Summary of the Hearing with the London Cremation Company July

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surrey Supply Teachers

Magazine of the Knaphill Residents’ Association Summer 2017 Issue 56 news knaphill Cover photo: Jim Binney Follow us on Twitter @KnaphillKRA Keep up to date www.knaphill.org Surrey Supply Teachers A professional, friendly agency recruiting Primary and Secondary supply teachers, Nursery staff and Teaching Assistants to work for us in a variety of local schools. Both full and part time work is available on a day to day and longer term basis. and you can work as much or as little as you like. 01932 254261 [email protected] www.surreysupplyteachers.co.uk For a Free Design Consultation Call 01483 461480 Frimley Woking Guildford www.notjustkitchenideas.com Knaphill News Summer 2017 3 Knaphill News knaphill.org From the Chairman Knaphill News Spring 2015 It was good to see a number of residents attend our AGM and presentation3 Editor KnaphillJim BinneyNews From the Chairman Assistant Editor knaphill.orgSue Stocker Veryby David soon Munro, you willElected be castingPolice Commissioner your vote in forthe Surrey. General Not surprisingly Advertising Paul Webster Electionthere were and a number receiving of tricky knocks questions on the for door David from on local local police matters. Artwork Editor Tim BurdettSue Stocker politicians.Also thanks On to page Mal 5,Foster you will our see local an excellent novelist contribution speaking on his books [email protected] Fat Crow fromincluding our Planninghis new one guru coming Phil Stubbs, out this including summer. reference to Design & Layout FatCrow.co.uk the 650 new homes recently built or being built in the A322 Published by [email protected] Residents’ Association corridorTurning to and Facebook the infrastructure we recently thatlaunched is required a Knaphill to meet Community the Facebook demandsPage with ofthe such help a oflarge our influx KRA Editors. -

View the 180 Listed Buildings And

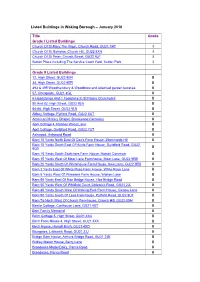

Listed Buildings in Woking Borough – January 2010 Title Grade Grade I Listed Buildings Church Of St Mary The Virgin, Church Road, GU21 1RT I Church Of St Nicholas, Church Hill, GU22 8XH I Church Of St Peter, Church Street, GU22 9JF I Sutton Place Including The Service Court Yard, Sutton Park I Grade II Listed Buildings 12, High Street, GU22 9ER II 34, High Street, GU22 9ER II 493 & 495 Woodhambury & Woodbrow and attached garden terraces II 57, Cheapside, GU21 4GL II 6 Headstones And 1 Footstone In St Peters Churchyard II 80 And 82, High Street, GU22 9LN II 84-88, High Street, GU22 9LN II Abbey Cottage, Pyrford Road, GU22 8UT II American Military Chapel, Brookwood Cemetery II April Cottage 4, Runtley Wood Lane II April Cottage, Guildford Road, GU22 7UT II Ashwood, Ashwood Road II Barn 10 Yards North East Of Cox's Farm House, Blanchards Hill II Barn 15 Yards South East Of Hunts Farm House, Guildford Road, GU22 II 9QX Barn 15 Yards South Scotchers Farm House, Horsell Common II Barn 15 Yards West Of Moor Lane Farmhouse, Moor Lane, GU22 9RB II Barn 20 Yards South Of Whitehouse Farm House, New Lane, GU22 9RB II Barn 3 Yards East Of White Rose Farm House, White Rose Lane II Barn 5 Yards West Of Wheelers Farm House, Warren Lane II Barn 50 Yards East Of Hoe Bridge House, Hoe Bridge Road II Barn 50 Yards West Of Whitfield Court, Littlewick Road, GU21 2JL II Barn 80 Yards South West Of Woking Park Farm House, Carters Lane II Barn 90 Yards South Of Lees Farmhouse, Pyrford Road, GU22 8UT II Barn To North West Of Church Farmhouse, Church Hill, GU22 -

Pyrford Church of England Primary School 27 January 2017

Pyrford Church of England Primary School 27 January 2017 Good morning - well a marginally quieter week than last week although still busy. Earlier this week you should have received an email to inform you that we will be closing the school on Monday 6th February. This is not a decision we have taken lightly, In this week’s however with a large number of staff wishing to attend the funeral, we were unable to newsletter: staff the school. I have been liaising closely with Mrs Edis' family this week regarding Golden Book arrangements for the funeral. A service will be held at 9.30am at Woking Crematorium for family and close friends including some staff members. Sainsburys Active Kids There will be a celebration of the life of Mrs Edis held at St Mary's Church in Byfleet at Quiz Night 11am on Monday 6th February and afterwards until 4pm in St Mary's Church Hall. The family have stressed that parents are most welcome to join the celebration of life Staff Vacancy service, which they would like to be a joyful occasion. A number of us will be speaking Young Voices about Mrs Edis and we will be sharing some thoughts, poems and prayers written by Community the children. Notices Demolition of the old school has been in full swing again this week. It is proposed that Diary dates parking and play space will be made available in the next two weeks at the Peatmore end of the school. We had hoped to be there a little earlier but are waiting for the gas board to connect/disconnect various gas supplies. -

