Native and Naturalized Conifers of Nevada a Checklist and Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

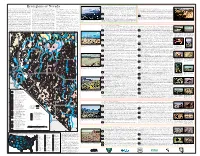

Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 Is a Mountainous, Deeply Dissected, and Westerly Tilting Fault Block

5 . S i e r r a N e v a d a Ecoregions of Nevada Ecoregion 5 is a mountainous, deeply dissected, and westerly tilting fault block. It is largely composed of granitic rocks that are lithologically distinct from the sedimentary rocks of the Klamath Mountains (78) and the volcanic rocks of the Cascades (4). A Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, Vegas, Reno, and Carson City areas. Most of the state is internally drained and lies Literature Cited: high fault scarp divides the Sierra Nevada (5) from the Northern Basin and Range (80) and Central Basin and Range (13) to the 2 2 . A r i z o n a / N e w M e x i c o P l a t e a u east. Near this eastern fault scarp, the Sierra Nevada (5) reaches its highest elevations. Here, moraines, cirques, and small lakes and quantity of environmental resources. They are designed to serve as a spatial within the Great Basin; rivers in the southeast are part of the Colorado River system Bailey, R.G., Avers, P.E., King, T., and McNab, W.H., eds., 1994, Ecoregions and subregions of the Ecoregion 22 is a high dissected plateau underlain by horizontal beds of limestone, sandstone, and shale, cut by canyons, and United States (map): Washington, D.C., USFS, scale 1:7,500,000. are especially common and are products of Pleistocene alpine glaciation. Large areas are above timberline, including Mt. Whitney framework for the research, assessment, management, and monitoring of ecosystems and those in the northeast drain to the Snake River. -

HISTORY of the TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST a Compilation

HISTORY OF THE TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST A Compilation Posting the Toiyabe National Forest Boundary, 1924 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Chronology ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Bridgeport and Carson Ranger District Centennial .................................................................... 126 Forest Histories ........................................................................................................................... 127 Toiyabe National Reserve: March 1, 1907 to Present ............................................................ 127 Toquima National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ....................................................... 128 Monitor National Forest: April 15, 1907 – July 2, 1908 ........................................................ 128 Vegas National Forest: December 12, 1907 – July 2, 1908 .................................................... 128 Mount Charleston Forest Reserve: November 5, 1906 – July 2, 1908 ................................... 128 Moapa National Forest: July 2, 1908 – 1915 .......................................................................... 128 Nevada National Forest: February 10, 1909 – August 9, 1957 .............................................. 128 Ruby Mountain Forest Reserve: March 3, 1908 – June 19, 1916 .......................................... -

Committee for the Review and Oversight of the TRPA and the Marlette Lake Water System

STATE OF NEVADA Department of Conservation & Natural Resources Steve Sisolak, Governor Bradley Crowell, Director Charles Donohue, Administrator MEMORANDUM DATE: December 11, 2019 TO: Committee for the Review and Oversight of the TRPA and the Marlette Lake Water System THROUGH: Charles Donohue, Administrator FROM: Meredith Gosejohan, Tahoe Program Manger SUBJECT: California spotted owls in Nevada The following information on the California spotted owl in Nevada is in response to questions from the Committee during the meeting held on November 19, 2019. Currently, there is only one known nesting pair of spotted owls in the State of Nevada. The pair were discovered in Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park in 2015 and have occupied the same territory every year since. The territory is monitored annually by the Nevada Tahoe Resource Team’s (NTRT) biologist from the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW). The pair has successfully fledged one juvenile from the nest in three different years: 2015, 2017, and 2018. There have also been five documented incidental spotted owl sightings in other parts of the Carson Range since 2015. These spotted owls are a subspecies called the California spotted owl (Strix occidentalis occidentalis). There are two other subspecies in the western United States (Northern and Mexican), both of which are federally listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The California spotted owl was recently petitioned for federal listing as well, but the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) announced in November 2019, that listing was not warranted at this time. (Click here to read the decisions summary) Spotted owls are native to the Tahoe Basin, though they have been relatively rare on the Nevada side and are typically observed on the California side or other parts of the Sierra Nevada. -

