Epidemiology of Bloodstream Infections and Predictive Factors Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C-Reactive Protein and Albumin Kinetics Before Community-Acquired Bloodstream Infections – Cambridge.Org/Hyg a Danish Population-Based Cohort Study

Epidemiology and Infection C-reactive protein and albumin kinetics before community-acquired bloodstream infections – cambridge.org/hyg a Danish population-based cohort study 1 1,2,3 1 4 5 Original Paper O. S. Garvik , P. Póvoa , B. Magnussen , P. J. Vinholt , C. Pedersen , T. G. Jensen6, H. J. Kolmos6, A. T. Lassen7 and K. O. Gradel1 Cite this article: Garvik OS, Póvoa P, Magnussen B, Vinholt PJ, Pedersen C, Jensen 1Research Unit of Clinical Epidemiology, Institute of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, and Center TG, Kolmos HJ, Lassen AT, Gradel KO (2020). for Clinical Epidemiology, Odense University Hospital, Kløvervænget 30, Entrance 216, ground floor, 5000 Odense C-reactive protein and albumin kinetics before 2 community-acquired bloodstream infections – C, Denmark; NOVA Medical School, New University of Lisbon, Campo Mártires da Pátria 130, 1169-056 Lisbon, 3 a Danish population-based cohort study. Portugal; Polyvalent Intensive Care Unit, São Francisco Xavier Hospital, CHLO, Estrada do Forte do Alto do Duque, 4 Epidemiology and Infection 148,e38,1–6. 1449-005 Lisbon, Portugal; Department of Clinical Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Odense University Hospital, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268820000291 Sdr. Boulevard 29, entrance 40, 5000 Odense C, Denmark; 5Department of Infectious Diseases, Odense University Hospital, Sdr. Boulevard 29, entrance 20, 5000 Odense C, Denmark; 6Department of Clinical Microbiology, Odense Received: 30 October 2019 University Hospital, J.B. Winsløws Vej 21, 2nd floor, 5000 Odense C, Denmark and 7Department of Emergency Revised: 16 January 2020 Medicine, Odense University Hospital, Kløvervænget 25, entrance 63-65, 5000 Odense C, Denmark Accepted: 22 January 2020 Key words: Abstract Albumin; C-reactive protein; community acquired bloodstream infections Early changes in biomarker levels probably occur before bloodstream infection (BSI) is diag- nosed. -

BLOOD INFECTIONS INTRODUCTION TYPES Of

BLOOD INFECTIONS Please supplement and learn theory on the basis of the lecture, Mim’s book and supplementary materials before class!!! INTRODUCTION PRINCIPLE: UNDER NATURAL CONDITIONS BLOOD IS STERILE IMPORTANT TERMS: Nosocomial infection ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Bacteremia ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Viremia …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Fungemia ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Sepsis …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. SIRS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. MODS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. ARDS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… DIC ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. CRBI …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. BSI ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. TYPES of BACTEREMIA .------------------------------------ ---------------------------------- ---------------------------------- •Examples: •Examples: •Examples: •-------------------------------------- •------------------------------------- •------------------------------------ -------------------------------------- •-------------------------------------- •-------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -------------------------------------- -

Bacterial Bloodstream Infections in HIV-Infected Adults Attending a Lagos Teaching Hospital

J HEALTH POPUL NUTR 2010 Aug;28(4):318-326 ©INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR DIARRHOEAL ISSN 1606-0997 | $ 5.00+0.20 DISEASE RESEARCH, BANGLADESH Bacterial Bloodstream Infections in HIV-infected Adults Attending a Lagos Teaching Hospital Adeleye I. Adeyemi1, Akanmu A. Sulaiman2, Bamiro B. Solomon3, Obosi A. Chinedu1, and Inem A. Victor4 1Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Science, University of Lagos, Akoka, Nigeria, 2Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba, Nigeria, 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Bacteriology Research Laboratory, College of Medicine, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria, and 4Institute of Child Health and Primary Care, Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Idi-Araba, Nigeria ABSTRACT An investigation was carried out during October 2005–September 2006 to determine the prevalence of bloodstream infections in patients attending the outpatient department of the HIV/AIDS clinic at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital in Nigeria. Two hundred and one patients—86 males and 115 females—aged 14-65 years were recruited for the study. Serological diagnosis was carried out on them to confirm their HIV status. Their CD4 counts were done using the micromagnetic bead method. Twenty mL of venous blood sample collected from each patient was inoculated into a pair of Oxoid Signal blood culture bottles for 2-14 days. Thereafter, 0.1 mL of the sample was plated in duplicates on MacConkey, blood and chocolate agar media and incubated at 37 °C for 18-24 hours. The CD4+ counts were generally low as 67% of 140 patients sampled had <200 cells/µL of blood. Twenty-six bacterial isolates were obtained from the blood samples and comprised 15 (58%) coagulase-negative staphylococci as follows: Staphylococcus epidermidis (7), S. -