Dates for Your Diary

WHAT’S ON Morning Prayer takes place at St Peter’s on Mondays and Thursdays at 9.00am, All Souls’ on Tuesdays at 9.00am and St Marks on Wednesdays at 8.00am Monday 3 Dec 3.15pm Refresh Café St Mark’s Tuesday 4 Dec 9.00am Hearing Aid Clinic St Peter’s Tuesday 4 Dec 10.00am Tots St Mark’s Tuesday 4 Dec 11.30am Moorcroft Prayer Moorcroft Tuesday 4 Dec 2.15pm Women’s Fellowship St Mark’s Wednesday 5 Dec 10.00am Sparks Church Centre Sunday 2 December 2018 Advent Sunday Friday 7 Dec 7.30pm Guide Dog Carol Service St Peter’s Friday 7 – Sunday 9 December Christmas Tree Festival St Peter’s Sunday 9 Dec 3.30pm Carols at Kingsleigh Kingsleigh Care Home * CHRISTMAS CARDS FOR THE PARISH * We aim to deliver Christmas Cards with details of our Sunday 9 December– Second Sunday in Advent Christmas services to all homes in the parish, but need 9.30am All Souls’ Holy Communion (CW) your help. The cards are available to be delivered now 10.00am St Peter’s Nativity Service and are bundled up by roads so please choose one or 11.00am St Mark’s Holy Communion (CW) two roads to deliver to, if you can, to spread the load. 6.30pm St Peter’s Holy Communion (BCP) It would be helpful if they could be delivered before the Christmas Tree Festival, which starts on Friday 7 December. PARISH STAFF * GUIDE DOGS ASSOCIATION CAROL SERVICE * Vicar Jonathan Thomas Telephone: 01483 762707 Friday 7 December 7.30pm at St Peter’s The Vicarage, 66 Westfield Road, Woking GU22 9NG If you have never been to this annual Carol service on behalf of the email: [email protected] Day Off – Saturday Guide Dogs Association, make sure you come this year as it is a very special occasion. -

KMC Magazine Easter 2021

It seems to have been a long winter and yet that said, looking back now, it seems to have gone quite quickly. Of course, the speed at which time passes will all depend on what each of us has been able to do in the last 3 months. In the Lockdown Stories and KMC Family News, a couple of people decided to really challenge themselves and came out winners. Others have immersed themselves in their individual interests both to take their minds off what has been happening and keep boredom at bay. I wish I could say I have been as productive as Sheila & John Mynard but I can’t, so I won’t! The sad passing of Helen Baker is reflected in this issue and I hope you will find the various items in memory of Helen, including one written by Helen herself, both interesting, informative and appropriate. The article on Supporting Charities is worthy of note. Many charities have suffered a decline in donations throughout the pandemic for obvious reasons. Lynda Shore brings to our attention several charities which she would like us to remember at this time including Christian Aid. Easter is a time to celebrate the promise of eternal life through Christ’s death and resurrection with Easter Day coming as a reminder of renewal and life restored. Spring started on 20 March this year with Easter following close on its heels so making the feeling of renewal especially strong. This sense of rebirth will be felt even more keenly, I would suggest, because we will hopefully soon be slowly emerging from lockdown. -

Wardle – the Long Distance Railway Funeral

Henry Wardle – The long distance Railway Funeral Henry Wardle (1832 – 16 February 1892) Wardle was born at Twyford, Berkshire, the son of Francis Wardle and his wife Elizabeth Billinge. In 1853 at the age of 21 he went into partnership with Thomas Fosbrooke Salt in the Burton upon Trent brewery Thomas Salt and Co. Wardle married Thomas Fosbrooke Salt’s daughter Mary Ellen Salt in 1864.They lived at Winshill. He was for many years active in the town’s civic affairs as a Town Commissioner and then an alderman after Burton became a municipal borough in 1878. He was a J. P. for Derbyshire and Staffordshire. Wardle was elected as the Member of Parliament (MP) for South Derbyshire constituency at the 1885 general election. He held the seat until his death in Burton upon Trent in 1892 aged 60. The Funeral Mr. H. Wardle funeral took place on Saturday 20th February 1892. He wished that his body should be cremated. Arangements where made with Woking crematorium The body, which was enclosed in a pine coffin, remained at Highfield, his home at Burton-on-Trent, until about half past nine on Friday night. When six old employees were selected from different departments of the brewery to reverently convey it to the brewery sidings. Where a special van and a Saloon were standing. The corpse was placed in the van, and guard was kept over it during the night. It had been arranged that Messrs. F. Wardle, H. Wardle, E. D. Salt, W. C. Salt, H.G. Tomlinson, H.E Bridgman, and E. -

