Studies in Economic Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Sarvesh Bandhu

CURRICULUM VITAE Sarvesh Bandhu ACADEMIC EDUCATION Ph.D. Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi. Degree Awarded: August, 2020. Topic : Essays in Behavioral Voting Mechanisms Post-graduation Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi. Graduation Shri Ram College of Commerce, University of Delhi. RESEARCH Ph.D. Supervisor Prof. Arunava Sen, Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi. Areas of Game Theory Interest Behavioral and Experimental Economics Political Economy Mechanism Design Publication Bandhu, Sarvesh, Abhinaba Lahiri, and Anup Pramanik. \A characterization of status- quo rules in the binary social choice model." Economics Letters (2020): 109154. Working Papers Voting with Lying Costs: A Behavioral Approach to Overcome Gibbard-Satterthwaite The- orem. Random Strategy-Proof Voting with Lexicographic Extension. Easy is Hard: Two Stronger Implications of Obvious Strategy-Proofness Bounded Stochastic Response in Random Voting Models. [Joint Work] Work-in- Bottom non-manipulability: Relaxing incentive compatibility. [Joint Work] (A preliminary progress draft is available) Positive Result for Two-sided Matching with Minimum and Maximum Quotas under Di- chotomous Domain. [Joint work] (A preliminary draft is available) A New Solidarity Axiom for Binary Voting Model and its Characterization. (A preliminary draft is available) TEACHING EXPERIENCE Visiting Department of Economics, Ashoka University. Faculty January−April 2021. Course Taught at B.A. Hons. Economics: Introduction to Economics. Assistant Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University Professor August 2014−May 2016; February−May 2020 and November−December 2020 Courses Taught at M.A. Economics: Microeconomic Theory, Game Theory, Mathematical Economics. Teaching EPU, Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi. Assistant July 2016−June 2018. Courses Taught at M.S. Quantative Economics: Game Theory, Mathematical Programming, Environmental Economics Assistant Shri Ram College of Commerce, Delhi University. -

Implementation Theory*

Chapter 5 IMPLEMENTATION THEORY* ERIC MASKIN Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ, USA TOMAS SJOSTROM Department of Economics, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA Contents Abstract 238 Keywords 238 1. Introduction 239 2. Definitions 245 3. Nash implementation 247 3.1. Definitions 248 3.2. Monotonicity and no veto power 248 3.3. Necessary and sufficient conditions 250 3.4. Weak implementation 254 3.5. Strategy-proofness and rich domains of preferences 254 3.6. Unrestricted domain of strict preferences 256 3.7. Economic environments 257 3.8. Two agent implementation 259 4. Implementation with complete information: further topics 260 4.1. Refinements of Nash equilibrium 260 4.2. Virtual implementation 264 4.3. Mixed strategies 265 4.4. Extensive form mechanisms 267 4.5. Renegotiation 269 4.6. The planner as a player 275 5. Bayesian implementation 276 5.1. Definitions 276 5.2. Closure 277 5.3. Incentive compatibility 278 5.4. Bayesian monotonicity 279 * We are grateful to Sandeep Baliga, Luis Corch6n, Matt Jackson, Byungchae Rhee, Ariel Rubinstein, Ilya Segal, Hannu Vartiainen, Masahiro Watabe, and two referees, for helpful comments. Handbook of Social Choice and Welfare, Volume 1, Edited by K.J Arrow, A.K. Sen and K. Suzumura ( 2002 Elsevier Science B. V All rights reserved 238 E. Maskin and T: Sj'str6m 5.5. Non-parametric, robust and fault tolerant implementation 281 6. Concluding remarks 281 References 282 Abstract The implementation problem is the problem of designing a mechanism (game form) such that the equilibrium outcomes satisfy a criterion of social optimality embodied in a social choice rule. -

(Eds.) Foundations in Microeconomic Theory Hugo F

Matthew O. Jackson • Andrew McLennan (Eds.) Foundations in Microeconomic Theory Hugo F. Sonnenschein Matthew O. Jackson • Andrew McLennan (Eds.) Foundations in Microeconomic Theory A Volume in Honor of Hugo F. Sonnenschein ^ Springer Professor Matthew O. Jackson Professor Andrew McLennan Stanford University School of Economics Department of Economics University of Queensland Stanford, CA 94305-6072 Rm. 520, Colin Clark Building USA The University of Queensland [email protected] NSW 4072 Australia [email protected] ISBN: 978-3-540-74056-8 e-ISBN: 978-3"540-74057-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007941253 © 2008 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9,1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Cover design: WMX Design GmbH, Heidelberg Printed on acid-free paper 987654321 spnnger.com Contents Introduction 1 A Brief Biographical Sketch of Hugo F. Sonnenschein 5 1 Kevin C. Sontheimer on Hugo F. -