Pdfs/ Ommended That Initial Cultures Focus on Common Pathogens, Pscmanual/9Pscssicurrent.Pdf)

Clinical Infectious Diseases IDSA GUIDELINE A Guide to Utilization of the Microbiology Laboratory for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases: 2018 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Society for Microbiologya J. Michael Miller,1 Matthew J. Binnicker,2 Sheldon Campbell,3 Karen C. Carroll,4 Kimberle C. Chapin,5 Peter H. Gilligan,6 Mark D. Gonzalez,7 Robert C. Jerris,7 Sue C. Kehl,8 Robin Patel,2 Bobbi S. Pritt,2 Sandra S. Richter,9 Barbara Robinson-Dunn,10 Joseph D. Schwartzman,11 James W. Snyder,12 Sam Telford III,13 Elitza S. Theel,2 Richard B. Thomson Jr,14 Melvin P. Weinstein,15 and Joseph D. Yao2 1Microbiology Technical Services, LLC, Dunwoody, Georgia; 2Division of Clinical Microbiology, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota; 3Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut; 4Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland; 5Department of Pathology, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence; 6Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; 7Department of Pathology, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Georgia; 8Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee; 9Department of Laboratory Medicine, Cleveland Clinic, Ohio; 10Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Beaumont Health, Royal Oak, Michigan; 11Dartmouth- Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire; 12Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Louisville, Kentucky; 13Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health, Tufts University, North Grafton, Massachusetts; 14Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Illinois; and 15Departments of Medicine and Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey Contents Introduction and Executive Summary I. -

Fungal Sepsis: Optimizing Antifungal Therapy in the Critical Care Setting

Fungal Sepsis: Optimizing Antifungal Therapy in the Critical Care Setting a b,c, Alexander Lepak, MD , David Andes, MD * KEYWORDS Invasive candidiasis Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics Therapy Source control Invasive fungal infections (IFI) and fungal sepsis in the intensive care unit (ICU) are increasing and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. In this setting, IFI are predominantly caused by Candida species. Currently, candidemia represents the fourth most common health care–associated blood stream infection.1–3 With increasingly immunocompromised patient populations, other fungal species such as Aspergillus species, Pneumocystis jiroveci, Cryptococcus, Zygomycetes, Fusarium species, and Scedosporium species have emerged.4–9 However, this review focuses on invasive candidiasis (IC). Multiple retrospective studies have examined the crude mortality in patients with candidemia and identified rates ranging from 46% to 75%.3 In many instances, this is partly caused by severe underlying comorbidities. Carefully matched, retrospective cohort studies have been undertaken to estimate mortality attributable to candidemia and report rates ranging from 10% to 49%.10–15 Resource use associated with this infection is also significant. Estimates from numerous studies suggest the added hospital cost is as much as $40,000 per case.10–12,16–20 Overall attributable costs are difficult to calculate with precision, but have been estimated to be close to 1 billion dollars in the United States annually.21 a University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5218, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA b Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5211, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA c Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5211, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA * Corresponding author. -

Bloodstream Infections Surveillance Module for Rural Hospitals and Non-Acute Settings

TASMANIAN INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL UNIT Bloodstream Infections Surveillance Module for rural hospitals and non-acute settings. Version 1 Department of Health and Human Services Bloodstream infection - surveillance module for rural hospitals and non-acute settings. Tasmanian Infection Prevention and Control Unit (TIPCU) Department of Health and Human Services, Tasmania Published 2013 Copyright—Department of Health and Human Services Editors • Anne Wells, TIPCU • Fiona Wilson, TIPCU Suggested citation: Wells A., Wilson F. (2013). Bloodstream infection – surveillance module for rural hospitals and non- acute settings. Hobart: Department of Health and Human Services. TASMANIAN INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL UNIT Population Health Department of Health and Human Services GPO Box 125 Hobart 7001 Ph: 6222 7779 Fax: 6233 0553 www.dhhs.tas.gov.au/tipcu 1 Contents Blood stream infection surveillance ........................................................................................................ 3 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Aims .................................................................................................................................................... 3 Inclusion criteria.................................................................................................................................. 3 Exclusion criteria................................................................................................................................ -