Information for Pregnancy Loss May 2018A

Information for Pregnancy Loss Considerations and advice for you at this difficult time Women’s Health and Paediatrics Page 12 Patient Information Information for Pregnancy Loss This leaflet is designed to give you some practical information you will need leading up to and immediately following the birth. This leaflet is intended to support the information that you will receive from healthcare professionals. We aim to provide care that will meet your individual needs. If you have any specific needs, please let us know what your requirements are, and how we can help you. Introduction This is an emotional time for you and the feelings that you may experience can vary from shock to disbelief. These feelings may also vary between you and your partner. When you come into hospital you and your partner will, when possible, be taken to a room off the Labour Ward called the Daffodil Room. Whilst you may feel this is a little isolated, the Further Information room is situated away from other women to allow you privacy We endeavour to provide an excellent service at all times, but should you have at this sensitive time. The room has a sofa bed so your partner any concerns please, in the first instance, raise these with the Matron, Senior can stay with you at all times and a call bell is in place for you Nurse or Manager on duty. to call your midwife at any time. If they cannot resolve your concern, please contact our Patient Experience Team on 01932 723553 or email [email protected] . -

Stuart Wilson

Farewell Ceremony followed by Celebration of Life Ceremony for Stuart Wilson 30th October 1951 – 2nd August 2018 Held at Woking Crematorium and The Lightbox on Monday 3rd September 2018 10.15am Tribute from the Farewell Ceremony at the crematorium This ceremony is our more formal farewell to Stuart and will be followed be a full celebration of the inspirational and free-spirited life he led - a life that has touched the lives of everyone here today, and so many others who were lucky enough to spend time with him. Stuart was described recently by his sister-in-law Janet as “vibrant, witty and naughty” and we’ll hear several stories later today that centre on these delightful characteristics of his. From a young age, Stuart knew exactly who he was and where he was going. He followed his destiny, or shaped his future – however you choose to see it – by developing his immense natural talent for art. We all know what an incredible collection of work he went on to produce over his lifetime. We can only be thankful that he chose to explore this extraordinary gift and in doing so shared it with the rest of us. A funny, blunt, sometimes stubborn man with a gift for malapropisms and great personal charisma, Stuart was a person who generally made an immediate and unforgettable impression on those he met. He refused to be dictated to – he had little time for the formality of suits and ceremonies. Our gathering here today will honour him in its simplicity and its straightforward reflections on what he meant, and will continue to mean, to those he leaves behind. -

November News 2020

BROOKWOOD CHRISTMAS FOODBANK COLLECTION – CAN YOU HELP? BROOKWOOD An appeal by Trudi & Darren: What a very strange year it has been with Covid-19 and lockdown. These two combined elements have resulted in an unprecedented rise in service users to Woking Foodbank. We have given much thought as to whether NEWS to run the campaign this year due to Covid, but we have decided to push ahead with it as our local communities need our help more than ever this November 2020 year. Woking Foodbank have been adapting to the new government rules and delivering lots of food parcels to the elderly, those who have been shielding for health reasons, and those with little or no income due to being furloughed or indeed having been made redundant. BROOKWOOD BABIES AND The campaign will commence on 28 October and finish on 5 December. EDITORIAL If you can help in any way with non-perishable items that would be TODDLERS PLAYGROUP fantastic, or alternatively a cash donation. The cash may be used to Welcome to the November edition of purchase non-perishables or indeed put towards paying the rent on their Brookwood News and many thanks to new premises. all our contributors. And many thanks also to you, our readers; we hope you If you would like to provide a food parcel, please attach a label with your promote your business through all variations of social media throughout are keeping well in these difficult name and address so we can thank you personally. Drop-off points are the campaign. times. currently Brookwood Club and also Bakers Dozen/Post Office during working hours, both within the village. -