Stuart, Trees & Shrubs

Excerpted from ©2001 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. May not be copied or reused without express written permission of the publisher. click here to BUY THIS BOOK INTRODUCTION HOW THE BOOK IS ORGANIZED Conifers and broadleaved trees and shrubs are treated separately in this book. Each group has its own set of keys to genera and species, as well as plant descriptions. Plant descriptions are or- ganized alphabetically by genus and then by species. In a few cases, we have included separate subspecies or varieties. Gen- era in which we include more than one species have short generic descriptions and species keys. Detailed species descrip- tions follow the generic descriptions. A species description in- cludes growth habit, distinctive characteristics, habitat, range (including a map), and remarks. Most species descriptions have an illustration showing leaves and either cones, flowers, or fruits. Illustrations were drawn from fresh specimens with the intent of showing diagnostic characteristics. Plant rarity is based on rankings derived from the California Native Plant Society and federal and state lists (Skinner and Pavlik 1994). Two lists are presented in the appendixes. The first is a list of species grouped by distinctive morphological features. The second is a checklist of trees and shrubs indexed alphabetically by family, genus, species, and common name. CLASSIFICATION To classify is a natural human trait. It is our nature to place ob- jects into similar groups and to place those groups into a hier- 1 TABLE 1 CLASSIFICATION HIERARCHY OF A CONIFER AND A BROADLEAVED TREE Taxonomic rank Conifer Broadleaved tree Kingdom Plantae Plantae Division Pinophyta Magnoliophyta Class Pinopsida Magnoliopsida Order Pinales Sapindales Family Pinaceae Aceraceae Genus Abies Acer Species epithet magnifica glabrum Variety shastensis torreyi Common name Shasta red fir mountain maple archy. -

Pines in the Arboretum

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MtJ ARBORETUM REVIEW No. 32-198 PETER C. MOE Pines in the Arboretum Pines are probably the best known of the conifers native to The genus Pinus is divided into hard and soft pines based on the northern hemisphere. They occur naturally from the up the hardness of wood, fundamental leaf anatomy, and other lands in the tropics to the limits of tree growth near the Arctic characteristics. The soft or white pines usually have needles in Circle and are widely grown throughout the world for timber clusters of five with one vascular bundle visible in cross sec and as ornamentals. In Minnesota we are limited by our cli tions. Most hard pines have needles in clusters of two or three mate to the more cold hardy species. This review will be with two vascular bundles visible in cross sections. For the limited to these hardy species, their cultivars, and a few hy discussion here, however, this natural division will be ignored brids that are being evaluated at the Arboretum. and an alphabetical listing of species will be used. Where neces Pines are readily distinguished from other common conifers sary for clarity, reference will be made to the proper groups by their needle-like leaves borne in clusters of two to five, of particular species. spirally arranged on the stem. Spruce (Picea) and fir (Abies), Of the more than 90 species of pine, the following 31 are or for example, bear single leaves spirally arranged. Larch (Larix) have been grown at the Arboretum. It should be noted that and true cedar (Cedrus) bear their leaves in a dense cluster of many of the following comments and recommendations are indefinite number, whereas juniper (Juniperus) and arborvitae based primarily on observations made at the University of (Thuja) and their related genera usually bear scalelikie or nee Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, and plant performance dlelike leaves that are opposite or borne in groups of three. -