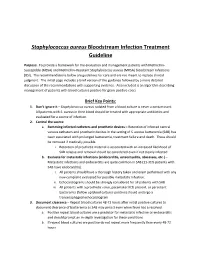

Staphylococcus Aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline

Staphylococcus aureus Bloodstream Infection Treatment Guideline Purpose: To provide a framework for the evaluation and management patients with Methicillin- Susceptible (MSSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bloodstream infections (BSI). The recommendations below are guidelines for care and are not meant to replace clinical judgment. The initial page includes a brief version of the guidance followed by a more detailed discussion of the recommendations with supporting evidence. Also included is an algorithm describing management of patients with blood cultures positive for gram-positive cocci. Brief Key Points: 1. Don’t ignore it – Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a blood culture is never a contaminant. All patients with S. aureus in their blood should be treated with appropriate antibiotics and evaluated for a source of infection. 2. Control the source a. Removing infected catheters and prosthetic devices – Retention of infected central venous catheters and prosthetic devices in the setting of S. aureus bacteremia (SAB) has been associated with prolonged bacteremia, treatment failure and death. These should be removed if medically possible. i. Retention of prosthetic material is associated with an increased likelihood of SAB relapse and removal should be considered even if not clearly infected b. Evaluate for metastatic infections (endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscesses, etc.) – Metastatic infections and endocarditis are quite common in SAB (11-31% patients with SAB have endocarditis). i. All patients should have a thorough history taken and exam performed with any new complaint evaluated for possible metastatic infection. ii. Echocardiograms should be strongly considered for all patients with SAB iii. All patients with a prosthetic valve, pacemaker/ICD present, or persistent bacteremia (follow up blood cultures positive) should undergo a transesophageal echocardiogram 3. -

Dr. Terry W. Pearson ABSTRACT Procyclic Culture Forms Of

i i Supervisor: Dr. Terry W. Pearson ABSTRACT Procyclic culture forms of Trypanosoma brucei species and antibodies to these parasites were used in developing antibody-detection and antigen-detection assays for diagnosis of African human sleeping sickness. An agglutination assay using live procyclic trypanosomes- the Procyclic Agglutination Trypanosomiasis Test (PATT) was developed for detecting anti-trypanosome antibodies in the sera of trypanosome-infected vervet monkeys and humans. Antibodies to procyclic surface antigens were detected by the PATT in sera of vervet monkeys as early as 7 days post-infection with T. b. rhodesiense. Positive agglutination titres were obtained with sera from monkeys with active, untreated infections and with sera taken soon after successful drag cure. Similar positive agglutination results were also observed using the PATT with sera from T. b.gambiense- infected patients from Cote d'Ivoire and Sudan and with documented sera from T. b. rhodesiense—infected patients from Kenya. No agglutination reactions were observed with preinfection sera from vervet monk, ys, with sera from uninfected Canadians or with sera from Americans working in endemic areas. Together these results confirm the diagnostic value of using procyclic trypanosomes to detect anti-trypanosome antibodies in. human African sleeping sickness. A double antibody sandwich ELISA using monoclonal antibodies and polyclonal rabbit antibodies to the surface membrane antigens of procyclic trypanosomes was developed. This assay detected circulating trypanosomal antigens in the sera of trypanosome-infected mice and in the sera from parasite-infected patients. However, limited success was obtained with this sandwich ELISA when tested on a larger repertoire of sera from infected humans. -

For Bloodstream Infections, Rapid Molecular Testing Improves Patient Outcomes and Lowers Costs

White Paper For Bloodstream Infections, Rapid Molecular Testing Improves Patient Outcomes and Lowers Costs Bloodstream infections are a potentially deadly scenario for Gram-negative bacteria. Both tests also detect several markers of healthcare facilities. They can be caused by a wide range of antibiotic resistance. These tests together detect 90% to 95% of what pathogens, making testing difficult. But they also require urgent causes Gram-positive and Gram-negative bloodstream infections. treatment — patients with sepsis, for example, face a 7.6% increase in risk of death for each hour that optimal treatment is delayed.1 Results from these tests can be used with the local antibiogram to Finally, these infections are increasingly associated with the guide treatment selection, based on the pathogen identified as well antibiotic resistance crisis. as drug-resistance profiles. Just as importantly, they can be used to recommend no treatment. For example, Gram-positive bacteria are One of the biggest obstacles to improving the diagnosis of a common source of contamination during blood draws; they lead to bloodstream infections is how long it takes to receive clinically a number of positive blood cultures that are not clinically relevant. actionable results. After blood cultures come back positive, clinical In facilities without rapid testing, physicians typically treat these lab teams perform conventional ID and susceptibility testing that patients with antibiotics, contributing to the antibiotic resistance can take two to four days to generate useful information about epidemic. Rapid results from VERIGENE bloodstream infection tests the pathogen species and any relevant drug resistance. That’s can quickly highlight contaminants, making it possible to avoid simply too much of a delay to contribute meaningfully to treatment unnecessary use of antibiotics. -

Follow-Up Blood Cultures in Gram-Negative Bacteremia: Are They Needed? Christina N