Ex Post Implementation in Environments with Private Goods

Theoretical Economics 1 (2006), 369–393 1555-7561/20060369 Ex post implementation in environments with private goods SUSHIL BIKHCHANDANI Anderson School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles We prove by construction that ex post incentive compatible mechanisms exist in a private goods setting with multi-dimensional signals and interdependent val- ues. The mechanism shares features with the generalized Vickrey auction of one- dimensional signal models. The construction implies that for environments with private goods, informational externalities (i.e., interdependent values) are com- patible with ex post equilibrium in the presence of multi-dimensional signals. KEYWORDS. Ex post incentive compatibility, multi-dimensional information, in- terdependent values. JEL CLASSIFICATION. D44. 1. INTRODUCTION In models of mechanism design with interdependent values, each player’s information is usually one dimensional. While this is convenient, it might not capture a significant element of the setting. For instance, suppose that agent A’s reservation value for an ob- ject is the sum of a private value, which is idiosyncratic to this agent, and a common value, which is the same for all agents in the model. Agent A’s private information con- sists of an estimate of the common value and a separate estimate of his private value. As other agents care only about A’s estimate of the common value, a one-dimensional statistic does not capture all of A’s private information that is relevant to every agent (including A).1 Therefore, it is important to test whether insights from the literature are robust to re- laxing the assumption that an agent’s private information is one dimensional. -

Implementation Via Rights Structures∗

Implementation via Rights Structures∗ Semih Korayy Kemal Yildiz z December 5, 2016 1 Introduction In the last four decades, implementation has been playing a steadily growing role in economic theory, whose importance we can hardly deny on our part. Every modern society is familiar with several institu- tional “real life” mechanisms as constitutions, legal codes, rules of corporate culture and social norms that aim to rule out socially undesirable outcomes and implement solely socially desirable ones under different circumstances. With such real life mechanisms, however, it is mostly the case that the objective that the mechanism aims to implement is rather fuzzy, social desirability of the objective is sometimes questionable, and the constructs that link the objective to the existing societal preference profile are usually rough. Even in economic regulation, which may be regarded as a field of relatively well posed problems in contrast to other areas, the design of a mechanism was done more or less by “trial and error” until the Seventies in the 20th century, as the objective of the mechanism was not precisely defined. Implementation theory takes the social objective – mostly represented by a social choice rule – as given. Thus, its point of departure is a precisely defined object, which the society is assumed to have somehow unanimously agreed upon. Moreover, the objective to be implemented relates the social desirability of an outcome to the current societal preference profile and other relevant parameters in a precise manner. It is exactly this ambitious aim, which gives rise to the main problem concerning implementation, as the designer lacks the ability to observe the individuals’ actual preferences. -

Workshop on Advancements in Social Choice

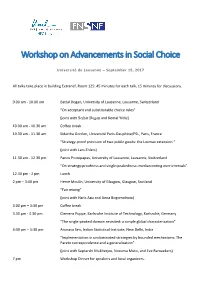

Workshop on Advancements in Social Choice Université de Lausanne – September 15, 2017 All talks take place in building Extranef, Room 125: 45 minutes for each talk, 15 minutes for discussions. 9.00 am ‐ 10.00 am Battal Dogan, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland “On acceptant and substitutable choice rules” (joint with Serhat Dogan and Kemal Yildiz) 10.00 am ‐ 10.30 am Coffee break 10.30 am ‐ 11.30 am Sidartha Gordon, Université Paris‐Dauphine/PSL, Paris, France “Strategy‐proof provision of two public goods: the Lexmax extension “ (joint with Lars Ehlers) 11.30 am ‐ 12.30 pm Panos Protopapas, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland “On strategy‐proofness and single‐peakedness: median‐voting over intervals” 12.30 pm ‐ 2 pm Lunch 2 pm – 3:00 pm Herve Moulin, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland “Fair mixing” (joint with Haris Aziz and Anna Bogomolnaia) 3.00 pm – 3:30 pm Coffee break 3.30 pm ‐ 4.30 pm Clemens Puppe, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany “The single‐peaked domain revisited: a simple global characterization” 4:30 pm – 5:30 pm Arunava Sen, Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi, India “Implementation in undominated strategies by bounded mechanisms: The Pareto correspondence and a generalization” (joint with Saptarshi Mukherjee, Nozomu Muto, and Eve Ramaekers) 7 pm Workshop Dinner for speakers and local organizers. Abstracts Battal Dogan, On acceptant and substitutable choice rules: Each acceptant and substitutable choice rule is known to have a collected maximal representation: there exists a list of priority orderings such that from each choice set that includes more elements than the capacity, the choice is the union of the priority orderings’ maximizers (Aizerman and Malishevski, 1981). -

