bulgaria Burgas 1 Silver 19 Adelina Hristomirova Mutafchieva Bulgaria Ruse 1 Certificate 20 Adelina Iskrenova Zhekova Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Bronze 21 Adelina Milenova Nikolova Bulgaria Bozhurishte 1 Certificate 22 Adelina Rumanetsova Bulgaria Varna 1 Silver 23 Adelina Velianova Dobreva Bulgaria Burgas 1 Certificate 24 Adile Nurdzhan Halil Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 25 Adilov Umar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Silver 26 Adrian Aleksandrov Ivanov Bulgaria Sofia 1 Silver 27 Adrian Alexandrov Vassilev Bulgaria -

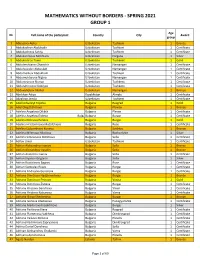

Spring21-Group1

MATHEMATICS WITHOUT BORDERS - SPRING 2021 GROUP 1 Age № Full name of the participant Country City Award group 1 Abbasova Aisha Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Bronze 2 Abdukadirov Abdukadir Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 3 Abdukadirova Sahiya Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 4 Abdukarimova Mokhlaroi Uzbekistan Fergana 1 Silver 5 Abdukodirov Tamir Uzbekiston Toshkent 1 Gold 6 Abdulmuhtarov Zhavohir Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 7 Abdulvosidov Abbosbek Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 8 Abdumalikov Abdukhalil Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 9 Abdumuhtarova Nigina Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Certificate 10 Abdunosirova Nuriya Uzbekiston Toshkent 1 Certificate 11 Abdurahmonov Kobiljon Uzbekiston Toshkent 1 Certificate 12 Abduvahobov Alisher Uzbekistan Namangan 1 Bronze 13 Abirkhan Adiya Kazakhstan Almaty 1 Certificate 14 Abzalova Jamila Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 15 Adel Dzhuneyt Topchu Bulgaria Razgrad 1 Gold 16 Adel Oleg Dzhorova Bulgaria Plovdiv 1 Bronze 17 Adelina Angelova Diklich Bulgaria Pleven 1 Certificate 18 Adelina AngelovaToteva BulgariaBulgaria Burgas Burgas NBU "Mihail1 Certificate Lakatnik" 19 Adelina Dobreva Peneva Bulgaria Burgas 1 Gold 20 Adelina Hristomirova Mutafchieva Bulgaria Ruse 1 Certificate 21 Adelina Ljubomirova Kuneva Bulgaria Svishtov 1 Bronze 22 Adelina Milenova Nikolova Bulgaria Bozhurishte 1 Silver 23 Adelina Simeonova Dimitrova Bulgaria Sofia 1 Certificate 24 Adilov Umar Uzbekistan Tashkent 1 Certificate 25 Adrian Aleksandrov Ivanov Bulgaria Sofia 1 Bronze 26 Adrian Alexandrov Vassilev Bulgaria Sofia 1 Bronze