Horsell LOCATION: Former Garden Centre, Mimbridge, Station Road

20 OCTOBER 2020 PLANNING COMMITTEE 6a PLAN/2020/0405 WARD: Horsell LOCATION: Former Garden Centre, Mimbridge, Station Road, Chobham, GU24 8AS PROPOSAL: Outline application with all matters reserved for the erection of a crematorium with associated facilities. APPLICANT: Alan Greenwood & Sons OFFICER: James Kidger REASON FOR REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE The application is brought before the Committee at the request of Councillors Chrystie and Hussain. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT Outline planning permission, with all matters reserved, is sought for the erection of a crematorium and associated facilities. PLANNING STATUS Contaminated Land Flood Zone 2 Green Belt Thames Basin Heaths Special Protection Area (TBH SPA) Zone A (0-400m) RECOMMENDATION REFUSE planning permission. SITE DESCRIPTION The site is located at the southerly end of Mimbridge, just north of the Addlestone Bourne, and accessed from Chobham Road to the east. It is within the Green Belt and is also within 400m (Zone A) of the Thames Basin Heaths Special Protection Area (TBH SPA). PLANNING HISTORY WO93/0391 – Certificate of lawfulness (existing use) for the importation, storage, screening and sale of soils – approved 26th November 1993. CONSULTATIONS Contaminated Land Officer – No objection subject to recommended conditions. Drainage & Flood Risk – Objection. Environment Agency – No objection subject to recommended conditions. 20 OCTOBER 2020 PLANNING COMMITTEE Environmental Health – No objection at outline stage. Highway Authority – Objection. Natural England – No objection. Surrey -

Dates for Your Diary

WHAT’S ON St Peter’s is open from 9.00am – 12 noon Mon – Fri, 1000am – 6.00pm on Saturdays and 11.30am – 6.00pm Sundays. All Souls’ is open from 9.00am – 6.00pm on Tue & Sun Today 6.30pm Youth BBQ 64 Fairfax Road Monday 3 Sep 9.00am Morning Prayer St Peter’s Tuesday 4 Sep 9.00am Morning Prayer All Souls’ Tuesday 4 Sep 9.00am Hearing Aid Clinic St Peter’s Wednesday 5 Sep 8.00am Morning Prayer St Mark’s Sunday 2 September 2018 Trinity 14 Wednesday 5 Sep 10.00am Sparks Church Centre Thursday 6 Sep 9.00am Morning Prayer St Peter’s Do not add to what I command you and do not subtract from it, but keep the commands of the Lord your God that I give you. Observe them carefully, for Sunday 9 September - Trinity 15 this will show your wisdom and understanding. 9.30am All Souls’ Holy Communion (BCP) Deuteronomy 4: 2, 6a 10.00am St Peter’s All-Age Worship * BEACH TRIP – NEXT SUNDAY 9 SEPTEMBER * No service at St Mark’s – see entry for Beach Trip The weather forecast is looking good and there are plenty of places left on the 6.30pm St Peter’s Holy Communion (BCP) minibuses, so why not come on our beach trip to West Wittering and enjoy a BBQ, games, sand activities and a service on the beach. The free minibuses will leave St Mark’s around 11.15am and we aim to be back in Woking by 7.00pm. Numbers are PARISH STAFF limited, both on the minibus and for catering purposes, so please sign up whether Vicar Jonathan Thomas Telephone: 01483 762707 coming on the minibus or under your own steam. -

Woking Remembers on Sunday 11 November 2018

Woking remembers on Sunday 11 November 2018 Celebrate Woking dates for your diary Winter 2018 @wokingcouncil www.facebook.com/wokingbc Please read and then recycle www.woking.gov.uk/thewokingmagazine AWARD WINNING TOP TECH UK 2014/15 AllAll PartsParts & LabourLaboour GuaranteedGuaranteed ServicingServicing toto ManufacturersManufacturers StandardsStandards MOTsMOTTss – includingding Diesels ElectronicElectronic FaultFauult DiagnosisDiagnosis Brakes,Br akes , Exhausts,Exhauusts, ClutchesClutches & TyresTTyryres Diesel PoweredPowereed TuningTuning ECU RemappingRemappiing AirAir ConditioningConditioning ServicingServicing ANewNe w Rolling Road RobinRobin HoodHood RdRd t KnaphillKnaphill t WokingWoking t GU21GU21 2LX2LX Winter | 2018 Introduction Contents News in brief Welcome to the Latest new from across Woking 4 winter edition of The Woking Open letter to residents of Magazine – Woking Borough Council 10 your window on Development in Woking Town Centre Woking Borough White Ribbons against domestic abuse 11 White Ribbon Day 25 November This issue is packed with enough great content to keep you entertained throughout the colder months. Celebrate Woking We could not enter the month of November 2018 Your winter social and cultural 12 without acknowledging our fallen heroes of both calendar world wars and thereafter. This year is exactly 100 years since the Armistice, and our annual Money Matters The annual report of the 14 Remembrance Service will mark the occasion with Council’s finances all of the dignity that such an anniversary deserves. Do pick up a poppy and join us in Hoe Valley School and Jubilee Square to pay your respects. Woking Sports Box 1 6 This November is also W hite R ibb on Day, a A brighter, healthier future for all campaign to help prevent male violence towards women.