Soumendu Sarkar

Soumendu Sarkar Affiliation Delhi School of Economics Cell: +919810423224 University of Delhi [email protected] New Delhi 110007 India Current Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, Delhi School of Economics, Position 2021-present Previous TERI School of Advanced Studies, New Delhi, Positions Assistant Professor, 2015-2021 Lecturer, 2011-2015 Education Indian Statistical Institute Delhi, New Delhi, India Ph.D., Quantitative Economics, 2015 • Thesis Title: Mechanism Design For Land Acquisition • Advisor: Professor Arunava Sen Visva Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal M.A., Economics, 2001 • First Class • Specialization: Money and Finance • Thesis Topic: Rationale and Importance of Federal Fiscal Transfers in India B.A., Economics, 1999 • First Class First • Minor in Mathematics Research Interests • Mechanism Design • Auction Theory • Social Choice • Game Theory Publications • Predatory Pricing and the Notion of Multi-Market Dominance: A Case of the In- dian Telecom Industry, in Business, Economics and Sustainable Development : The Emerging Horizons, edited by Manipadma Datta et al.(2020), Bloomsbury • Auctions, negotiation and winner's curse in coal mining in India, International Jour- nal of Management Practice, 2021, 14(1), 35-48 • Convergence of VCG mechanism to ex-post Budget Balance in a Model of Land Acquisition, Mathematical Social Sciences, 2018, 93, 37{46. • Mechanism Design for Land Acquisition, International Journal of Game Theory, 2017, 46(3), 783{812. Working Papers • Optimal Mechanism for Land Acquisition, -

Curriculum Vitae

January 2018 Curriculum Vitae Rajiv Vohra Ford Foundation Professor of Economics Brown University Providence, RI 02912 rajiv [email protected] http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Economics/Faculty/Rajiv Vohra Education Ph.D. (Economics), 1983, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. M.A. (Economics), 1981, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. M.A. (Economics), 1979, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, India. B.A. (Economics Hons.), 1977, St. Stephen's College, University of Delhi, India. Current Position Ford Foundation Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 2006 - Other Positions Dean of the Faculty, Brown University, July 2004 - June 2011. Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 1989 - June 2006. Morgenstern Visiting Professor of Economic Theory, New York University, Fall 2001. Fulbright Research Scholar, Indian Statistical Institute, 1995-1996. Chairman, Department of Economics, Brown University, July 1991 - June 1995. Visiting Fellow, Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi, August 1987 - July 1988. Associate Professor of Economics, Brown University, January 1987 - June 1989. Assistant Professor of Economics, Brown University, July 1983 - December 1986. 1 Professional Activities Co-Organizer, 2016, NSF-CEME Decentralization Conference, Brown Uni- versity. Organizer, Conference in Honor of M. Ali Khan, Johns Hopkins University, 2013. Associate Editor, International Journal of Game Theory, 2003 - 2009. Associate Editor, Journal of Mathematical Economics, 1994 - 2009. Associate Editor, Journal of -

Swaprava Nath: Curriculum Vitae

Swaprava Nath Computer Science and Engineering Voice: (+91) 512 679 2003 Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Office: KD 224 Kalyanpur, Kanpur 208 016 Email: [email protected] (preferred) U.P., India Homepage: www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/swaprava Research Interests Artificial intelligence, multi agent systems, game theory, mechanism design, computational social choice, crowdsourcing, social networks. Academic Employment • Assistant Professor 2017 - till date Department of Computer Science and Engineering Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, India • Fulbright-Nehru Post Doctoral Fellow 2015 - 2017 Computer Science Department Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA Host: Dr. Ariel Procaccia Research: Computational Social Choice • Lecturer and Post Doctoral Fellow 2013 - 2015 Economics and Planning Unit Indian Statistical Institute, New Delhi, India Host: Prof. Arunava Sen Research: Mechanism Design Theory Education • Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in Computer Science 2013 Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India Research: Mechanism Design for Strategic Crowdsourcing Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Y. Narahari • Master of Engineering (M.E.) in Telecommunication 2008 Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India Research: Self Organization in Wireless Sensor Networks Research Supervisor: Prof. Anurag Kumar • Bachelor of Engineering (B.E.) in Electronics & Telecommunication 2006 Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India Final year project: Analysis of Time Modulated Linear Antenna Array Project Supervisor: Prof. Bhaskar Gupta Awards and Achievements • Received Fulbright-Nehru Postdoctoral Fellowship for research in Internet Economics, 2015. • Received Honorable Mention Award in Yahoo! Key Scientific Challenges Program, 2012. • Received the Tata Consultancy Services PhD Fellowship for 2010. • Awarded Intern Day Prize for the presentation on Intern Day, August 30, 2010, at Xerox Research Centre Europe, Grenoble, France. -