Field Trip Summary Report for Sierra Nevadas, California: Chico NE, SE

\ FIElD TRIP SUMMARY FOR SIERRA NEVADAS, CALIFORNIA CHICO NE, SE AND SACRAMENTO NE I. INTRODUCTION Field reconnaissance of the work area is an integral part for the accurate interpretation of aerial photography. Photographic signatures are compared to the actual wetland's appearance in the field by observing vegetation, soil and topo~raphy. This information is weighted with seasonality and conditIOns at both dates of photography and ground truthing. The project study area was located in northern California's Sierra Nevada Mountains. Ground truthing covered the area of each 1:100,000: Chico NE, Chico SE, and Sacramento NE. This field summary describes the data we were able to collect on the various wetland sites and the plant communities observed. II. FIELD MEMBERS Barbara Schuster Martel Laboratories, Inc. Dennis Peters U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service III. FIELD DATES July 27 - August 2, 1988 IV. AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY Type: Color Infrared Transparencies Scale: 1:58,000 V. COLLATERAL DATA U.S. Geological Survey Quadrangles Soil Survey of HI Dorado Area. California, 1974. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey of Nevada County Area. California, 1975. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. 1 Soil Survey of Sierra Valley Area. California. Parts of Sierra. Plumas. and Lassen Counties, 1975. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey - Tahoe Basin Area. California and Nevada, 1974. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service and Forest Service. Soil Survey - Amador Area. California, 1965. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. -

Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan O the Sky Highway T

Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan Highway to the Sky CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE & VISION PURPOSE & VISION 1 PLAN PURPOSE 2 CORRIDOR SETTING 3 VISION & GOALS 6 STAKEHOLDER & PUBLIC OUTREACH 7 CHAPTER 2: MOUNT ROSE SCENIC BYWAY’S INTRINSIC VALUES INTRINSIC VALUES 19 TERRAIN 20 OWNERSHIP 22 LAND USE & COMMUNITY RESOURCES 24 VISUAL QUALITY 26 CULTURAL RESOURCES 30 RECREATIONAL RESOURCES 34 HYDROLOGY 40 VEGETATION COMMUNITIES & WILDLIFE 42 FUEL MANAGEMENT & FIRES 44 CHAPTER 3: THE HIGHWAY AS A TRANSPORTATION FACILITY TRANSPORTATION FACILITIES 47 EXISTING ROADWAY CONFIGURATION 48 EXISTING TRAFFIC VOLUMES & TRENDS 49 EXISTING TRANSIT SERVICES 50 EXISTING BICYCLE & PEDESTRIAN FACILITIES 50 EXISTING TRAFFIC SAFETY 50 EXISTING PARKING AREAS 55 PLANNED ROADWAY IMPROVEMENTS 55 CHAPTER 4: ENHANCING THE BYWAY FOR VISITING, LIVING & DRIVING CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES & ACTION ITEMS 57 PRESERVE THE SCENIC QUALITY & NATURAL RESOURCES 59 BALANCE RECREATION ACCESS WITH TRANSPORTATION 68 & SAFETY NEEDS CONNECT PEOPLE WITH THE CORRIDOR 86 PROMOTE TOURISM 94 CHAPTER 5: CORRIDOR STEWARDSHIP CORRIDOR STEWARDSHIP 99 MANAGING PARTNERS 100 CURRENT RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DOCUMENTS 102 | i This Plan was funded by an On Our Way grant from the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency and a Federal Scenic Byway Grant from the Nevada Department of Transportation. ii | Mount Rose Scenic Byway Corridor Management Plan CHAPTER ONE 1 PURPOSE & VISION Chapter One | 1 The Corridor PLAN PURPOSE The Mount Rose Scenic Byway is officially named the “Highway to the Management Sky” and offers travelers an exciting ascent over the Sierra Nevada from Plan identifies the sage-covered slopes of the eastern Sierra west to Lake Tahoe. Not only goals, objectives does the highway connect travelers to a variety of recreation destinations and cultural and natural resources along the Byway, it also serves as a and potential minor arterial connecting both tourists and commuters from Reno to Lake enhancements to Tahoe. -