Clinical Infectious Diseases MAJOR ARTICLE Follow-up Blood Cultures in Gram-Negative Bacteremia: Are They Needed? Christina N. Canzoneri, Bobak J. Akhavan, Zehra Tosur, Pedro E. Alcedo Andrade, and Gabriel M. Aisenberg XX Department of General Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston XXXX Background. Bloodstream infections remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) bacter- emia is typically transient and usually resolves rapidly after the initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy and source control. The optimal duration of treatment and utility of follow-up blood cultures (FUBC) have not been studied in detail. Currently, the manage- ment of gram-negative bacteremia is determined by clinical judgment. To investigate the value of repeat blood cultures, we analyzed Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/cid/article-abstract/65/11/1776/4036391 by guest on 22 October 2019 500 episodes of bacteremia to determine frequency of FUBC and identify risk factors for persistent bacteremia. Methods. Of 500 episodes of bacteremia, we retrospectively analyzed 383 (77%) that had at least 1 FUBC. We sought infor- mation regarding presumed source of bacteremia, antibiotic status at the time of FUBC, antibiotic susceptibility, presence of fever, comorbidities (intravenous central lines, urinary catheters, diabetes mellitus, AIDS, end-stage renal disease, and cirrhosis), need for intensive care, and mortality. Results. Antibiotic use did not affect the rate of positivity of FUBC, unless bacteria were not sensitive to empiric antibiotic. Fever on the day of FUBC was associated with higher rates of positive FUBC for gram-positive cocci (GPC) but not GNB. -

MEDICINE PLUS SURGERY TREATS an UNUSUAL CASE of FUNGAL ENDOPHTHALMITIS Careful Attention to the Patient’S History and Persistent Follow-Up Made for a Positive Result

FEATURE MEDICINE PLUS SURGERY TREATS AN UNUSUAL CASE OF FUNGAL ENDOPHTHALMITIS Careful attention to the patient’s history and persistent follow-up made for a positive result. BY ADITYA MEHTA, MD, AND YU HYON KIM, MD Extreme morning sickness, hyperemesis gravidarum requiring TPN. She returned 2 weeks or hyperemesis gravidarum, later with complaints of blurry vision in her right eye (OD). is a complication of The patient had no previous ocular history or history pregnancy characterized by of intravenous drug use. HIV test performed earlier in the severe nausea and vomit- pregnancy was negative. On presentation, visual acuity (VA) ing, weight loss, and even was 20/70 OD and 20/20 in her left eye (OS). Her intraocular dehydration. Whereas pressure (IOP) was 19 mm Hg OD and 20 mm Hg OS, and mild cases of hyperemesis there was no relative afferent pupillary defect. The external gravidarum can be treated with dietary changes, rest, and examination was unremarkable. Anterior chamber examina- antacids, more severe cases can require hospitalization and tion exhibited 1+ cell OD. intravenous nutrition. The following case report describes a young pregnant woman with fungal endophthalmitis in the setting of candidemia from fungal endocarditis after receiv- ing total parenteral nutrition (TPN). CASE REPORT A 31-year-old black woman, at 24 weeks gestational age, was admitted to the San Antonio Military Medical Center for AT A GLANCE • Ophthalmologic findings of C. albicans endophthalmitis have a strong association with disseminated candidiasis, especially in the setting of predisposing factors. • In this case report, prompt vitrectomy and intravitreal injection of amphotericin led to Figure 1. -

Alabama Department of Public Health Annual Report 2020

ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC HEALTH ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Alabama Department of Public Health ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 STATE COMMITTEE OF PUBLIC HEALTH Gary F. Leung, M.D. Gregory W. Ayers, M.D. Scott Harris, M.D., M.P.H. Chair Vice Chair Secretary Eli L. Brown, M.D. Hernando D. Michael T. Beverly Jordan, M.D. Mark H. LeQuire, M.D. Carter, M.D. Flanagan, M.D. Patrick O’Neill, M.D. Dick Owens, M.D. Charles M.A. “Max” William Jay Jane Ann Rogers, IV, M.D. Suggs, M.D. Weida, M.D. James C. Wright, D.V.M. Stuart A. Joseph Marchant Greg Gillian, P.E., P.L.S. Council on Animal and Lockwood, D.M.D. Council on Health Council on Prevention Environmental Health Council on Costs, Administration of Disease and Dental Health and Organization Medical Care A LETTER FROM THE STATE HEALTH OFFICER The Honorable Kay Ivey Governor of Alabama State Capitol Montgomery, Alabama 36130 Dear Governor Ivey: I am pleased to present the Annual Report of the Alabama Department emergency was declared, ADPH’s quick response ensured essential of Public Health (ADPH) for 2020. This report reflects the rapid and services were provided. Some programs implemented a telephone visit unparalleled pandemic response of ADPH during this year when the model. The ALL Kids Program extended coverage for up to 60 days for challenge of protecting the health of Alabamians became paramount enrollees who were due to renew during the spring months, and other as we worked to mitigate the effects of the largest outbreak of a single allowances were made.