Gopakumar Achuthankutty

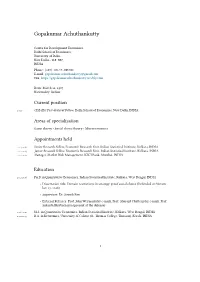

Gopakumar Achuthankutty Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, New Delhi - 110 007, INDIA Phone: (+91) 80-17-995108 E-mail: [email protected] url: https://gopakumarachuthankutty.weebly.com Born: March 11, 1987 Nationality: Indian Current position 2019- CDE-IEG Post-doctoral Fellow, Delhi School of Economics, New Delhi, INDIA Areas of specialization Game theory • Social choice theory • Microeconomics Appointments held 2014-2018 Senior Research Fellow, Economic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, INDIA 2012-2014 Junior Research Fellow, Economic Research Unit, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, INDIA 2010-2012 Manager, Market Risk Management, ICICI Bank, Mumbai, INDIA Education 2012-2018 Ph.D in Quantitative Economics, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA • Dissertation title: Domain restrictions in strategy-proof social choice (Defended on Novem- ber 27, 2018) • Supervisor: Dr. Souvik Roy • External Referees: Prof. John Weymark (by e-mail), Prof. Shurojit Chatterji (by e-mail), Prof. Sukanta Bhattacharya (present at the defense) 2008-2010 M.S. in Quantitative Economics, Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, West Bengal, INDIA 2004-2007 B.A. in Economics, University of Calicut (St. Thomas College, Thrissur), Kerala, INDIA 1 Grants, honors & awards 2019 CDE-IEG Post-doctoral Fellowship, Delhi School of Economics 2014 Senior Research Fellowship, Indian Statistical Institute 2012 Junior Research Fellowship, Indian Statistical Institute 2008 Student Fellowship, Indian Statistical Institute Publications Journal articles 2018 Achuthankutty, Gopakumar and Souvik Roy (2018), “On single-peaked domains and min-max rules”, Social Choice and Welfare, Volume 51, Issue 4, pp 753-772. Achuthankutty, Gopakumar and Souvik Roy (2018), “Dictatorship on top-circular domains”, Theory and Decision, Volume 85, Issue 3-4, pp 479-493. -

Intermediation in Network Economics: Theory and Applications

INTERMEDIATION IN NETWORK ECONOMICS: THEORY AND APPLICATIONS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MANOA¯ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ECONOMICS AUGUST, 2018 By Lining Han Dissertation Committee: Ruben Juarez, Chairperson Katya Sherstyuk Nori Tarui Sumner La Croix Qianqiu Liu, University Representative Keywords: Intermediation, Networks, Resource-Sharing, Financial Networks DEDICATION PAGE To my family, teachers and friends. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Looking back these years of life in Hawaii, the natural environment and people around are too nice to me. There are many things and many people to be thankful for during the past five years. First, my sincerest appreciation goes out to my adviser Ruben Juarez. Ruben enlightened me to think about topics in game theory and mechanism design. Without him, I could not imagine that I would be able to graduate with this dissertation and get a publication in Games and Economic Behavior. I never thought I would be able to solve some interesting problems. But little by little, I learned how to do research, present, and write papers from him. He had great patience to teach and help me in research. He spent much of his precious time giving me suggestions to revise the paper, how to write a research proposal and network with others. I was very lazy, depressed, and had serious procrastination issues, but he is a good example of hardworking and optimism which helped me to complete the program in 5 years. I also thank my committee members Katya Sherstyuk, Nori Tarui, Sumner La Croix and Qianqiu Liu. -

The Theory of Mechanism Design: an Overview

COMMENTARY voters are free to reveal any ranking, they The Theory of Mechanism can also misrepresent their true ranking. Clearly their report will depend on how Design: An Overview they believe others will vote. A natural question is whether a voting rule can be designed where voters can be induced to Arunava Sen reveal their true ranking irrespective of their beliefs regarding the voting behaviour Three USbased economists have he Nobel Prize in economics for of others. Unfortunately this does not hold been awarded the Nobel Prize 2007 was awarded to Leonid for either the Plurality Rule or rules based for economics for 2007 for laying THurwicz (University of Minnesota, on the Majority Principle. US), Eric Maskin (Institute of Advanced To see this consider (for simplicity) the the foundations of mechanism Studies, Princeton, US) and Roger Myerson case where there are are three voters 1, 2 design theory. A description (University of Chicago, US) for “having and 3 and exactly three proposals a, b and and discussion of this theory, laid the foundations of mechanism design c. Suppose that voter 1’s true ranking is a its importance and the work of theory”. What is this theory and why is it better than b better than c, 2’s true rank important? What are the contributions ing is b better than c better than a while 3’s the awardwinning economists. of the recipients of this year’s prize? true ranking is c better than a better than Mechanism design could help This article briefly attempts to address b.