Douglas- Fir Limber Pine Lodgepole Pine Ponderosa Pine Blue Spruce

NAME ORIGIN BARK FEMALE CONES NEEDLES WHERE USES TRIVIA Named by Smooth gray bark To 4ÂÂ long, Soft, flat, 2-sided, Found on north or Railroad crossties, State tree of Scottish botanist on young trees yellowish to light 1¼″ long and south-facing slopes, mine timbers, for Oregon. David Douglas. with numerous brown hanging cones rounded at the tip. in shady ravines and building ships and The Latin name DOUGLAS- Fir is from the resin scars. with uniquely 3- Dark yellow green or on rocky slopes boats, construction psuedotsuga Middle English pointed bracts blue green. Shortly where the soil is lumber, plywood, means FIR firre and Old protruding from cone stalked spreading fairly deep. telephone poles, ÂÂfalse Psuedotsuga English fyrh. scales like a snakes- mostly in two rows. fencing, railroad-car fir.ÂÂ menziesii tongue. Single small groove construction, boxes Can drop 2 on topside of needles and crates, flooring, million seeds in and single white line furniture, ladders a good year. on underside of and pulpwood. needles. Pine is from the Light gray to Big (to 9ÂÂ long) Stout in clusters of 5 Found on rocky, Lumber, railroad Cones start to LIMBER Latin pinus and blackish brown. cylindrical, greenish needles, to 3″ long. gravelly slopes, cross ties, poles, appear after the the Old English Smooth and silvery brown, with thick, Straight or slightly ridges and peaks. turpentine, tar and tree reaches 20 PINE pin. gray on young broad scales. Cone curved, not sticky to fuel. years of age. Pinus flexilis trees. scales lack prickles. the touch. Dark green. Pine is from the Bark is grayish or Light yellow brown, Stout, twisted Found in well Lumber, knotty Many Plains Latin pinus and light brown, thin reddish or dark green, needles, mostly in drained soils, dry pine paneling, Indian tribes the Old English and with many lopsided cones to pairs, to 2½″ long. -

Section 1: Introduction

Carson Range Fuel Reduction and Wildfire Prevention Strategy Section 1: Introduction Purpose of this Plan This comprehensive fuels reduction and wildfire prevention plan is a unified, multi-jurisdictional strategic synopsis of the planning efforts of local, county, state, tribal, and federal entities. The proposed projects in this plan provide a 10-year strategy to reduce the risk of large and destructive wildfire in the Carson Range planning area. The plan’s outcome is to 1) propose projects that create “community defensible space”, 2) comprehensively display all proposed fuel reduction treatments, and 3) facilitate communication and cooperation among those responsible for plan implementation. If implemented, this plan will provide greater protection to the people, infrastructure, and resources in the planning area. This plan was developed to comply with the White Pine County Conservation, Recreation, and Development Act of 2006 (Public Law 109-432 [H.R.6111]), which amended the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act of 1998 (Public Law 105-263) to include the following language: “development and implementation of comprehensive, cost-effective, multi- jurisdictional hazardous fuels reduction and wildfire prevention plans (including sustainable biomass and biofuels energy development and production activities) for the Lake Tahoe Basin (to be developed in conjunction with the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency), the Carson Range in Douglas and Washoe Counties and Carson City in the State, and the Spring Mountains in the State, that are-- (I) subject to approval by the Secretary; and (II) not more than 10 years in duration” This comprehensive plan is supported by 15 partners who each have a role in wildland fuels or fire management in the planning area (see “Agencies Involved” below). -

Species Interactions and Abiotic Effects on Stand Structure of Bristlecone Pine (Pinus Longaeva) and Limber Pine (Pinus Flexilis)

Species interactions and abiotic effects on stand structure of bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis) Selene Arellano1, Anna Douglas2, Neira Ibrahimovic3 , Janette Jin1 1University of California, Berkeley; 2University of California, Santa Cruz; 3University of California, Los Angeles ABSTRACT Plants experience a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses based on their environmental conditions. Demographic stages—recruits, saplings, and adults—may react differently under stress. In this study, we examine how the factors of aspect, substrate, and competition affect the stand structure of Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus longaeva) and limber pine (Pinus flexilis), which are among the few trees that can withstand the stressful subalpine environment. We surveyed an even distribution of north and south- facing slopes with both dolomite and granite substrate in the White Mountains of Inyo National Forest, California. We recorded the density of different demographic stages of both tree species and tested how neighboring trees affected the cone production of bristlecones. We found that the effect of aspect and substrate depended on the demographic stage. We also found no evidence of competition between bristlecone and limber. Taken together, our results suggest that abiotic factors are more important than biotic factors in determining bristlecone and limber establishment. Overall, we suggest that abiotic factors are more influential in shaping subalpine plant communities. Keywords: bristlecone pine, limber pine, competition, abiotic stress, stand structure INTRODUCTION and have low levels of phosphorus, which is an essential element for plant development Plants may experience extreme stress (Wright and Mooney 1965, Malhotra et al. when they are growing in environments with 2018). -

Quaternary Research 79 (2013) 309

Quaternary Research 79 (2013) 309 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yqres Corrigendum Corrigendum to “Late-Holocene response of limber pine (Pinus flexilis) forests to fire disturbance in the Pine Forest Range, Nevada, USA” [Quaternary Research 78 (2012) 465–473] Robert K. Shriver a,1, Thomas A. Minckley a,b,⁎ a Dept. of Botany, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA b Roy J. Shlemon Center for Quaternary Studies, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071, USA The purpose of Shriver and Minckley (2012) “Late-Holocene re- The occurrence of such a large population of whitebark pine in this sponse of limber pine (Pinus flexilis) forests to fire disturbance in portion of northwestern Nevada is notable in itself. The Pine Forest the Pine Forest Range, Nevada, USA” was to assess historic responses Range is not particularly high in comparison to surrounding ranges to disturbance (fire) using pollen percentage data derived from a that do not have similar forest types. The presence of a few but exceed- sediment core using superimposed epoch analysis. This work was ingly rare limber pines suggests that there might have been historic conducted in a small glacial tarn, Blue Lake, located in an isolated processes that have favored one species versus the other over time — mountain range of northwestern Nevada, the Pine Forest Range. maybe even fire. The differences in the ecology of the two species are The benefit of this site was the unique setting of an isolated forest significant enough to suspect that they would have different climatic that added to our knowledge of disturbance in five-needle pine eco- and disturbance responses. -

Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines

Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines Conservation Genetics of High Elevation Five-Needle White Pines Andrew D. Bower, USDA Forest Service, Olympic National Forest, Olympia, WA; Sierra C. McLane, University of British Columbia, Dept. of Forest Sciences, Vancouver, BC; Andrew Eckert, University of California Davis, Section of Plenary Paper Evolution and Ecology, Davis, CA; Stacy Jorgensen, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Department of Geography, Manoa, HI; Anna Schoettle, USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fort Collins, CO; Sally Aitken, University of British Columbia, Dept. of Forest Sciences, Vancouver, BC Abstract—Conservation genetics examines the biophysical factors population structure using molecular markers and quanti- influencing genetic processes and uses that information to conserve tative traits and assessing how these measures are affected and maintain the evolutionary potential of species and popula- by ecological changes. Genetic diversity is influenced by the tions. Here we review published and unpublished literature on the evolutionary forces of mutation, selection, migration, and conservation genetics of seven North American high-elevation drift, which impact within- and among-population genetic five-needle pines. Although these species are widely distributed across much of western North America, many face considerable diversity in differing ways. Discussions of how these forces conservation challenges: they are not valued for timber, yet they impact genetic diversity can be found in many genetics texts have high ecological value; they are susceptible to the introduced (for example Frankham and others 2002; Hartl and Clark disease white pine blister rust (caused by the fungus Cronartium 1989) and will not be discussed here. ribicola) and endemic-turned-epidemic pests; and some are affect- ed by habitat fragmentation and successional replacement by other Why Is Genetic Diversity Important? species.